Lecture 11: More Strings

July 8th, 2021

Today: int vs. float, int for indexing, int div, int mod, text files, standard output, print(), file-reading, crazycat example program, debugging with print()

Last Time: brackets(), Try parens()

Did brackets() last time in string3 section. Try the parens() and at_3() problems.

Exercise: parens()

> parens()

'x)x(abc)xxx' -> 'abc'

This is nice, realistic string problem with a little logic in it. Try it on your own later.

s.find() variant with 2 params: s.find(target, start_index) - start search at start_index vs. starting search at index 0. Returns -1 if not found, as usual.

Suppose we have the string '[xyz['. How to find the second '['?

>>> s = '[xyz['

>>> s.find('[') # find first [

0

>>> s.find('[', 1) # start search at 1

4

Thinking about this input: '))(abc)'. Starting hint code, something like this, to find the right paren after the left paren:

left = s.find('(')

...

right = s.find(')', left + 1)

Example: right_left()

'aabb' -> 'bbbbaaaa'

right_left(s): We'll say the midpoint of a string is the len divided by 2, dividing the string into a left half before the midpoint and a right half starting at the midpoint. Given string s, return a new string made of 2 copies of right followed by 2 copies of left. So 'aabb' returns 'bbbbaaaa'.

Where do you cut the string Python?

The back half begins at index 3. The length is 6, so an obvious approach is to divide the length by 2. This actually does not work, and leads to a whole story.

Dividing length by 2 leads to an error...

>>> s = 'Python' >>> mid = len(s) / 3 >>> mid 3.0 >>> s[mid:] TypeError: slice indices must be integers or None or have an __index__ method >>>

Recall: int vs. float

There are two number systems in the computer int for whole-number integers, and float for floating point numbers. The math operators + - * / ** work for both number types, so for many day-to-day computations the int/float distinction hardly matters and is not something you need to think about all the time.

int vs. float - Decimal Point

Floating point numbers have the decimal point when entered or printed and int do not. Operators work with both types the same way. Any float value in an expression promotes the whole result to be float.

>>> 1 + 2 # int addition 3 >>> 1.0 + 2.0 # float addition 3.0 >>> 1.0 + 2 + 3 # any float -> float result 6.0

float - Not For Indexing

One case that requires int is indexing, identifying the int index of an element inside of a collection, as we see here with string, and as we saw before with get_pixel(x, y). Accessing an element at 3.0 does not work.

>>> s = 'Python' >>> mid = len(s) / 2 >>> mid 3.0 >>> s[mid] TypeError: string indices must be integers >>> s[3.0] TypeError: string indices must be integers >>> s[3] 'h' >>>

Division / Produces Floats

The operators + - * **, when given in inputs, produce an int output. But division / is an exception. It always produces a float. Even if the result comes out even, the result is float.

>>> 7 / 2 # float result 3.5 >>> 8 / 2 # even if divides evenly 4.0 >>> 6 / 2 3.0

This is a reasonable rule - very often the result of division cannot be expressed as a whole number. We need a separate operator if we want it to produce the whole-number, int result of division.

So this is the problem with right_left() - using / division to compute the midpoint produces a float index which does not work. We want a "rounds down" int division operator.

Int Division // Produces int

Python has a separate "int division" operator. It does division and discards any remainder, rounding the result down to the next integer.

>>> 7 // 2 3 >>> 6 // 2 3 >>> 9 // 2 4 >>> 8 // 2 4 >> 94 // 10 9 >>> 102 // 4 25

Solve right_left()

'aabb' -> 'bbbbaaaa'

Now solve right_left(). Use // to compute int "mid", rounding down in the case of a string of odd width. Our solution uses decomp-by-var to store name parts of the solution which reads nicely.

Solution Code

def right_left(s):

mid = len(s) // 2

left = s[:mid]

right = s[mid:]

return right + right + left + left

Notice the decomp-by-var strategy: solve a sub-part of the problem, storing the partial result in a variable with a reasonable name. Use the var on later lines. This is decomposition at a small scale - breaking a long line into pieces. Also the variable names make it nicely readable.

right_left() Without Decomp By Var - Yikes!

