Procedural Recursion

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2022, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Slide 2

Announcements

- Assignment 3 is due Friday

- Note: the assignment is actually due Friday. Everyone has an automatic extension until Saturday, though if you turn it in then you won't get the on-time bonus. What this means is that if you ask for an extension, you've already got a 1-day extension. So, don't be too surprised if Neel and I don't give you more time.

High Resolution Course Evaluation

- We are always trying to make CS106B better. One of the ways we are attempting to do that is through a High Resolution Course Evaluation system, where every student will get two emails throughout the quarter asking for feedback on the course.

- We always appreciate constructive feedback, and we read all feedback!

- This week's notable feedback:

- "I am a little confused on how assignments are graded." and "I'm still a little confused about the style the course is looking for."

- Hopefully the grade for your first assignment made sense – please ask your SL during an IG to ellaborate on either grading or style.

- "The assignment instructions are really vague at some points and make it extremely unclear"

- Please ask for clarification on Ed, and let us know what you think is unclear

- "I still don't fully understand reference variables, or how/when/why we would use them in practice."

- This does take practice. There are lots of section examples to look at with references.

- "The assignments are too long to read." and "The pace of 106B is certainly much swifter than CS106A" and "I just didn't expect Assignment 1 to be this much work. It is definitely much more than the amount of work in CS 106A."

- Yes, this class is more challenging than CS106A. But, you are prepared for it! You do need to set aside enough time.

- "Yes, I am confused about how to determine which data structure to use for a given problem."

- Practice and seeing lots of examples (e.g., section problems) helps immensely.

- "Is it possible to have annotated versions of the lecture slides?"

- I'm not sure what this means. If you want to clarify what you mean, post on Ed or email me directly.

- "Is there any way for more resources to be posted on canvas? Having to use ed and the cs106b website can get complicated since canvas is used for every other class."

- No, we're keeping everyting on the website.

- "I think it would be advantageous to have the YEAH assignment video done on Friday when the assignment is released. Waiting until Monday evening to start a assignment is not something I can afford to do."

- You shouldn't be waiting until Monday to start it. You can always read the assignment, start thinking it through, and coming up with ideas before YEAH hours.

- "I would appreciate if more code from the in-class examples was included in the lecture notes."

- Every lecture has an associated Qt Creator project or projects with the code covered in lecture.

- "I am a little confused on how assignments are graded." and "I'm still a little confused about the style the course is looking for."

Slide 3

Today's Goals:

- Today and next time, we want to discuss how to use recursion to perform an exhaustive exploration of a search space.

- The examples we will cover:

- generating sequences from a set of choices

- generating all permutations

- generating all subsets

Slide 4

Why recursion?

- So far, you might be thinking to yourself: why do I need recursion, when I can solve lots of problems using simple loops?

-

Example: A factorial is a recursively defined number:

n! = n * (n-1)!, where1! = 1.4! = 4 * 3! = 4 * 3 * 2! = 4 * 3 * 2 * 1! = 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 24 - Let's write the factorial function recursively:

long factorial(long n) { // base case if (n == 1) { return 1; } // recursive case return n * factorial(n-1); } - But wait…we could have just written this iteratively, using a loop!

long factorial(long n) { long answer = 1; while (n > 1) { answer *= n; n--; } return answer; } - These relatively easy recursive problems may have beautiful solutions, but there isn't anything special about solving the problem recursively.

- Today, we will discuss problems that deal with "iterative branching" – and it is these problems that demonstrate the power of a recursive solution.

Slide 5

Templates for recursive functions

- There are basically five different problems you might see that will require the kind of recursion we are transitioning to:

- Determine whether a solution exists

- Find a solution

- Find the best solution

- Count the number of solutions

- Print/find all the solutions

- We are going to focus today on the last item, printing and finding all solutions.

Slide 6

Generating sequences

Let's say you flip a coin twice. What are the possible sequences that might result? A little human brainstorming can come up with the four possibilities:

H H

H T

T H

T T

What about a sequence of three coin flips or four? If we try to manually enumerate these longer sequences, how can we be sure we got them all and didn't repeat any? It will help to take a systematic approach.

Consider: how does a length N sequence build upon the length N-1 sequences? If we take each of the above length 2 sequences and paste an H or T on the front, we will generate all the length 3 sequences. We can do something similar to extend from length 3 to length 4 and so on. This indicates a self-similarity in the problem that should lend itself nicely to being solved recursively.

