A maze is a twisty and convoluted arrangement of corridors that challenge the solver to find a path from the entry to the exit. This assignment task is about using ADTs to represent, process, and solve mazes.

An introduction to mazes

Labyrinths and mazes have fascinated humans since ancient times (remember Theseus and the Minotaur?), but mazes can be more than just recreation. The mathematician Leonhard Euler was one of the first to analyze mazes mathematically, and in doing so, he founded the branch of mathematics known as topology. Many algorithms that operate on mazes are closely related to graph theory and have applications to diverse tasks such as designing circuit boards, routing network traffic, motion planning, and social networking.

Your goal for this part of the assignment to implement a neat algorithm to solve a maze, while gaining practice with ADTs.

Before you jump into code, please carefully read this background information on how we will represent mazes, which ADTs to use, and the format of the provided maze data files.

A Grid represents a maze

A maze can be modeled as a two-dimensional array where each element is either a wall or a corridor.

- The

Gridfrom the Stanford library is an ideal data structure for this. A maze is represented as aGrid<bool>. - Each grid element is one "cell" of the maze. The boolean value for each element indicates whether that cell is a corridor.

- The element

grid[row][col]istruewhen there is a open corridor at location (row, col) andfalseif it is a wall.

A maze is read from a text file. Each line of the file corresponds to one row of the maze. Within a row, the character @ is used for walls, and - is used for corridors. Here is a sample 5x7 maze file (5 rows by 7 columns):

-------

-@@@@@-

-----@-

-@@@-@-

-@---@-

Our starter code provides the readMazeFile function that reads the above text file into a Grid<bool>. In the project "Other files/res" folder are a number of provided maze files.

A GridLocation is a row/col pair

The GridLocation struct is a companion type used to present a row/col location in a Grid. A GridLocation has two fields, row and col, that are packaged together into one aggregate type. The sample code below demonstrates using a GridLocation variable and assigning and accessing its row and col fields.

// Declare a new GridLocation

GridLocation chosen; // default initialized to 0,0

chosen.row = 3; // assign row of chosen

chosen.col = 4; // assign col of chosen

// Initialize row,col of exit as part of its declaration

GridLocation exit = { maze.numRows()-1, maze.numCols()-1 }; // last row, last col

// You can use a GridLocation to index into a Grid (maze is a Grid)

// This checks if maze[chosen] is an open corridor

if (maze[chosen]) // chosen was set to {3, 4} so this accesses maze[3][4]

...

// You can directly compare two GridLocations

if (chosen == exit)

...

// You can also access a GridLocation's row,col separately

if (chosen.row == 0 && chosen.col == 0)

...

A Stack of GridLocations is a path

A path through the maze is a sequence of connecting GridLocations. The sequence is stored into a Stack<GridLocation>. To extend a path, push an additional GridLocation onto the stack. Peeking at the top of the stack accesses the end location of the path. A valid maze solution path must start at the maze entrance (bottom of stack), travel through connecting GridLocations, and end at the maze exit (top of stack).

Along with the maze text files in the "Other files/res" folder, there are .soln text files that contain maze solutions. For example, this is the solution file corresponding to the 5x7 maze shown previously. (The elements in a stack are written in order from bottom to top)

{r0c0, r0c1, r0c2, r0c3, r0c4, r0c5, r0c6, r1c6, r2c6, r3c6, r4c6}

Our starter code provides the readSolutionFile function that reads a solution text file into a Stack<GridLocation>. Not every maze will have a corresponding .soln file, and part of your job is to write code to generate solutions!

ADT resources

- Documentation for Stanford collections: Grid, GridLocation, Stack, Queue

- Section 6.1 of the textbook introduces

structtypes - In the lower-left corner of your Qt Creator window, there is a magnifying glass by a search field. If you type the name of a header file such as

grid.horgridlocation.h, Qt will display the corresponding header file.

Notes on Stanford collection types

- The assignment operator for our ADTs makes a deep copy. Assigning from one Stack, Vector, Set, … to another creates a copy of the ADT and a copy of all its elements.

- Take care to properly specialize a template type and ensure all types match. Using

Vectorwithout specifying the element type just won't fly, and aVector<int>is not the same thing as aVector<string>. The error messages you receive when you have mismatches can be cryptic and hard to interpret. Bring your template woes to LaIR or the Ed forum, and we can help untangle them with you.

On to the code!

Your work is structured in three tasks: two helper functions that process grids and paths and a final pièce de résistance to solve the maze. You will also be writing comprehensive test cases for your functions. All of the functions and tests for mazes are to be implemented in the file maze.cpp.

