Trees

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2022, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Slide 2

Announcements

- Assignment 6 has been released

Slide 3

Today's Topics

- Refresh on what pointer diagrams represent

- Quick comment on references to pointers

- Introduction to the tree data structure

- You've already seen lots of tree structures

- Tree terminology

- How do we build trees programatically?

- Writing code to traverse a tree

Slide 4

Pointer Diagram Refresh

- The following diagram was put together by a former CS106B student:

- Pointers have values that are memory addresses.

- All variables and objects have their own memory address where they are located

- The

nextpointer is a memory address

Slide 5

A note on references to pointers

- In assignment 6, you have to write the following two functions:

void runSort(ListNode*& front) { /* TODO: Implement this function. */ } void quickSort(ListNode*& front) { /* TODO: Implement this function. */ } - Notice that each function is passed in a reference to a pointer (and Question 7 on that part of the assignment asks about this). The reference is necessary. If the parameter was not a reference, then the pointer would be passed by value, and any changes to the pointer would not be reflected in the code that called the function. Instead, the function would have to return the pointer so it could be updated in the calling function. But, it is cleaner to call the functions so they actually change the front of the list to be the first sorted element.

- In our example from the last lecture, we didn't need to worry about this, because all of our class functions had direct access to the

frontclass variable. This isn't the case when we don't have a class (as in the assignment). - See the code below that demonstrates why you need a reference to a pointer:

#include <iostream> #include "console.h" using namespace std; struct ListNode { string data; ListNode *next; }; void insertAtFrontIncorrect(ListNode* front, string s) { ListNode *newNode = new ListNode; newNode->data = s; newNode->next = front; front = newNode; } void insertAtFrontCorrect(ListNode*& front, string s) { ListNode *newNode = new ListNode; newNode->data = s; newNode->next = front; front = newNode; } void printListIncorrect(ListNode*& front) { cout << "["; while (front != nullptr) { cout << front->data; if (front->next != nullptr) { cout << ", "; } front = front->next; } cout << "]" << endl; } void printListCorrect(ListNode* front) { cout << "["; while (front != nullptr) { cout << front->data; if (front->next != nullptr) { cout << ", "; } front = front->next; } cout << "]" << endl; } int main() { ListNode *front = nullptr; cout << "inserting cat correctly" << endl; insertAtFrontCorrect(front, "cat"); cout << "inserting dog incorrectly" << endl; insertAtFrontIncorrect(front, "dog"); cout << "inserting bat correctly" << endl; insertAtFrontCorrect(front, "bat"); cout << "inserting rat correctly" << endl; insertAtFrontCorrect(front, "rat"); cout << "printing correctly:" << endl; printListCorrect(front); cout << "printing incorrectly:" << endl; printListIncorrect(front); cout << "printing correctly:" << endl; printListCorrect(front); return 0; }Output:

inserting cat correctly inserting dog incorrectly inserting bat correctly inserting rat correctly printing correctly: [rat, bat, cat] printing incorrectly: [rat, bat, cat] printing correctly: []

