Assign4: Backtracking Warmup

When you encounter a bug in a program, your first instinct is often to ask something like “Why isn’t my program doing what I want it to do?”

One of the best ways to answer that question is to instead answer this other one: “What is my program doing, and why is that different than what I intended?”

The debugger is powerful tool for answering questions like these. This warmup exercise will give you practice working the debugger in the context of complex recursive problems.

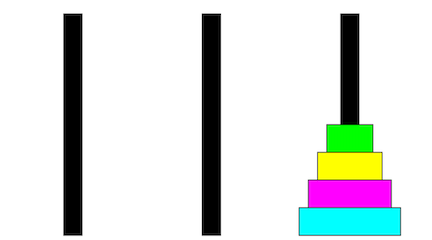

Towers of Hanoi animation

The Towers of Hanoi problem is a classic puzzle that has a beautiful recursive solution. If you haven’t yet done so, take a few minutes to read Chapter 8.1 of the textbook, which explores this problem in depth.

The warmup.cpp includes a correct solution for the Towers of Hanoi along with a charming graphical animation. Run the tests for warmup.cpp to watch the animation and marvel at how that tiny

recursive function is capable of doing so much. Isn’t that amazing?

Now let's dive into the debugger to see the mechanism of action behind all the recursive goodness.

1) Debugger Step Commands

The first part of the warmup is to explore the different types of step commands in the debugger and how that relates to tracing recursive code. The controls for stepping are on the middle toolbar of the debugger. They look like this:

The five icons from left to right are the controls for Continue, Stop, Step Over, Step Into and Step Out. If you hover your mouse over an icon, a tool tip will pop up with a label.

Set a breakpoint on the first line of the hanoiAnimation function in warmup.cpp. Run

the program in Debug mode and select the tests for the warmup.cpp file.

Step Over

When stopped at your breakpoint, find the yellow arrow pointing to a

numbered line of code in the editor pane. The program has stopped

before this line. The upper-right pane shows the numDiscs and

totalMoves variables. Because the variables have not yet been

initialized, their values are unspecified; they might be 0, or they

might be random garbage values.

First let's practice the Step Over debugger action. Each time you Step Over, one complete line is executed, including stepping "over" any function calls.

Use Step Over to advance through each line of the hanoiAnimation function:

- Step Over the initialization of

numDiscs. The Variables pane updates to show the assigned value and the yellow arrow advances to point to the subsequent line. - Step Over the call to

HanoiGui::initializeexecute the entire function that configures and displays the graphics window.- If needed, move/resize your windows so that you can see both the Qt debugger and the graphics window side by side.

- Step Over the call

pauseand you'll note a delay while the function is executing. - Step Over the

moveTowercall and the entire Hanoi animation is carried out. - After stepping to the end of

hanoiAnimation, use Continue to resume normal execution.

Question to answer in short_answer.txt:

- Q1: What is the value of the

totalMovesvariable inhanoiAnimationafter stepping over the call tomoveTower?

Step Into

Now let's practice the Step Into debugger action. Rather than stepping over function calls, Step Into goes inside the function being called so you can step through each of its statements. If the line to execute does not contain a function call, Step Into and Step Over do the same thing.

- Step Into to the call to

HanoiGui::initialize.- The editor pane switches to show the contents of the

hanoigui.cppfile and the yellow arrow is pointing to the first line of theinitializefunction. This code is unfamiliar, you didn't write it, and you didn't intend to start tracing it. - Step Out is your escape hatch. This "giant step" executes the rest of the current function up to where it returns. Step Out to return to

hanoiAnimation.

- The editor pane switches to show the contents of the

- Next up is the

pausefunction, another library function you don't want to trace through. You could step in and back out, but it's simpler to just Step Over. - You are interested in tracing the

moveTowerfunction, so Step Into to go inside. Once inside themoveTowerfunction, Step Over each line. The code should drop to the recursive case in itselsestatement. With one Step Over, the GUI window should show the entire left tower except for the bottom disc moving from the left peg to the middle peg, leaving the bottom largest disk uncovered on the left peg. This should also cause the value oftotalMovesto update containing all moves made by that recursive call.

Q2:What is the value of the totalMoves variable inside the first moveTower call after stepping over its first recursive sub-call? (In other words, just after stepping over the first recursive sub-call to moveTower inside the else statement in the recursive function.)

