1) Examine recursive stack frames (factorial)

The factorial n! is defined as the product n * (n-1) * (n-2) * ... * 3 * 2 * 1. The recursive approach to computing factorials uses the insight that:

0!is defined to be1n!can be computed asn * (n-1)!

To express this in code, we write a base case to return 1 for zero and use a recursive case to compute the result for n building on the result from n-1.

Open the assignment starter project in Qt. Find the file warmup.cpp and review the provided code for the factorial function. It follows the recursive structure described above. We will use this function as practice for examining recursive stack frames.

Add a breakpoint on the line return 1 within the base case of factorial. Run the program in Debug mode and when prompted, select the test group warmup.cpp. When your program stops at the breakpoint, look to the lower middle/left of your debugger and find Call Stack pane (see screenshot below):

This pane displays the current call stack, the sequence of active functions leading up to the point where the breakpoint was reached. Each entry in the call stack corresponds to a function that has been called and not yet finished executing.

The innermost level (Level 1) is the currently executing function. It was called from the function at Level 2, who was called from Level 3 and so on.

The small yellow arrow next to Level 1 indicates that this function is currently selected. Elsewhere in debugger window, the Editor pane (upper left of debug window) shows the source lines for the selected function and the Variables pane (upper right of debug window) displays the value of the variables of the selected function.

In the call stack pane, click the function at Level 2 and the yellow arrow

moves to indicate this function is now selected. The Editor pane and the Variables pane update to show the source code and data for this function. Click to select Level 3, and then Level 4. As you move through the levels, look at the Variables pane and note that each recursive call has its own independent copy of n that is distinct from the other n variables that belong to the other function calls.

Each active function on the call stack has a place designated in the computer's memory to store its own parameters and variables. The function's storage is called its "stack frame."

When stepping through a deep recursive sequence, it is easy to become confused with so many similar stack frames. Look for that yellow arrow in the call stack pane to confirm which level of the recursion is currently selected.

Q1. Looking at a call stack listing in a debugger, what is the indication that the program being debugged uses recursion?

2) Recognize stack overflow (factorial)

The one provided test tries factorial(7) and confirms the result is correct. What other inputs should be tested? In mathland, factorial is defined only for non-negative numbers, hmmm…. so what should happen in C++ land if you try to evaluate factorial(-3)? Perhaps an error? Trace the code and make your own prediction of the outcome.

Add a STUDENT_TEST that expects an error from factorial(-3). Run the program normally, not in Debug mode, and observe. Boom! When attempting to run that test, the program unceremoniously exits, right in the middle of execution with no explanation of what went wrong.

