The HyChem approach expresses the fuel pyrolysis and pyrolysis products oxidation in two submodels. Fig. 1 shows the HyChem model structure. The fuel pyrolysis/oxidative pyrolysis is modeled by several experimentally-constrained, lumped reaction steps. The oxidation of the pyrolysis products is modeled by a detailed foundational chemistry model. The two submodels are interconnected. The pyrolysis process provides "reactants" for the oxidation process; the oxidation provides heat and radicals to facilitate the endothermic pyrolysis of the fuel.

Fig. 1. Scematic of the HyChem approach.

Key observations and assumptions [1, 2]

1. In high temperature combustion, large hydrocarbon fuels undergo pyrolysis first, followed by the oxidation of pyrolysis products. These two processes are decoupled in both time and space.

2. The second step, i.e., the oxidation of the pyrolysis products, is rate limiting. Therefore, the composition of the pyrolysis products determines the overall oxidation rate of the fuel and hence, many of the global oxidation properties (ignition delay time, laminar flame speed and extinction).

3. For petroleum-derived fuels, the number of significant pyrolysis products is six to ten in all. Key species may include ethylene (C2H4), hydrogen (H2), methane (CH4), propene (C3H6), 1-butene (1-C4H8), iso-butene (i-C4H8), benzene (C6H6), and tuluene (C7H8), where CH4 and H2 come from the H abstraction of the fuel molecules by CH3 and H radicals, respectively.

4. Most or all of the above species can be measured in a shock tube or flow reactor.

5. The overal combustion chemistry may be modeled by combining experimentally constrained, lumped reaction steps for fuel (oxidative) pyrolysis with a detailed foundational fuel chemistry model to describe the oxidation of the fuel pyrolysis products.

6. In the lumped reaction steps, the stoichiometric coefficients are not a function of pressure, temperature or mixture stoichiometry in the temperature range of 1000-1450 K.

HyChem model formulation

For a hydrocarbon fuel with an average formula of CmHn, the pyrolysis and oxidative pyrolysis of the fuel is formulated as follows:

|

(R1) |

|

(R2) |

where R = H, CH3, O, OH, O2, and HO2. Reaction (R1) represents the C-C fission of the fuel "molecule", and Reaction (R2) describes the H-abstraction reactions followed by β-scission. In such a way, the thermal decomposition of the fuel is described by one C-C fission and six H-abstraction reactions. In the reaction expressions, C4H8 is a mixture of two butene isomers (1-C4H8 and i-C4H8). The species concsidered work for nearly all fuels tested thus far, except for JP-10 for which cyclopentadiene (C5H6) must be considered [3]

The seven lumped reactions discussed above are merged with a detailed foundation chemistry model (USC Mech II [4]). The HyChem model parameters (stoichiometric coefficients and rate coefficients) are derived from suitable shock-tube and flow-reactor experiments. For example, the parameter λ3 can be estimated by the ratio of C3H6 yield to C2H4 yield in legacy experiments (e.g. shock tube and flow reactor). Details can be found in [1] and [2].

Thermochemical data

Thermochemical properties of all the liquid, multicomponent fuels studied are estimated by using a fuel surrogate mixture that closely matches the H/C ratio, average molecular weight, and class composition of a given fuel. For the thermochemical properties of multicomponent liquid fuels, click the following reports for details:

Jet fuels (A1, A2, A3, C1, and C5) [5], the report is part of the Supplementary Material of Ref. [2].

Rocket fuels (RP2-1 and RP2-2) [6], the report is part of the Supplementary Material of Ref. [2].

Gasoline fuels (Shell A and Shell D), the report is part of the Supplementary Material of Ref. [7].

The thermochemical properties of JP-10 are taken from the Third Millennium Ideal Gas and Condensed Phase Thermochemical Database [8].

The transport properties of a multicomponent fuel with an average formula of CmHn is modeled by those of CmH2m+2 n-alkane. The latter are taken from results in a series of recent work on the diffusion coefficients of long-chain molecules and dependence of the counter-flow flame extinction on the molecular diffusivity of large fuels [9-11]. The transport properties of the JP-10 fuel are estimated using the method of corresponding states [12].