H H H

H H T

H T H

H T T

T H H

T H T

T T H

T T T

Slide 7

Decision trees

Let's create a visualization of the search space for coin flips. We model the choices and where each leads using a diagram called a decision tree.

Each decision is one flip, and the possibilities are heads or tails. A sequence of N flips has N such choices.

The top of the tree is the first choice with its possibilities underneath:

|

+--------+--------+

| |

H T

Each choice we make leads to a different part of the search space. From there, we consider the remaining choices. Below is a decision tree for the first two flips:

|

+--------+---------+

| |

H T

| |

+------+------+ +-----+------+

| | | |

HH HT TH TT

The height of the tree corresponds to the number of decisions we have to make. The width at each decision point corresponds to the number of options. To exhaustively explore the entire search space, we must try every possible option for every possible decision. That can be a lot of paths to walk!

Next let's write a function to generate these sequences. This code traverses the entire decision tree. By using recursion, we are able to capitalize on the self-similar structure.

void generateSequences(int length, string soFar)

{

if (length == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

} else {

generateSequences(length - 1, soFar + " H");

generateSequences(length - 1, soFar + " T");

}

}

Note that the recursive case makes two recursive calls. The first call recursively explores the left arm of the decision tree (having chosen "H"), the second explores the right arm (having chosen "T").

This function prints all possible 2^N sequences. If you extend the sequence length from N to N + 1, there are now twice as many sequences printed. It first prints the complete set of the sequences of length N each with an "H" pasted in front, followed by a repeat of the sequences of length N now with an "T" pasted in front.

Next we changed the search space. In place of flipping a coin, we will choose letter from the alphabet. The code changes only slightly (though it is ugly!):

void generateLetterSequencesUgly(int length, string soFar)

{

if (length == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

} else {

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'A');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'B');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'C');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'D');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'E');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'F');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'G');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'H');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'I');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'J');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'K');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'L');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'M');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'N');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'O');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'P');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'Q');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'R');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'S');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'T');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'U');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'V');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'W');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'X');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'Y');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'Z');

}

}

Can we fix this code so that it isn't so tedious? This is a CS 106A question! A loop is just the thing to compactly express iterating over the alphabet:

void generateLetterSequencesNice(int length, string soFar)

{

if (length == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

} else {

for (char ch = 'A'; ch <= 'Z'; ch++) {

generateLetterSequencesNice(length - 1, soFar + ch);

}

}

}

Using both iteration and recursion in combo may be a bit puzzling. In some of our previous examples, recursion was used as an alternative to iteration, but in this case, both are working together. The iteration is used to enumerate the options for a given single choice. Once an option is picked in the loop, recursion is used to explore subsequent choices from there. In terms of the decision tree, iteration is traversing horizontally and recursion is traversing vertically.

