1. Rock, Paper, Scissors

In 1997, a computer named Deep Blue beat world chess champion Gary Kasparov at a game of chess. In 2023, IBM has finally gained the confidence to expand its repertoire of human vs. computer games and enlisted you to write a program that allows a human player and computer to spar over a game of Rock Paper Scissors.

Each game consists of 5 rounds of Rock, Paper, Scissors. Each round consists of you - the user - choosing whether to play Rock, Paper or Scissors, and the computer doing the same. In this game, the user will type 1 if they wish to play Rock, 2 if they wish to play Paper, and 3 if they wish to play Scissors.

In each round, you should do the following:

- Prompt the user to enter their move (you can assume they type '1', '2' or '3'.)

- Randomly choose either rock, paper, or scissors as the computer's move using the random module (remember, calling

random.randint(a, b)will give you back an integer between a and b, inclusive). - Determine who wins the round. As a reminder, rock beats scissors, scissors beats paper, and paper, somewhat inexplicably, beats rock.

- Print a message reporting whether the human player won or lost and which moves each player made.

At the end of the program, you should print a message saying how many rounds the user won.

Here's a sample run, where the user's input appears after "Your move (1, 2, or 3): ". Remember that this is a random program, so if you run your code, you might see different results in each match.

Your move (1, 2, or 3): 1

It's a tie!

Your move (1, 2, or 3): 3

You win! Scissors cuts paper

Your move (1, 2, or 3): 2

You lose! Scissors cuts paper

Your move (1, 2, or 3): 2

It's a tie!

Your move (1, 2, or 3): 1

You win! Rock crushes scissors

You won 2 rounds!

import random

NUM_ROUNDS = 5

def main():

num_human_wins = 0

for i in range(NUM_ROUNDS):

user_choice = int(input("Your move (1, 2, or 3): "))

computer_choice = random.randint(1, 3)

if computer_choice == user_choice:

print("It's a tie!")

else:

if user_choice == 1:

if computer_choice == 3:

print("You win! Rock crushes scissors")

num_human_wins += 1

else:

print("You lose! Paper covers rock")

if user_choice == 3:

if computer_choice == 2:

print("You win! Scissors cuts paper")

num_human_wins += 1

else:

print("You lose! Rock crushes scissors")

if user_choice == 2:

if computer_choice == 1:

print("You win! Paper covers rock")

num_human_wins += 1

else:

print("You lose! Scissors cuts paper")

print("You won " + str(num_human_wins) + " rounds!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

2. Estimating Pi

Write a program that estimates the value of pi using Python!

π is a mathematical constant that comes from geometric properties of a circle. Specifically, a circle that has radius r will have area (πr^2) and circumference (2πr). π's value is roughly 3.14, and in this problem, we'll get pretty close to that value (we're shooting for 2 decimal places of accuracy)!

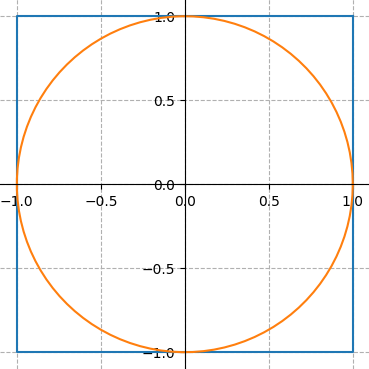

One nice way to estimate π is using the random module. Imagine a 2x2 square drawn on a 2D plane, centered at the origin. We can draw a circle inside this square, with radius 1, centered at the origin. So far, our drawing looks like this:

The area of the square is 2 x 2 = 4 and the area of the circle is π x 1^2 = π. The circle takes up a large fraction of the square's area: to be precise, the ratio of the circle's area to the square's area is π/4.

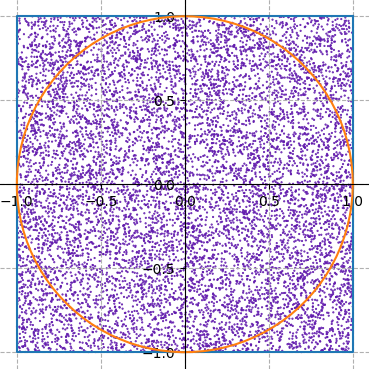

One way to think about this is that if you pick a bunch of points, randomly, inside the square, the fraction of those points that will lie inside the circle is π/4.