Values of the model parameters (stoichiometric and reaction rate coefficients) are derived through a joint fit to the key species time history data from

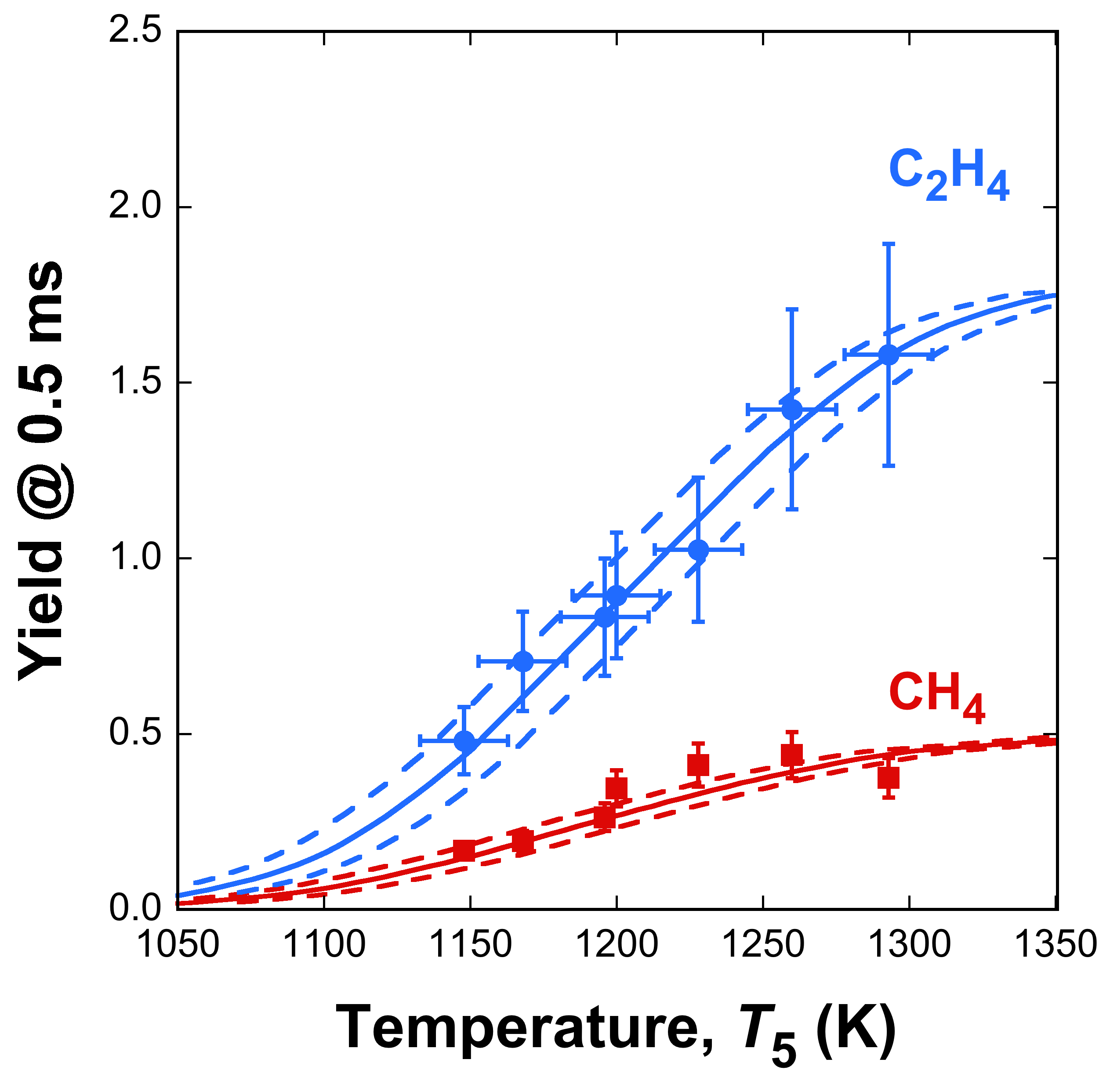

shock tube pyrolysis and oxidative pyrolysis, and flow reactor oxidative pyrolysis experiments. Fig. 2 shows an example of the experimental data and the model fits

of C2H4 and CH4 from Jet A (A2) pyrolysis. Summary comparisons of C2H4 and CH4 yields are shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 4 shows results for the flow reactor experiment, also for the A2 fuel. See the Performance page for additional tests.

Fig. 2. Time histories of C2H4 and CH4 measured (symbols) and simulated (lines) from thermal decomposition of Jet A (A2) fuel in argon in the Stanford shock tube.