Slide 8

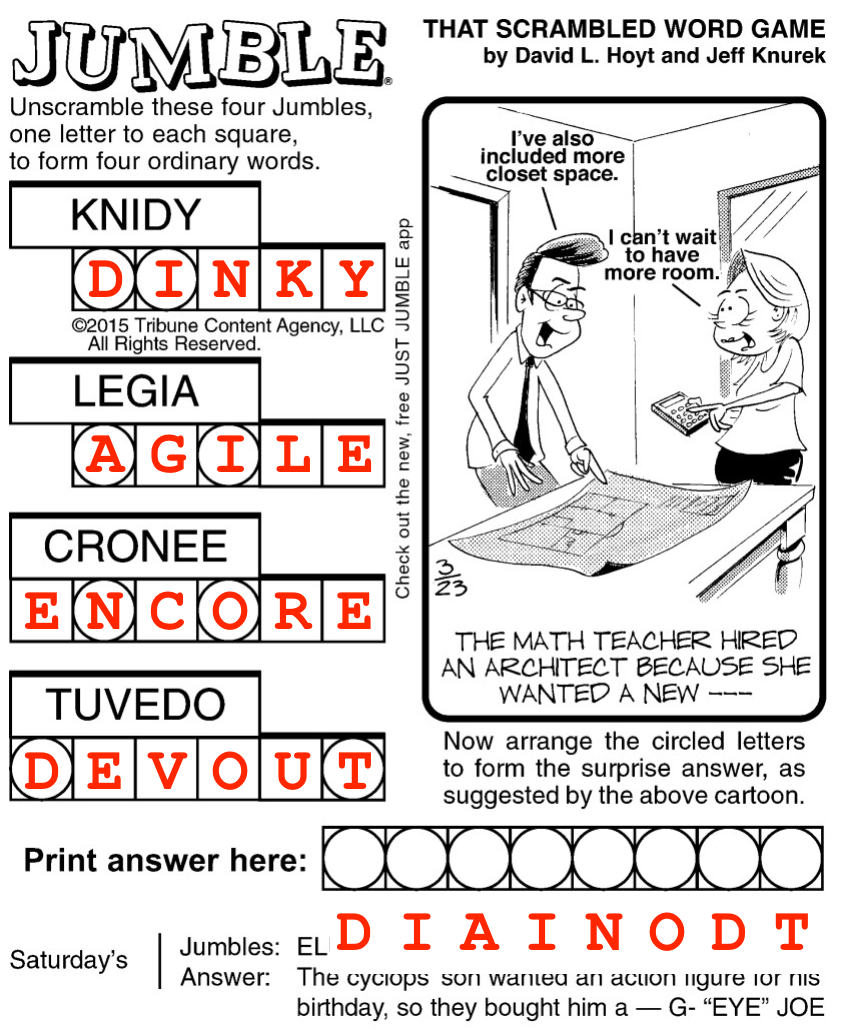

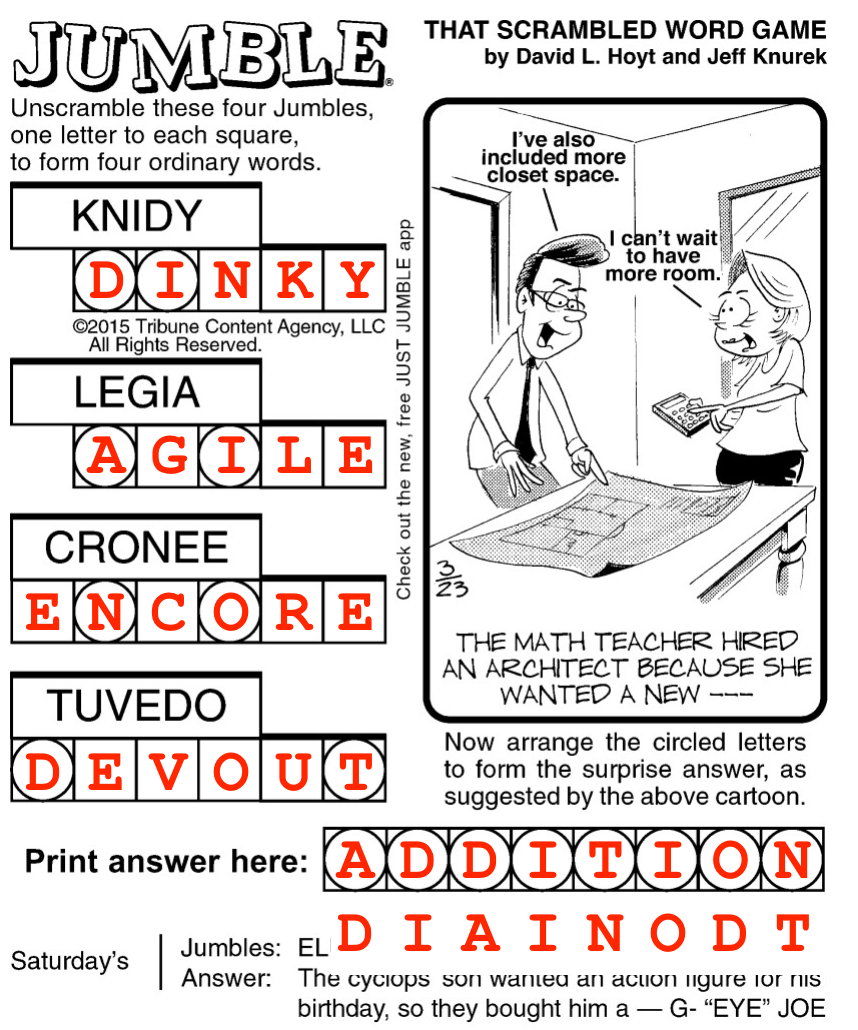

Jumble

- Since 1954, the JUMBLE has been a staple in newspapers.

- The basic idea is to unscramble the anagrams for the words on the left, and then use the letters in the circles as another anagram to unscramble to answer the pun in the comic.

