Stacks and Queues

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2023, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Announcements

- Section starts this week! Section assignments were released yesterday, please check your email for your time assignment and room information.

- If you have not yet signed up for a section, or you can no longer make your assigned section time, you can go to the CS198 Website and add yourself to any section that has an open spot. If you can't make any of the remaining section times, reach out to Neel.

- Assignment 1 is due on Friday! Assignment 2 will be released shortly after.

Slide 2

Abstract Data Types

- We are about to discuss two new containers in which to store our data: the stack and queue containers. These are also known as abstract data types, meaning that we are defining the interface for a container, and how it is actually implemented under the hood is not of our concern (at this point!)

- An abstract data type is defined by its behavior from the point of view of the user of the data, and by the operations it can accomplish with the data.

- The stack and queue containers have similar interfaces, but they are used for very different problems, as we shall see.

Slide 3

Stacks

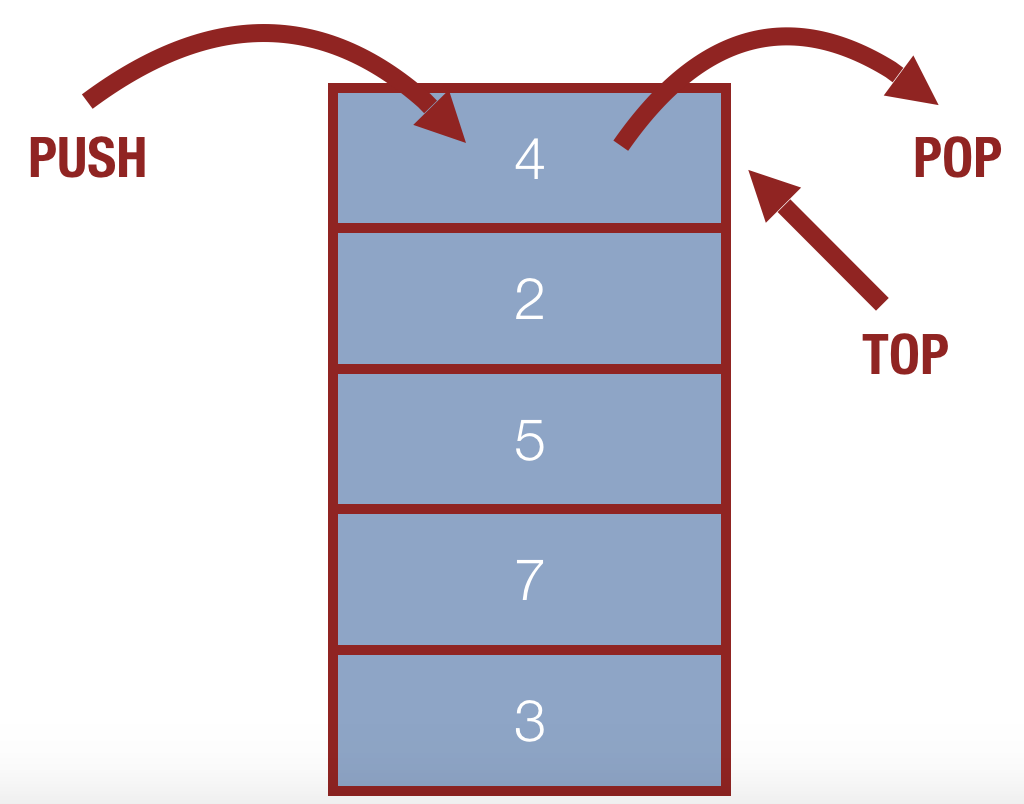

A stack is an abstract data type with the following behaviors / functions:

push(value)- add an element onto the top of the stackpop()- remove the element from the top of the stack and return itpeek()- look at the element at the top of the stack, but don’t remove itisEmpty()- a boolean value,trueif the stack is empty,falseif it has at least one element. (note: a runtime error occurs if apop()orpeek()operation is attempted on an empty stack.)

Why do we call it a stack? Because we model it using a stack of things:

- The

push,pop, andpeekoperations are the only operations allowed by the stack ADT, and as such, only the top element is accessible. Therefore, a stack is a Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) structure: the last item in is the first one out of a stack.

