You have been trapped in a labyrinth, and your only hope to escape is to cast the magic spell that will free you from its walls. To do so, you will need to explore the labyrinth to find three magical items:

- The Spellbook (📕), which contains the spell you need to cast to escape.

- The Potion (⚗), containing the arcane compounds that power the spell.

- The Wand (⚚), which concentrates your focus to make the spell work.

Once you have all three items, you can cast the spell to escape to safety.

This is, of course, no ordinary maze. It’s a pointer maze. The maze consists of a collection of objects of type MazeCell, where MazeCell is defined here:

struct MazeCell {

Item whatsHere; // Item present, if any.

MazeCell* north; // The cell north of us, or nullptr if we can't go north.

MazeCell* south;

MazeCell* east;

MazeCell* west;

};

Here, Item is this enumerated type:

enum class Item {

NOTHING, SPELLBOOK, POTION, WAND

};

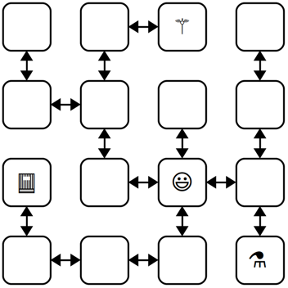

For example, here is a 4 × 4 labyrinth.

We’ve marked your starting position with a smiley face and the positions of of the three items with similarly cute emojis. The MazeCell you begin at would have its north, south, east, and west pointers pointing at the MazeCell objects located one step in each of those directions from you. On the other hand, the MazeCell containing the book would have its north, east, and west pointers set to nullptr, and only its south pointer would point somewhere (specifically, to the cell in the bottom-left corner).

Each MazeCell has a variable named whatsHere that indicates what item, if any, is at that position. Empty cells will have whatsHere set to the Item::NOTHING. The cells containing the Spellbook, Potion, or Wand will have those fields set to Item::SPELLBOOK, Item::POTION, or Item::WAND, respectively.

Here's an example of how to use Item in relation to a MazeCell*.

void myCoolFunction(MazeCell *cell) {

if (cell->whatsHere == Item::POTION) {

cout << "There's a potion here!" << endl;

}

}

If you were to find yourself in this labyrinth, you could walk around a bit to find the items you need to cast the escape spell. There are many paths you can take; here’s three of them:

ESNWWNNEWSSESWWN

SWWNSEENWNNEWSSEES

WNNEWSSESWWNSEENES

Each path is represented as a sequence of letters (N for north, W for west, etc.) that, when followed from left to right, trace out the directions you’d follow. For example, the first sequence represents going east, then south (getting the Potion), then north, then west, etc. Trace though those paths and make sure you see how they pick up all three items.

There are three milestones to this problem. The first one is a coding problem, and the second two are debugger exercises. We strongly recommend completing them in the order in which they appear, as they build on top of one another.

Milestone One: Check Paths to Freedom

Your first task is to write a function that, given your starting position in the maze and a path, checks whether that path is legal and picks up all three items. Specifically, in the file Labyrinth.cpp, implement the function

bool isPathToFreedom(MazeCell* startLocation, string path);

This function takes as input your starting location in the maze and a string made purely from the characters 'N', 'S', 'E', and 'W', then returns whether that path lets you escape from the maze.

A path lets you escape the maze if (1) the path is legal, in the sense that it never takes a step that isn’t permitted in the current MazeCell, and (2) the path picks up the Spellbook, Wand, and Potion. The order in which those items are picked up is irrelevant, and it’s okay if the path continues onward after picking all the items up.

You can assume that startLocation is not a null pointer (you do indeed begin somewhere) and that the input string does not contain any characters besides 'N', 'S', 'E', and 'W' and do not need to handle the case where this isn’t true.

To summarize, here’s what you need to do.

isPathToFreedom Requirements

-

Implement the

isPathToFreedomfunction inLabyrinth.cpp. -

Test your code thoroughly using our provided tests. (If you’d like to write tests of your own, you’re welcome to do so, though it’s not required here.)

Some notes on this problem:

-

Your code should work for a

MazeCellfrom any possible maze, not just the one shown as an example above. -

Although in the previous picture the maze was structured so that if there was a link from one cell to another going north there would always be a link from the second cell back to the first going south (and the same for east/west links), you should not assume this is the case in this function. Then again, chances are you wouldn’t need to assume this.

-

A path might visit the same location multiple times, including possibly visiting locations with items in them multiple times.

-

You shouldn’t need to allocate any new

MazeCellobjects in the course of solving this problem. Feel free to declare variables of typeMazeCell*, but don’t use thenewkeyword. After all, your job is to check a path in an existing maze, not to make a new maze. -

Feel free to implement this function either iteratively or recursively, whichever seems best to you. You don’t need to worry about stack overflows here; we’ll never run your code on anything large enough to run out of stack space.