The next Step Over moves the bottom disk. The final Step Over moves the smaller tower on top. Use Continue to resume normal execution.

Step Out

Now let's practice the Step Out debugger action. Remove any other breakpoints, and set a breakpoint inside the base case of moveTower (on the first line of code inside its if statement). Run the program in Debug mode. When stopped at your breakpoint, use Step Out.

- Q3: After breaking at the base case of

moveTowerand then choosing Step Out, where do you end up? (What function are you in, and at what line number?) What is the value of thetotalMovesvariable at this point?

Practice with Step Into/Over/Out

Understanding the operations of the different step actions is a great way to develop your understanding of recursion and its mechanics. Re-run the program, stop in debugger again, and do some tracing and exploration of your own. Watch the animated discs and consider how this relates to the sequence of recursive calls. Observe how stack frames are added and removed from the debugger call stack. Select different levels on the call stack to see the value of the parameters in the upper-right pane and the nesting of recursive calls. Here are some suggestions for how stepping can help:

- Step Over a recursive call is useful when thinking holistically. A recursive call is simply a "magic" black box that completely handles the smaller subproblem.

- Step Into a recursive call allows you to trace the nitty-gritty details when moving from outer recursive call to inner.

- Step Out of a recursive call allows you to follow along with the action when backtracking from an inner recursive call to the outer one.

Using Step In, Step Over, and Step Out, it’s possible to watch recursion work at different levels of detail. Step In lets you see what’s going on at each point in time. Step Over lets you see what a recursive function does in its entirety. Step Out lets you run the current stack frame to completion to see how the code behaves as a whole.

2) Test and debug the buggy subset sum

Your next task is to use the debugger to do what it’s designed for – to debug a program!

Forming all possible subsets of a collection is one of the classic recursive patterns. Each node in the decision tree takes one element under consideration and branches into two recursive calls, one that includes the element and another that excludes it. The decision tree grows to a depth of N where N is the total number of elements in the collection. You have seen this in/out pattern in solving such problems as subset sum, choose k of n, partition, isMeasurable, knapsack, and more.

The warmup includes a function that counts those subsets whose members sum to zero. Consider forming the subsets from the collection {3, 1, -3}. The list of all possible subsets is { {3, 1, -3}, {3, 1}, {3, -3}, {1, -3}, {3}, {1}, {-3}, {} } and there are 2 subsets that sum to zero: {3, -3} and {}. Look over the implementation for countZeroSumSubsets to be sure your understand how it works before you begin debugging.

In addition to the correct implementation, there is a buggyCount version that contains a small but significant error. It’s not that far from working correctly – in fact, it comes down a difference of one character – but what difference a single character can make! Your task is to use the debugger to figure out the following:

- What is the one-character mistake in the program?

- With the one-character mistake in the program, what does the program actually do? And why is that not what we want it to do?

Add student test cases to try various inputs and observe the difference between what’s produced and what’s supposed to be produced. It can be difficult to tease out the impact of the bug when you are tracing through a deep sequence of recursive calls. Try a variety of simple inputs to find the smallest possible input for which you can observe an error and use that as your test case. Specifically, you’re aiming to find an input where

- the output produced is wrong, and

- no shorter input produces the wrong answer

Using your minimized test case, trace the operation of

countZeroSumSubsets to observe the correct behavior. Diagram the decision

tree that is being traversed and match the tree to what see in the

debugger as you step in/out/over. Select different stack frames in the

call stack to see the state being maintained in each of the outer

frames.

After completing a thorough walkthrough of the correct version, now trace the buggy version on the same input case. Watch carefully to see where in the process the bug manifests itself and how things veer off-course.

Once you have, answer the following questions by editing the short_answers.txt.

- Q4: What is the smallest possible input that triggers the bug?

- Q5: What is the one-character error in the program?

- Q6: Explain why that one-character bug causes the function to return the exact output you see when you feed in the input you provided in Q4. You should be able to specifically account for where things go wrong and how the place where the error occurs causes the result to change from “completely correct” to “terribly wrong.”

We’ve asked you to answer these questions because this sort of bug-hunting is useful for understanding recursive functions and what makes them break.

When trying to debug a recursive function, look for the simplest case where the recursion gives the wrong answer. Having a small test case makes it easy to reproduce the error and to trace through what’s happening in the debugger.

Happy bug hunting!