Table of Contents — Stories on this Page

2017

- December 7, 2017 — Software in development at Stanford advances the modeling of astronomical observations

- October 16, 2017 — Stanford experts weigh in on LIGO’s kilanova binary neutron star milestone

- October 2017— Stanford’s Student Space Initiative Group (SSI) Sets Up Shop in HEPL South / End Station III

- January 30, 2017 — NASA's Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope has detected gamma rays eminating from flares on the back side of our sun

2016

- September 15, 2016 — AIAA Honors the Stanford/NASA/Lockheed Martin Gravity Probe B Team with 2016 Space Science Award

- September 1, 2016 — Professor Daniel Palanker becomes Interim Director of HEPL

- August 2, 2016 — Physics Professor Sarah Church relinquishes post as HEPL Director to become senior associate vice provost for undergraduate education

- May 16, 2016 — Stanford engineer Bradford Parkinson, the ‘Father of GPS,’ wins prestigious Marconi Prize

- February 11, 2016 — Stanford Researchers Celebrate Their Collaboration in the Technological Advances Enabling the Long-Sought Detection of Gravitational Waves by the LIGO Observatories

2015

- November 19, 2015 — Volume 32, Issue #22 of the Journal, Classical and Quantum Gravity, Devoted Entirely to the Landmark, 48-Year Stanford/HEPL Gravity Probe B Experiment

- April 27, 2015 — Photovoltaic retinal implant developed by HEPL's Palanker Group, could restore functional sight

- April 27, 2015 — Stanford and UC Berkeley partner on NASA's new effort to detect life on other planets

- January l4, 2015 — Artificial intelligence Helps StanfordPhysicistsPpredict DangerousSolarFlares

2014

- June 19, 2014 — HEPL PhD Candidate’s Charge-Control Experiment is Flight Certified at NASA Ames, Integrated into a Saudi Arabian Satellite and Launched into Orbit Aboard a Russian-Ukrainian Rocket

- March 17, 2014 — New Evidence from Space Supports Stanford Physicist's Theory of How the Universe Began

- February 10, 2014 — HEPL Physicist, Leo Hollberg, and Two Former NIST Colleagues Share 2014 Rank Optoelectronics Prize for Their Development of Chip-Scale Atomic Clock

2013

- November 21, 2013 — Stanford's Fermi Gamma-ray Large Area Space Telescope Detects Most Energetic Gamma-ray Burst On Record

- November 6, 2013 — A Particle Accelerator on a Silicon Chip

- September 1, 2013 — Sarah Church succeeds Peter Michelson as HEPL Director

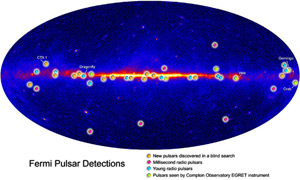

- January 29, 2013 —Fermi-LAT Physicist, Roger Romani, wins 2013 Bruno Rossi Prize

- January 14, 2013 — Roger Blandford Receives Royal Astronomical Society's Top Honor

2012

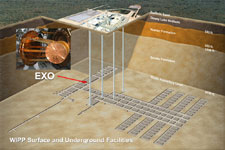

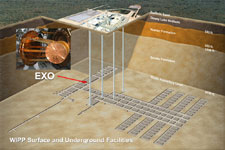

- June 4, 2012 —Underground search for neutrino properties unveils first results

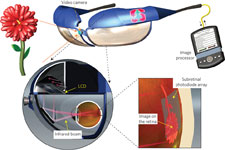

- May 13, 2012 — Restoring sight to the blind with a photovoltaic retinal prosthesis

2011

- August 19, 2011 — New method developed by HEPL's Solar Research Group detects emerging sunspots deep inside the sun

- May 4, 2011 — Gravity Probe B Announces Final Experimental Results in Press and Media Event at NASA Headquarters

- February, 2011 — HEPL's Igor Moskalenko and Stanford Professors Mark Brongersma and Juan Santiago Selected as 2010 APS Fellows

- January 12, 2011 — Fermi Large Area Telescope Team Awarded Rossi Prize

2010

- November 17, 2010 — Palanker Group's Laser Cataract Surgery Technique is Cover Story in November 17th Issue of Science Translational Medicine

- March 11, 2010 — Francis Everitt and Sir Roger Penrose awarded 2010 Trotter Prize and Delivered Trotter Lectures at Texas A&M University

- Winter, 2010 — EXO Takes Clean to an Extreme

- February 11, 2010 — Stanford Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) Launches on NASA SDO Satellite

2009

- December 17, 2009 — Dark Matter Search: Latest CDMS-II Results

- November 2, 2009 — Fermi Telescope Celebrates First Year's Results with Cosmic Reflection Concert

- September, 2009 — Peter Michelson succeeds Blas Cabrera as HEPL Director

- August 2009 —Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope results prominently featured in 8/14 issue of AAAS Science

- June/July, 2009 — Gravity Probe B Data Analysis Update

- May 2009 — NASA's Fermi Telescope Measures Spectrum of Electrons and Positrons; Celebratory 'Cosmic Reflection' Concert

- April 28, 2009 — Bob Byer Awarded the Frederic Ives Medal/Jarus W. Quinn Endowment by the OSA

- February 19, 2009 - NASA's Fermi Telescope

Sees Most Extreme Gamma-ray Blast Yet

- January 5, 2009 - CDMS Leading the Search for Dark Matter in the Form of WIMPs

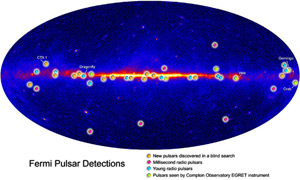

- January 7, 2009 - Fermi Gamma Ray Space Telescope Discovers Slew of New Pulsars

2008

- August 26, 2008 - GLAST Observatory Renamed for Fermi, Reveals Entire Gamma-Ray Sky

- August 2008 - Palanker Research Group Develops Pulsed Electron Avalanche Knife (PEAK)

- August 2008 —Professor Robert Byer Wins 2009 IEEE Photonics Award

- June 11, 2008 — NASA's GLAST Launch Successful

- March 2008 — Crystal bells stay silent as physicists look for dark matter

- January 30, 2008 — On the frontiers of science for decades, a storied building is soon to be razed

2007

- October 31, 2007 — Physicists chase Einstein’s equivalence principle down a hole

Observations of the Geminga pulsar,

shown in this illustration, made by the

High-Altitude Water Cherenkov

Observatory in Mexico indicate that it

and another nearby pulsar are unlikely

to be the origin of excess antimatter

near Earth.

(Image credit: Nahks TrEhnl)

December 7, 2017 — Software in development at Stanford advances the modeling of astronomical observations

Software developed by Stanford astrophysicist Giacomo Vianello models and combines otherwise incompatible astronomical observations. It contributed to recent research into the origin of antimatter near Earth.

Reprint of a news story by Taylor Kabota in the Stanford Report, December 7, 2017

A recent study in Science cast doubt on one formerly favored explanation for why an abundance of positrons – the antimatter counterparts of electrons – has been found near Earth. Two nearby collapsed stars, it turns out, aren’t likely to blame because their positrons couldn’t have traveled as far as the Earth.

This finding, which reopens a debate about a possible role for dark matter in creating those anomalous positrons, required piecing together complex data from the High Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory (HAWC) in Mexico. HAWC, which looks like an array of giant, corrugated steel water tanks, can precisely reconstruct the direction and energy of incoming light – in the form of high-energy gamma-rays – by recording the particle shower that the gamma-ray photons generate when they enter the atmosphere above the detector.

In order to analyze that complex dataset, the HAWC collaboration turned to a software designed by Giacomo Vianello, a research scientist in the lab of Peter Michelson at Stanford University and a co-author of the study. The software, called the Multi-Mission Maximum Likelihood (3ML) framework, was originally designed to combine the data of the Fermi gamma-ray space telescope with the data from other instruments. Its ability to handle data in multiple formats and the unprecedented flexibility of its modeling tools allowed the HAWC team to question the pulsars’ role in generating the unexpected positrons.

“My collaborators and I spent many hours designing and developing 3ML for our research but also for other people to use,” Vianello said. “It is very exciting to see that some researchers find it so useful that they decide to use it for high-impact science like what HAWC published.”

Vianello and the rest of the 3ML team plan to continue improving the software. In addition to working across wavelengths and instruments, they hope it can be used with messengers other than light, such as polarization of electromagnetic radiation, cosmic rays and neutrinos.

The inspiration to create 3ML came from Vianello’s own work with the Fermi gamma-ray space telescope. Fermi has two main instruments, the Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor and the Large Area Telescope (LAT), which is led by Michelson, professor and chair of physics at Stanford. Even though these instruments exist on the same telescope, bringing their data together meant lengthy and cumbersome operations that often sacrificed some of the sensitivity of the LAT.

The situation worsens when the data come from completely different experiments and collaborations.

