Concerto for Florist & Ensemble (2009)

2009 version composed for James DelPrince, performance florist; Mark Applebaum & Tom Nunn, electroacoustic sound-sculptures & live electronics; Terry Longshore & Steve Schick, percussion; Brian McWhorter, trumpet; Jane Rigler, flutes; Scott Rosenberg, saxophones; Mark Dresser, contrabass. For a Stanford Lively Arts event at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center.

Concerto for Florist & Orchestra (2009)

For performance florist and large orchestra. Commissioned by the Fromm Foundation, Harvard University, for the La Jolla Symphony. Score and parts preparation funded by the 2010-2011 UCSD Thomas Nee Commission.

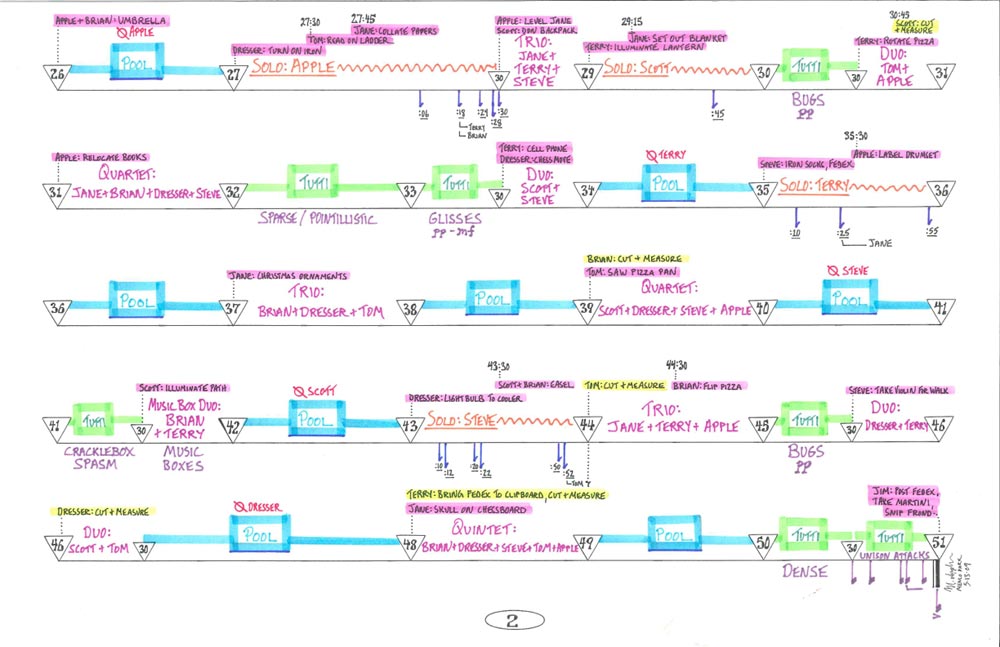

These are two separate but related pieces. By way of cursory differentiation, the ensemble piece involves a small instrumental cohort who improvise in response to a loose score and execute a bevy of strange, hilarious rituals during one long, continuous piece. By contrast, the orchestral version is scored determinately for a large group in three modest movements and absent of strange instrumentalist rituals. Videos from each performance appear below, as do their scores—including a document that details the rituals undertaken by the players in the ensemble version.

Here is a program note from the orchestral version that explains itself and references its ensemble ancestor:

I met James DelPrince, by chance, on an airplane in 1999. Four things happened during the ride, all in the span of about twenty seconds: I learned that he was a florist; I instantaneously had the idea of a concerto for florist; I asked him if he’d ever thought about being a performance florist; and he responded “Yes—I’ve always dreamed about being a performance florist.” The Concerto for Florist and Ensemble was premiered soon after, a piece for improvising musicians, with Jim simultaneously sculpting magnificent and idiosyncratic floral sculptures. The piece was revised for several subsequent performances, always with a new ensemble, a new improvisation score, and new durations. Likewise, Jim changed his approach to floristry each time, sometimes employing skewered green apples, barbed wire, or police crime scene tape, other times working with long-stemmed artichokes and a glue gun, inserting flowers and flashlights into salvaged car parts, or weaving fronds of juniper and tinsel. Jim is not your standard florist.

Steven Schick, conductor of the La Jolla Symphony Orchestra and a longtime friend, mentor, and collaborator, played percussion in the most recent adaptation of the Concerto for Florist and Ensemble, a 50-minute version scored for an octet of particular virtuoso musicians performed at the Cantor Arts Center Museum in 2009. Steve enthusiastically proposed a new piece for symphony orchestra, one that differs from its predecessors in a number of important ways. First, and most obvious, the Concerto for Florist and Orchestra has a generously expanded instrumentation, including six very active percussionists. Second, it is a three-movement work, whereas the earlier versions were all single movement forms. Third, and most significant, the musicians perform a determinate, traditionally notated composition, whereas earlier concerti featured improvisers who were directed when to play, but not what to play.

Unlike the orchestral players, the soloist is free to improvise his part spontaneously. Alternatively, he may choose to prepare an approximate agenda, or to formulate an exact series of step-by-step actions in advance. The only requirement is that his floral projects’ duration of execution matches those of the instrumentalists’ musical endeavors. In this regard, the spirit is very much akin to the classic Merce Cunningham and John Cage collaborations in which music and dance cohabitate rather than coordinate. My experiences composing for the Cunningham Company, first in 1993 and then in 2005, profoundly affected my aesthetic orientation. The music and dance—or music and floristry—will have coincidental, chance moments of seeming congruity, and other times of seemingly coordinated antithesis, both of which suggest a kind of cognitive clarity. But for me, the abundant time in which the media relate at an uncomfortable, oblique angle is of greatest interest and excitement. It is the problem of their incongruous juxtaposition that I find most arresting.