Your program should randomly pick 100000 points inside the square (remember that it's good programming style to use constants where appropriate; consider defining a constant NUM_POINTS = 100000).

You can pick a random point in the square by picking a random x-coordinate and a random y-coordinate (both of which should be real numbers between -1 and 1). Count the number of points that are inside the circle and use that number to calculate the fraction of points that landed inside the circle. That number is approximately π/4, so multiply your ratio by 4 and print out that value as our approximation of π. How close did you get? What happens when you change NUM_POINTS?

Hint: A point (x, y) is inside the circle of radius 1, centered at the origin, if (x^2 + y^2 <= 1).

Note: Your function will produce a number, not the graphs that you see in this writeup. However, these graphs were actually generated using Python and you now have the skills to make images like these!

import random

NUM_POINTS = 100_000

def main():

"""

Estimates the value of π by randomly choosing points in the square and

calculating the percentage of points that lie in the circle. Prints out

the estimated value of π.

"""

num_in_circle = 0 # Counter variable

for i in range(NUM_POINTS):

"""

Pick a random point in the square. To do this, we need to pick a random

x coordinate and random y coordinate, each in the interval [-1, 1].

"""

x = random.uniform(-1, 1)

y = random.uniform(-1, 1)

"""

The formula for a circle is x^2 + y^2 = r^2. In this case, since the

circle has radius 1, it can be described by x^2 + y^2 = 1. Points that

lie *inside* the circle have x^2 + y^2 <= 1.

"""

if x ** 2 + y ** 2 <= 1:

# (x, y) is inside the circle

num_in_circle += 1

"""

The area of the square is 4, the area of the circle is π. Thus, the

percentage of points in the circle is approximately π / 4.

"""

percent_in_circle = num_in_circle / NUM_POINTS # ~ π / 4

π = percent_in_circle * 4

print("π is roughly " + str(π))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

3. Interesting Lists

Write a function make_interesting(num_list) that accepts a list of integers and returns a new list based on the given list. The new list should have each of the values in num_list as follows: if the integer in num_list is less than zero, the new list should not have this value; if the integer in num_list is greater than or equal to zero and odd, the new list should have this integer value with 10 added to it; if the integer in num_list is greater than or equal to zero and even, the new list should have this integer value unchanged. We'll consider the number 0 to be even.

Here are some sample calls to make_interesting and what should be returned.

>>> make_interesting([-2, 33, 14, 6, -13, 9, 2])

[43, 14, 6, 19, 2]

>>> make_interesting([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

[11, 2, 13, 4, 15]

>>> make_interesting([-10, -20, -5])

[]

def make_interesting(num_list):

result = []

for value in num_list:

if value >= 0:

if (value % 2) == 1: # Check if value is odd

result.append(value * 10)

else:

result.append(value)

return result

4. Rotate

Write a function rotate_list_right(numbers, n) that returns a "rotated" version of a list of integers numbers. You should rotate numbers to the right n times, so that each element in lst is shifted forward n places, and the last n elements are moved to the start of the list. Your function should not change the list that is passed as a parameter, but instead return a new list.

>>> rotate_list_right([1, 2, 3, 4, 5], 2)

[4, 5, 1, 2, 3]

>>> rotate_list_right([5, 3, 3, 1], 1)

[1, 5, 3, 3]

def rotate_list_right(numbers, n):

output_list = []

for i in range(len(numbers) - n, len(numbers)):

output_list.append(numbers[i])

for i in range(0, len(numbers) - n):

output_list.append(numbers[i])

return output_list

5. Average Temps

Say you're given a list of lists, where each inner list contains the average temperatures from all 12 months of a year as floats. We want to find the average temperature for each year, and form a list of these annual averages.

Implement the function annual_temps(nested) that takes in a nested list of monthly temperature lists, and returns a (non-nested) list of the average temperatures from each year.

For example, given the following list:

month_values = [[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12],

[3,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0],

[12,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0]]

annual_temps(nested) should return:

[6.5,

0.25,

1.0]

def annual_temps(nested):

result = []

for lst in nested:

total = 0

for temp in lst:

total += temp

avg = total / 12

result.append(avg)

return result

6. Fireworks

We often think of lists of lists as 2D grids, since they've got two dimensions that we can index into. We can refer to locations within our lists of lists as coordinates with an x and y value. For example, if we had a grid like this:

grid = [[None, None, None],

[None, None, None],

[None, 'f' , None],

[None, None, None]]

We could access the 'f' in this grid by doing grid[2][1], where we think of 2 as the y-coordinate, and 1 as the x-coordinate.