Here is the solution without the variables - yikes!

return s[len(s) // 2:] + s[len(s) // 2:] + s[:len(s) // 2] + s[:len(s) // 2]

The solution is just one line long, but decomp-var version is more readable. Readability is not to help some other person, it's to help yourself. Bugs are when the code does something unexpected, and readability is at the core of that.

Modulo, Mod % Operator

The "mod" operator % is essentially the remainder after int division. So for example (23 % 10) yields 3 — divide 23 by 10 and 3 is the leftover remainder. The formal word for this us "modulo", but the word is often shortened to just "mod". The mod operator makes the most sense with positive numbers, so avoid negative numbers in modulo arithmetic.

>>> 23 % 10 3 >>> 36 % 10 6 >>> 43 % 10 3 >>> 15 % 0 ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero >>> >>> 40 % 10 # mod result 0 means it divides evenly 0 >>> 17 % 5 2 >>> 15 % 5 0

Mod - Even vs. Odd

A simple use of mod is checking if a number is even or odd - n % 2 is 0 if even, 1 if odd.

>>> 8 % 2 0 >>> 9 % 2 1 >>> 10 % 2 0 >>> 11 % 2 1

crazy_str()

crazy_str(s): Given a string s, return a crazy looking version where the first char is lowercase, the second is uppercase, the third is lowercase, and so on. So 'Hello' returns 'hElLo'. Use the mod % operator to detect even/odd index numbers.

int str Types and Conversion

Q: What is the difference between 123 and '123'? How do they work with the + operator?

>>> 123 + 5 128 >>> >>> 'hi' + 'there' 'hithere' >>> >>> # e.g. line is out of a file - a string >>> # convert str form to int >>> line = '123\n' >>> int(line) 123 >>> >>> # works the other way too >>> str(123) '123'

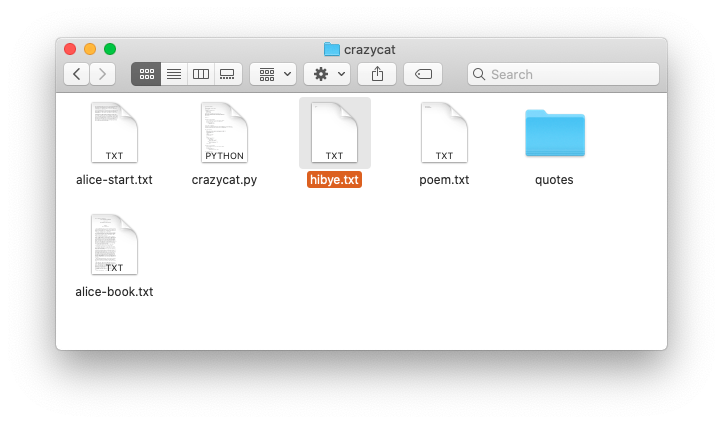

File Processing - crazycat example

We'll use the crazycat example to demonstrate files, file-processing, printing, standard output, and functions.

What is a Text File?

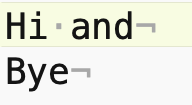

hibye.txt Text File Example

The file named "hibye.txt" is in the crazycat folder. What is a file? A file on the computer has a name and stores a series of bytes. The file data does not depend on the computer being switched on. The file is said to be "non-volatile". More details later.

bibye.txt Contents

Text file: series of lines, each line a series of chars, each line marked by '\n' at end

The hibye.txt file has 2 lines, each line has a '\n' at the end.

The first line has a space, aka ' ', between the two words. Here is the complete contents:

Hi and bye

Here is what that file looks like in an editor that shows little

gray marks for the space and \n:

In Fact the contents of that file can be expressed as a Python string:

'Hi and\nbye\n'

How many chars? How many bytes?

How many chars are in that file (each \n is one char)?

There are 11 chars. The latin alphabet A-Z chars like this take up 1 byte per char. Characters in other languages take 2 or 4 bytes per char. Use your operating system to get the information about the hibye.txt file. What size in bytes does your operating system report for this file?