“It’s like completing a puzzle, where each instrument contributes a piece,” Michelson said. “However, the different pieces of the puzzle are very difficult and sometimes impossible to put together because they have different formats and require very different analysis methods and software.”

Scientists at Fermi have used 3ML for studying gamma-ray bursts. The project has also grown, now including 15 collaborators from the United States and Europe.

“Other missions and instruments have expressed the desire to join the effort and develop plug-ins for their data, so we’ve started working with them toward that,” Vianello said. “Some of them are even joining the development team, which is a very good thing because there is still a lot that can be done to improve 3ML.”

Michelson said he believes that, as it continues to improve, the software could be particularly useful for studying faint sources across multiple wavelengths. It could even play a vital role in solving the mystery of the excess antimatter.

“When completed, 3ML will, for the first time, allow for a powerful combination of Fermi, HAWC and other instruments for detailed analysis of extended sources, such as the one analyzed in the Science paper,” Michelson said.

For More Information:

Research Paper: The Multi-Mission Maximum Likelihood framework (3ML). Authors: Giacomo Vianello, Robert J. Lauer, Patrick Younk, Luigi Tibaldo, James M. Burgess, Hugo Ayala, Patrick Harding, Michelle Hui, Nicola Omodei, Hao Zhou.

arXiv:1507.08343. Submitted 29 Jul 2015

Fermi Gamma-Ray GLAST-StanfordSpace Telescope: Stanford Website

Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope: NASA Website

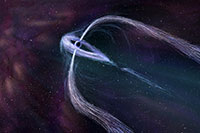

Artist’s rendering of two merging

neutron stars. (Image credit:

NSF/LIGO/Sonoma State

University--A. Simonnet)

October 16, 2017 — Stanford experts weigh in on LIGO’s kilanova binary neutron star milestone

The Advanced LIGO gravitational wave detectors have announced their first observation of a binary neutron star coalescence.

Reprint of a news story by Taylor Kabota in the Stanford Report, October 16, 2017

On August 17, 2017, the two detectors of Advanced LIGO, along with VIRGO, zeroed in on what appeared to be gravitational waves emanating from a pair of neutron stars spinning together – a long-held goal for the LIGO team. An alert went out to collaborators worldwide and within hours some 70 instruments turned their sights on the location a mere 130 million light-years away.

Their combined observations, spanning the electromagnetic spectrum, confirm some of what physicists had theorized about this type of event and also open up new areas of research. Thousands of scientists contributed to this accomplishment, including many at Stanford University, and published the initial findings Oct. 16 in Physical Review Letters and The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“It’s a frighteningly disordered, energetic place out there in the universe and gravitational waves added a new dimension to looking at it,” said Robert Byer, professor of applied physics at Stanford and member of LIGO who provided the laser for the initial detector. “For this event, that new dimension was complemented by the signals from the other electromagnetic wavelengths and all those together gave us a completely different view of what’s going on inside the neutron stars as they merged.”

This observation and the others that are likely to follow could help further the understanding of General Relativity, the origins of elements heavier than iron, the evolution of stars and black holes, relativistic jets that squirt from black holes and neutron stars, and the Hubble constant, which is the cosmological parameter which determines the expansion rate of the universe.

Stanford and LIGO

LIGO is led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology, but Stanford was brought into the collaboration in 1988, largely due to the ultra-clean, stable lasers developed by Byer. The Byer lab developed the chip for the laser in the initial LIGO detector, which they installed in the early 2000s and lasted the lifetime of the initial LIGO project, which concluded in 2010. Lasers for the Advanced LIGO built upon Byer’s earlier work, an effort led by Benno Wilkie of the Albert Einstein Institute Hannover, a former postdoctoral scholar in Stanford’s Ginzton lab.

“We were looking for the problems that LIGO couldn’t actually worry about yet. We wanted to find those and solve them before they became roadblocks,” said Byer. “One thing that allowed Stanford to contribute to LIGO in these extraordinary ways is we have this long tradition of engineering and science working together – and that’s not common. Great credit also goes to our extraordinary graduate students who are the glue that hold it all together.”

Daniel DeBra, professor emeritus of aeronautics and astronautics, designed the original platform for LIGO, a nested system so stable that, in the LIGO detection band, it moves no more than an atom relative to the movement of Earth’s surface. Another crucial element of the vibration isolation system is the silicate bonding technique used to suspend LIGO’s mirrors. As a visiting scholar at Stanford, Sheila Rowan of the University of Glasgow adapted this technique from previous work at Stanford on the Gravity Probe B telescope.

The Dark Energy Camera (DECam), the instrument used by the Dark Energy Survey, was among the first cameras to see in optical light what the LIGO-VIRGO detectors observed in gravitational waves earlier that morning. DECam imaged the entire area within which the object was expected to be and helped confirm that the event was a unique object – and very likely the event LIGO had seen earlier that day.

Many people at Stanford and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory are part of the Dark Energy Survey team. Aaron Roodman, professor and chair of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC, developed, commissioned and continues to optimize the Active Optics System of DECam.

Looking to the future, DeBra and colleagues including Brian Lantz, a senior research scientist who leads the Engineering Test Facility for LIGO at Stanford, are improving signal detection of Advanced LIGO by damping the effects of vibrations on the optics.

Other faculty are improving the sensitivity of the Fermi Large Area Telescope (LAT), a instrument helmed by Peter Michelson, a professor of physics, that can both confirm the existence of a binary neutron star system and rule out other possible sources. Its sister instrument on Fermi, the Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor, detected a gamma ray burst coming from the location given by LIGO and VIRGO 14 seconds after the gravitational wave signal.

LIGO is offline for scheduled upgrades for the next year, but many of the researchers are already working on LIGO Voyager, the third-generation of LIGO, which is anticipated to increase the sensitivity by a factor of 2 and would lead to an estimated 800 percent increase in event rate.

“This is only a beginning. There are many innovations to come and I don’t know where we’re going to be in 10 years, 20 years, 30 years,” said Michelson. “The window is open and there are going to be mind-blowing surprises. That, to me, is the most exciting.”

What’s so special about neutron stars

A neutron star results when the core of a large star collapses and the atoms get crushed. The protons and electrons squeeze together and the remaining star is about 95 percent neutrons. A tablespoon full of neutron stars weighs as much as Mt. Everest.

“Neutron stars have some of the strongest gravity you’ll find – black holes have the strongest – and thus they give us handles on studying strong-field gravity around them to see if it deviates at all from General Relativity,” said Mandeep Gill, the outreach coordinator at KIPAC at SLAC and Stanford, and a member of the Dark Energy Survey collaboration.

Astronomers proposed the existence of neutron stars in 1934. They were first found in 1967, and then in 1975 a radio telescope observed the first instance of a binary neutron star system. From that discovery, Roger Blandford, professor of physics at Stanford, and colleagues confirmed predictions of the General Theory of Relativity.

Blandford said the calculations related to the system Advanced LIGO saw are even more complicated because the stars are much closer together and could only be completed by a computer. This observation continues to support the General Theory of Relativity but Gill is hopeful that additional binary neutron star systems may begin to inform extension to the theory that could reveal how it fits with quantum theory, dark energy and dark matter.

“One of the things I find terribly exciting about these observations is that not only do they confirm aspects of astronomical and relativistic precepts but they actually teach us things about nuclear physics that we don’t properly understand,” said Blandford. “We certainly have many things that we’ve speculated about and thought about – and I have to believe that some of that will be right – but some of it will be much more interesting than what we could anticipate.”

As we observe more of these systems, which scientists anticipate, we may finally understand long-standing mysteries of neutron stars, like whether they have earthquakes on their crust or if, as suspected, they have small mountains that send out their own gravitational wave signal.

“Even though we’ve been doing astronomy since the dawn of civilization, every time we turn on new instruments, we learn new things about what’s going on in the universe,” said Lantz. “If the elements heavier than iron are actually made in events like this, that stuff is here on Earth and it’s likely that was generated by events like this. It gives you sort of a way to reach out and touch the stars.”

Blandford is also KIPAC Division Director in the Particle Physics and Astrophysics Directorate and professor of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC; Byer is also a professor in SLAC’s Photon Science Directorate.

Additional Stanford contributors to the LIGO multi-messenger observation include Edgard Bonilla, Riccardo Bassiri, Elliot Bloom, David Burke, Robert Cameron, James Chiang, Carissa Cirelli, C.E. Cunha, Christopher Davis, Seth Digel, Mattia Di Mauro, Richard Dubois, Martin Fejer, Warren Focke, Thomas Glanzman, Daniel Gruen, Ashot Markosyan, Manuel Meyer, Igor Moskalenko, Nicola Omodei, Elena Orlando, Troy Porter, Anita Reimer, Olaf Reimer, Leon Rochester, Aaron Roodman, Eli Rykoff, Brett Shapiro, Rafe Schindler, Jana B. Thayer, John Gregg Thayer, Giacomo Vianello and Risa Wechsler.