- As a kid, I played the puzzle every day, but some days I just couldn't descramble the words. Six letter words have 6! == 720 combinations, which can be tricky!

-

I figured I would write a computer program to print out all the permutations!

- Partial solution (words on left descrambled):

- Full solution:

Slide 9

Permutations – the wrong way

- My original function to print out the permutations of four letters:

void permute4(string s) { for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < 4 ; j++) { if (j == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) { if (k == j || k == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int w = 0; w < 4; w++) { if (w == k || w == j || w == i) { continue; // ignore } cout << s[i] << s[j] << s[k] << s[w] << endl; } } } } } - I also had a

permute5()function:void permute5(string s) { for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < 5 ; j++) { if (j == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { if (k == j || k == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int w = 0; w < 5; w++) { if (w == k || w == j || w == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int x = 0; x < 5; x++) { if (x == k || x == j || x == i || x == w) { continue; } cout << " " << s[i] << s[j] << s[k] << s[w] << s[x] << endl; } } } } } }

- And I had a

permute6()function…void permute6(string s) { for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < 5 ; j++) { if (j == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { if (k == j || k == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int w = 0; w < 5; w++) { if (w == k || w == j || w == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int x = 0; x < 5; x++) { if (x == k || x == j || x == i || x == w) { continue; } for (int y = 0; y < 6; y++) { if (y == k || y == j || y == i || y == w || y == x) { continue; } cout << " " << s[i] << s[j] << s[k] << s[w] << s[x] << s[y] << endl; } } } } } } }

- This is not tenable!

- In the Linux kernel coding style guide (mostly written by Linus Torvalds, himself), indentations are 8 spaces, which is a lot. This is what the guide says:

Now, some people will claim that having 8-character indentations makes the code move too far to the right, and makes it hard to read on a 80-character terminal screen. The answer to that is that if you need more than 3 levels of indentation, you’re screwed anyway, and should fix your program. [source]

- We can take this to heart and say that our permutation-by-looping methods above are not a good idea.

Slide 10

Permutations: the correct way

- Permutations do not lend themselves well to iterative looping because we are really rearranging the letters, which doesn't follow an iterative pattern.

- Instead, we can look at a recursive method to do the rearranging, called an exhaustive algorithm. We want to investigate all possible solutions. We don't need to know how many letters there are in advance!

-

In pseudocode:

If you have no more characters left to rearrange, print current permutation

for (every possible choice among the characters left to rearrange) {

Make a choice and add that character to the permutation so far

Use recursion to rearrange the remaining letters

} - In English:

- The permutation starts with zero characters, as we have all the letters in the original string to arrange. The base case is that there are no more letters to arrange.

- Take one letter from the letters left, add it to the current permutation, and recursively continue the process, decreasing the characters left by one.

- In C++:

void permute(string soFar, string rest) { if (rest == "") { cout << soFar << endl; } else { for (int i = 0; i < rest.length(); i++) { // remove character we are on from rest string remaining = rest.substr(0, i) + rest.substr(i+1); permute(soFar + rest[i], remaining); } } } - Example call:

permute("", "abcd");

- Output:

abcd abdc acbd acdb adbc adcb bacd badc bcad bcda bdac bdca cabd cadb cbad cbda cdab cdba dabc dacb dbac dbca dcab dcba