An alternative performer of another medium may be substituted. When such a substitution is made, the title is revised accordingly. Some examples include: Concerto for Juggler and Orchestra, Concerto for Plumber and Orchestra, Concerto for Contortionist and Orchestra, Concerto for Quilter and Orchestra, Concerto for Locksmith and Orchestra, Concerto for Chef and Orchestra, Concerto for Tax Attorney and Orchestra, etc. A Concerto for Composer and Orchestra might involve a composer (but not the one of this piece) quietly working at a desk onstage.

The Concerto for Florist and Orchestra was composed for the La Jolla Symphony Orchestra and was made possible by a grant from the Fromm Music Foundation. It is dedicated to Steven Schick and James DelPrince, intrepid collaborators, conspirators, and experimentalists.

By way of further explication, Jim Chute of the San Diego Union-Tribune asked me for a list of 10 Reasons to Write a Concerto for Florist and Orchestra. These are:

1. The joy of cohabitation. I was commissioned twice by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, in 1993 and 2005. Those experiences made a lasting impression on me. The working method of Cunningham and John Cage, which I adopted, was to first agree on a total duration. But the dancers would not hear Cage’s music and the musicians would not see Cunningham’s dance until the performance. As a consequence, moments of seemingly logical coherence would arise—by chance—between the dance and music. These moments include both congruence and polarity. But most of the time was spent in a cognitively problematic middle ground in which the two media relate at oblique angles. I find this middle ground intrinsically surreal and endlessly fascinating. (Others probably find it alienating.) As such, the florist in my concerto is free to pursue an artistic expression at the same time as the orchestra's discourse but independent of it. Cohabitation of floristry and sound—not coordination—is the rule.

2. The joy of failure. I'm not interested in being a “professional composer,” someone who is required to make safely understood and well-functioning work. I aspire to succeed (really I do!) but I'm prepared to fail. Do you remember those science “experiments” we used to do in high school? There was no experimentation involved, just recreations of known phenomena. I'm feeling most alive when I'm working at the margins of my knowledge and instinct.

3. The joy of mystery. The concept is a bit mysterious and inherently dissonant. It leaves unanswered questions and problems in its wake. Must we insist on a world in which everything is explained (the job of zealous religious leaders and patronizing politicians)?

4. The joy of voyeurism. I enjoy the role of the outsider, the voyeur of alien rituals—to watch people play games whose rules are unknown, to hear foreign languages, and to behold esoteric religious rites. I wonder what it will feel like to experience the odd concatenation of musical and floral endeavors.

5. Sound is not everything. Let’s use our eyes too. Earlier works of mine rely on what might be called sensory collisions: Tlön for three conductors and no players; the Mouseketier—made of junk, found objects, and hardware, and intended equally as musical instrument and sculpture; Straitjacket in which five players draw noisily on amplified easels in exact rhythmic unison but produce distinct pictures; and Aphasia for hand gestures performed in unison with an audio recording of mutated vocal samples. So too, the Concerto for Florist has a decidedly visual component. In fact, you can cover your ears and just watch Jim at work. To some extent one could do this with film, ballet, and other musical enterprises that partner with ocular experience. Scriabin’s Prometheus is essentially a concerto that stars its piano soloist as musical hero. But Scriabin, who was synesthetic, composed a part for “color organ” whose lights occasionally upstage the music.

6. Sound is everything. You can ignore the florist if you want. The concerto aspires to be an exciting and arresting piece of music in itself. There are musical fragments that bounce mercurially from player to player; an inexorably thumping passacaglia; a tangled mass of micropolyphonic glissandi; and six insanely active percussionists. The piece, as a sound object, is “artistically saturated.” One might argue that the puissant floristry histrionics detract from the complex musical discourse. Ah well, I guess I suffer from “if some is good, a lot must be great.”

7. Everything is music. The great thing about being a composer is that you can design projects that engender forays into other disciplines. When asked for a piece by new music ensemble Zeitgeist I composed a work about Louis Sullivan that invited a preliminary year of architecture studies. When the Vienna Modern Festival commissioned Asylum, in which psychological disorders are articulated in sound, I first read the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders from cover to cover. Thanks to working with Jim I now have new insights about floristry.

8. The greatest and worst concerto for florist and orchestra are one and the same piece. Sandwiched [in this concert] between Prokofiev and Bartok, how does a living composer attempt to get some elbow room? Expressed bleakly: maybe all the good concerti have already been written. So why compete (poorly) with the legacy of these great works? Perhaps as a consequence of mental defect or simply bad taste, I arrive at a piece that stands alone in its class by asking "What contribution am I uniquely inclined to make as a composer?"

9. Conductor courage. Some musicians tell me “This is what I do, please write me more of that.” Especially intrepid musicians tell me “This is what I do; please give me something different to do.” Steven Schick is decidedly in the latter category. My piece is a response to his open-mindedness, courage, willingness to try something different, and endless spirit of exploration.

10. Life is boring. Why not?

Experimental | Why Experimental?

Experimental | Why Experimental?

Download ensemble score (PDF- 804KB)

Download ensemble rituals (PDF- 88KB)

Download orchestral score (PDF- 1MB)