For More Information:

Media Contact for this story: Taylor Kubota, Stanford News Service: (650) 724-7707, Email: tkubota@stanford.edu

Stanford LIGO Group, MIT News Story: LIGO and Virgo make first detection of gravitational waves produced by colliding neutron stars

Stanford LIGO Group, Nobel Prize News Story: Discovery of Gravitational Waves wins 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics

LIGO Scientific Collaboration: News Website

Stanford Student Space Initiative website

October 2017 — Stanford's Student Space Initiative Group (SSI) Sets Up Shop in HEPL South / End Station III

Story by Bob Kahn—HEPL Communications & Webmaster

An energetic group of Stanford undergraduate and graduate students comprising the Stanford Student Space Initiative (SSI) has set up its office/workspace in a warren of rooms on the third floor of HEPL South/End Station III.

Founded in 2013 and now having over 200 members, SSI is a completely student-run organization with the mission of giving future leaders of the space industry the hands-on experience and broader insight they need to realize the next era of space development.

SSI is organized into six teams: High-Altitude Balloons, Rockets, Satellites, Biology, Operations and Policy. Based on their interests and academic specialties, students participate in space-related projects and activities, which range from building and launching high-altitude balloons and rockets to developing a Why Go To Space class in the Stanford Aeronautics and Astronautics Department to inviting speakers from NASA and aerospace companies such as Space X to give presentations. In 2016, a high-altitude balloon launched by the SSI Balloon team from Holister, CA flew for 79 hours, landing in Quebec, Canada—setting a new world record for the longest latex high-altitude balloon flight.

Read full story…

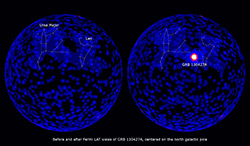

Anmimation showing gamma rays from a

solar flare on the far side of the sun

moving along magnetic field lines to the

front side where they are

detected by the

Fermi Gamma-ray Space Ttelescope.

Animation by NASA GSFC

These solar flares were imaged in

extreme

ultraviolet light by NASA's

STEREO

satellites, which at the time

were viewing

the side of the sun facing

away from Earth.

All three events launched

fast coronal mass

ejections (CMEs).

Scientists think particles accelerated by

the

CMEs rained onto the Earth-facing

side of

the sun and produced the gamma

rays. Click thumbnail above to view

animated images.

Combined images from NASA's Solar

Dynamics Observatory (center) and the

NASA/ESA Solar and Heliospheric

Observatory (red and blue) show an

impressive coronal mass ejection

departing the far side of the sun on

Sept. 1, 2014. This massive cloud raced

away at about 5 million mph and likely

accelerated particles that later produced

gamma rays Fermi detected.

Click t humbnail above to view

animated image.

January 30, 2017 — NASA's Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope has detected gamma rays eminating from flares on the back side of our sun

Reprint of story by Francis Reddy, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

An international science team says NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has observed high-energy light from solar eruptions located on the far side of the sun, which should block direct light from these events. This apparent paradox is providing solar scientists with a unique tool for exploring how charged particles are accelerated to nearly the speed of light and move across the sun during solar flares.

"Fermi is seeing gamma rays from the side of the sun we're facing, but the emission is produced by streams of particles blasted out of solar flares on the far side of the sun," said Nicola Omodei, a member of the Fermi research team at Stanford University's Hansen Experimental Physics Lab in California. "These particles must travel some 300,000 miles within about five minutes of the eruption to produce this light."

Omodei presented the findings on January. 30, 2017 at the American Physical Society meeting in Washington, and a paper entitled Fermi-LAT Observations of High-energy Behind-thd-limb Solar Flares, describing the results were published online in The Astrophysical Journal on Jan. 31.

"Observations by Fermi's LAT continue to have a significant impact on the solar physics community in their own right, but the addition of STEREO observations provides extremely valuable information of how they mesh with the big picture of solar activity," said Melissa Pesce-Rollins, a researcher at the National Institute of Nuclear Physics in Pisa, Italy, and a co-author of the paper.

The hidden flares occurred Oct. 11, 2013, and Jan. 6 and Sept. 1, 2014. All three events were associated with fast coronal mass ejections (CMEs), where billion-ton clouds of solar plasma were launched into space. The CME from the most recent event was moving at nearly 5 million miles an hour as it left the sun. Researchers suspect particles accelerated at the leading edge of the CMEs were responsible for the gamma-ray emission.

Large magnetic field structures can connect the acceleration site with distant part of the solar surface. Because charged particles must remain attached to magnetic field lines, the research team thinks particles accelerated at the CME traveled to the sun's visible side along magnetic field lines connecting both locations. As the particles impacted the surface, they generated gamma-ray emission through a variety of processes. One prominent mechanism is thought to be proton collisions that result in a particle called a pion, which quickly decays into gamma rays.

In its first eight years, Fermi has detected high-energy emission from more than 40 solar flares. More than half of these are ranked as moderate, or M class, events. In 2012, Fermi caught the highest-energy emission ever detected from the sun during a powerful X-class flare, from which the LAT detected highenergy gamma rays for more than 20 record-setting hours.

NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope is an astrophysics and particle physics partnership, developed in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Energy and with important contributions from academic institutions and partners in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Sweden and the United States.

Francis Reddy (Syneren Technologies): Lead Science Writer

Scott Wiessinger (USRA): Lead Producer

Tom Bridgman (GST): Data Visualizer

Scott Wiessinger (USRA): Animator

For More Information:

Original Francis Reddy article on NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Website

NASA Goddard Media Studios: Fermi Sees Gamma Rays from Farside Solar Flares (January 30, 2017)

National Geographic Online Story:

Our Sun Produces Bizarre Radiation Bursts—Now NASA Knows Why (February 14, 2017)

AIAA Space 2016 Program Cover

Clcik to view AIAA Space 2016 web page

and download PDF copy of program

HEPL Emeritus Professor Francis Everitt,

Principal Investigator of Gravity Probe

B,

accpting the 2016 AIAA Space Science

Award

(Image credit: Diane Larson)

AIAA 2016 AIAA Space Science

Award

Image credit: Diane Larson)

2016 AIAA Space Science

Award

Medallion

(Image credit: Diane Larson)

September 15, 2016 — AIAA Honors the Stanford/NASA/Lockheed Martin Gravity Probe B Team with 2016 Space Science Award

Every election year, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) hosts a Space and Astronautics Forum and Exposition. This year’s forum and exhibition was called AIAA Space 2016, and was held at the Long Beach, CA Convention Center from September 13-15.

The theme of Space 2016 was: Open Space: Opportunities for the Global Community.

This year’s forum and exhibition included six main sections:

Plenary Program

The plenary program began with talks by NASA Administrator, Charles Bolden Jr., Winston Beauchamp and Steve Jurveston. Other plenary talks focused on two themes: Technologies for the New LEO Economy and Next Stop: Mars.

Forum 360

The Forum 360 panel discussions built on the themes and discussions of each day’s opening plenary session. Topics included:

- Icy Moons and Ocean Worlds

- Commercial Crew Update

- Thriving Within Complexity

- Limiting or Unlimited: Envisioning a Free Market Space Industry

- Earth Observations: Space & the Paris Agreement

- Launch 2020

- On-Orbit Satellite Servicing

- Space Traffic Management

- Global Perspectives

Technical Program

The technical program contains more than 650 technical papers from about 600 government, academic, and private institutions in 28 countries reporting on the latest in space and astronautics research, and offering scores of opportunities for collaboration and discussion on high-impact topics.

Continuing Education

A number of continuing education courses were offered during the conference.

Recognition

Recognition events included the William H. Pickering Lecture with Juno project manager Nybakken and principal investigator Bolton, Wanda Austin delivering the Yvonne C. Brill Lecture, the von Kármán Lecture and a recognition luncheon to celebrate achievements in space and astronautics.

During the Recognition Luncheon, seven awards were presented, including the Space Science Award given to the Gravity Probe B team “For performing with NASA support two revolutionary new tests of Einstein’s theory of gravity, general relativity, with cryogenic gyroscopes in Earth orbit.” The award was accepted by Stanford Research Professor Emeritus, Francis Everitt, Principal Investigator of the Gravity Probe B mission, which was administered by HEPL for nearly half a century, from first NASA funding in 1963 through the spacecraft launch in April 2004, the final results announcement in 2011 and, most recently, the publication of the November 2015 focus issue of the journal, Classical and Quantum Gravity, containing a preface and 21 scientific and technical papers covering every aspect of this landmark experiment and space mission.

Special Events

During special events, conference participants had opportunities to Meet and hear stories from astronauts; network during receptions, luncheons, and poster sessions; attend book signings, explore the exposition hall, and make a silent auction bid for the benefit of the AIAA Foundation.