Slide 4

Stacks

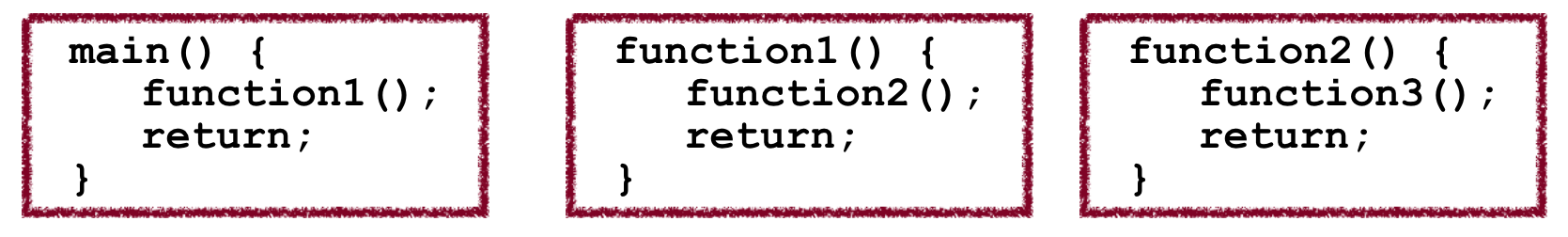

- Despite the stack’s limitations (and indeed, because of them), the stack is a very frequently used ADT. In fact, most computer architectures implement a stack at the very core of their instruction sets – both push and pop are assembly code instructions.

- Stack operations are so useful that there is a stack built in to every program running on your PC — the stack is a memory block that gets used to store the state of memory when a function is called, and to restore it when a function returns.

- Why are stacks used when functions are called?

- Let's say we had a program like this:

maincallsfunction1, which callsfunction2, which callsfunction3.- First,

function3returns, thenfunction2returns, thenfunction1returns, thenmainreturns. - This is a LIFO pattern!

- Let's say we had a program like this:

Slide 5

Stacks: Tradeoffs

- What re some downsides to using a stack?

- No random access. You get the top, or nothing.

- No walking through the stack at all — you can only reach an element by popping all the elements higher up off first

- No searching through a stack.

- What are some benefits to using a stack?

- Useful for lots of problems – many real-world problems can be solved with a Last-In-First-Out model (we'll see one in a minute)

- Very easy to build one from an array such that access is guaranteed to be fast.

- Where would you have the top of the stack if you built one using a Vector? Why would that be fast?

Slide 6

Reversing the words in a sentence

- Let's build a program from scratch that reverses the words in a sentence.

- Goal: reverse the words in a sentence that has no punctuation other than letters and spaces.

- How might we do this?

- Use a stack

- Read characters in a string and place them in a new word.

- When we get to a space, push that word onto the stack, and reset the word to be empty.

- Repeat until we have put all the words into the stack.

- Pop the words from the stack one at a time and print them out.

Slide 7

Reversing the words in a sentence with a stack

#include <iostream>

#include "console.h"

#include "stack.h"

using namespace std;

const char SPACE = ' ';

int main() {

string sentence = "hope is what defines humanity";

string word;

Stack<string> wordStack;

cout << "Original sentence: " << sentence << endl;

for (char c : sentence) {

if (c == SPACE) {

wordStack.push(word);

word = ""; // reset

} else {

word += c;

}

}

if (word != "") {

wordStack.push(word);

}

cout << " New sentence: ";

while (!wordStack.isEmpty()) {

word = wordStack.pop();

cout << word << SPACE;

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

Output:

Original sentence: hope is what defines humanity

New sentence: humanity defines what is hope

Slide 8

Next…

Slide 9

Queues

- The next ADT we are going to talk about is a queue. A queue is similar to a stack, except that (much like a real queue/line), it follows a "First-In-First-Out" (FIFO) model:

- The first person in line is the first person served.

- The last person in line is the last person served.

- Insertion into a queue

enqueue()is done at the back of the queue, and removal from a queuedequeue()is done at the front of the queue.

Slide 10

Queues

- Like the stack, the queue Abstract Data Type can be implemented in many ways (we will talk about some later!). A queue must implement at least the following functions:

enqueue(value)- add an element onto the back of the queuedequeue()- remove the element from the front of the queue and return itpeek()- look at the element at the front of the queue, but don’t remove itisEmpty()- a boolean value,trueif the queue is empty,falseif it has at least one element. (note: a runtime error occurs if adequeue()orpeek()operation is attempted on an empty queue).