Slide 6

Trees

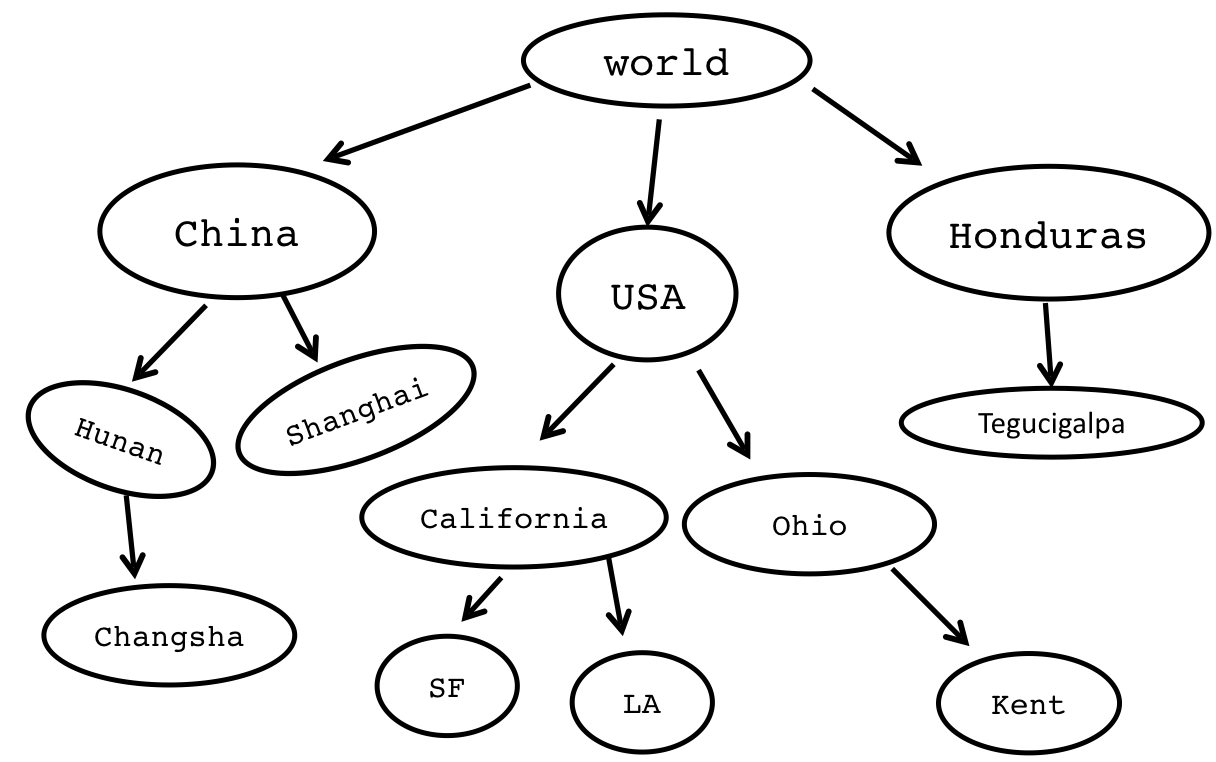

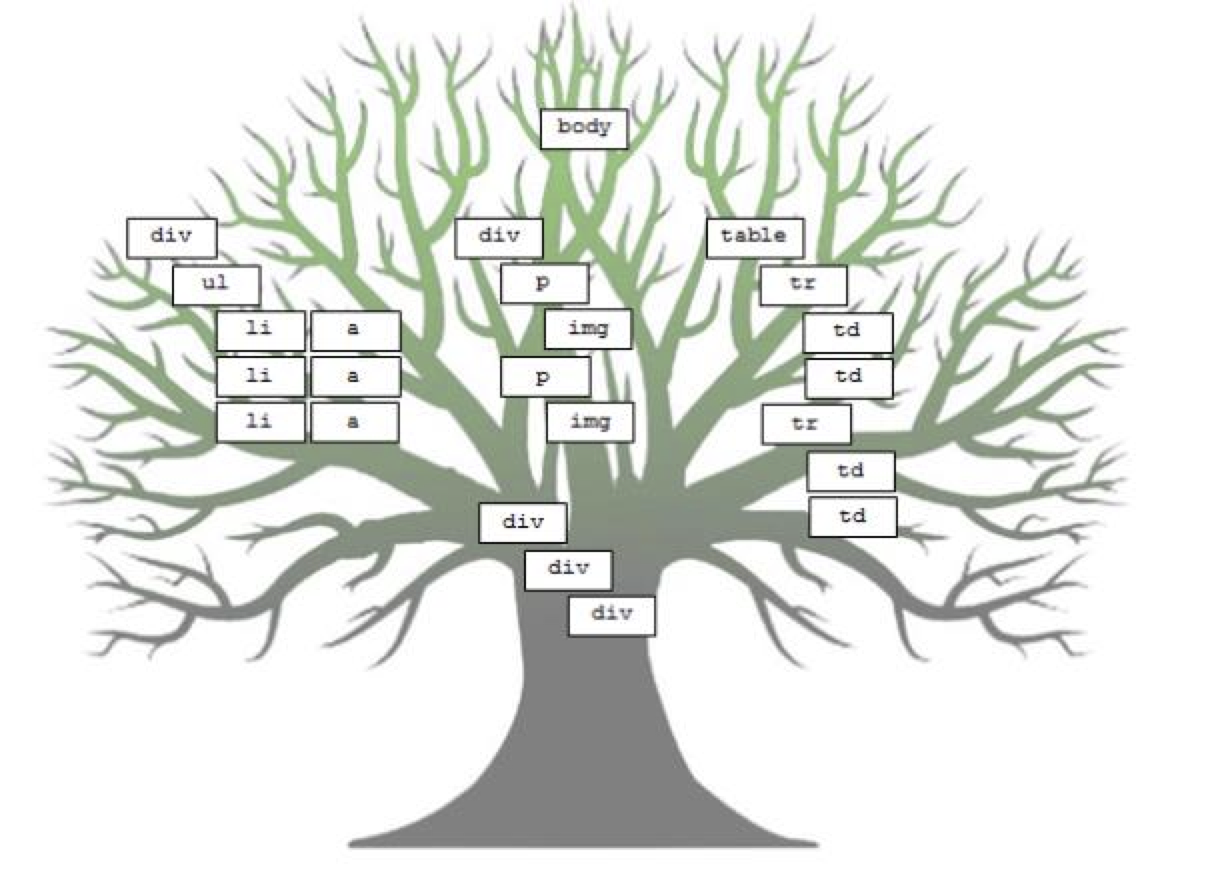

- We have seen trees in this class before, in the form of decision trees:

- Trees can describe hirearchies:

- Trees can describe websites:

- Trees can desceribe programs (we often call them abstract syntax trees (the following is a figure in an academic paper written by a recent CS 106 student!)

// Example student solution function run() { // move then loop move(); // the condition is fixed while (notFinished()) { if (isPathClear()) { move(); } else { turnLeft(); } // redundant move(); } }

Slide 7

Trees are inherently recursive

- What is a tree in computer science?

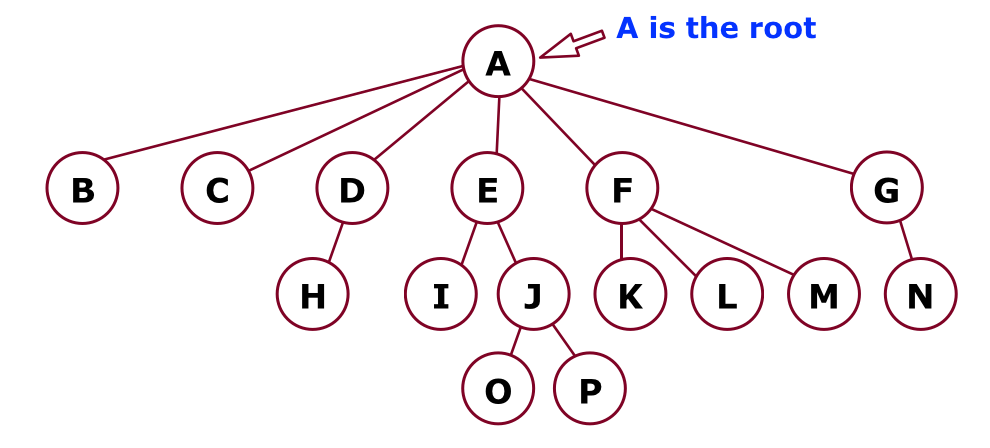

- A tree is a collection of nodes, which can be empty. If it is not empty, there is a root node,

r, and zero or more non-empty subtrees,T1,T2, …,Tk, whose roots are connected by a directed edge fromr.

- A tree is a collection of nodes, which can be empty. If it is not empty, there is a root node,

(root)

-----------A--------------

↙︎ ↙︎ ↙︎ ↓ ↘︎ ↘︎

B C D E F-- G

↙︎ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ ↘︎

H I J K L M N

↙︎ ↘︎

O P

- There are N nodes and N-1 edges in a tree.

- Tree terminology. In the diagram above:

- B is a child of A, and F is a child of A and a parent of K, L, M.

- Nodes with no children are leaves. Nodes B, C, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, and P are all leaves.

