Introduction to Recursion

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2023, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Slide 2

Announcements

- Assignment 2 is due Friday, end of day PDT.

- Add/drop deadline is on Friday – feel free to reach out to the course staff if you have any questions about the class going forward.

Slide 3

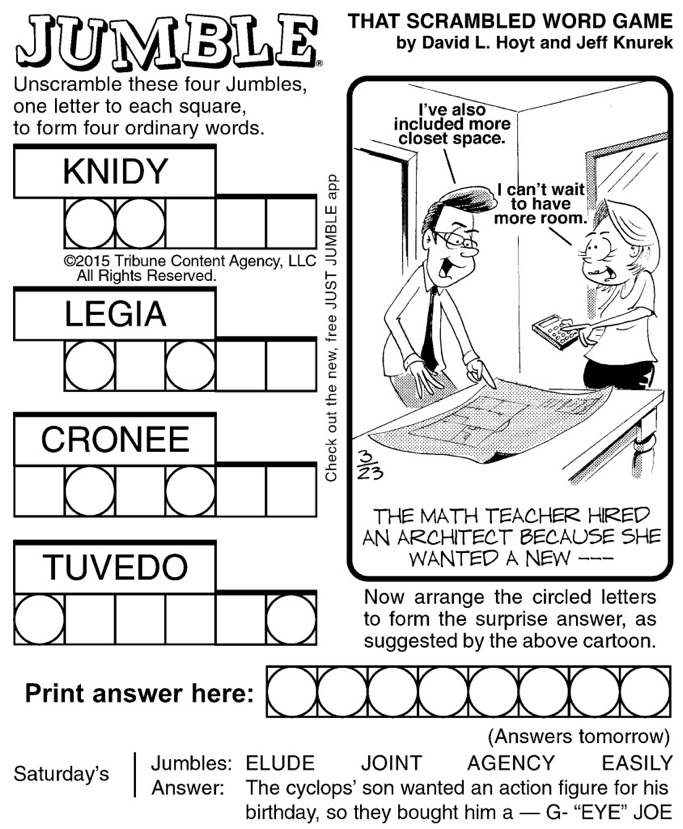

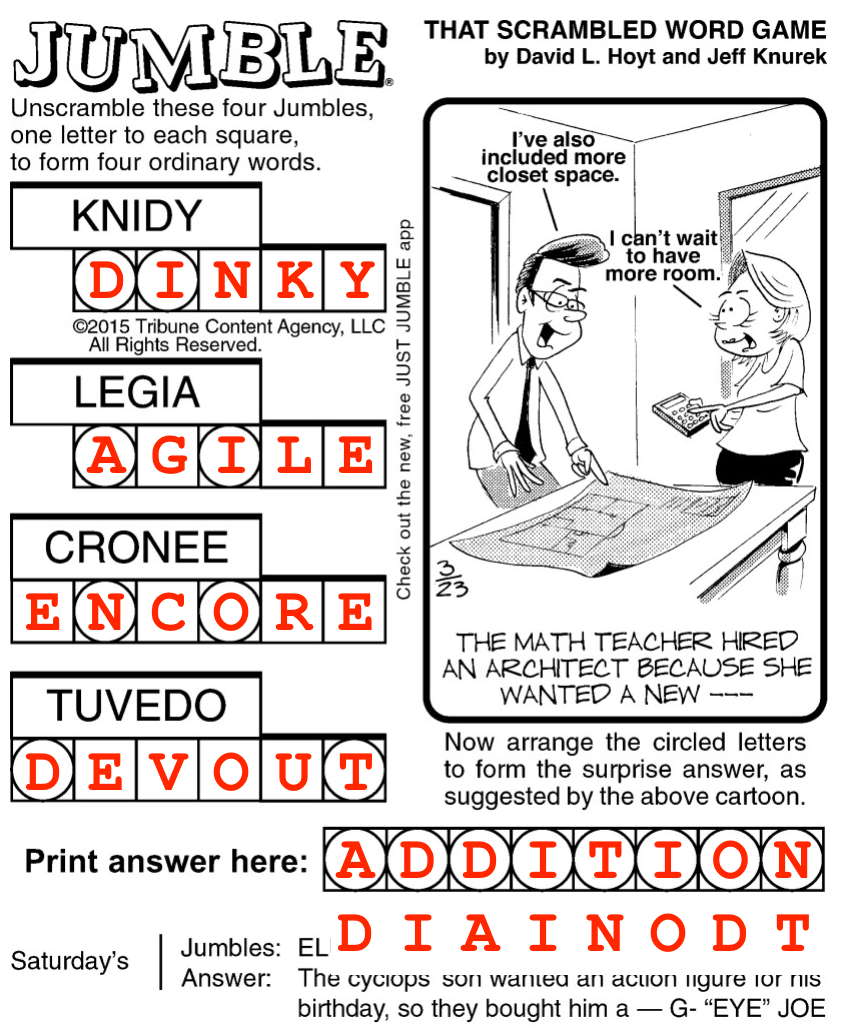

- Since 1954, the JUMBLE has been a staple in newspapers.