In this problem we'll use a list of lists to represent a scene with certain physical properties (just like in Sand). Say that each location in our list of lists, or grid, can either contain a firework represented by 'f', a sparkle represented by 's', or None. We want to loop over every location in our grid and make any fireworks "explode", turning the 'f' at that location to None, and putting a sparkle 's' to the left, right, top, and bottom of that x, y location. For example, after exploding, the grid above should look like:

[[None, None, None],

[None, 's' , None],

['s' , None, 's' ],

[None, 's' , None]]

Write a function explode_firewords(grid) that takes in a list of lists grid and loops over the coordinates of that grid, exploding any fireworks. You can assume that the fireworks are spaced so that no sparkles will overlap. If a firework is placed on the edge of the grid, so that some of its sparkles would go beyond the bounds of the grid, don't draw any sparkles in locations that are out of bounds.

Here's another example of a grid before and after calling your function explode_fireworks.

# before

[[None, 'f' , None, None, None],

[None, None, None, None, 'f' ],

[None, None, None, None, None],

[None, 'f' , None, None, None]]

# after

[['s' , None, 's' , None, 's' ],

[None, 's' , None, 's' , None],

[None, 's' , None, None, 's' ],

['s' , None, 's' , None, None]]

def explode(grid, x, y):

"""

Helper function, explodes the firework at

location x, y

"""

grid[y][x] = None

if x > 0:

grid[y][x-1] = "s"

if x < len(grid[0]) - 1:

grid[y][x+1] = "s"

if y > 0:

grid[y-1][x] = "s"

if y < len(grid) - 1:

grid[y+1][x] = "s"

def explode_fireworks(grid):

for y in range(len(grid)):

for x in range(len(grid[0])):

if grid[y][x] == "f":

explode(grid, x, y)

return grid

7. Password Maker

Write the function make_password(s) that takes in a string s and makes it into a password by replacing common letters with similar looking special characters. Any a's should become @'s, i's should become !'s, and o's should become 0's. This should be case-insensitive, meaning that the uppercase versions of these letters should also be converted to their special characters. However, make sure that any other characters that were originally uppercase stay uppercase in the returned value.

Here are a few sample calls of this function:

>>> make_password('HI!')

'H!!'

>>> make_password('this is a good password')

'th!s !s @ g00d p@ssw0rd'

def make_password(s):

result = ""

for char in s:

low = char.lower()

if low == "a":

result += "@"

elif low == "i":

result += "!"

elif low == "o":

result += "0"

else:

result += char

return result

8. Grade Boost

Let's say that the CS106A instructors have randomly decided to give a 5-point bonus to students whose names begin with a certain letter. They've stored the test scores of every student in a dictionary, where the keys are student names, and the values are the scores that the student earned. For example:

students = {

'Elyse': 5,

'Chris': 20,

'Mehran': 20,

'Clinton': 40,

'Neel': 12

}

If the instructors choose to boost students whose names started with the letter 'C', this dictionary would become:

students = {

'Elyse': 5,

'Chris': 25,

'Mehran': 20,

'Clinton': 45,

'Neel': 12

}

Write a function grade_boost(students, letter), which takes in a dictionary of students like the one shown above and a letter indicating which students' names to boost, and updates the students dictionary to boost the corresponding grades by 5 points. You can assume the given letter will be uppercase, and all student names will start with an uppercase letter.

A sample call of the function is shown below:

>>> grade_boost({'Elyse': 5, 'Chris': 20, 'Mehran': 20, 'Clinton': 40, 'Neel': 12}, 'C')

{'Elyse': 5, 'Chris': 25, 'Mehran': 20, 'Clinton': 45, 'Neel': 12}

>>> grade_boost({'Student1': 10, 'Student2': 15}, 'F')

{'Student1': 10, 'Student2': 15}

def grade_boost(students, letter):

for student in students:

if student[0] == letter:

students[student] += 5

return students

9. Animal Counts

Let's say we had everyone in class vote on their favorite animals by entering an animal name into an online poll. The results were then put into a file so that each line of the file is an animal name and the number of votes it received. Here some some of the results:

Dog: 34

Bird: 20

cat: 14

Elephant: 7

dog: 5

CAT: 2

What we want to do is to read in the data from this file into a dictionary where the key is the animal name (string) and the value is the number of votes this animal got (integer).