So when you send a 50 char text message .. that's about 50 bytes sent on the network + some overhead. Text data like this uses very few bytes compared to sound or images or video.

Backslash Chars in a String

Use backslash \ to include special chars within a string literal. Note: different from the regular slash / on the same key as ?.

s = 'isn\'t' # or use double quotes # s = "isn't" \n newline char \\ backlash char \' single quote \" double quote

Aside: Detail About Line Endings

In the old days, there were two chars to end a line. The \r "carriage return", would move the typing head back to the left edge. The \n "new line" would advance to the next line. So in old systems, e.g. DOS, the end of a line is marked by two chars next to each other \r\n. On Windows, you will see text files with this convention to this this day. Python code largely insulates your code from this detail - the for line in f form shown below will go through the lines, regardless of what line-ending they are encoded with.

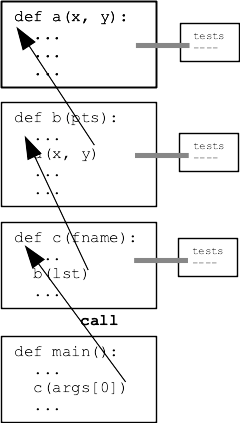

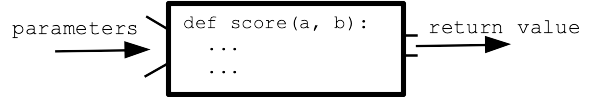

Recall: Program Made of Functions

Q: How does data flow between the functions in your program?

A: Parameters and Return value

Parameters carry data from the caller code into a function when it is called. The return value of a function carries data back to the caller.

This is the key data flow in your program. It is 100% the basis of the Doctests. It is also the basis of the old black-box picture of a function

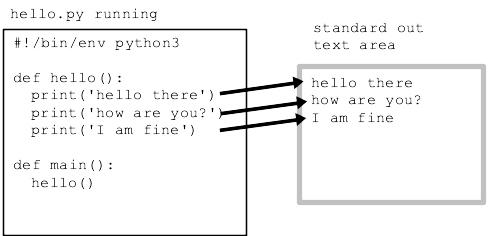

"Standard Output" Text Area

BUT .. there is an additional, parallel output area for a program, shared by all its functions.

There is a Standard Output area associated with every run of a program. It is by default a text area made of lines of text. A function can append a line of text to standard out, and conveniently that text will appear in the terminal window hosting that run of python code. Standard out is associated with the print() function below.

print() function

See guide: print()

>>> print('hello', 'there', '!')

hello there !

>>> print('hello', 123, '!')

hello 123 !

>>> print(1, 2, 3)

1 2 3

print() sep= end= Options

>>> print('hello', 123, '!', sep=':') # sep= between items

hello:123:!

>>> print(1, 2, 3, end='xxx\n') # end= what goes at end

1 2 3xxx

>>> print(1, 2, 3, end='') # suppress the \n

1 2 3>>>

Data out of function: return vs. print

Return and print() are both ways to get data out of a function, so they can be confused with each other. We will be careful when specifying a function to say that it should "return" a value (very common), or it should "print" something to standard output (rare). Return is the most common way to communicate data out of a function, but below are some print examples.

Crazycat Program example

This example program is complete, showing some functions, Doctests, and file-reading.

1. Try "ls" and "cat" in terminal

See guide: command line

Open a terminal in the crazycat directory (see the Command Line guide for more information running in the terminal). Terminal commands - work in both Mac and Windows. When you type command in the terminal, you are typing command directly to the operating system that runs your computer - Mac OS, or Windows, or Linux.

pwd - print out what directory we are in

ls - see list of filenames ("dir" on older Windows)

cat filename - see file contents ("type" on older Windows)

$ ls alice-book.txt crazycat.py poem.txt alice-start.txt hibye.txt quotes $ cat poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme $

2. Run crazycat.py with filename

$ python3 crazycat.py poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme $ python3 crazycat.py hibye.txt Hi and bye $