Space 2016 included nearly 1,500 participants from 28 countries. More than 650 papers were delivered, covering the latest innovation in astrodynamics, space technology, exploration and operations. The conference also included dedicated events for students and young professionals and an evening of astronaut stories.

For More Information:

AIAA Space 2016 web page

Stanford Gravity Probe B Website

Gravity Probe B History

Special November 19, 2015 issue of Classical and Quantum Gravity

Professor Daniel Palanker

Interim HEPL Director

for 2016-17 Academic Year

September 1, 2016 — Ophthalmology Professor Daniel Palanker accepts position as Interim HEPL Director for the 2016-17 Academic Year

On September 1, 2016, professor Daniel Palanker became the new Director of HEPL. Dr. Palanker is the twelfth person to oversee and direct the lab's activities during its 65-year history, beginning in 1951, when the lab was founded as the Stanford "High Energy Physics Lab" (abbreviated HEPL). In 1990, the lab was renamed the "W.W. Hansen Experimental Physics Lab", honoring pioneering physicist and engineer, William W. Hansen.

The directorship of HEPL is a rotating position among the faculty members whose research programs are administered by HEPL. Having just completed her three-year term as HEPL Director, Professor Sarah Church is becoming a senior associate vice provost for Undergraduate Education.

Professor Palanker is working at the interface of physics and medicine. His group studies interactions of electric field with biological cells and tissues, and develops optical and electronic technologies for diagnostic, therapeutic, surgical and prosthetic applications, primarily in ophthalmology. These studies include laser-tissue interactions with applications to ocular therapy and surgery, as well as interferometric imaging of neural signaling. Dr. Palanker is also developing various electro-neural interfaces, including retinal prosthesis for restoration of sight to the blind, and electronic control of secretory glands and blood vessels.

Several of his developments are in clinical practice world-wide: Pulsed Electron Avalanche Knife (PEAK PlasmaBlade), Patterned Scanning Laser Photocoagulator (PASCAL), and OCT-guided Laser System for Cataract Surgery (Catalys). Several others are in clinical trials: Gene therapy of the retinal pigment epithelium (Ocular BioFactory); Neural stimulation for enhanced tear secretion (TearBud, Allergan Inc.); Smartphone-based ophthalmic diagnostics and monitoring (Paxos, DigiSight Inc.).

Dr. Palanker is going to lead a transition of HEPL into a hub for physics-centered interdisciplinary collaborations at Stanford, representing multi-faceted interfaces of Physics with Engineering, Neuroscience and Medicine.

You can read more about the colorful history of HEPL and its previous directors on the About HEPL page of this web site.

Physics Professor Sarah Church

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

September 1, 2016 — Physics Professor Sarah Church relinquishes post as HEPL Director to become senior associate vice provost for undergraduate education

Church, who will assume her new role Sept. 1, succeeds Stanford biology Professor Elizabeth A. "Liz" Hadley, who will complete her three-year term on Aug. 31.

Excerpted from a news story by Kathleen J. Sullivan in the Stanford Report, August 2, 2016

Stanford physics Professor Sarah Church will become the senior associate vice provost for undergraduate education on Sept. 1. Harry J. Elam Jr., vice provost for undergraduate education, recently announced the appointment.

Elam said Church will assist and advise him on the management of the Office of the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education (VPUE ) and on additional matters related to undergraduate education across campus.

Church chaired the Committee on Undergraduate Standards and Policies from 2013-2016, which in recent years has developed the pilot program for the joint majors program and new policies governing coterminal master’s degrees. She served on the ad hoc committee that designed Stanford’s new course-evaluation form.

Church, who joined Stanford’s faculty in 1999, served as the director of the Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory from 2013-2016 and the deputy director of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology from 2007-2011.

Her research is focused on understanding how galaxies are formed and how they are evolving. As part of this effort, the Church Group is building an experiment to map the large-scale distribution of highly redshifted carbon monoxide.

Church also is leading the Argus experiment, a 16-pixel radio spectrometer at the 100-meter Green Bank Telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia – the world’s largest, fully steerable radio telescope – that will investigate star formations in nearby galaxies and our own.

In 2014, Stanford named Church the Pritzker University Fellow in Undergraduate Education in recognition of her extraordinary contributions to undergraduate education.

Elam said he is very excited that Church is joining VPUE in the fall.

Read Kathleen Sullivan's full story in the Stanford Report, August 2, 2016

Aero/Astro Professor Emeritus Brad

Parkinson at Stanford.

(Image credit: Bradford Parkinson)

Marconi Prize Trophy. To be awarded to

Professoe Emeritus, Bradford Parkinson

in November 2016.

Artist's rendering of a GPS satellite

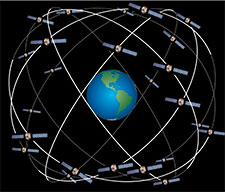

The GPS Satellite Constellation:

24 satellites

in 6 earth-centered orbital

planes with four

operational satellites

and a

spare satellite

slot in each plane.

Stanford engineering graduate students,

standing in

front of a GPS-controlled tractor

Read Story on the GP-B Website

April 2006 — Space Technology Hall

of Fame Award for

development and

commercialization of

GPS precision

guidance technology.

Read Story on GP-B Website

May 20, 2016 — Brad Parkinson

interviewed on NPR Science Friday:

"How

GPS

Found It's Way"

May 16, 2016 — Stanford engineer Bradford Parkinson, the ‘Father of GPS,’ wins prestigious Marconi Prize

The Marconi Prize is awarded each year to recognize major advances in the communications field that benefit humanity.

This year's Marconi award ceremony will occur in Palo Alto, in conjunction with the Stanford Center for Position, Navigation and Time annual symposium in November.

A news story by Bjorn Carey in the Stanford Report, May 16, 2016

It is difficult to imagine that 50 years ago, practically no one wanted to fund the development of a Global Positioning System (GPS). Not only were governments uninterested in funding such a project, they didn’t consider it useful.

Today, Bradford Parkinson, the Edward C. Wells Professor in the School of Engineering, Emeritus, at Stanford, has been awarded the Marconi Prize for his role in guiding the development of GPS from an orphaned project to a technology that is deeply seeded in nearly every aspect of modern life. The $100,000 Marconi Prize, given annually, recognizes major advances in the communications field that benefit humanity.

t all started in late 1972, when Parkinson, then a colonel in the Air Force, was tasked with reviving a foundering USAF program called 621B, which called for creating a global navigation system using satellites. He was initially reluctant to take on the task, given its ugly duckling reputation. Although he soon ran into the same budget issues and infighting within the Department of Defense that had stonewalled his predecessors, Parkinson quickly realized the project’s potential. And he has the pen-and-paper sketches of GPS-guided driving systems to prove it.

“I was certainly a zealot for GPS in any sense of the word,” Parkinson said. “And zealots are not easily discouraged.”

Indeed, he and his team of talented engineers pushed and pushed, drawing up new system plans and making impassioned pitches to military and government officials until finally, in December 1973, they got the green light.

The novel plan called for a network of satellites, each broadcasting the same signal frequency and outfitted with incredibly precise atomic clocks that provide the heartbeat of the system. A receiver on the ground can pick up these signals, the location of the satellite and the exact time that the signal was broadcast – this is where the atomic clocks are essential – to determine its location on Earth with incredible precision.

Funding secured, the first GPS satellite was launched 44 months later – lightning speed in the satellite business. The signal was open to both military and civilian users, a decision Parkinson fought for vigorously, and to which he attributes the current ubiquity of the technology. Today there are 30 Global Positioning satellites robing the planet, providing timing and location data that guides automated agricultural equipment, helps land planes, tracks your running routes and plots the shortest driving route home from work.

After retiring from military service as an Air Force colonel in 1984, Parkinson joined the faculty at Stanford and inspired a new generation of GPS scientists to develop hundreds of system enhancements and applications. While he describes his time here as a student (PhD ’66) as an intellectual delight, coming back as a member of the faculty was “even better.”

“It wasn’t just my colleagues in Aero/Astro who were very skilled, but the young men and women I taught were the absolute cream of the universities of the United States. The best and the brightest,” he said. “I’m still amazed at the things we accomplished. It was just awesome.”

Parkinson and his allied faculty and students developed the concept and first demonstration of the Federal Aviation Administration’s now-operational GPS integrity system, called WAAS, and, with his students, demonstrated the first GPS auto-guided farm tractor, now an $800 million worldwide GPS farming business. In 1992 they demonstrated the first completely blind landing of a commercial airline.

“What was unique back then about Stanford was that department boundaries were really fuzzy. A lot of our work involved professors and students from everywhere around campus,” Parkinson said. “And, frankly, that’s the real world. It was a truly collegial place to be, and I loved every minute.”

Despite those prescient sketches of GPS guidance systems in cars, Parkinson said he is still amazed at all the applications people have developed based on the technology. He does regret, however, that the prevalence of the technology has eroded people’s map-reading skills.