Unfortunately, the polling mechanism didn't take into account that some people would capitalize the names of animals differently. Notice that above, “Dog” and “dog” each get their own score, but really we'd like to sum all the votes for each animal name in a case-insensitive way, so that we see that 39 people have “dog” as their favorite animal.

Your task is to write a helper function get_animal_counts(filename) that takes in a filename and returns a dictionary with the duplicate counts (for keys with the same characters but different capitalization) combined. The new keys should be all lowercase. Calling our helper function with the file above would return:

{

'dog': 39,

'bird': 20,

'cat': 16,

'elephant': 7

}

def get_animal_counts(filename):

counts = {}

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

line = line.strip()

parts = line.split(":")

animal = parts[0].lower()

count = int(parts[1])

if animal not in counts:

counts[animal] = count

else:

counts[animal] += count

return counts

10. List2Dict

Say you wanted to store your friends' phone numbers using Python, but you did so before learning about dictionaries. Right now, you've got a big list of your friends' names (as strings), followed by their phone numbers (also as strings). You realize now that you'd much rather store this information as a nested dictionary, where the keys are names, and the values are lists of phone numbers.

You have a list that might look something like this:

['Noah', '1234567', 'Anooshree', '2347891', '9371924', 'Mel', '2398712']

But you'd like to turn it into:

{

'Noah': ['1234567'],

'Anooshree': ['2347891', '9371924'],

'Mel': ['2398712']

}

Write a function list_to_dict(friends_lst) that takes in a list of friend names and numbers, and converts it to a nested dictionary as described above. You can assume that a phone number belongs to the name that precedes it.

Hint: You might check whether an element in the list is a name or number using the .isalpha() or .isdigit() function.

def list_to_dict(friends_lst):

friends_dict = {}

curr_friend = ""

for elem in friends_lst:

if elem.isalpha():

curr_friend = elem

friends_dict[curr_friend] = []

else:

friends_dict[curr_friend].append(elem)

return friends_dict

12. Finding Grandchildren

Implement a function find_grandchildren(parents_to_children), which is given the dictionary parents_to_children whose keys are strings representing parent names and whose values are lists of that parent's children's names. Create and return a dictionary from people's names to lists of those people's grandchildren's names.

For example, given this dictionary:

parents_to_children = {

'Khaled': ['Chibundu', 'Jesmyn'],

'Daniel': ['Khaled', 'Eve'],

'Jesmyn': ['Frank'],

'Eve': ['Grace']

}

Daniel's grandchildren are Chibundu, Jesmyn, and Grace, since those are the children of his children. Additionally, Khaled is Frank's grandparent, since Frank's parent is Khaled's child. Therefore, calling find_grandchildren(parents_to_children) returns this dictionary:

{

'Khaled': ['Frank'],

'Daniel': ['Chibundu', 'Jesmyn', 'Grace']

}

Note that the people who aren't grandparents don't show up as keys in the new dictionary. Depending on the way your process the dictionary, the order of your results may be different, but you should have the same keys and values.

def find_grandchildren(parents_to_children):

result = {}

for parent in parents_to_children:

all_grandchildren = []

# get a list of this person's children

children = parents_to_children[parent]

# check if each child has any children themselves

for child in children:

if child in parents_to_children:

# if so, add each child as a grandchild

grandchildren = parents_to_children[child]

for grandchild in grandchildren:

all_grandchildren.append(grandchild)

# only add to result dict if there were grandchildren

if len(all_grandchildren) > 0:

result[parent] = all_grandchildren

return result

13. Class Class

No, that's not a typo. We're going to implement a class that stores information about students enrolled in a class at Stanford. Specifically, your Class class will have the following methods:

-

init(self)- initializes a newClassinstance and any member variables -

add_student(self, name, id)- adds a student by name (string) and id (int) to the class -

get_id(self, name)- returns the id of the student with this name, or -1 if this student isn't in the class -

get_class_list(self)- returns a list of the names of all students enrolled in the class