- Nodes with the same parent are siblings. I and J are siblings. K, L, and M are siblings. Nodes O and P are siblings. Nodes H and N do not have any siblings (only children).

Slide 8

More Tree Terminology

(root)

A--------------

↓ ↘︎ ↘︎

E F G

↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ ↘︎

I J K L M N

↙︎ ↘︎

O P

- We can define a path from a parent to its children. The path from A to O is: A-E-J-O.

- The path A-E-J-O has a length of three (the number of edges).

- The depth of a node is the length from the root. The depth of node J is 2. The depth of the root is 0.

- The height of a node is the longest path from the node to a leaf. The height of node F is 1. The height of all leaves is 0.

- The height of a tree is the height of the root. The height of the above tree is 3.

Slide 9

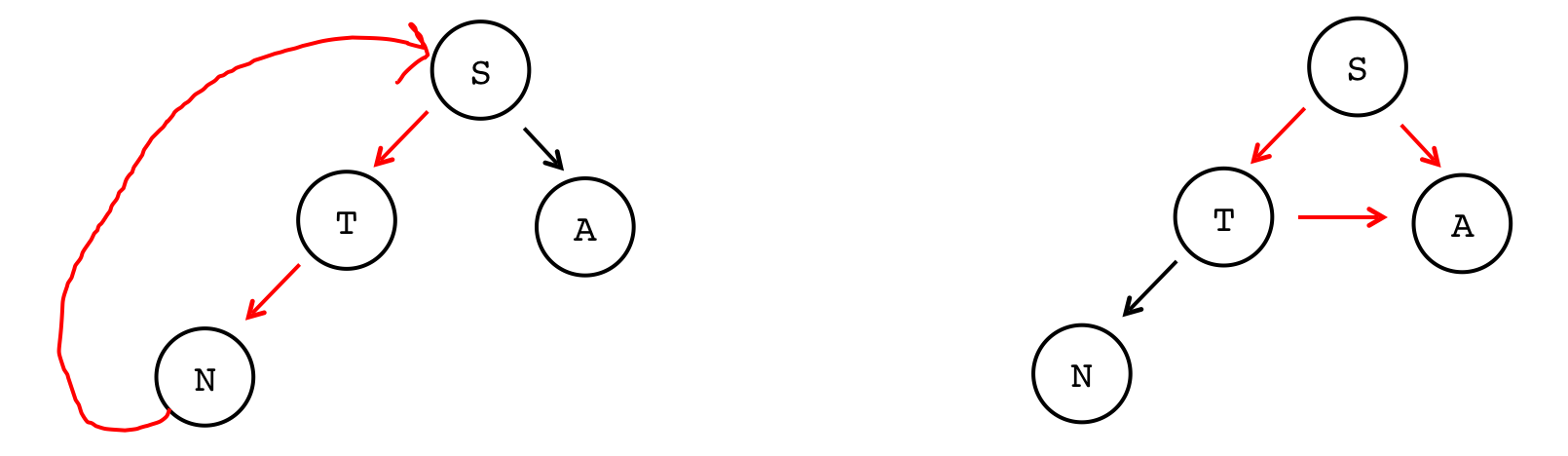

One Parent, No Cycles

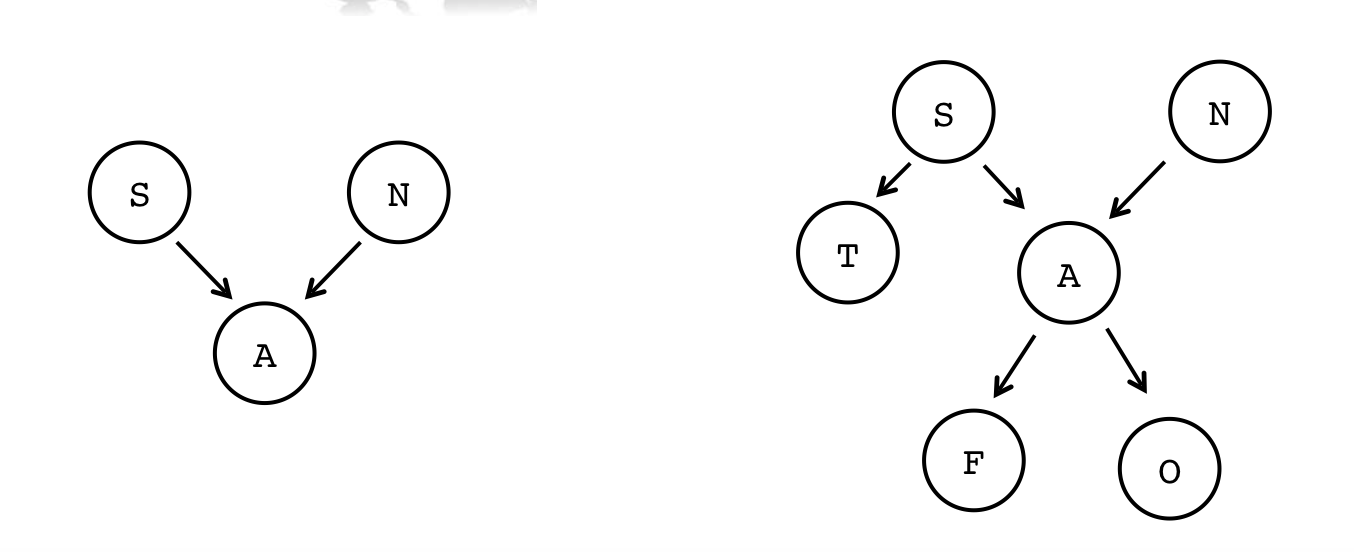

- Tree nodes can only have one parent, and they cannot have cycles

- Not a tree (A has two parents):

S N ↘︎ ↙︎ A - Again: not a tree (A has two parents):

S N ↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ T A ↙︎↘︎ F O - The following are not trees, either, because you can cycle through the tree. Nodes cannot have children that are on the same level or above on the tree:

- Not a tree (cycle from N back to S):

→→→→S ↑ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↑ T A ↑↙︎ N - Again: not a tree (the arrow from T to A causes a cycle):

