Use these debugging warmup exercises to practice with the tools and skills that will arm you to successfully manage the tricky aspects of linked lists. A good understanding of memory and pointers is essential. These are difficult concepts in C++, and you can never get too much practice.

Using SimpleTest to find memory leaks

A memory leak is created when a program allocates memory using new but does not call delete to deallocate the memory when finished with it.

Unlike a memory error, which can cause a program to crash or behave erratically, a memory leak has fairly benign consequences. The side effect of a memory leak is that the leaked memory is not available for recycling. If a program had many leaks and each was a large amount of memory, it could eventually exhaust all of the system memory and be unable to proceed further, but this happens only in extreme cases.

If you use a tool such as Activity Monitor or top to watch a long-running application, you'll likely see its memory usage creep upwards over time, in some part due to unresolved memory leaks. Even professionals slip up sometimes! Memory leaks are endemic to any program written in a language where the programmer is responsible for explicit deallocation (as opposed to a language such as Python, which has automatic garbage collection. Oh those halcyon days of CS106A…)

Tracking down memory leaks by hand is painstaking and difficult; most developers rely on industrial-strength memory debugging tools such as Valgrind or memcheck. Our SimpleTest framework has a basic facility to identify leaks by counting the new and delete calls and reporting when the two counts don't match up.

Enable leak-checking for the ListNode type by adding the SimpleTest macro TRACK_ALLOCATIONS_OF to its type declaration, like this:

struct ListNode {

int data;

ListNode *next

TRACK_ALLOCATIONS_OF(ListNode);

};

Once ListNode is configured in this way, its allocations are tracked by SimpleTest. Each test case will count the new and delete calls for ListNodes, and any count mismatch is reported in the test result.

Observing memory errors and memory leaks

The first three provided test cases in warmup.cpp demonstrate mismatched allocation counts on ListNodes. The title of each test states the expected count of new and delete operator. For each case, trace the code to confirm the counts and identify whether the mismatch will result in a memory error (dangerous) or a memory leak (more benign). Run the cases and observe the test results as reported by SimpleTest to confirm your understanding is correct.

Answer the following questions in short_answer.txt:

Q1. What does the yellow background for a test case indicate in the SimpleTest result window?

Q2. What is the observed consequence of a test that uses delete on a memory address that has already been deallocated?

When working with test cases that are designed with intentional mistakes, it is best to comment them out after you have finished examining them. In this way you can proceed onto other tests without that corruption/interference of those planted errors. Comment out the allocation count tests now before moving on.

Accessing deallocated memory

The warmup.cpp file has a provided function badDeallocate that attempts to deallocate the nodes of a linked list, but has a nasty bug lurking within.

void badDeallocate(ListNode* list) {

while (list != nullptr) {

delete list;

list = list->next; // BAD: accesses next field from deallocated memory

}

}

The statement delete list recycles memory for the ListNode pointed to by list. The very next statement accesses that deallocated memory to read the list->next field. This is clearly a wrong thing to do, but even this blatant mistake may manage to pass unnoticed and unpunished. Why is that? It may help to consider exactly what is the effect of the delete operation. A call to delete tells the system that we are done using the memory at this address. That location in memory is marked as available for recycling, but the system does not necessarily wipe the contents or make the memory inaccessible. Thus a mistaken access to memory after it has been deleted can sometimes "succeed", even though such code is in the wrong.

Continuing the hotel room analogy from lecture, if you were to rush back to the hotel room you just checked out of to grab your forgotten toothbrush, well… you just might get away with it. But what if you go into your former room after if housekeeping has come and swept it clean, or even worse, the room has been re-assigned to a new customer who now occupies it? Although you might sometimes get away with the error, your code is not correct; merely "lucky." The next time you run that same code, your transgression might result in a crash. The unpredictable, intermittent symptoms that can result from a memory error make these bugs particularly difficult to track down.

Observing a memory error

The warmup.cpp file has two test cases for badDeallocate. Uncomment those test cases and trace through the code.

The first test case makes one call to the buggy function badDeallocate on a small list. The loop within badDeallocate will make three accesses to memory locations that were deleted. Despite these memory errors, this test case will likely "pass" on many systems.

The second test case makes many calls to badDeallocate on much longer lists. By repeating the same mistake so many more times, it becomes more likely that one will trigger a more visible consequence. Run the test as-is a few times and note if you see any consequences of the bug. Running the exact code unchanged can sometimes produce different results than the previous run. If you see no consequences, try doubling the number of trials or increasing the lengths of the list. On your system, you may find it easy to trigger the bug, or you might find it completely impossible. These experiments will demonstrate that getting definitive evidence of a memory error can be elusive indeed! The next time you are puzzling over how it makes no sense for code to fail only one isolated test when all others pass all test cases, remember these results and recall how slippery memory errors can be.

Answer the following question in short_answer.txt:

Q3. On your system, what is the observed consequence of badDeallocate? Under what circumstances (if any) did the buggy code trigger an error or crash?

After you finish exploring badDeallocate, comment out those test cases so that they don't interfere with further tests.