-

Your code should not modify the maze passed into the function. In particular, you should not change which items appear where or where the links point.

-

An edge case you should handle: it is okay to find the three items and then continue to walk around the maze. However, if the path both (1) finds all three items and (2) tries making an illegal step, then your function should return false.

Milestone Two: Escape from Your Personal Labyrinth

Your next task is to escape from a labyrinth that’s specifically constructed for you. The starter code we’ve provided will use your name(s) to build you a personalized labyrinth. By “personalized,” we mean “no one else in the course is going to have the exact same labyrinth as you.” Your job is to figure out a path through that labyrinth that picks up all the three items, allowing you to escape.

Open the file LabyrinthEscape.cpp and you’ll see three constants. The first one, MyName, is a spot for your name (or your name and your partner’s name, if you’re working in a pair). Right now, it’s marked with a TODO message. Edit this constant so that it contains your name(s).

Scroll down to the first test case in LabyrinthEscape.cpp. This test case generates a personalized labyrinth based on the MyName constant and returns a pointer to one of the cells in that maze. It then checks whether the constant ThePathOutOfMyMaze is a sequence that will let you escape from the maze. Right now, ThePathOutOfMyMaze is a TODO message, so it’s not going to let you escape from the labyrinth. You’ll need to edit this string with the escape sequence once you find it.

To come up with a path out of the labyrinth, use the debugger! Set a breakpoint at the indicated line in the first test case. Launch the demo app with the debugger enabled. When you do, you should see the local variables window pop up, along with the contents of startLocation, which is the MazeCell where we’ve dropped you into the labyrinth. Clicking the dropdown triangle in the debugger window will let you read the contents of the whatsHere field of startLocation (it’ll be Item::NOTHING), as well as the four pointers leading out of the cell.

Depending on your maze, you may find yourself in a position where you can move in all four cardinal directions, or you may find that you can only move in some of them. The pointers in directions you can’t go are all equal to nullptr, which will show up as 0x0 in the debugger window. The pointers that indicate directions you can go will all have dropdown arrows near them. Clicking one of these arrows will show you the MazeCells reachable by moving in the indicated directions. You can navigate the maze further by choosing one of those dropdown arrows, or you could back up to the starting maze cell and explore in other directions. It’s really up to you!

Draw a lot of pictures. Grab a sheet of paper and map out the maze you’re in. There’s no guarantee where you begin in the maze – you could be in the upper-left corner, dead center, etc. The items are scattered randomly, and you’ll need to seek them out. Once you’ve mapped out the maze, construct an escape sequence and stash it in the constant ThePathOutOfMyMaze, then see if you pass the first test. If so, fantastic! You’ve escaped! If not, you have lots of options. You could step through your isPathToFreedom function to see if one of the letters you entered isn’t what you intended and accidentally tries to move in an illegal direction. Or perhaps the issue is that you misdrew your map and you’ve ended up somewhere without all the items. You could alternatively set the breakpoint at the test case again and walk through things a second time, seeing whether the picture of the maze you drew was incorrect.

To summarize, here’s what you need to do:

Labyrinth Escape Requirements

-

Edit the constant

MyNameat the top ofLabyrinthEscape.cppwith a string containing your name and your partner’s name if you’re working in a group. Don’t skip this step! If you forget to do this, you’ll be solving the wrong maze! -

Set a breakpoint at the indicated line in the first test case in

LabyrinthEscape.cpp, run the program in debug mode, and choose “Run Tests” to activate the breakpoint. -

Map out the maze on a sheet of paper and find where all the items are. Once you’re done, stop the running program.

-

Find a path that picks up all three items and edit the constant

ThePathOutOfMyMazeat the top ofLabyrinthEscape.cppwith that path. Run the test a second time with the debugger turned off to confirm you’ve escaped.

Milestone Three: Escape from Your Personal Twisty Labyrinth

Now, let’s make things a bit more interesting. In the previous section, you escaped from a labyrinth that nicely obeyed the laws of geometry. The locations you visited formed a nice grid, any time you went north you could then go back south, etc.

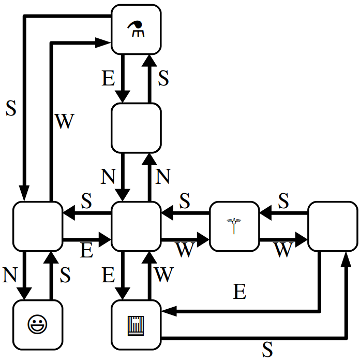

In this section, we’re going to relax these constraints, and you’ll need to find your way out of trickier mazes that look like this one:

This maze is stranger than the previous one you explored. For example, you’ll notice that these MazeCells are no longer in a nice rectangular grid where directions of motion correspond to the natural cardinal directions. There’s a MazeCell here where moving north and then north again will take you back where you started. In one spot, if you move west, you have to move south to return to where you used to be. In that sense, the names “north,” “south,” “east,” and “west” here no longer have any nice geometric meaning; they’re just the names of four possible exits from one MazeCell into another.