“It grieves me that we’ve lost some of our situational awareness,” he joked, echoing language from his military background. “When I am sailing, I continuously cross-check the GPS. I trust it, but I make sure to verify.”

Parkinson is the latest Stanford-affiliated scientist to win the Marconi Prize, given each year to recognize significant advancements in communication technologies. Past winners with Stanford ties include Martin Hellman, John Cioffi, Arogyaswami Paulraj, Ron Rivest, Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

For More Information

Marconi Society Announcement of Professor Parkinson's Award

Stanford Report News Story by Bjorn Carrey, May 16, 2016

Stanford GPS Lab website

Stanford Center for Position, Navigation and Time website

Stanford Profiles — Professor Bradford Parkinson

Bradford Parkinson's Role in Managing the Stanford/NASA Gravity Probe B Mission

From Einstein to Farming: The Adaptation of GPS Satellite Positioning Technology for Precision Farming (Gravity Probe B Website Story)

The GPS Wiki page

APS Physical Review Letters journal

article documenting the LIGO detection on

14 September 2015

of

gravitational waves

from a binary black

hole merger.

Photo collage from the Stanford LIGO Lab

(Click to view full size.)

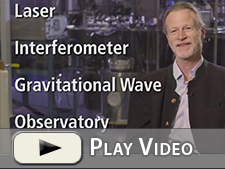

View 2-minute Stanford LIGO Lab video by

Kurt Hickman and Aaron Kehoe

View PHD Comics enlightening and

entertaining

3.5 min YouTube video on

gravitational waves and

their detection

by LIGO.

View 5.5-minute MIT video on LIGO and

its first confirmed detection

of gravitational

waves on

14 September 2015

View 70-minute streaming YouTube video

of the 11 Feb 2016 NSF Press Conference

announcing the first

confirmed LIGO

detection of gravitational

waves on

14 Sep 2015.

February 11, 2016 — Stanford Researchers Celebrate Their Collaboration in the Technological Advances Enabling the Long-Sought Detection of Gravitational Waves by the LIGO Observatories

Excerpted from a news story by Bjorn Carey in the Stanford Report, February 11, 2016

Today an international team of scientists excitedly announced that they had directly observed gravitational waves, often described as ripples in the fabric of spacetime. The discovery of gravitational waves confirms a prediction that Albert Einstein made nearly 100 years ago to shore up his general theory of relativity.

The detection was made by the twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors, an experiment led by researchers at Caltech and MIT that includes more than 1,000 affiliated scientists, including several Stanford physicists and engineers who have played key roles in the program since it was launched. The instrument systems that made the detection possible were built in part on a legacy of interdisciplinary technological advances made by Stanford scientists.

"LIGO is by far the most precise measurement machine that man has ever built," said Robert L. Byer, the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Applied Physics at Stanford, and an original member of the LIGO team. "It's finally sensitive enough to see the bells that are ringing in the universe."

The ringing bell that LIGO heard early in the morning of Sept. 14, 2015, was the result of two massive black holes merging together 1.3 billion light-years away. As the two black holes spiraled around each other, they radiated energy in the form of gravitational waves. While they merged into one even more massive black hole, they released three solar masses of energy.

"This was a huge signal," said Martin Fejer, a professor of applied physics. "It's more energy than our sun will release in its entire lifetime, and it all happened in about a fifth of a second as these two massive black holes coalesced."

Although the peak power output of the event was about 50 times that of the whole visible universe, it required an extremely sensitive device to detect the ensuing gravitational waves. LIGO consists of twin instruments, located 1,865 miles apart in Louisiana and Washington. Each of these instruments involves a single laser, each directed into two 4-kilometer-long arms that run perpendicular to one another.

As a gravitational wave passes through a detector, it distorts spacetime such that one arm lengthens, and the other shortens. By comparing the disturbances at the two detectors, the scientists can confirm the direct detection of a gravitational wave.

"We spend a lot of time making sure that the instruments are very reliable, it doesn't have any funny noise glitches, so you wonder is this a noise glitch or is this a real signal?" said Lantz, who is a senior research scientist in the Gintzon Lab at Stanford. "We [the LIGO team] immediately went through all the things that we know can cause glitches. I started looking around for earthquakes anywhere in the world that might have triggered this, and for funny misbehaviors of our instruments. But we didn't see any."

After carefully considering and eliminating all other possibilities, the LIGO researchers came to the black hole conclusion.

Separating the signal from the noise

Making the detection is incredibly difficult, in part because the amount that a gravitational wave affects the detector arms is incredibly small, only about a thousandth the diameter of an atom's nucleus. To give that some perspective, it's comparable to being able to detect if the distance between the sun and Earth increased by the width of an atom. Eliminating noise from the system has been a central challenge since LIGO's inception, and one in which Stanford research has contributed in several ways.

First, the heart of the instrument, its 1-micron, solid-state laser, was developed through Stanford. Compared to technology being used at that time, these lasers were significantly more reliable but, more important, smaller. By scaling down to a single, monolithic chip, the researchers were able to greatly reduce the instabilities caused by acoustic noise.

Hydraulic and electromagnetic systems developed by Daniel DeBra, the Edward C. Wells Professor of Engineering, Emeritus, moves the mirrors to compensate for the tidal stretching of Earth's crust. Motion of the ground is another major source of noise affecting LIGO. DeBra and Lantz have taken the lead on helping implement measures to prevent these motions from influencing the detectors, reducing vibrational disruptions caused by passing trucks and trains, earthquakes and even the moon.

Another source of noise comes from the mirrors that reflect the lasers in the arms of the detectors. Thermal energy in the mirrors causes the mirror faces to vibrate, which can lead to motions that interfere with the observation of gravitational waves. Modeling these effects and finding materials that minimize these vibrations has been a major focus of Fejer's work, which contributed to the eventual design of the mirrors used in Advanced LIGO. This work continues together with Jonathan Stebbins, a professor of geological sciences, and Riccardo Bassiri, a research associate, who are helping to identify and test high-performance glassy materials to further reduce this noise source in future detectors. Experiments on these materials are being conducted at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, with staff scientist Apurva Mehta. Further reduction in the thermal vibrations was obtained through the design of pure silica wires to suspend the mirrors, developed by physicists Norna Robertson and Sheila Rowan.

"While this is a physics experiment, there were challenges in optics and photonics and precision controls engineering and materials science," Fejer said. "Faculty members from all over campus – Applied Physics, Mechanical Engineering, Aeronautics and Astronautics, SLAC and the School Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences – all participated. The interdisciplinary nature of the faculty at Stanford who enjoy bringing their knowledge and tools to bear on broader problems made Stanford an excellent environment in which to make these contributions to the larger project."

LIGO research is supported by the National Science Foundation and is carried out by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC), a group of more than 1,000 scientists from universities around the United States and in 14 other countries. More than 90 universities and research institutes in the LSC develop detector technology and analyze data, and approximately 250 students are strong contributing members of the international collaboration.

Read Bjorn Carey's full story from Stanford News, February 11, 2016

More Information About LIGO and Gravitational Waves

Caltech LIGO Information and News web page

MIT LIGO Information and News web page

LIGO Information and News web page

National Science Foundation web site

New York Times: Gravitational Waves Detected, Confirming Einstein’s Theory by Dennis Overbye

New York Times: Finding Beauty in the Darkness by Lawrence Krauss

Washington Post: Einstein predicted gravitational waves 100 years ago. Here’s what it took to prove him right. by Sarah Kaplan

New Yorker Magazine: Gravitational Waves Exist: The Inside Story of How Scientists Finally Found Them by Nicola Twilley

CQG 19 Nov 2015

Focus Issue on

Gravity Probe B

GP-B in a Nutshell: A 2-page overview

of the GP-B Experiment (PDF)

GP-B in a Nutshell Video: A 14-minute

YouTube

video

overview of the GP-B

Experiment

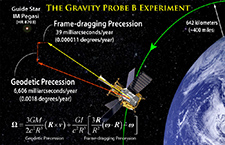

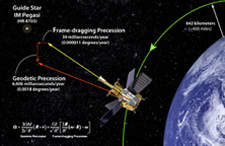

Einstein's predicted geodetic and frame-

dragging effects, with the Schiff

Equation for calculating them.

(Click to enlarge image.)

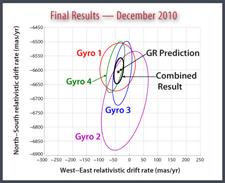

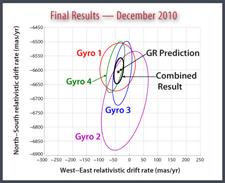

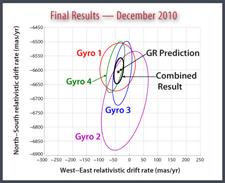

Graph of the results for each gyroscope

individually, and all four gyroscopes

combined.The area inside each colored

ellipse represents a 95% conficence

interval for a gyroscope's measurement

of both the N-S (geodetic) and the W-E

(frame-dragging) effects.