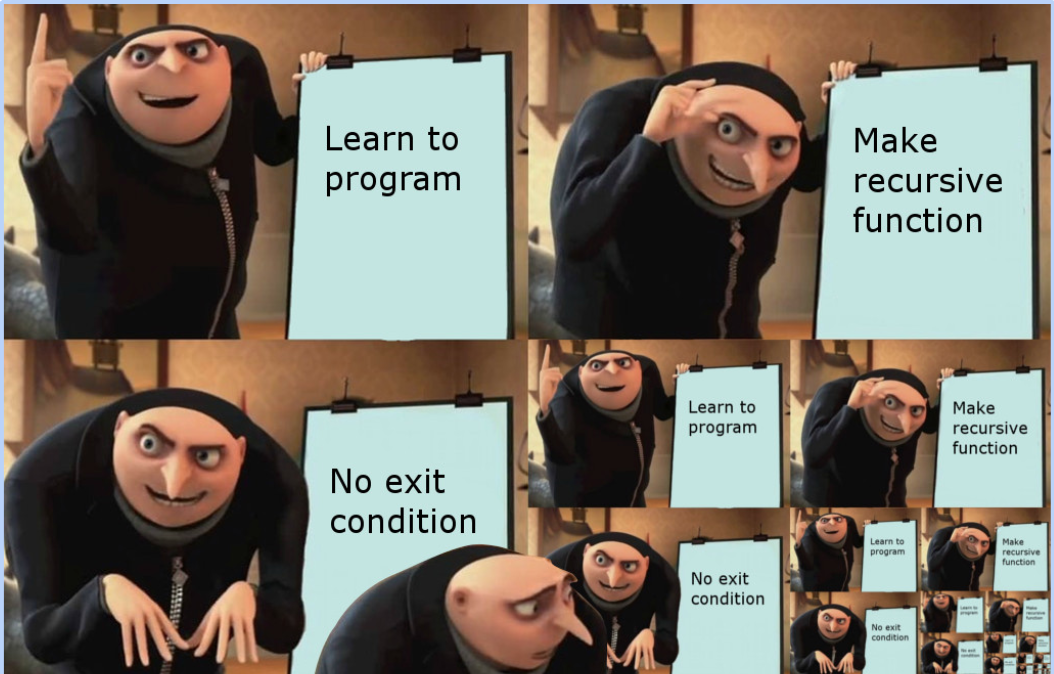

In the past when our program raised an error, SimpleTest caught the error and reported it with a helpful message. But this particular error, stack overflow, is too slippery to be tamed. A stack overflow occurs when a function recursively calls itself without end. Each call to the function requires storage space for its stack frame and the unceasing growth of stack frames eventually exhausts the total amount of memory set aside for the call stack.

For ordinary errors, our libraries can detect and report the problem and perhaps even gracefully recover. But the catastrophic

nature of stack overflow in C++ causes a hard, unavoidable program crash. The Application Output tab in the Qt window gives only a terse mention that the program "unexpectedly quit" or "ended forcefully" and nothing more.

This is an opportunity for the debugger to save the day! By running under the debugger, you gain the ability to stop at the time of the crash and use the debugger to inspect the program state at the critical moment.

Delete any breakpoints and re-run the program in Debug mode. Your student test causes a stack overflow just as before, but the program is now running under the watchful eye of the debugger. The debugger sees the crash coming, prevents the program from exiting, suspends the current state and shows it in the debugger window. Using the debugger, you can find out what code was executing at the time of the crash, examine the values of your variables and so on.

A key piece of information available in the debugger is the call stack, which shows where the program was executing at the time of the crash and the sequence of steps that led up to this point. When the call stack pane is filled with level after level of the same recursive function calling itself non-stop, this is the evidence that loudly shouts, "Uh oh, stack overflow".

This will probably not be last time you need to diagnose a stack overflow, so learn how to recognize it!

Click to select different levels on the call stack (say, Level 1, then Level 2, and few beyond) and observe how the value of the parameter n changes for each level. Scroll down to the bottom of the call stack, clicking "More…" a few times to fully expand and show all the frames. Near the bottom, you will find the initial call to factorial(-3), the one was called from the test case. This is the call that started it all.

The level at the top of the list (numbered Level 0 or Level 1) is the innermost. At the bottom of the list is the outermost level; it has the largest level number. Scroll down to the outermost level and find its level number now. You may have to drag the column divider to enlarge the column width to fit all the digits and hit the "More" button at the bottom to show all the frames.

Q2. Subtract the innermost level number from the outermost to get the maximum count of stack frames that fit in the capacity of the call stack. How many stack frames fit in your system's call stack?

Note: If a program has hit stack overflow, the situation is rather fragile and Qt may run into trouble when you try to examine the call stack. Here are a few oddities to watch out for:

- The variables of the innermost frame may have unreliable values. The innermost frame was the final straw that broke the camel's back. The crash occurred while adding this frame, interrupting the process of initializing the parameters and variables. In such a case, instead look at the frame one level away which should have reliable values.

- Scrolling down to the outermost frame may hit an abrupt end before you get to the true bottom of the call stack. This can be a matter of what is displayed/not (e.g. Qt Creator limiting the number of frames to display, eliding the others) but in dicier situations, Qt can itself crash when you ask it to show more frames. If Qt isn't being cooperative, you can estimate the count of frames from top to bottom by examining the value of

nin the innermost frames and comparing tonin the outermost recursive call (which you know is the initial callfactorial(-3)).

In the warmup of last week's assignment, you used the debugger to diagnose the symptom of an infinite loop. Above you have just learned to diagnose infinite recursion. Although the root cause to both errors is somewhat similar (a repeating process that fails to terminate), they present with different symptoms.

Q3. Describe how the symptoms of infinite recursion differ from the symptoms of an infinite loop.

Edit the code of factorial to fix the problem. When given a negative argument, factorial should call error. Re-run to confirm that your fix works. There should be no infinite recursion, no stack overflow, your student test case should pass and provide a helpful error message. Much better!

3) Testing a recursive function (myPower)

The warmup.cpp file contains a recursive function to compute raising a base number to a power. The comments for the function warn that the implementation is buggy. Your first task is to write test cases to expose its bugs.