1) Write generateValidMoves()

Your first task is to implement the helper function to generate the neighbors for a given location:

Set<GridLocation> generateValidMoves(Grid<bool>& maze, GridLocation cur)

Given a maze represented as a Grid of bool and a current cell represented by the GridLocation cur, this function returns all valid moves from cur as a Set. Valid moves are those GridLocations that are:

- Exactly one "step" away from

curin one of the four cardinal directions (N, S, E, W) - Within bounds for the

Grid - An open corridor, not a wall

There are a few provided tests for generateValidMoves, but these tests are not fully comprehensive. Write at least 3 additional tests to make sure your helper function works correctly. Remember to label your tests as STUDENT_TEST.

2) Write validatePath()

Next you'll write a function to confirm that a path is a valid maze solution:

void validatePath(Grid<bool>& maze, Stack<GridLocation> path)

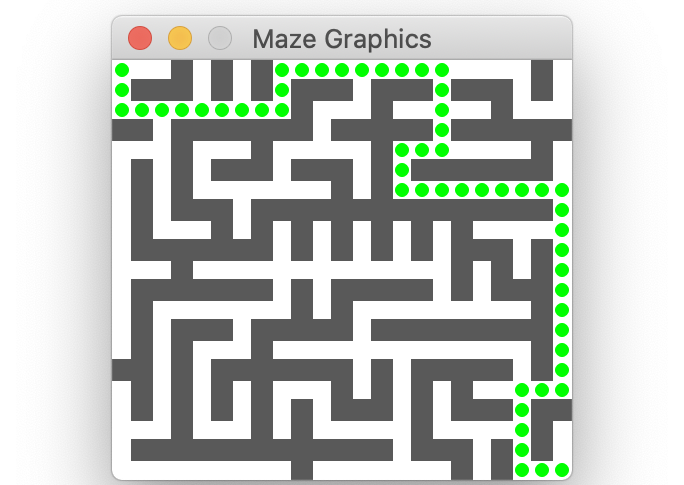

The image above displays a valid solution; each green dot marks a GridLocation along the path. A path is a valid solution to a maze if it meets the following criteria:

- The path must start at the entry (upper left corner) of the maze

- The path must end at the exit (lower right corner) of the maze

- Each location in the path is a valid move from the previous location in the path

- Hint: rather than re-implement the same logic you already did for

generateValidMoves, simply call that function and check whether a move is contained in the set of valid moves.

- Hint: rather than re-implement the same logic you already did for

- The path must not contain a loop, i.e. the same location cannot appear more than once in the path

- Hint: a

Set<GridLocation>is a good data structure for tracking seen locations and avoiding a repeat.

- Hint: a

If validatePath detects that a path violates one of the above constraints, use the error function from error.h to report what is wrong. When you call error, it stops the program and reports the message you passed as an argument:

error("Here is my message about what has gone wrong");

If all of the criteria for a valid solution are met, then validatePath completes normally.

Q5. In lecture, Cynthia noted the convention is to pass large data structures by reference for reasons of efficiency. Why then do you think validatePath passes path by value instead of by reference?

This function has quite a few different things to confirm and will need rigorous tests to verify all of its functionality. We've provided some initial tests to get you started, but you will need to write tests of your own. Write at least 3 student test cases for validatePath.

After writing validatePath, not only will you be familiar with using the ADTs to represent mazes, but you will also have a function that makes testing the next milestone much easier. Having thoroughly tested your validatePath on a variety of invalid paths means you can be confident that it is the oracle of truth when it comes to confirming a solution. Your future self will thank you!

Note the use of the new test types EXPECT_ERROR and EXPECT_NO_ERROR in our provided tests. An EXPECT_ERROR test case evaluates an expression, expecting that the operation will raise an error. While the test is executing, SimpleTest framework will catch the error, record that it happened, and resume. Because the error was expected, the test case is marked as Correct. If an error was expected but didn't materialize, the test case fails. This is the opposite of an EXPECT_NO_ERROR test case, which is expecting the code to run without errors and treats a raised error as a test failure. More information on the different test macros and how they all work can be found in the CS106B Testing Guide.

Q6. After you have written your tests, describe your testing strategy to determine that your validatePath works as intended.

3) Write solveMaze()

Now you're ready to tackle the final task, writing the function to find a solution path for a maze:

Stack<GridLocation> solveMaze(Grid<bool>& maze)

Solving a maze can be seen as a specific instance of a shortest path problem, where the challenge is to find the shortest route from the entrance to the exit. Shortest path problems come up in a variety of situations such as packet routing on the internet, robot motion planning, analyzing gene mutations, spell correction, and more.

Breadth-first search (BFS) is a classic and elegant algorithm for finding a shortest path. A breadth-first search reaches outward from the entry location in a radial fashion until it finds the exit. The first paths examined take one hop from the entry. If any of these reach the exit location, you’re done. If not, the search expands to those paths that are two hops long. At each subsequent step, the search expands radially, examining all paths of length three, then of length four, etc., stopping at the first path that reaches the exit.