Slide 11

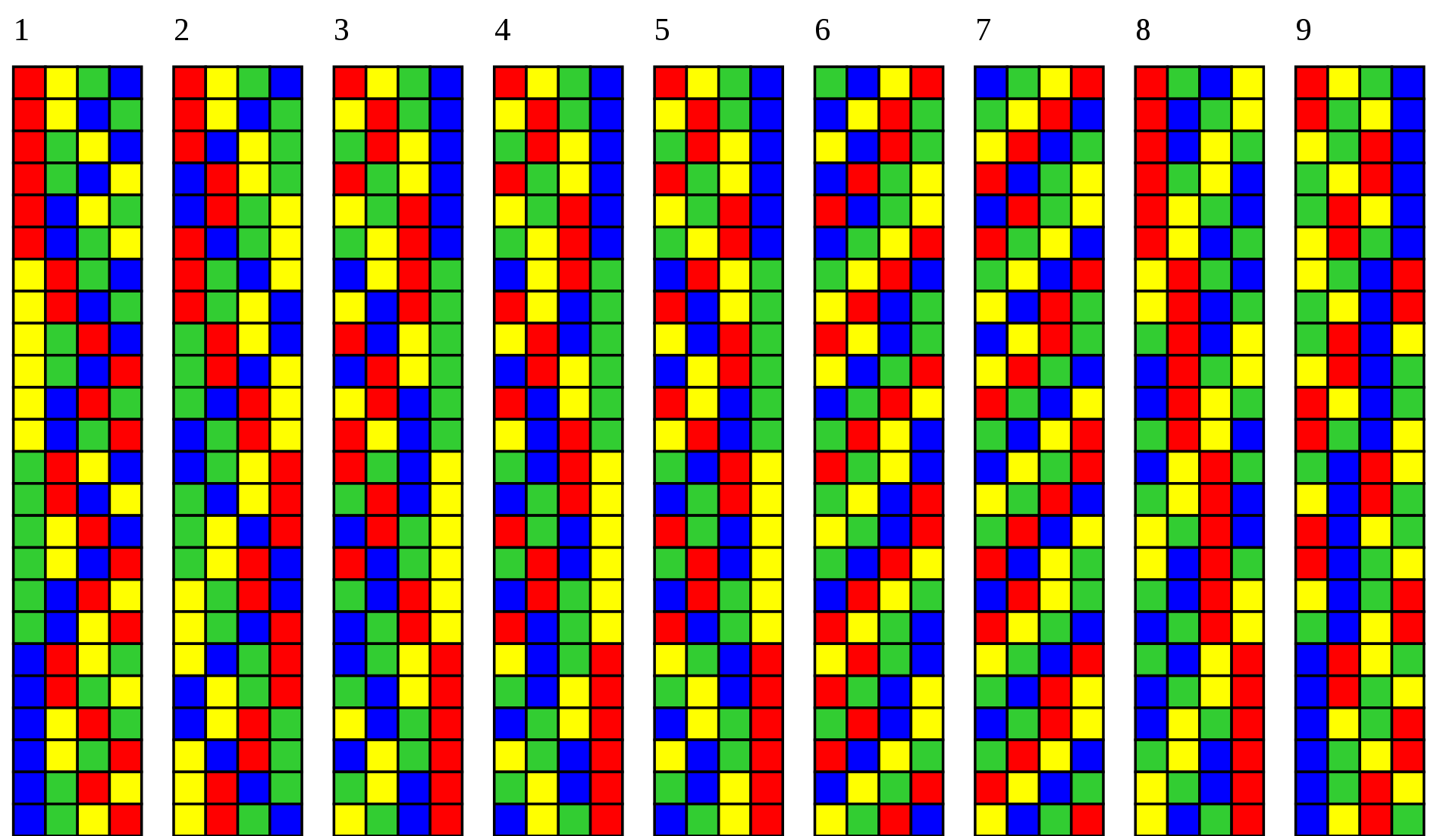

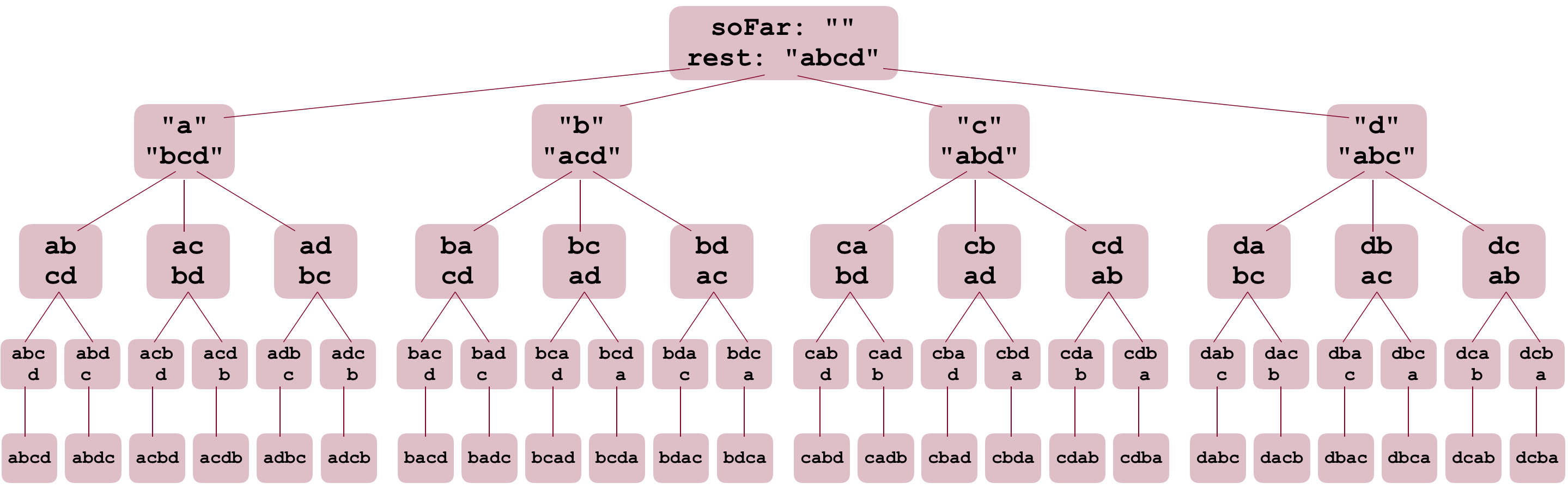

The search tree

- This is a permutation tree, which is very similar to the decision tree: it is an upside down tree, actually, with the root at the top of the diagram, and the leaves at the bottom. At each stage, the tree branches to form more parts of the permutation.

- In the first iteration of the function,

soFarfirst becomesa, andrestbecomesbcd. Likewise for the second iteration:soFarbecomesbandrestbecomesacd. - If we follow the left branch all the way down, you can see that

soFarkeeps getting updated, andrestgets smaller. In fact, you should notice in the last row that the order of the output we got on the last slide was the same as this diagram – this happens because the first call topermutekeeps recursing all the way toabcd, and then the prior branch (ab,cd) also has to branch toabd,candabdcbefore returning up toaandbcd. Doing this tracing on the diagram can be super important to understanding how the recursion is progressing.

Slide 12

Helper functions for recursive functions

- Here is the

permutecode again:void permute(string soFar, string rest) { if (rest == "") { cout << soFar << endl; } else { for (int i = 0; i < rest.length(); i++) { string remaining = rest.substr(0, i) + rest.substr(i+1); permute(soFar + rest[i], remaining); } } } - Some might argue that this isn't a particularly good function, because it requires the user to always start the algorithm with the empty string for the

soFarparameter. It's ugly, and it exposes our internal parameter. - What we really want is a

permute(string s)function that is cleaner. - In C++, we can overload the

permute()function with one parameter and have a cleaner permute function that calls the original one with two parameters:void permute(string s) { permute("", s); } - Note that this function has the same name as the original – this is legal in C++ as long as the compiler can differentiate the two by their (different) parameters.

- Now, a user only has to call