The C++ library contains a pow function that is known to be correct[^1], which makes it perfect to use for cross-comparison with the buggy myPower. A simple approach is to call the two functions passing the same arguments and compare the results for equality:

PROVIDED_TEST("myPower(), compare to library pow(), fixed inputs") {

EXPECT_EQUAL(myPower(7, 0), pow(7, 0));

EXPECT_EQUAL(myPower(10, 2), pow(10, 2));

EXPECT_EQUAL(myPower(5, -1), pow(5, -1));

EXPECT_EQUAL(myPower(-3, 3), pow(-3, 3));

}

The above provided test is a simple "spot check" on a few fixed inputs. It's a good start, but not particular thorough or comprehensive.

Much better than enumerating individual cases is using code in the test case to mechanically generate a range of inputs, such as shown in the loop below. Neat! With this approach, you can easily broaden your coverage with a simple change to the loop range.

PROVIDED_TEST("myPower(), generated inputs") {

for (int base = 1; base < 25; base++) {

for (int exp = 1; exp < 10; exp++) {

EXPECT_EQUAL(myPower(base, exp), pow(base, exp));

}

}

}

Run the above tests on myPower and the function passes with flying colors. Yet the comments say the function is buggy, so what's missing from our testing coverage?

You note that the fixed input test does include a few negative values, however the loop test iterates over strictly positive ranges. Copy the provided loop test and make your own STUDENT_TEST that expands the ranges to cover both negative and positive values for base and exp.

Running your new test should show that a negative exp is no problem, but there are test failures for some negative values of the base number.

The test failure message reports the mismatched result, but you may also need to see the values of base and exp. If you add a cout statement to print base and exp just before EXPECT_EQUAL this will give a running commentary about the inputs being tested. Look for the last values printed before the test failure; this is what triggered the failure. Experiment with your test case to narrow in on the pattern of which specific inputs fail.

Q4. What is the pattern to which values of base number and exponent result in a test failure?

Write a student test with a few fixed inputs that specifically reproduce the failure. Don't worry about fixing the bug just yet, we'll do that in the next section!

4) Debugging a recursive function (myPower)

Unlike the simpler recursive functions we've seen that have just one base case and one recursive case, the provided code for myPower has five cases in total, two base cases and three recursive cases. This seems like a lot; are they all truly needed? The best design avoids unnecessary cases that overlap or are redundant. Not only is piling on the extra cases wasteful and stylistically poor, it can also introduce functionality bugs.

Before continuing on with more testing, step back and try to reason about the situation. Consider the observations you have made during testing. Answer the following question before going on (please note that we're not looking for a "correct" answer here —we want to hear your honest impression before you dig in deeper):

Q5. Of the existing five cases, are there any that seem redundant and can be removed from the function? Which do you think are absolutely necessary? Are there any cases that you're unsure about?

Now, let's settle that question once and for all with further testing to confirm what's up with each case.

Testing has shown a problem with a negative base number and the code has a specific case for base < 0. Could it be the source of the trouble? Trace the code and predict what would happen if this code were removed entirely. Comment it out and rebuild and run the program to see if your prediction was correct.

You were correct that it was unnecessary to make a special case out of negative base numbers, and furthermore the code within that special case had a bug, making it especially unwelcome. Removing it not only cleans up the design, it also resolves the test failure for negative base number. That's what I call a win-win!

You are down to four cases and wonder if you can streamline further. The two recursive cases both seem clearly necessary but why do we have two separate base cases? The recursive steps advance toward the exp == 0 case so that code is a keeper, but the special code to handle a base number of zero seems a bit suspect.

Zero raised to any exponent should be zero, right? Predict what will happen if you remove the special handling for base == 0. Edit myPower to remove that code and re-run your tests.

Voila! All still works correctly, which tells you that the code was redundant and unnecessary. Although its presence wasn't specifically causing a problem, the extraneous code is cluttering and adds to your cognitive burden. More cases means more code to read, more cases to test, and more code to debug. By taking care to enumerate exactly and only the essential code paths, you not only simplify your code, but also streamline your process for testing and debugging that code.

Save the modified file with your additional test cases and fixed code. Be sure to include your edited warmup.cpp as part of your assignment submission.

[^1]: Late-breaking news (10/8/2021): The version of pow in the library used on Windows turns out to not be a reliable reference. I just confirmed it takes a computational shortcut in calculating the result which can sometimes cause the last decimal place to be minutely different than the result computed by repeated multiplication/division (e.g. how myPower function calculates it). Comparing the result of myPower to pow will match for most inputs, but also can happen that result is very very close, but not perfectly equal, and give erroneous test case failure. If you encounter these tiny discrepancies, just ignore them (and take CS107 to learn more about why precision in floating point comparison is hard for binary computers!)