(Click to enlarge image.)

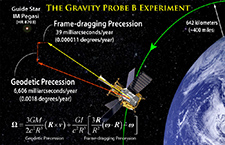

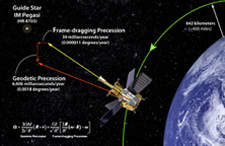

November 19, 2015 — Volume 32 Issue #22 of the Journal, Classical and Quantum Gravity, Devoted Entirely to the Landmark, 50-Year Stanford/HEPL Gravity Probe B Experiment

In November 1915, Albert Einstein presented his field equations—the basis of his general theory of relativity—to the Prussian Academy of Science. Exactly 100 years later, a definative volume detailing the science, technologies and data analysis of the landmark Gravity Probe B experiment was published in a special focus issue of the Institute of Physics Journal, Classical and Quantum Gravity (Volume 32, Number 22, 19 November 2015).

Gravity Probe B (GP-B) was a 48-year HEPL/NASA/Lockheed Martin experimental physics mission that used four ultra-precise, spherical gyroscopes and a telescope, housed in a satellite orbiting 642 km (400 mi) above the Earth, to measure directly, with unprecedented accuracy, two extraordinary effects predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity: 1) the geodetic effect—the amount by which the Earth warps the local spacetime in which it resides and 2) the frame-dragging effect—the amount by which the rotating Earth drags its local spacetime around with it.

First proposed in 1960 by Leonard Schiff, then chairman of the Stanford Physics Department and funded by NASA from 1963-2008, the GP-B spacecraft finally launched on 20 April 2004. Experimental data collection began at the end of August 2004 and lasted for 50 weeks, followed by five weeks of instrument calibration testing. Data analysis commenced in October 2005 and concluded early in 2011. The final results, verifying Einstein's predicted geodetic and frame-dragging measurements, were announced at a press conference at NASA Headquaters on 4 May 2011.

Since that time, members of the GP-B team have been busy documenting all aspects of this landmark experiment in 21 peer-reviewed papers that have now been collectively published in the CQG focus issue, along with a preface by Classical and Quantum Gravity editor, Clifford Will.

Below is the table of contents of the CQG Focus issue on the GP-B experiment, with links to each of the 21 papers in the issue. Note that some of the papers are marked OPEN ACCESS. PDF full-text links to these papers are available free of charge on the respective CQG web pages linked from the table of contents below. For all the other papers, abstracts are available on the respective CQG web pages, with options to purchase the full-text articles for people or institutions that do not have IOP/CQG subscriptions.

Preface

Mission Overview Papers

- 224001 OPEN ACCESS — The Gravity Probe B test of general relativity. C W F Everitt, B Muhlfelder, D B DeBra, B W Parkinson, J P Turneaure, A S Silbergleit, E B Acworth, M Adams, R Adler, W J Bencze, J E Berberian, R J Bernier, K A Bower, R W Brumley, S Buchman, K Burns, B Clarke, J W Conklin, M L Eglington, G Green, G Gutt, D H Gwo, G Hanuschak, X He, M I Heifetz, D N Hipkins, T J Holmes, R A Kahn, G M Keiser, J A Kozaczuk, T Langenstein, J Li, J A Lipa, J M Lockhart, M Luo, I Mandel, F Marcelja, J C Mester, A Ndili, Y Ohshima, J Overduin, M Salomon, D I Santiago, P Shestople, V G Solomonik, K Stahl, M Taber, R A Van Patten, S Wang, J R Wade, P W Worden Jr, N Bartel, L Herman, D E Lebach, M Ratner, R R Ransom, I I Shapiro, H Small, B Stroozas, R Geveden, J H Goebel, J Horack, J Kolodziejczak, A J Lyons, J Olivier, P Peters, M Smith, W Till, L Wooten, W Reeve, M Anderson, N R Bennett, K Burns, H Dougherty, P Dulgov, D Frank, L W Huff, R Katz, J Kirschenbaum, G Mason, D Murray, R Parmley, M I Ratner, G Reynolds, P Rittmuller, P F Schweiger, S Shehata, K Triebes, J VandenBeukel, R Vassar, T Al-Saud, A Al-Jadaan, H Al-Jibreen, M Al-Meshari and B Al-Suwaidan

- 224002 —The three-fold theoretical basis of the Gravity Probe B gyro precession calculation. Ronald J Adler

- 224003 — Spacetime, spin and Gravity Probe B. J M Overduin

Payload Technologies Papers

- 224004 — The Gravity Probe B gyroscope. S Buchman, J A Lipa, G M Keiser, B Muhlfelder and J P Turneaure

- 224005 OPEN ACCESS — The Gravity Probe B electrostatic gyroscope suspension system (GSS).W J Bencze, R W Brumley, M L Eglington, D N Hipkins, T J Holmes, B W Parkinson, Y Ohshima and C W F Everitt

- 224006 — Gravity Probe B gyroscope readout system. B Muhlfelder, J Lockhart, H Aljabreen, B Clarke, G Gutt and M Luo

- 224007 — Precision spheres for the Gravity Probe B experiment. F Marcelja, D B DeBra, G M Keiser and J P Turneaure

- 224008 — The design and performance of the Gravity Probe B telescope. Suwen Wang, J A Lipa, D-H Gwo, K Triebes, J P Turneaure, R P Farley, D Davidson, K A Bower, E B Acworth, R J Bernier, L W Huff, P F Schweiger and J H Goebel

- 224009 OPEN ACCESS — Gravity Probe B cryogenic payload. C W F Everitt, R Parmley, M Taber, W Bencze, K Burns, D Frank, J Kolodziejczak, J Mester, B Muhlfelder, D Murray, G Reynolds, W Till and R Vassar

- 224010 — Porous plug for Gravity Probe B. Suwen Wang, C W Francis Everitt, David J Frank, John A Lipa and Barry F Muhlfelder

- 224011 OPEN ACCESS — Control of fluid mass center in the Gravity Probe B space mission Dewar. D Frank

Spacecraft Technologies Papers

- 224012 — Gravity Probe B spacecraft description. Norman R Bennett, Kevin Burns, Russell Katz, Jon Kirschenbaum, Gary Mason and Shawky Shehata

- 224013 — Gravity Probe B data system description. Norman R Bennett

- 224014 — Timing system design and tests for the Gravity Probe B relativity mission. J Li, G M Keiser, J M Lockhart, Y Ohshima and P Shestople

- 224015 — Precision attitude control of the Gravity Probe B satellite. J W Conklin, M Adams, W J Bencze, D B DeBra, G Green, L Herman, T Holmes, B Muhlfelder, B W Parkinson, A S Silbergleit and J Kirschenbaum

- 224016 — Proportional helium thrusters for Gravity Probe B. D DeBra, W J Bencze, C W F Everitt, J VandenBeukel and J Kirschenbaum

- 224017 — Gravity Probe B orbit determination. P Shestople, A Ndili, G Hanuschak, B W Parkinson and H Small

Data Analysis/Results Papers

- 224018 OPEN ACCESS — Gravity Probe B data analysis: I. Coordinate frames and analysis models. A S Silbergleit, G M Keiser, J P Turneaure, J W Conklin, C W F Everitt, M I Heifetz, T Holmes and P W Worden Jr

- 224019 OPEN ACCESS — Gravity Probe B data analysis: II. Science data and their handling prior to the final analysis. A S Silbergleit, J W Conklin, M I Heifetz, T Holmes, J Li, I Mandel, V G Solomonik, K Stahl, P W Worden Jr, C W F Everitt, M Adams, J E Berberian, W Bencze, B Clarke, A Al-Jadaan, G M Keiser, J A Kozaczuk, M Al-Meshari, B Muhlfelder, M Salomon, D I Santiago, B Al-Suwaidan, J P Turneaure and J Wade

- 224020 OPEN ACCESS —Gravity Probe B data analysis: III. Estimation tools and analysis results. J W Conklin, M I Heifetz, T Holmes, M Al-Meshari, B W Parkinson, A S Silbergleit, C W F Everitt, A Al-Jaadan, G M Keiser, B Muhlfelder, V G Solomonik and H Al-Jabreen

- 224021 — VLBI for Gravity Probe B: the guide star, IM Pegasi. N Bartel, M F Bietenholz, D E Lebach, R R Ransom, M I Ratner and I I Shapiro

For more information:

Stanford's Gravity Probe B Website

Institute of Physics, Classical and Quantum Gravity Journal Website

HEPL News Story on Gravity Probe B Final Results Announcement at NASA Headquarters, 4 May 2011

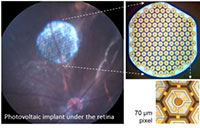

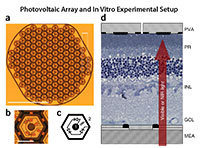

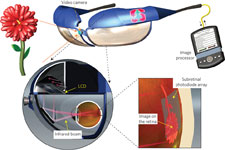

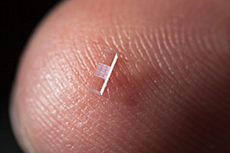

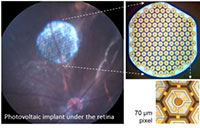

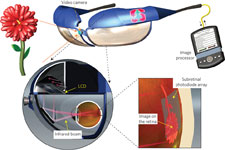

The wireless retinal implants convert

light

transmitted from special glasses

into

electrical current, stimulating

the retina's

bipolar cells. (Click to view

full size.)