Breadth-first search is typically implemented using a queue. The queue stores partial paths that represent possibilities to explore. The first paths enqueued are all length one, followed by enqueuing the length two paths, and so on. Because of the queue's FIFO behavior, all shorter paths are dequeued and processed before the longer paths make their way to the front of queue. This means the paths are tried in order of increasing length.

At each step, the algorithm considers the current path at the front of the queue. If the current path ends at the exit, it must be a completed solution path. If not, the algorithm takes the current path, extends it to reach locations that are one hop further away in the maze, and enqueues those extended paths to be examined in later rounds.

Here are the steps followed by a breadth-first search:

- Create an empty queue of paths. Each path is a

Stack<GridLocation>and the queue of paths is of typeQueue<Stack<GridLocation>>.- A nested ADT type like this looks a little scary at first, but it is just the right tool for this job!

- Create a length-one path containing just the entry location. Enqueue that path.

- In our mazes, the entry is always the location in the upper-left corner, and the exit is the lower-right.

- While there are still more paths to explore:

- Dequeue the current path from queue.

- If the current path path ends at exit:

- You're done. The current path is the solution!

- Otherwise:

- Determine the viable neighbors from the end location of the current path. A viable neighbor is a valid move that has not yet been visited during the search

- For each viable neighbor, make copy of current path, extend by adding neighbor and enqueue it.

A couple of notes to keep in mind as you're implementing BFS:

- You may make the following assumptions:

- The maze is well-formed, rectangular, contains at least two rows and two columns, and the grid locations at upper-left (enter) and lower-right (exit) are both open corridors.

- The maze has a solution.

- The search should not revisit previously visited locations or create a path with a cycle. For example, if the current path leads from location

r0c0tor1c0, you should not extend the path by moving back to locationr0c0. - You should not call

validatePathwithin yoursolveMazefunction, but you can call it in your test cases to confirm the validity of paths found bysolveMaze. - A strategy that will help with visualizing and debugging

solveMazeis to add calls to our provided graphic animation functions, explained below.

We have provided some existing tests that put your solveMaze functions to the test. Add 2 or more student tests that further verify the correct functionality of the solveMaze function. Note there are a number of additional maze files in the res folder that can be useful. You can also create your own files.

Add graphics functions to draw the maze

The Stanford C++ library includes extensive functionality for drawing and user interaction, but we generally won't ask you to dig into those features. Instead, we will supply any needed graphics routines pre-written in a simple, easy-to-use form. For this program, the provided mazegraphics.cpp module has functions to display a maze and highlight a path through the maze. Read the mazegraphics.h header file in the starter project for details of these functions:

MazeGraphics::drawGrid(Grid<bool>& grid)MazeGraphics::highlightPath(Stack<GridLocation> path, string color, int mSecsToPause = 0)

To call these functions, you must refer to them using their full name (including the weird looking MazeGraphics:: prefix). We will talk more about what this notation means a little later in the quarter!

Call MazeGraphics::drawGrid once at the start of solveMaze to draw the base maze and then repeatedly call MazeGraphics::highlightPath to mark the cells along the path currently being explored. You can use the optional pause argument to slow down the animation to help you understand the algorithm and debug its operation. This gives you time to watch the animation and see how the path is updated and follow along with the algorithm as it searches for a solution.

Now sit back and watch the show as your clever algorithm finds the path to escape any maze you throw at it! 👏 Congratulations! 👏

References

There are many interesting facets to mazes and much fascinating mathematics underlying them. Mazes will come up again several times this quarter. Chapter 9 of the textbook uses a recursive depth-first search as path-finding algorithm. At the end of the quarter when we talk about graphs, we'll explore the equivalence between mazes and graphs and note how many of the interesting results in mazes are actually based on work done in terms of graph theory.

- Walter Pullen, Maze Classification. http://www.astrolog.org/labyrnth/algrithm.htm Website with lots of great info on mazes and maze algorithms

- Jamis Buck. Maze Algorithms. https://www.jamisbuck.org/mazes/ Fun animations of maze algorithms. He also wrote the excellent book about Mazes for Programmers: Code Your Own Twisty Little Passages.

Extensions

If you have completed the assignment and want to explore further, here are some ideas for extensions.

- Instead of reading pre-written mazes from a file, you could instead generate a new random maze on demand. There is an amazing (I could not resist…) variety of algorithms for maze construction, ranging from the simple to the sublime. Here are a few names to get you started: backtracking, depth-first, growing tree, sidewinder, along with algorithms named for their inventor: Aldous-Broder, Eller, Prim, Kruskal, Wilson, and many others.

- Try out other maze solving algorithms. How does BFS stack up against the options in terms of solving power or runtime efficiency? Take a look at random mouse, wall following, depth-first search (either manually using a Stack or using recursion once you get the hang of it), Bellman-Ford, or others.

- There are many other neat maze-based games out there that make fun extensions. You might gather ideas from Robert Abbott's http://www.logicmazes.com or design a maze game board after inspiration from Chris Smith on mazes.