The dotted lines are simulations bracketing the ±15 K temperature uncertainty.

Fig. 3. Yields of C2H4 and CH4 measured (symbols) and simulated (lines) from thermal

decomposition of 0.73 % (mol) Jet A (A2) fuel in argon in the Stanford shock tube at a nominal

pressure p5 = 12.4 atm. The dashed lines are simulations bracketing the ±15 K temperature uncertainty.

Error bars represent ±15 K in temperature uncertainty and experimental uncertainties of C2H4 and

CH4 concentrations.

Fig. 4. Time histories of major oxidative pyrolysis species during the early stage of A2 oxidation

(314 ppm A2 in a vitiated oxygen-nitrogen mixture at unity equivalence ratio) in a flow reactor at 1030 K

temperature and 1 atm pressure. Symbols are experimental data; lines are simulations starting at 2.87 ms

using measured species concentration as input of the initial condition. The concentrations of these species,

including those from the vitiated mixture, are given in Table S1 of Ref. [2].

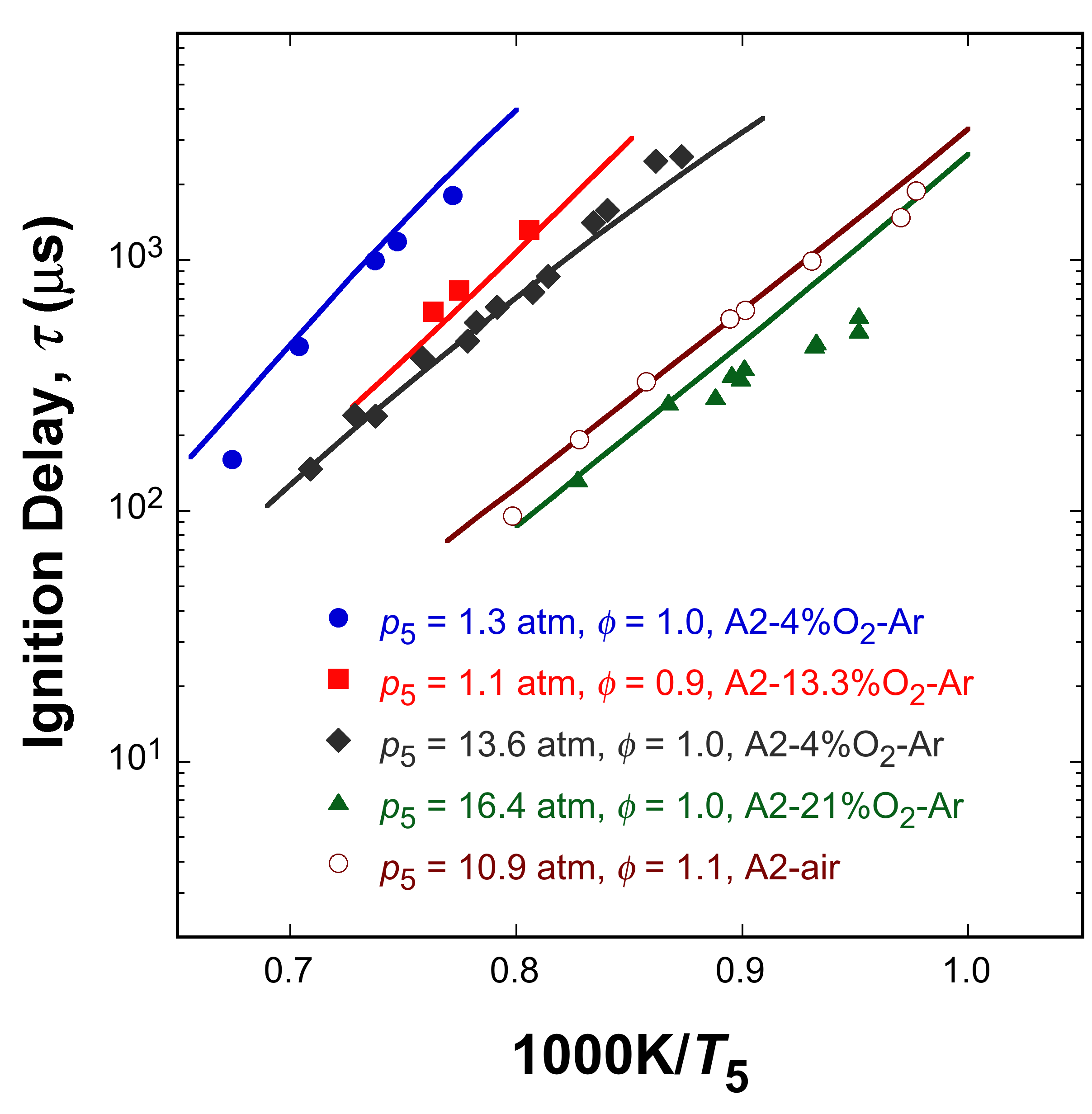

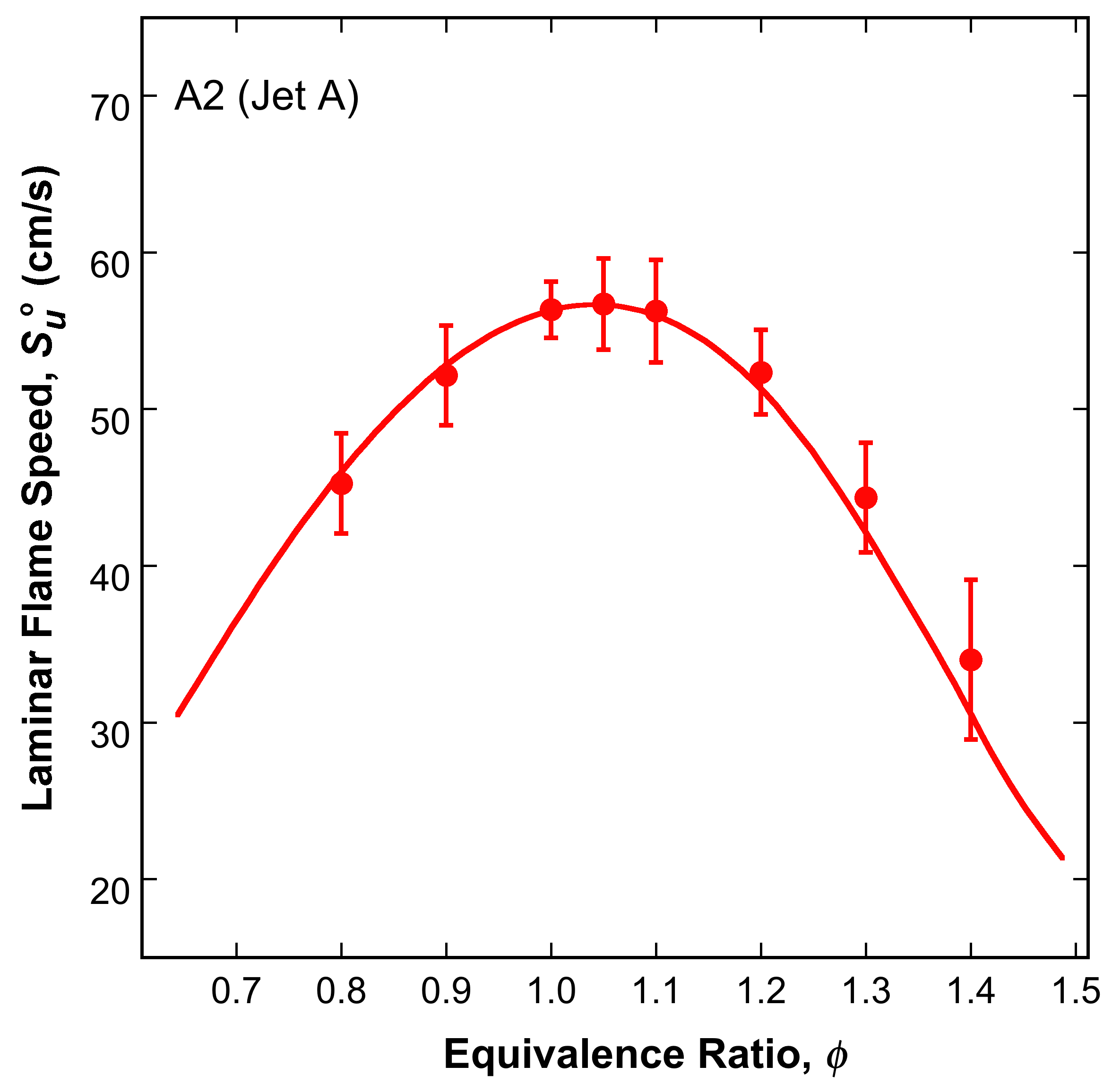

The HyChem model thus derived are tested against global combustion properties. For example, Fig. 5 presents the experimental

and simulated ignition delay times of five Jet A (A2) mixtures over a range of conditions. Fig. 6 shows the comparisons of experimental a

and simulated laminar flame speed and non-premixed flame extinction strain rates of Jet A. For more examples, see the Performance page.