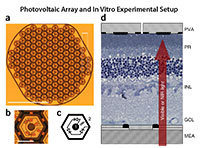

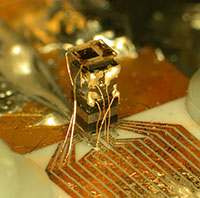

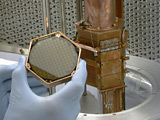

a) Photo of a single photovoltaic prosthesis

module; b) Close-up photograph

of a 70μm

wide pixel;

c)

Wiring diagram for each pixel;

d) Schematic representation of

implant in a

healthy rat. (Click to

view full size.)

Schematic diagram of the photovoltaic

retinal prosthesis (Click to view full size.)

View 90-second YouTube video describing

the

photovoltaic retinal prostheisis.

All images and video courtesy of The

Palanker Group.

April 27, 2015 — Photovoltaic retinal implant developed by HEPL's Palanker Group, could restore functional sight

So far, the Palanker Group researchers have tested the device only in animals, but a clinical trial is planned next year in France.

Story by Becky Bach, Digital Media Specialist, Stanford Medical School Office of Communications & Public Affairs

A multidisciplinary Stanford/HEPL research team, led by Professor Daniel Palanker, has developed a wireless retinal implant that they say could restore vision five times better than existing devices.

Results in rat studies suggest it could provide functional vision to patients with retinal degenerative diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa or macular degeneration.

A paper describing the implant was published online April 27 in Nature Medicine.

“The performance we’re observing at the moment is very encouraging,” said Georges Goetz, a lead author of the paper and graduate student in electrical engineering at Stanford. “Based on our current results, we hope that human recipients of this implant will be able to recognize objects and move about.”

Retinal degenerative diseases destroy photoreceptors — the retina’s rods and cones — but other parts of the eye usually remain healthy. The implant capitalizes on the electrical excitability of retinal neurons known as bipolar cells. These cells process the photoreceptors’ inputs before they reach ganglion cells, which send retinal signals to the brain. By stimulating bipolar cells, the implant takes advantage of important natural properties of the retinal neural network, which produces more refined images than the devices that skip these cells.

Made of silicon, the implant is composed of hexagonal photovoltaic pixels that convert light transmitted from special glasses worn by the recipient into electrical current. These electrical pulses then stimulate the retina’s bipolar cells, triggering a neural cascade that reaches the brain.

Clinical trial planned

So far, the team has tested the device only in animals, but a clinical trial is planned next year in France, in collaboration with a French company called Pixium Vision, said Daniel Palanker, PhD, professor of ophthalmology and a senior author of the paper. Initially, patients blinded by a genetic disease called retinitis pigmentosa will be included in the study.

Existing retinal prostheses are powered by extraocular devices wired to the retinal electrode array, which require complex surgeries, and provide visual acuity up to about 20/1,200. This new photovoltaic implant could be a big improvement because its small size, modularity and lack of wires enable a minimally invasive surgery. Vision tests in rats have shown it restores visual acuity to an equivalent of 20/250.

Next, Palanker and his team plan to further improve acuity by developing chips with smaller pixels. To ensure the signals reach the target neurons, they plan to add a tiny prong to each electrode that will protrude into the target cell layer.

“Eventually, we hope this technology will restore vision of 20/120,” Palanker said. “And if it works that well, it will become relevant to patients with age-related macular degeneration.”

Henri Lorach, PhD, a Stanford research associate, is the other lead author, and Alexander Sher, PhD, assistant professor of physics at the University of California-Santa Cruz, is the other senior author.

Other Stanford co-authors are Xin Lei, graduate student in electrical engineering; Theodore Kamins, PhD, consulting professor of electrical engineering; Philip Huie, PhD, senior research associate; and James Harris, PhD, professor of electrical engineering.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01EY018608), the Department of Defense, the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR025744), the Stanford Spectrum fund, la Fondation Voir et Entendre and Pixium Vision.

Information about the Department of Ophthalmology, which also supported the work, is available at http://ophthalmology.stanford.edu/.

For More Information

Photovoltaic restoration of sight with high visual acuity. Nature Medicine Article by Henri Lorach, Georges Goetz, Richard Smith, Xin Lei, Yossi Mandel, Theodore Kamins, Keith Mathieson, Philip Huie, James Harris, Alexander Sher & Daniel Palanker. Nature Medicine 21, 476–482 (2015) doi:10.1038/nm.3851 Published online 27 April 2015

Stanford Medicine News Release on the Photovoltaic Retinal Prosthesis, April 27, 2015

Restoring sight to the blind with a new photovoltaic retinal prosthesis. HEPL News Story, May 13, 2012

The Palanker Group: Photovoltaic Retinal Prosthesis for Restoring Sight to the Blind

NASA Illustration.

A new program in the search for life

beyond our solar system will involve

Stanford, UC Berkeley and NASA and

will call on the skills of scientists

researching life on Earth, other

planets in our solar system,

and worlds that orbit other stars.

April 27, 2015 — Stanford and UC Berkeley partner on NASA's new effort to detect life on other planets

A new interdisciplinary research program from NASA brings together a team of scientists, including Stanford's Bruce Macintosh, to devise new technologies and techniques for detecting life on exoplanets.

(Story by Bjorn Carey. Reprinted from Stanford Report, April 27, 2015)

The study of exoplanets – planets around other stars – is a relatively new field, but planet-hunting efforts have been prolific. The discovery of the first exoplanet around a star like our sun was made in 1995, and NASA's Kepler space telescope has detected more than 1,000 exoplanets in the past six years.

Now a new NASA initiative aims to answer the big question: Is there life on these alien worlds? The NExSS (Nexus for Exoplanet System Science) initiative will bring together the "best and brightest," according to a NASA press release. NExSS will marshal the expertise of 10 universities, three NASA centers and two research institutes.

The program aims to better understand the various components of an exoplanet, as well as how the parent stars and neighboring planets might interact to support life. The program brings together planetary scientists, Earth scientists, heliophysicists and astronomers to identify and search for biosignatures, or signs of life.

"This interdisciplinary endeavor connects top research teams and provides a synthesized approach in the search for planets with the greatest potential for signs of life," said Jim Green, NASA’s director of planetary science. "The hunt for exoplanets is not only a priority for astronomers, it’s of keen interest to planetary and climate scientists as well."

One NExSS project, called "Exoplanets Unveiled," will specifically address this question: What are the properties of exoplanetary systems, particularly as they relate to their formation, evolution and potential to harbor life? The project is led by James Graham, a professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, and will draw upon the expertise of Bruce Macintosh, a professor of physics at Stanford and the principal investigator for the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI).

GPI, a new instrument for the Gemini Observatory, began its exoplanet survey at the Gemini South Telescope in November 2014. Most exoplanets are detected through the Doppler technique – measuring the "wobble" of the parent star as an unseen planet’s gravity tugs on it – or though detection of a transit, as the planet’s orbit brings it between the star and Earth.

As the newest generation of instruments for imaging exoplanets, GPI blocks out the bright star to directly see the faint planet next door. GPI has already imaged two previously known exoplanets and disks of planetary debris orbiting young stars where planets recently formed.

"Getting a complete picture of all the incredibly strange planetary systems out there will require every different technique," Macintosh said. "With this new collaboration, we will combine the strengths of imaging, Doppler and transits to characterize planets and their orbits."

The first image of an Earth-size exoplanet is still likely years away. GPI is currently only sensitive enough to detect infrared emission from hot, bright planets the size of Jupiter. Detecting the faint, reflected light of cooler, smaller planets will require next-generation technologies and techniques, which MacIntosh said will be developed via instruments like GPI for eventual use on future planet-finding missions such as NASA's Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST).

"If you could see reflected light, you might be able to see the signature of life," said Paul Kalas, an adjunct professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley and co-primary investigator for the project. "We are just now sowing the seeds to get to that point."

For More Information

Stanford and UC Berkeley partner on NASA's new effort to detect life on other planets by Bjorn Carrey, Stanford Report, April 27, 2015

Professor Bruce Macintosh — Stanford Physics Department Web Page

New planet-hunting camera produces best-ever image of an alien planet, says Stanford physicist. Stanford News Story by Bjorn Carey, May 16, 2014.

