Assign4: Merge

Binary merge

The binary merge operation is a very common operation in computer science, where two individual sorted sequences are merged into one larger sorted sequence. This operation serves as the backbone of many different sorting algorithms (some of which we will explore later in the course), which themselves are used in a broad diversity of programs and applications. In that way, the binary merge is the hardworking worker bee at the core of many interesting algorithms and applications!

Your first task is to write the function

Queue<int> merge(Queue<int> one, Queue<int> two)

that performs a binary merge.

- The elements of Queues

oneandtwoare expected to be in increasing order from front to back. The returned result is a Queue containing all elements fromoneandtwoin increasing order from front to back. - The two Queues are not required to be the same length. One could be be enormous; the other could be empty. Be sure your function handles all possibilities.

- You must implement binary merge using iteration, not recursion.

- Although it is possible and even quite elegant to solve recursively, the cost of one stack frame per element being merged is much too high to bear and would cause the function to be unable to merge larger sequences. The limit on the maximum length sequence would depend on the callstack. Review the information you gathered in the Assign3 warmup and answer the following questions in

short_answer.txt: - Q7. Give a rough estimate of the maximum length sequence that could be successfully merged on your system assuming a recursive implementation of binary merge.

- Q8. What would be the observed behavior if attempting to merge a sequence larger than that maximum?

- Although it is possible and even quite elegant to solve recursively, the cost of one stack frame per element being merged is much too high to bear and would cause the function to be unable to merge larger sequences. The limit on the maximum length sequence would depend on the callstack. Review the information you gathered in the Assign3 warmup and answer the following questions in

- Although we expect the provided queues

oneandtwoto be in sorted order, we've learned in previous assignments that making assumptions about input into functions that we write can be very dangerous – remember the stack overflow that happened when passing in a negative number into thefactorialfunction? For that reason, we are also going to require you to do some validation of the precondition assumption of this function, in which you will ensure that the provided queues are actually in sorted order. If at any point in processing the sequence you find an element which is out of order, you should raise an error with a descriptive message by calling theerrorfunction.- There are two equally valid approaches to solving this problem, and you may choose to implement either one.

- The first approach is slightly more straightforward to think about, but a little less efficient. Before starting the meat of the operation, you can inspect the contents of each of the provided queues – if either one is out of order, raise an error. If you choose this approach, we would recommend writing a helper function to handle this inspection.

- The second approach is a little more tricky to think about, but does not require an extra pass over the queues, making it a little more efficient. In this approach, you can enforce the sorted order check while completing the merge. If you ever encounter an element that seems to be misplaced when building the merged queue, raise an error. If you choose to this approach, you do not need a helper function, as the error checking will be build into the logic of the merge operation itself.

- Be sure to thoroughly test

mergebefore moving on. You will use it to implement additional operations and you want to confirm it works correctly in all situations now so you can use it later with confidence. In particular, consider writing tests that pass in queues of differing lengths, and queues that are not originally in sorted order, to make sure your error handling code works as expected.

Timing and Big O

We have added a new TIME_OPERATION(size, expression) feature to the SimpleTest framework. it allows you to do simple execution timing. It can be used like this:

PROVIDED_TEST("Time operation vector sort")

{

Vector<int> v = {3, 7, 2, 45, 2, 6, 3, 56, 12};

TIME_OPERATION(v.size(), v.sort());

}

The test results for this test will include the measured time of execution:

Time operation vector sort

Line 174 Time v.sort() (size = 9) completed in 0 secs

Timing the same operation over a range of input sizes measures the growth of the work relative to input size, i.e. the algorithm's Big O. Handy!

First predict what you expect to be the Big O of your merge function. Then use the timing operation to measure the execution time over 4 or more different sizes. For small input, the timing data is very noisy, for large inputs, it requires much patience. Experiment to find sizes in the "sweet spot" – large enough to be fairly stable but small enough to complete under a minute.

In short_answer.txt:

- Q9. Include the data from your execution timing and explain how is supports your Big O prediction for merge.

Multiway merge

A multiway merge or k-way merge is an extension of the binary merge operation, which receives k sorted lists and merges the lists into a single sorted list.

We have provided in the starter code a version of multiMerge that is built on top of your binary merge. The function is also replicated below for convenience.