The one guarantee you do have is that if you move from one MazeCell to a second, there will always be a direct link from the second cell back to the first. It just might be along a direction of travel that has no relation to any of the directions you’ve taken so far.

The second test case in LabyrinthEscape.cpp contains code that generates a twisty labyrinth personalized with the MyName constant. As before, you’ll need to find a sequence of steps that will let you collect the three items you need to escape.

In many regards, the way to complete this section is similar to the way to complete the previous one. Set a breakpoint in the indicated spot in the second test case and use the debugger to explore the maze. Unlike the previous section, though, in this case you can’t rely on your intuition for what the geometry of the maze will look like. For example, suppose your starting location allows you to go north. You might find yourself in a cell where you can then move either east or west. One of those directions will take you back where you started, but how would you know which one?

This is where memory addresses come in. Internally, each object in C++ has a memory address associated with it. Memory addresses typically are written out in the form @0xsomething, where "something" is the address of the object. You can think of memory addresses as sort of being like an “ID number” for an object – each object has a unique address, with no two objects having the same address. When you pull up the debugger view of a maze cell, you should see the MazeCell memory address under the Value column.

For example, suppose that you’re in a maze and your starting location has address 0x7fffc8003740 (the actual number you see will vary based on your OS), and you can move to the south (which ways you can go are personalized to you based on your name, so you may have some other direction to move). If you expand out the dropdown for the south pointer, you’ll find yourself at some other MazeCell. One of the links out of that cell takes you back where you’ve started, and it’ll be labeled 0x7fffc8003740. Moving in that direction might not be productive – it just takes you back where you came from – so you’d probably want to explore other directions to search the maze.

It’s going to be hard to escape from your maze unless you draw lots of pictures to map out your surroundings. To trace out the maze that you’ll be exploring, we recommend diagramming it on a sheet of paper as follows. For each MazeCell, draw a circle labeled with the memory address, or, at least the last five characters of that memory address. (Usually, that’s sufficient to identify which object you’re looking at). As you explore, add arrows between those circles labeled with which direction those arrows correspond to. What you have should look like the picture above, except that each circle will be annotated with a memory address. It’ll take some time and patience, but with not too much effort you should be able to scout out the full maze. Then, as before, find an escape sequence from the maze!

To recap, here's what you need to do:

Twisty Labyrinth Escape Requirements

-

Set a breakpoint at the indicated line in the second test case in

LabyrinthEscape.cpp, run the demo app in debug mode and choose “Run Tests” to activate the breakpoint. -

Map out the twisty maze on a sheet of paper and find where all the items are and how the cells link to each other. Once you’re done, stop the running program.

-

Find an escape sequence, and edit the constant

ThePathOutOfMyTwistyMazeat the top ofLabyrinthEscape.cppwith that constant. Run the tests again – this time without the breakpoint – and see if you’ve managed to escape!

Some notes on this problem:

-

The memory addresses of objects are not guaranteed to be consistent across runs of the program. This means that if you map out your maze, stop the running program, and then start the program back up again, you are not guaranteed that the addresses of the

MazeCells in the maze will be the same. The shape of the maze is guaranteed to be the same, though. If you do close your program and then need to explore the maze again, you may need to relabel your circles as you go, but you won’t be drawing a different set of circles or changing where the arrows link. -

You are guaranteed that if you follow a link from one

MazeCellto another, there will always be a link from that secondMazeCellback to the first, though the particular directions of those links might be completely arbitrary. That is, you’ll never get “trapped” somewhere where you can move one direction but not back where you started. -

Attention to detail is key here – different

MazeCellobjects will always have different addresses, but those addresses might be really similar to one another. Make sure that as you’re drawing out your diagram of the maze, you don’t include duplicate copies of the sameMazeCell. -

The maze you’re exploring might contain loops or cases where there are multiple distinct paths between different locations. Keep this in mind as you’re exploring or you might find yourself going in circles!

-

Remember that you don’t necessarily need to map out the whole maze. You only need to explore enough of it to find the three items and form a path that picks all of them up.

At this point, you have a solid command of how to use the debugger to analyze linked structures. You know how to recognize a null pointer, how to manually follow links between objects, and how to reconstruct the full shape of the linked structure even when there’s bizarre and unpredicable cross-links between them. We hope you find these skills useful as you continue to write code that works on linked lists and other linked structures!