- Example

Queue<int> q; // {}, empty queue q.enqueue(42); // {42} q.enqueue(-3); // {42, -3} q.enqueue(17); // {42, -3, 17} cout << q.dequeue() << endl; // 42 (q is {-3, 17}) cout << q.peek() << endl; // -3 (q is {-3, 17}) cout << q.dequeue() << endl; // -3 (q is {17})

Slide 11

Queue Examples

- There are many real world problems that are modeled well with a queue:

- Jobs submitted to a printer go into a queue (although they can be deleted, so it breaks the model a bit)

- Ticket counters, supermarkets, etc.

- File server - files are doled out on a first-come-first served basis

- Call centers (“your call will be handled by the next available agent”)

- The LaIR is a queue!

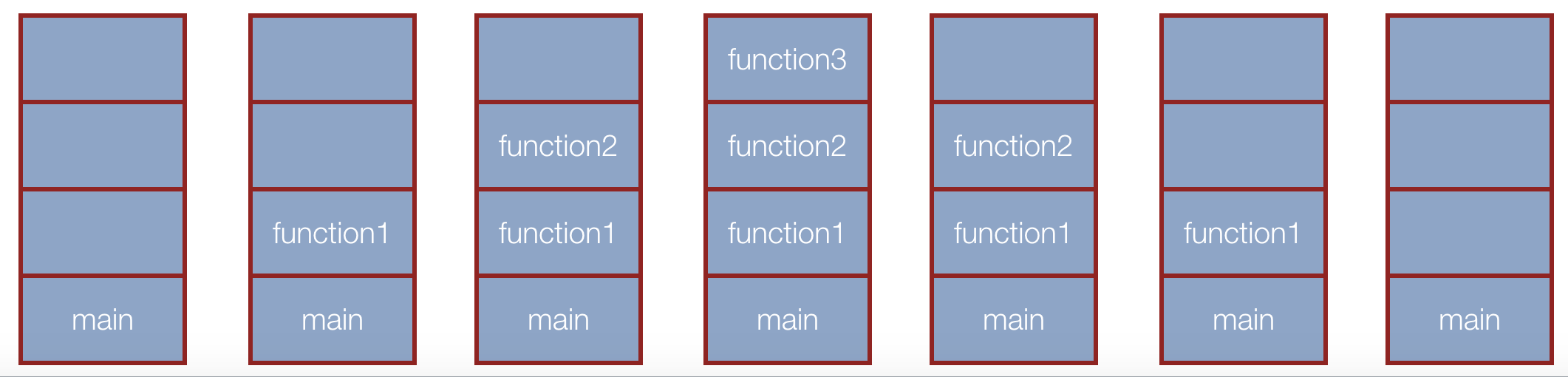

- Chris G’s research! Scheduling work between a CPU and a GPU is queue based.

Actual slide from Chris's Ph.D. dissertation defense:

Slide 12

Queue Mystery

-

Both the Stanford Stack and Queue classes have a

size()function that returns the number of elements in the object. -

What is the output of the following code?

Queue<int> queue; // produce: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} for (int i = 1; i <= 6; i++) { queue.enqueue(i); } for (int i = 0; i < queue.size(); i++) { cout << queue.dequeue() << " "; } cout << queue.toString() << " size " << queue.size() << endl;

A. 1 2 3 4 5 6 {} size 0

B. 1 2 3 {4,5,6} size 3

C. 1 2 3 4 5 6 {1,2,3,4,5,6} size 6

D. none of the above

Answer:

B. 1 2 3 {4,5,6} size 3

- Reason: watch out!

queue.size()changes while the loop runs! You have to be careful when looping and also checking the size of your container.

Slide 13

Queue Idiom 1

- If you are going to empty a stack or queue, a very good programming idiom is the following:

Queue<int> queueIdiom1; // produce: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} for (int i = 1; i <= 6; i++) { queueIdiom1.enqueue(i); } while (!queueIdiom1.isEmpty()) { cout << queueIdiom1.dequeue() << " "; } cout << queueIdiom1.toString() << " size " << queueIdiom1.size() << endl;Output:

1 2 3 4 5 6 { } size 0

Slide 14

Queue Idiom 2

- If you are going to go through a stack or queue once for the original values, a very good programming idiom is the following, which calculates the size of the queue only once:

Queue<int> queueIdiom2; for (int i = 0; i < 6; i++) { queueIdiom2.enqueue(i + 1); } int origQSize = queueIdiom2.size(); for (int i=0; i < origQSize; i++) { int value = queueIdiom2.dequeue(); cout << value << " "; // re-enqueue even values if (value % 2 == 0) { queueIdiom2.enqueue(value); } } cout << endl; cout << queueIdiom2 << endl;Output:

1 2 3 4 5 6 {2, 4, 6} - There will still be three values left in the queue (2, 4, 6), but we only looped through the queue for the original values.