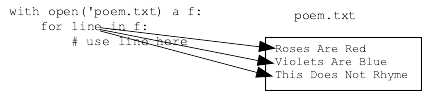

3. Canonical File-Read Code

Here is the canonical file-reading code:

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

# use line in here

Visualization of how the variable "line" behaves for each iteration of the loop:

print_file_plain()

Here is the complete code for the "cat" feature - printing out the contents of a file. Why do we need end='' here? The line already has \n at its end, so we get double spacing if print() adds its standard \n. Run the program with end='' removed and see what it does.

def print_file_plain(filename):

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

# use line in here

print(line, end='')

Run With -crazy Command Line Option

The main() function looks for '-crazy' option on the command line. We'll learn how to code that up soon. For now, just know that main() calls the print_file_crazy() function which calls the crazy_line() helper.

Here is command line to run with -crazy option

$ python3 crazycat.py -crazy poem.txt rOsEs aRe rEd vIoLeTs aRe bLuE tHiS DoEs nOt rHyMe

crazy_str(s) Helper

def crazy_str(s):

"""

Given a string s, return a crazy looking version where the first

char is lowercase, the second is uppercase, the third is lowercase,

and so on. So 'Hello' returns 'hElLo'.

>>> crazy_str('Hello')

'hElLo'

>>> crazy_str('@xYz!')

'@XyZ!'

>>> crazy_str('')

''

"""

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if i % 2 == 0:

result += s[i].lower()

else:

result += s[i].upper()

return result

print_file_crazy()

Important technique: see how how the line string is passed into the crazy_str() helper. The result of the helper is sent to print(). Very compact using parameter/result data flow here.

Key Line: print(crazy_str(line), end='')

The code is similar to print_file_plain() but passes each line through the crazy_str() function before printing. Think about the flow of data in the code below.

def print_file_crazy(filename):

"""

Given a filename, read all its lines and print them out

in crazy form.

"""

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

print(crazy_str(line), end='')

Optional alice-start.txt alice-book.txt

Try running the code with alice-start.txt is the first few paragraphs of Alice in Wonderland, and alice-book is the entire text of the book. Try the entire text.

1. Note how fast it is. Your computer is operating at, say, 2Ghz, 2 billion operations per second. Even if each Python line of code takes, say, 10 operations, that's still a speed that is hard for the mind to grasp.

2. Try running this way, works on all operating systems:

$ python3 crazycat.py -crazy alice-start.txt > capture.txt

What does this do? Instead of printing to the terminal, it captures standard output to a file "capture.txt". Use "ls" and "cat" to look at the new file. This is a super handy way to use your programs. You run the program, experimenting and seeing the output directly. When you have a form you like, use > once to capture the output. Like the pros do it!

Debugging 1-2-3

To write code is to see a lot of bugs. Three ways to debug we've mentioned the first two, but today the third.

1. Look at the exception

Read the exception message and line number. Go look at that line. Many bugs can be fixed right there.

2. Look at the "got" + your code

Don't ask "why is this not working?". Ask "why is the code producing this?". Look at the code, trace through it with your mind. Sometimes "trace through it with your mind" is too hard! In that case try print() below.

3a. Add some print() in the code - server

Instead of tracking the code in your head, add print() to see the state of the variables. This works on the experimental server. Try adding print code in crazy_str() on the server:

def crazy_str(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if i % 2 == 0:

result += s[i].lower()

else:

result += s[i].upper()

print('i:', i, 'result:', result)

return result

Output with print() for the case 'Python'

'pYtHoN' i: 0 result: p i: 1 result: pY i: 2 result: pYt i: 3 result: pYtH i: 4 result: pYtHo i: 5 result: pYtHoN

The experimental server shows the function result first, then the printout below. This can also work in a Doctest. Be sure to remove the print() lines when done - they are temporary scaffolding while building.

3b. Try adding print() to crazy_str() Doctest

In the crazycat.py file. Run the Doctest. Remove the print() when done - it's temporary.