- The basic idea is to unscramble the anagrams for the words on the left, and then use the letters in the circles as another anagram to unscramble to answer the pun in the comic.

- As a kid, I played the puzzle every day, but some days I just couldn't descramble the words. Six letter words have 6! == 720 combinations, which can be tricky!

-

I figured I would write a computer program to print out all the permutations!

- Solution:

Slide 4

Permutations – the wrong way

- My original function to print out the permutations of four letters:

void permute4(string s) { for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < 4 ; j++) { if (j == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) { if (k == j or k == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int w = 0; w < 4; w++) { if (w == k or w == j or w == i) { continue; // ignore } cout << s[i] << s[j] << s[k] << s[w] << endl; } } } } } - I also had a

permute5()function:void permute5(string s) { for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < 5 ; j++) { if (j == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { if (k == j or k == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int w = 0; w < 5; w++) { if (w == k or w == j or w == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int x = 0; x < 5; x++) { if (x == k or x == j or x == i or x == w) { continue; } cout << " " << s[i] << s[j] << s[k] << s[w] << s[x] << endl; } } } } } }

- And I had a

permute6()function…void permute6(string s) { for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < 5 ; j++) { if (j == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { if (k == j or k == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int w = 0; w < 5; w++) { if (w == k or w == j or w == i) { continue; // ignore } for (int x = 0; x < 5; x++) { if (x == k or x == j or x == i or x == w) { continue; } for (int y = 0; y < 6; y++) { if (y == k or y == j or y == i or y == w or y == x) { continue; } cout << " " << s[i] << s[j] << s[k] << s[w] << s[x] << s[y] << endl; } } } } } } }

- This is not tenable!

-

In the Linux kernel coding style guide (mostly written by Linus Torvalds, himself), indentations are 8 spaces, which is a lot. This is what the guide says:

Now, some people will claim that having 8-character indentations makes the code move too far to the right, and makes it hard to read on a 80-character terminal screen. The answer to that is that if you need more than 3 levels of indentation, you’re screwed anyway, and should fix your program. [source]

- We can take this to heart and say that our permutation-by-looping methods above are not a good idea.

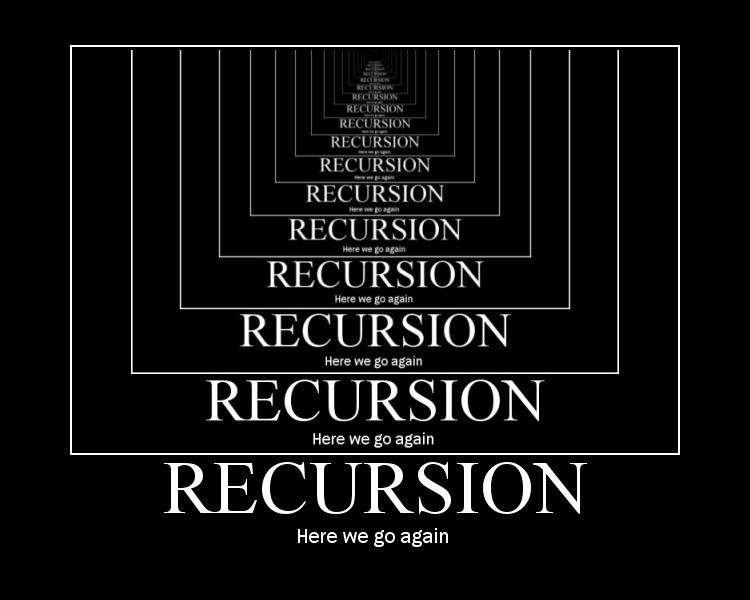

What is Recursion?

- Recursion is: A problem solving technique in which problems are solved by reducing them to smaller problems of the same form.

Slide 5

Why Recursion?