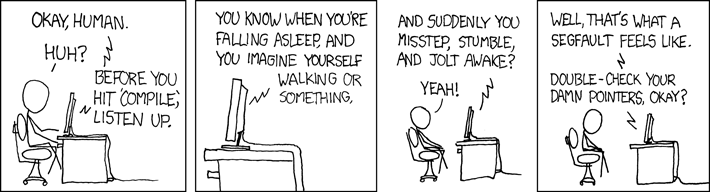

Debugging a segmentation fault

A common experience when debugging code that uses pointers is the dreaded Segmentation Fault. This is a fatal error or crash that will stop your program immediately. A segmentation fault indicates that the program attempted to access an invalid address, i.e. tried to read from or write to a memory location that cannot be accessed. A segmentation fault is a symptom of the bug, but it is not the bug itself. The bug is that your program uses an invalid address, and that bug causes a crash. You must work backwards from the symptom to figure how and why you ended up with that invalid address so you can correct the bug.

One frustrating thing about a segmentation fault is that the way it presents itself may vary because the memory error confuses the system/debugger. In the best of situations, the program halts and provides a clear and descriptive error message, perhaps via an alert dialog or a text message in the console. In other situations, a program might suddenly stop but be silent on the error message. In another, the program may exit, and its windows disappear, leaving no trace of what happened. In yet another, the program might lock up, as though stuck in an infinite loop.

To complicate matters even further, running the program under the debugger may produce a different result than running outside the debugger. Even running the same program twice in a row in the exact same context can produce different results. Working with memory errors can cause you to doubt your own eyes and sanity. We want you to be aware that any and all of the above may be part of the landscape when it comes to memory woes.

One possible root cause for an address to be invalid is when a pointer was not properly initialized. We will have you debug such an example so you can observe a segmentation fault in action.

Uncomment the "Segmentation fault" test case at the end of warmup.cpp and rebuild. Set a breakpoint in this test case and run the program in Debug mode.

The test code allocates memory for a new ListNode and stores that address in the pointer variable p. p now holds the address of the memory where the ListNode is stored. In the Variables panel, the value of p is shown as a longish hexadecimal number prefixed with @0x. Look for it now.

Click on the triangle of p to expand it and see the two fields in the ListNode: data and next. Neither of these fields were initialized so their contents are unpredictable/garbage.

Let's observe the consequence of using a garbage integer value.

Step through the statement that increments p->data and watch the value of

data update. What is the value before and after? Adding to a garbage value doesn't make much sense, but it doesn't appear to cause the program to halt or fail. And on some systems, the uninitialized value may not even look like "garbage"!

Not all garbage is created equal. The pointer variable p->next is also not initialized. Accessing a garbage address can cause a runtime error. An uninitialized/garbage address could happen to be a valid location, but more often that not, it won't be. It is somewhat analogous to picking up your phone and dialing digits at random – does the call go through and you talk to a stranger, or do you get an error because the number is out of service? Either way, the random dialing was a bad idea, but the observed consequence can differ depending on your "luck." This variation adds a layer of challenge to debugging memory errors.

Use the Variables pane to see the garbage address stored in the p->next field. Does it look like a valid address (compare its value to the valid address stored in p)?

Step though the statement that attempts to dereference p->next. This dereference will likely cause a segmentation fault. The debugger should halt the program. It may produce an alert or error message, or it might stay silent. After a segmentation fault, the debugger will refuse to step further. The yellow arrow in the editor pane will indicate the offending line that caused

the crash, and you can read the values in the Variables pane to see the invalid address. These are the clues that help you diagnose the symptom.

Observing a segmentation fault

A segmentation fault might present itself differently depending on the context:

- If the program is executing in Debug mode, the debugger will generally stop the program at the point of the segmentation fault. There may or may not be an alert or error message. The yellow arrow will point to the offending line, and the call stack will show the function calls leading up to the crash. This display looks similar to stopping at a breakpoint, so it may not be immediately apparent that this situation is due to a crash. If you try to continue/step from a crash, though, the debugger will refuse. Try this now with the buggy program – remove all breakpoints and run under the debugger to see how the crash is reported/presented.

- In some situations, the program may go unresponsive when it tries to access an invalid memory address. If this happens, use "Interrupt" from the "Debug" menu to stop the program and return control to the debugger so you can examine the current program state.

- If the program is executing not in Debug mode, it will crash and exit on a segmentation fault. An error message is written in red text to the the console window, but the window closes too quickly to read. In Qt Creator, you can click on the Application Output tab in the bottom pane to see the error message. Try this now with the buggy program. This error message is a summary of the situation at the point of the crash, but it's a little thin on details. Your follow-up will typically be to run the same program again in Debug mode so you can get more complete information to help diagnose the symptom.

Answer the following question in short_answer.txt:

Q4. How is a segmentation fault presented on your system?

Recognizing a segmentation fault can itself be tricky, but this is only the first step. From there, you must work backwards from the symptom to figure how and why you ended up with that invalid address so you can correct the bug. There is no simple one-size-fits-all fix for segmentation faults; resolving one is an adventure that will draw upon your finest debugging skills. Drawing pictures of the memory and its connections is often a good start. Tracing the execution by using the debugger to step through and observe the state may help confirm whether or not your code is doing what you intend.