Fig. 5. Measured (symbols) and simulated (solid lines) ignition delay times of

Jet A (A2) under various mixture conditions.

Fig. 6. Experimental (symbols) and simulated (lines) laminar flame speed (left panel) of A2 in air (403 unburned gas temperature)

and extinction strain rate (right panel) of non-premixed A2/N2 against O2 (the A2/N2 jet temperature is 473 K, and

O2 temperature is 300 K), all at 1 atm.

[1] H. Wang, R. Xu, K. Wang, C. T. Bowman,

D. F. Davidson, R. K. Hanson, K. Brezinsky, F. N. Egolfopoulos, A physics-based approach to modeling real-fuel combustion chemistry - I. Evidence from experiments, and thermodynamic, chemical kinetic and statistical considerations, Combustion and Flame 193 (2018) 502-519.

[2] R. Xu, K. Wang, S. Banerjee, J. Shao, T. Parise,

Y. Zhu, S. Wang, A. Movaghar, D.J. Lee, R. Zhao, X. Han, Y. Gao, T. Lu, K. Brezinsky, F.N. Egolfopoulos, D.F. Davidson, R.K. Hanson, C.T. Bowman,

H. Wang, A physics-based approach to modeling real-fuel combustion chemistry - II. Reaction kinetic models of jet and rocket fuels,

Combustion and Flame 193 (2018) 520-537.

[3] Y. Tao, R. Xu, K. Wang, J. Shao, S.E. Johnson, A. Movaghar, X. Han, J. Park, T. Lu, K. Brezinsky, F.N. Egolfopoulos, D.F. Davidson, R.K. Hanson, C.T. Bowman, H. Wang, A physics-based approach to modeling real-fuel combustion chemistry - III. Reaction kinetic model of JP10, Combustion and Flame 198 (2018) pp. 466–476.

[4] H. Wang, X. You, A.V. Joshi,

S.G. Davis, A. Laskin, F. Egolfopoulos, C.K. Law, USC Mech Version II. High-Temperature Combustion Reaction Model of H2/CO/C1-C4 Compounds.

http://ignis.usc.edu/Mechanisms/USC-Mech II/USC_Mech II.htmTransport properties

Model development

Test against combustion data

References

[5] R. Xu, H. Wang, M. Colket, T. Edwards, Thermochemical properties of jet fuels, Interm Report (2015).

[6] R. Xu, H. Wang, M. Billingsley, Thermochemical properties of rocket fuels, Interm Report (2015).

[7] R. Xu, C. Saggese, R. Lawson, A. Movaghar, T. Parise, J.Shao, R. Choudhary, J. Park, T. Lu, R.K. Hanson, D.F. Davidson, F.N. Egolfopoulos, A. Aradi, A. Prakash, V.R.R. Mohan, R. Cracknell, H. Wang, A physics-based approach to modeling real-fuel combustion chemistry - VI. Predictive kinetic models of gasoline fuels, Combustion and Flame 220 (2020) 475-487.

[8] E. Goos, A. Burcat, B. Ruscic, Extended third millennium ideal gas and condensed phase thermochemical database for combustion with updates from active thermochemical tables. http://garfield.chem.elte.hu/Burcat/THERM.DAT.

[9] C. Liu, Z. Li, H. Wang, Drag force and transport property of a small cylinder in free molecule flow: A gas-kinetic theory analysis, Physics Review E 94 (2016) 023102.

[10] C. Liu, W.S. McGivern, J.A. Manion, H. Wang, Theory and experiment of binary diffusion coefficient of n-alkanes in dilute gases, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 120 (2016) 8065-8074.

[11] C. Liu, R. Zhao, R. Xu, F.N. Egolfopoulos, H. Wang, Binary diffusion coefficients and non-premixed flames extinction of long-chain alkanes, Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 36 (2017) 1523-1530.

[12] H. Wang, M. Frenklach, Transport properties of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons for flame modeling, Combustion and Flame 96 (1994) 163-170.