Queue<int> multiMerge(Vector<Queue<int>>& all)

{

Queue<int> result;

for (Queue<int> q : all) {

result = merge(q, result);

}

return result;

}

- Assuming that you have implemented the

mergefunction from the previous step correctly, our provided code should work correctly. Run the provided tests, and confirm that the function works as expected. - The function may be asked to merge 0 lists (represented by an empty

Vector) or many empty lists (represented by aVectorof empty queues). Trace the function and predict how it would handle such input. Add test cases to confirm that the function behaves as expected in these scenarios. - First predict what you expect to be the Big O of

multiMergefunction. Then use the timing operation to measure the execution time over 4 or more different sizes. Inshort_answer.txt:- Q10. Include the data from your execution timing and explain how it supports your Big O prediction for multiMerge.

Divide and conquer to the rescue

The above implementation of multiMerge really slows down for longer sequences, since the merge operation is repeatedly applied to longer and longer sequences.

Your goal now is to write the function

Queue<int> recMultiMerge(Vector<Queue<int>>& all)

that applies the power of recursive divide-and-conquer to achieve much improved performance for multiway merge.

The strategy for recMultiMerge is as follows:

- Divide the input collection of

ksequences into two halves. The "left" half is the first K/2 sequences in the vector, and the "right" half is the rest of the sequences.- The Vector subList operation can be used to subdivide a Vector, which you may find helpful.

- Make a recursive call to

recMultiMergeon the "left" half of the sequences to generate one combined, sorted sequence. Then, do the same for the "right" half of the sequences, generating a second combined, sorted sequence. - Use your binary

mergefunction to join the two combined sequences into the final result sequence, which is then returned.

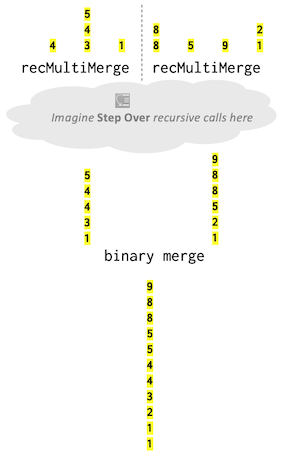

In the diagram below, we drew the contents of each queue in a vertical yellow box. The initial collection has seven sequences. The dotted line shows the division into left and right halves of 3 and 4 sequences, respectively. Each half is recursively multiway merged. The combine step calls binary merge to produce the final result.

You can prove that the runtime for recMultiMerge is O(n log k) where n is the total number of elements over all sequences and k is the count of sequences at the start of the multiway merge.

What, exactly, does O(n log k) mean? It might help to imagine that

nis allowed to vary, while k stays constant. If you have a small

value of k, then log k is also small, and as n varies you’ll get a

plot of a straight line with a small slope.

If you were to increase the value k, the slope of that line will gently to increase, but not by much because log

k grows extremely slowly. In particular, if you look at values of

k that grow exponentially quickly (say, k = 1, then 4, then 16, then 64, then 256), the slope of the lines increase by some

fixed rate.

Given an input of n elements that is entirely unsorted, we could place each element in its own sequence and call recMultiMerge on that collection of n sequences. This would make k equal to n (maximal possible value for k). The operation would run in time O(n log n). The classic mergesort algorithm uses an approach similar to this. (more on that coming up when we discuss sorting and Big O).

The elements that are already arranged in sorted sequences give a jump start to the process. The smaller the value of k, the more work has already been done and the quicker the whole process can complete. For example, if n is a million and k is 10, O(n log k) runs about 5 times faster then O(n log n).

To finish off this task:

- Write test cases that compare

recMultiMergeto the non-recursivemultiMerge. It should handle the same inputs in all the same ways, but finish the job a heck of a lot faster. - Use the timing operation to measure the execution time over 4 or more different sizes. In

short_answer.txt:- Q11. Include the data from your execution timing and explain how it supports O(n log k) behavior for recMultiMerge.

- Q12. Earlier you worked out how a recursive implementation of

mergewould limit the allowable input sequence length. Are the limits on the call stack also an issue for the recursive implementation ofrecMultiMerge? Explain why or why not.

Notes

- If you gather numerical data from the real world, it typically has lots of increasing and decreasing runs within it. For example, if you measure peak temperatures each day of the year, you’ll find that there’s a lot of increasing runs as we move from spring to autumn, and there’s a lot of decreasing runs as we move from autumn to spring. Many sorting algorithms are designed to work well in these sorts of cases. One, natural mergesort, works by splitting the input into a collection of already-increasing or already-decreasing runs, then merging those runs into one final sequences.