permute("tuvedo"), which hides the recursion parameter.

Slide 13

More Decision Trees

- Sometimes with recursion, we want to find out if there we can find a solution among all of the possibilities, but we can stop a particular path once we realize it isn't going to produce a solution. Let's look at an example:

- Here is a word puzzle: "Is there a nine-letter English word that can be reduced to a single-letter word one letter at at time by removing letters, leaving a legal word at each step?" We can call such a word a reducable word.

- 4 letter example:

cart -> art -> at -> a

- Can you think of a 9-letter word?

- 4 letter example:

startling -> starling -> staring -> string -> sting -> sing -> sin -> in -> i

- Is there really just one nine-letter word with this property?

- Could we do this iteratively? Possibly, but it would be messy!

- Can we do this recursively? Yes, with a decision tree!

- Notice that we can find a path through the tree in two different ways:

Slide 14

Decision tree search template

bool search(currentState) {

if (no more moves possible from currentState) {

return isSolution(currentState);

} else {

for (option : moves from currentState) {

nextState = takeOption(curr, option);

if (search(nextState)) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

}

Slide 15

Reducible word

-

Let's define a reducible word as a word that can be reduced down to one letter by removing one character at a time, leaving a word at each step.

- Base case:

- A one letter word in the dictionary.

- Recursive Step:

- Any multi-letter word is reducible if you can remove a letter (legal move) to form a shrinkable word.

- Let's code!

Slide 16

Reducible code

bool reducible(Lexicon & lex, string word) {

// base case

if(word.length() == 1 && lex.contains(word)) {

return true;

}

// recursive case

for(int i = 0; i < (int)word.length(); i++) {

string copy = word;

copy.erase(i, 1);

if(lex.contains(copy)) {

if(reducible(lex, copy)) {

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}