S ↙︎ ↘︎ T→→→A ↙︎ N

Slide 10

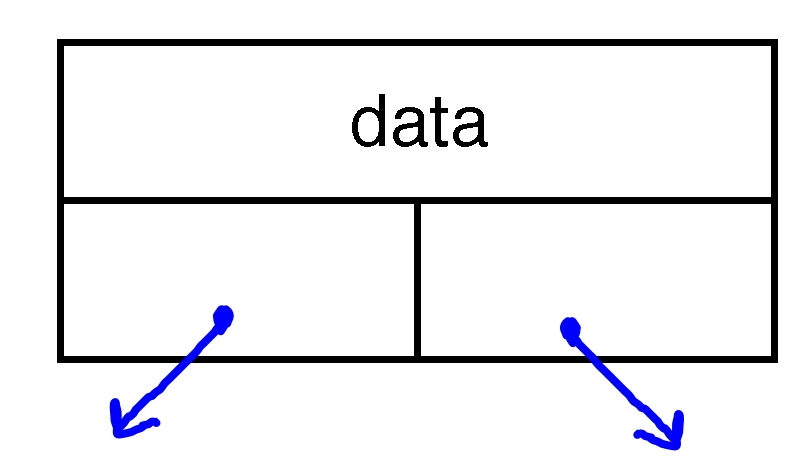

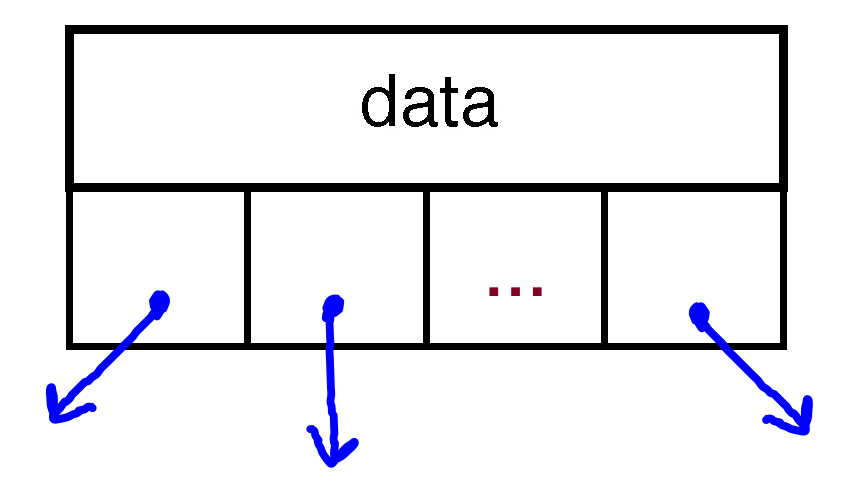

Building trees programatically

- To build a tree, we need a new version of our

Node. In this case, we want eachNodeto have a data value (like a linked list), but now we want to pointers, one to the left child, and one to the right child:struct TreeNode { string data; TreeNode* left; TreeNode* right; };

- We don't have to limit ourselves to binary trees, by the way: we could have a ternary tree:

struct TernaryTreeNode { string data; TernaryTreeNode* left; TernaryTreeNode* middle; TernaryTreeNode* right; };

- In fact, we could have any number of children (we may look at the Trie data structure, which can be built this way). This is an N-ary Tree:

struct NAryTreeNode { string data; Vector<NAryTreeNode*> children; };

Slide 11

Traversing a Tree

- Often, we will want to do something with each node in a tree. Like linked lists, we can traverse the tree, but it is more involved because of all the branching.

- There are four different ways to traverse a binary tree:

- Pre-order

- In-order

- Post-order

- Level-order

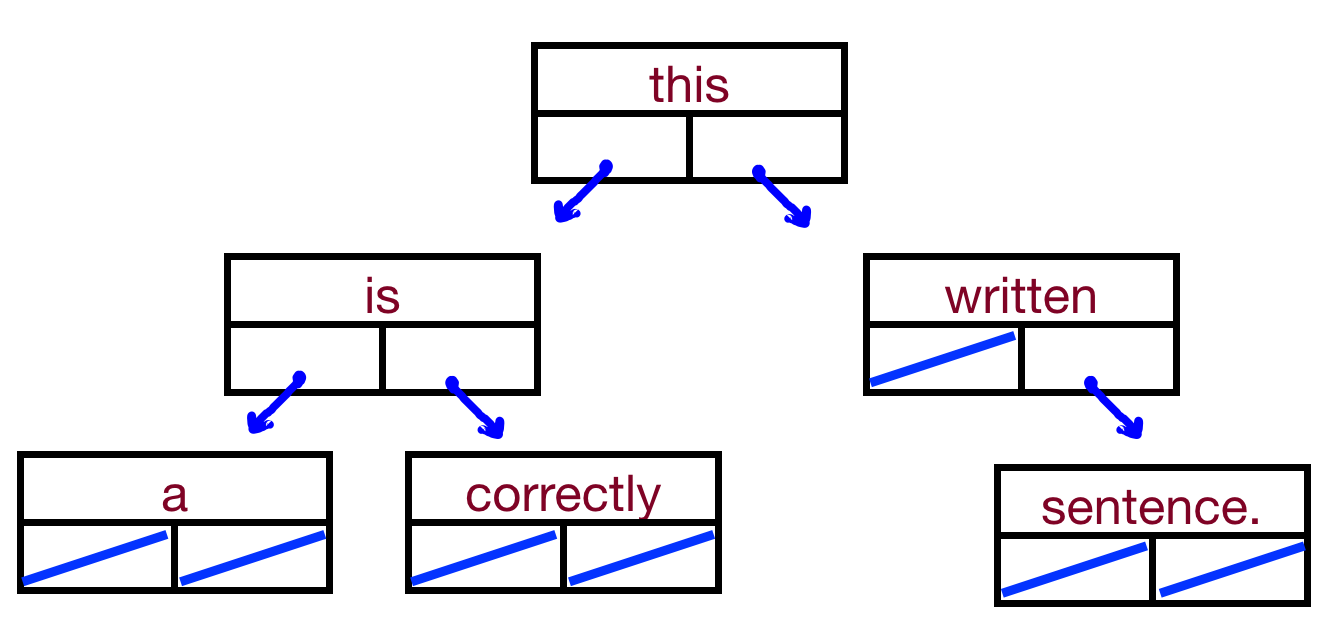

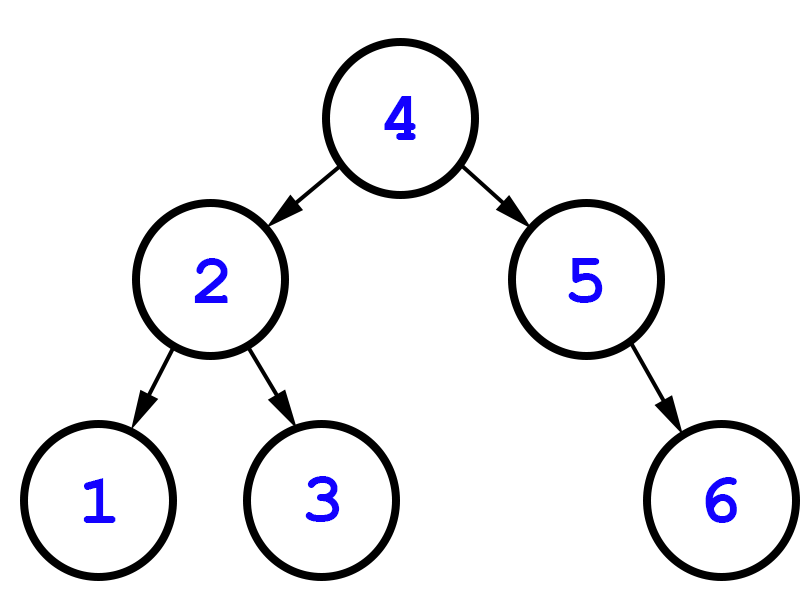

- Let's write some code for each traversal to see the differences. We'll look at two trees:

this ↙︎ ↘︎ is written ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ a correctly sentence - We'll also look at:

4 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 5 ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ 1 3 6 - By the way: trees do not have to be complete, like heaps. Any node can have 0, 1, or 2 children.

Slide 12

Pre-order traversal

- The algorithm for a pre-order traversal is as follows:

- Do something

- Go left

- Go right

- This is an inherently recursive algorithm

- For our tests, let's make the "Do something" part print the data at a particular node.

- Code:

void preOrder(TreeNode* tree) { if(tree == nullptr) return; cout<< tree->data <<" "; preOrder(tree->left); preOrder(tree->right); }

Slide 13

In-order traversal

- The algorithm for a in-order traversal is as follows:

- Go left

- Do something

- Go right

- This is also an inherently recursive algorithm

- Code:

void inOrder(TreeNode* tree) { if(tree == nullptr) return; inOrder(tree->left); cout<< tree->data <<" "; inOrder(tree->right); }

Slide 14

Post-order traversal

- The algorithm for a post-order traversal is as follows:

- Go left

- Go right

- Do something

- This is also an inherently recursive algorithm

- Code:

void postOrder(TreeNode* tree) { if(tree == nullptr) return; postOrder(tree->left); postOrder(tree->right); cout<< tree->data <<" "; }

Slide 15

Level-order traversal

- A level order traversal is different than all the others – we want to go one level at a time and print out each node, then go to the next level.

- For this tree, it would be:

this is written a correctly sentence

- Can we do this recursively!

- But, we can use an algorithm you've seen before: breadth first search!

- This is going to use a queue, just like the BFS you did for your maze solving assignment.

- Enqueue the root node

- While the queue is not empty

- dequeue a node

- do something with the node

- enqueue the left child if it exists

- enqueue the right child if it exists

- This is going to use a queue, just like the BFS you did for your maze solving assignment.

- Code:

void levelOrder(TreeNode *tree) { Queue<TreeNode *>treeQueue; treeQueue.enqueue(tree); while (!treeQueue.isEmpty()) { TreeNode *node = treeQueue.dequeue(); cout << node->value << " "; if (node->left != nullptr) { treeQueue.enqueue(node->left); } if (node->right != nullptr) { treeQueue.enqueue(node->right); } } }