Gemni Planet Imager Website

Berkeley Nexus for Exoplanet System Science Website

Image of a solar flare, captured

on 12 Jan 2015 by NASA's Solar

Dynamics Observatory (SDO).

Image Credit: NASA/SDO

and the

AIA,

EVE and HMI Science Teams

View a 20-minute silent video overview

of solar physics and the Stanford

Solar Observatories Group's HMI

(Helioseismic & Magnetic Imager)

January 14, 2015— Artificial Intelligence Helps Stanford Physicists Predict Dangerous Solar Flares

Though scientists do not completely understand what triggers solar flares, Stanford solar physicists Monica Bobra and Sebastien Couvidat have automated the analysis of those gigantic explosions. The method could someday provide advance warning to protect power grids and communication satellites.

Story by Leslie Willoughby. Reprinted from the Stanford Report, January 14, 2015

Solar flares can release the energy equivalent of many atomic bombs, enough to cut out satellite communications and damage power grids on Earth, 93 million miles away. The flares arise from twisted magnetic fields that occur all over the sun's surface, and they increase in frequency every 11 years, a cycle that is now at its maximum.

Using artificial intelligence techniques, Stanford solar physicists Monica Bobra and Sebastien Couvidat have automated the analysis of the largest ever set of solar observations to forecast solar flares using data from the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which takes more data than any other satellite in NASA history. Their study identifies which features are most useful for predicting solar flares.

Specifically, their study required analyzing vector magnetic field data. Historically, instruments measured the line-of-sight component of the solar magnetic field, an approach that showed only the amplitude of the field. Later, instruments showed the strength and direction of the fields, called vector magnetic fields, but for only a small part of the sun, or part of the time. Now an instrument on a satellite-based system, the Helioseismic Magnetic Imager (HMI) aboard SDO, collects vector magnetic fields and other observations of the entire sun almost continuously.

Adding machine learning

The Stanford Solar Observatories Group, headed by physics Professor Phil Scherrer, processes and stores the SDO data, which takes 1.5 terabytes of data a day. During a recent afternoon tea break, Bobra and Couvidat chatted about what they might do with all that data and talked about trying something different.

They recognized the difficulty of forming predictions when using pure theory and they had heard of the popularity of the online class on machine learning taught by Andrew Ng, a Stanford professor of computer science.

"Machine learning is a sophisticated way to analyze a ton of data and classify it into different groups," Bobra said.

Machine learning software ascribes information to a set of established categories. The software looks for patterns and tries to see which information is relevant for predicting a particular category.

For example, one could use machine-learning software to predict whether or not people are fast swimmers. First, the software looks at features of swimmers – for example, their heights, weights, dietary habits, sleeping habits, their dogs' names and their dates of birth.

And then, through a guess and check strategy, the software would try to identify which information is useful in predicting whether or not a swimmer is particularly speedy. It could look at a swimmer's height and guess whether that particular height lies within the height range of speedy swimmers, yes or no. If it guessed correctly, it would "learn" that the height might be a good predictor of speed.

The software might find that a swimmer's sleeping habits are good predictors of speed, whereas the name of the swimmer's dog is not.

The predictions would not be very accurate after analysis of just the first few swimmers. The more information provided, the better machine learning gets at predicting.

Similarly, the researchers wanted to know how successfully machine learning would predict the strength of solar flares from information about sunspots.

"We had never worked with the machine learning algorithm before, but after we took the course we thought it would be a good idea to apply it to solar flare forecasting," Couvidat said. He and Bobra applied the algorithms and characterized the features of the two strongest classes of solar flares, M and X. Though others have used machine learning algorithms to predict solar flares, nobody has done it with such a large set of data and or with vector magnetic field observations.

M-class flares can cause minor radiation storms that might endanger astronauts and cause brief radio blackouts at Earth's poles. X-class flares are the most powerful.

Better flare prediction

The researchers catalogued flaring and non-flaring regions from a database of more than 2,000 active regions and then characterized those regions by 25 features such as energy, current and field gradient. They then fed the learning machine 70 percent of the data, to train it to identify relevant features. And then they used the machine to analyze the remaining 30 percent of the data to test its accuracy in predicting solar flares.

Machine learning confirmed that the topology of the magnetic field and the energy stored in the magnetic field are very relevant to predicting solar flares. Using just a few of the 25 features, machine learning discriminated between active regions that would flare and those that would not flare. Although others have used different methods to come up with similar results, machine learning provides a significant improvement because automated analysis is faster and could provide earlier warnings of solar flares.

However, this study only used information from the solar surface. That would be like trying to predict Earth's weather from only surface measurements like temperature, without considering the wind and cloud cover. The next step in solar flare prediction would be to incorporate data from the sun's atmosphere, Bobra said.

Doing so would allow Bobra to pursue her passion for solar physics. "It's exciting because we not only have a ton of data, but the images are just so beautiful," she said. "And it's truly universal. Creatures from a different galaxy could be learning these same principles."

Monica Bobra and Sebastien Couvidat worked under the direction of physicist Phil Scherrer of the WW Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory at Stanford.

Leslie Willoughby is an intern at the Stanford News Service.

For More Information

Stanford Solar Physics/Observatories Group Website—http://sun.stanford.edu

NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) website

NASA Living With A Star Program

NASA SDO: StanfordHelioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) Website

NASA SDO: Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) Website

NASA SDO: Extreme Ultraviolet Variability Experiment (EVE) Website

Left: HEPL doctoral candidate, Karthik

Balakrishnan

holds a spherical proof

mass from his UV-LED charge control

experiment in the lab. Right: A Russian-

Ukranian Dnepr rocket launches

Karthik's experiment, housed in a Saudi

Arabian satellite, into orbit.

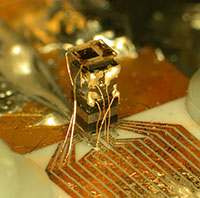

Given the current political state of the world, you might think that the headline above describes a doctoral candidate’s pipe dream. However, back on June 19, 2014, this satellite launch event actually happened!

Karthik Balakrishnan is a doctoral student in the Aeronautics and Astronautics Department of Stanford’s School of Engineering. His research on charge control systems for satellite guidance is sponsored by HEPL and the Center for Excellence in Aeronautics and Astronautics (a collaboration between Stanford and the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia), and it is being carried out in the laboratory of Robert Byer, Professor of Lasers and Optics in Stanford’s Department of Applied Physics. Professor Byer is also a former director of HEPL. Mr. Balakrishnan’s experimental apparatus uses low-power, ultraviolet frequency LEDs to remove electrostatic charge buildup from a baseball-sized, gold-coated sphere comprising the guidance control mechanism that enables a satellite to circle the Earth (or another planet or the Sun) as a gravitational reference sensor (GRS). Read Full Story...

March 17, 2014 — New Evidence from Space Supports Stanford Physicist's Theory of How the Universe Began

The detection of gravitational waves by the BICEP2 experiment at the South Pole supports the cosmic inflation theory of how the universe came to be. The discovery, made in part by Assistant Professor Chao-Lin Kuo, supports the theoretical work of Stanford's Andrei Linde.

(Story by Bjorn Carey. Reprinted from Stanford Report, March 17, 2014)

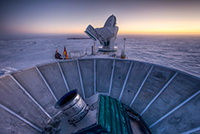

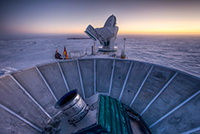

BICEP2 telescope (foreground) and

the South Pole Telescope

( background). Photo: Steffen Richter,

Harvard University

Stanford physicist, Andre Linde and his

wife, receive the news of data confirming

Linde's theory of cosmic inflaction from

Chao-Lin Kuo, Assistant Professor of

Physics at HEPL and SLAC.

Video by Kurt Hickman

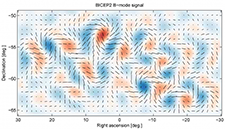

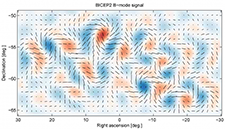

The signature of primordial gravitational

waves, as seen in the cosmic microwave

background in the image, are twisting

patterns known as B-mode polarization.

(Image Credit: BICEP2 Project)

Almost 14 billion years ago, the universe we inhabit burst into existence in an extraordinary event that initiated the Big Bang. In the first fleeting fraction of a second, the universe expanded exponentially, stretching far beyond the view of today's best telescopes. All this, of course, has just been theory.

Researchers from the BICEP2 collaboration today announced the first direct evidence supporting this theory, known as "cosmic inflation." Their data also represent the first images of gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time. These waves have been described as the "first tremors of the Big Bang." Finally, the data confirm a deep connection between quantum mechanics and general relativity.

"This is really exciting. We have made the first direct image of gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time across the primordial sky, and verified a theory about the creation of the whole universe," said Chao-Lin Kuo, an assistant professor of physics at Stanford and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and a co-leader of the BICEP2 collaboration.