Here's how your class might be used from another program.

def main():

cs106a = Class()

cs106a.add_student("Muhammad", 12345678)

print(cs106a.get_class_list()) # prints ["Muhammad"]

cs106a.add_student("Elyse", 56781234)

print(cs106a.get_class_list()) # prints ["Muhammad", "Elyse"]

print(cs106a.get_id("Maria")) # prints -1

print(cs106a.get_id("Muhammad")) # prints 12345678

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Here's your starter code:

# File: Class.py

class Class:

def __init__(self):

"""

Creates a new instance of the Class class

"""

pass

def add_student(self, name, id):

"""

Adds a student by name (string) and id (int) to the class

"""

pass

def get_id(self, name):

"""

Returns the id of the student with this name, or -1 if this

student isn't in the class

"""

pass

def get_catalog(self):

"""

Returns a list of the names of all students enrolled in

the class

"""

pass

class Class:

def __init__(self):

"""

Creates a new instance of the Class class

"""

self.students = {} # instance variable to keep track of the student/id pairs

def add_student(self, name, id):

"""

Adds a student by name (string) and id (int) to the class

"""

self.students[name] = id

def get_id(self, name):

"""

Returns the id of the student with this name, or -1 if this

student isn't in the class

"""

if name in self.students:

return self.students[name]

return -1

def get_class_list(self):

"""

Returns a list of the names of all students enrolled in the class

"""

student_lst = []

for student in self.students:

student_lst.append(student)

return student_lst

14. Pizza Class

Implement a class Pizza that represents a pizza pie with the following methods:

-

init(self)- initializes a new Pizza instance with 8 slices and no toppings, creating any member variables you'd like -

take_slice(self)- removes one slice of pizza, or prints "no slices left" if there are 0 slices left -

get_topping_list(self)- returns a list of all toppings currently on the pizza -

add_topping(self, topping)- adds the topping (which is a string) to the pizza, so that all future calls to get_topping_list include this topping

Here's how your class might be used from another program.

from pizza import Pizza

def main():

veggie = Pizza()

print(veggie.get_topping_list()) # prints []

veggie.add_topping("green peppers")

veggie.add_topping("mushrooms")

for i in range(8):

veggie.take_slice()

print(veggie.get_topping_list()) # ["green peppers", "mushrooms"]

veggie.take_slice() # prints No slices left

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Here's your starter code:

# File: class.py

class Pizza:

def __init__(self):

"""

Creates a new instance of the Pizza class

"""

pass

def take_slice(self):

"""

Takes a slice from the pizza, reducing its number of slices by 1

"""

pass

def get_topping_list(self):

"""

Returns a list of all toppings currently on the pizza

"""

pass

def add_topping(self, topping):

"""

Adds the topping (which is a string) to the pizza, so that all future

calls to get_topping_list include this topping

"""

pass

# File: pizza.py

class Pizza:

def __init__(self):

"""

Creates a new instance of the Pizza class

"""

self.num_slices = 8

self.toppings = []

def take_slice(self):

"""

Takes a slice from the pizza, reducing its number of slices by 1

"""

if self.num_slices > 0:

self.num_slices -= 1

else:

print('No slices left')

def get_topping_list(self):

"""

Returns a list of all toppings currently on the pizza

"""

return self.toppings

def add_topping(self, topping):

"""

Adds the topping (which is a string) to the pizza, so that all future

calls to get_topping_list include this topping

"""

self.toppings.append(topping)

15. Sorting Houses

Given a list of tuples that represent houses for rent, the number of bedrooms, and their prices, like so:

houses = [('main st.', 4, 4000), ('elm st.', 1, 1200), ('pine st.', 2, 1600)]

Sort the list in the following ways:

- In ascending order by number of rooms

- In descending order of price

- In ascending order of price-per-room

def num_rooms(tup):

return tup[1]

def price(tup):

return tup[2]

def price_per_room(tup):

return tup[2]/tup[1]

houses = [('main st.', 4, 4000), ('elm st.', 1, 1200), ('pine st.', 2, 1600)]

# In ascending order by number of rooms

print(sorted(houses, key=num_rooms))

# In descending order of price

print(sorted(houses, key=price, reverse=True))

# In ascending order of price-per-room

print(sorted(houses, key=price_per_room))