Slide 15

More advanced stack example

-

When you were first learning algebraic expressions, your teacher probably gave you a problem like this, and said, "What is the result?"

5 * 4 - 8 / 2 + 9 - The class got all sorts of different answers, because no one knew the order of operations yet (the correct answer is 25, by the way). Parenthesis become necessary as well (e.g.,

10 / (8-3)). - This is a somewhat annoying problem — it would be nice if there were a better way to do arithmetic so we didn't have to worry about order of operations and parenthesis.

- As it turns out, there is a "better" way! We can use a system of arithmetic called "postfix" notation — the expression above would become the following:

5 4 * 8 2 / - 9 +Wat?

Slide 16

Postfix Example

5 4 * 8 2 / - 9 +

-

Postfix notation* works like this: Operands (the numbers) come first, followed by an operator (+, -, *, /, etc.). When an operator is read in, it uses the previous operands to perform the calculation, depending on how many are needed (most of the time it is two).

-

So, to multiply 5 and 4 in postfix, the postfix is

5 4 *To divide 8 by 2, it is8 2 / -

There is a simple and clever method using a stack to perform arithmetic on a postfix expression:

- Read the input and push numbers onto a stack until you reach an operator.

- When you see an operator, apply the operator to the two numbers that are popped from the stack.

- Push the resulting value back onto the stack.

- When the input is complete, the value left on the stack is the result.

*Postfix notation is also called "Reverse Polish Notation" (RPN) because in the 1920s a Polish logician named Jan Łukasiewicz invented "prefix" notation, and postfix is the opposite of postfix, and therefore so-called "Reverse Polish Notation"

Slide 17

Postfix Example Code

// Postfix arithmetic, implementing +, -, *, /

#include "console.h"

#include "simpio.h"

#include "stack.h"

#include "strlib.h"

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

const char SPACE = ' ';

const string OPERATORS = "+-*x/";

const string SEPARATOR = " ";

double parsePostfix(string expression);

string getNextToken(string &expression);

void performCalculation(Stack<double> &s, char op);

int main() {

string expression;

double answer;

do {

expression =

getLine("Please enter a postfix expression (blank to quit): ");

if (expression == "") {

break;

}

answer = parsePostfix(expression);

cout << "The answer is: " << answer << endl << endl;

} while (true);

return 0;

}

string getNextToken(string &expression) {

// pull out the substring up to the first space

// and return the token, removing it from the expression

string token;

int sepLoc = expression.find(SEPARATOR);

if (sepLoc != (int)string::npos) {

token = expression.substr(0, sepLoc);

expression = expression.substr(sepLoc + 1, expression.size() - sepLoc);

return token;

} else {

token = expression;

expression = "";

return token;

}

}

double parsePostfix(string expression) {

Stack<double> s;

string nextToken;

while (expression != "") {

// gets the next token and removes it from expression

nextToken = getNextToken(expression);

if (OPERATORS.find(nextToken) == string::npos) {

// we have a number

double operand = stringToDouble(nextToken);

s.push(operand);

} else {

// we have an operator

char op = stringToChar(nextToken);

performCalculation(s, op);

}

}

return s.pop();

}

void performCalculation(Stack<double> &s, char op) {

double result;

double operand2 = s.pop(); // LIFO!

double operand1 = s.pop();

switch (op) {

case '+':

result = operand1 + operand2;

break;

case '-':

result = operand1 - operand2;

break;

// allow "*" or "x" for times

case '*':

case 'x':

result = operand1 * operand2;

break;

case '/':

result = operand1 / operand2;

break;

}

s.push(result);

}

Example run:

Please enter a postfix expression (blank to quit): 5 4 * 8 2 / - 9 +

The answer is: 25

Please enter a postfix expression (blank to quit): 1 2 3 4 + + +

The answer is: 10

Please enter a postfix expression (blank to quit): 1 2 3 4 - - -

The answer is: -2

Please enter a postfix expression (blank to quit): 1 2 + 3 * 6 + 2 3 + /

The answer is: 3

Please enter a postfix expression (blank to quit): 2 3 4 + * 6 -

The answer is: 8

Slide 18

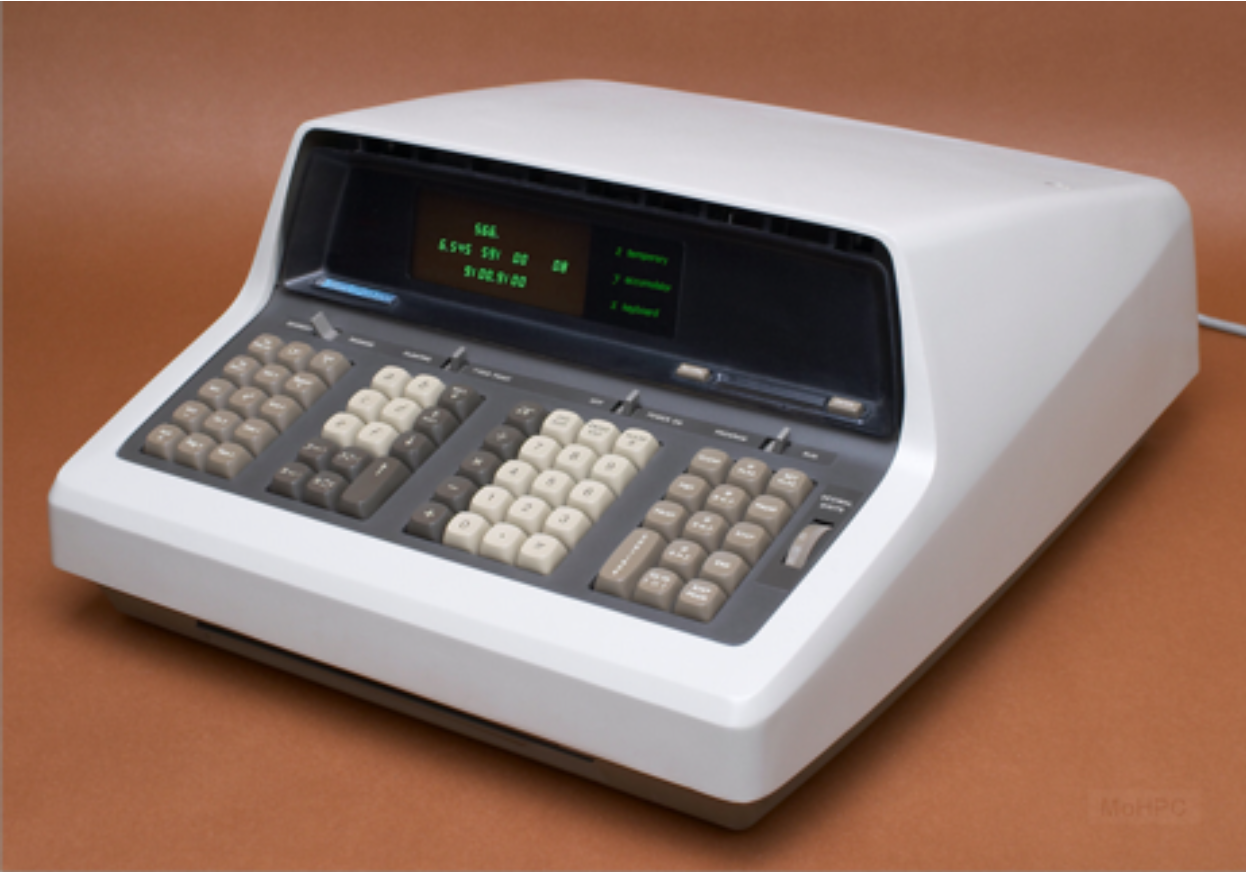

World's First Programmable Desktop Computer

- The HP 9100A Desktop Calculator: the world’s first programmable scientific desktop computer — really, the first desktop computer. (Wired, Dec. 2000)

- RPN (postfix)

- Special algorithm for trigonometric and logarithmic functions

- Cost $5000 in 1968 ($41,000 today)