- It's a powerful tool for certain problems

- It's an elegant way to provide control flow

- We have many simple examples of recursion

Slide 6

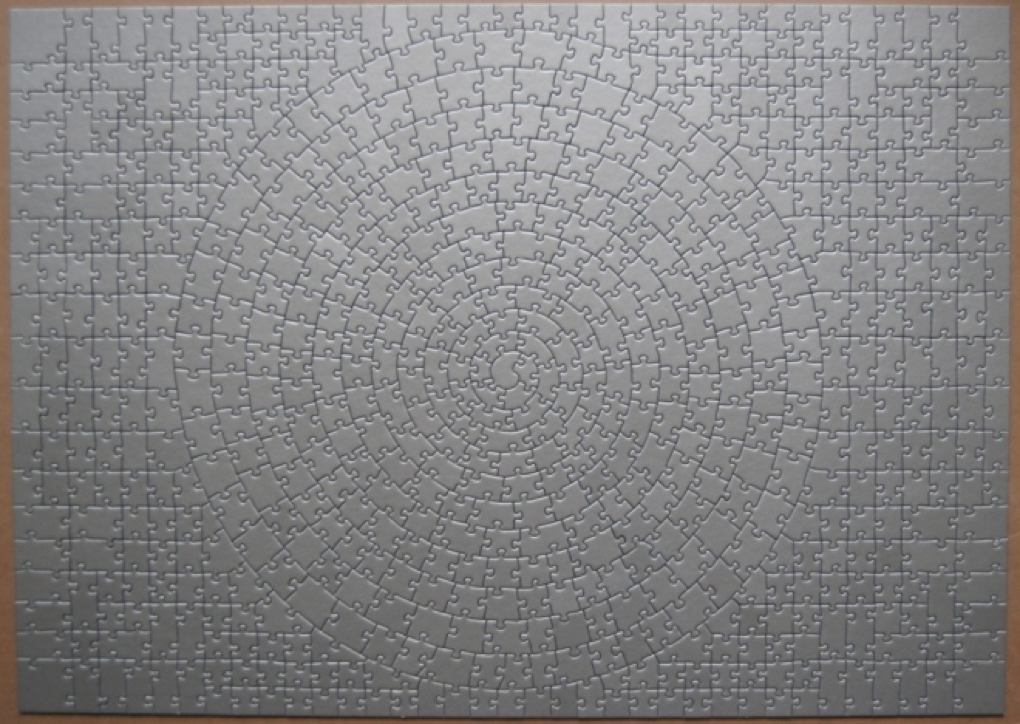

Recursion in Real Life

(Ridiculously hard puzzle)

(Ridiculously hard puzzle)

- How to solve a jigsaw puzzle recursively ("solve the puzzle")

- Is the puzzle finished? If so, stop.

- Find a correct puzzle piece and place it.

- Solve the puzzle

Slide 7

Counting people…recursively

-

Let's try something. Let's perform a little algorithm to count the nuber of people in a column in the lecture hall. We'll start with one person at the bottom of the column, and then the next person will be behind them, all the way to the top. Eventually, the last person won't have anyone else to their right. Let's run the algorithm as follows:

- A person can see and talk only to the people directly in front or back of them. In other words, the first person cannot just simply count the number of people – everyone has to be involved.

- When a person gets asked "how many people are there?" they look behind them. If there is no one there (i.e., they are the last person), then they will reply, "1".

- If there is a person there, they ask that person the same question, and then wait for an answer.

- Once a person gets a reply, they will add one to the number they just heard, and say the new number. So, the person second from last will hear "1" and then turn to the prior person and say "2". The next person will hear "2" and then say "3" to the prior person to them. This will continue all the way back to the beginning.

- At the end, we should have the number of people in the group! Let's see how we do…

Slide 8

Recursion in Programming

- In programming, recursion simply means that a function will call itself.

- Here is an example. It's a terrible example, for sure (it will crash!), but it is technically recursion:

void recurse() { recurse(); } - Let's see what happens when we run this program…

Slide 9

- Our first recursion just crashed. It wasn't easy to see how many times the function called itself. So, let's have the function actually do something.

void recurse(int counter) {

cout << counter << endl;

recurse(counter + 1);

}

- This example still crashed, but we can at lease see how high the counter will get when we run it. On my machine:

0

1

2

3

...

16698

16699

16700

16701

16702

18:57:59: RecursionCrash/Recursion.app/Contents/MacOS/Recursion crashed.

-

It turns out that this is the infamous stack overflow, because each time we call the

recursefunction, it uses some space on the program stack, and that space (memory) is limited. -

Let's pause for a few minutes before we see some real recursive functions that don't crash.

Slide 10

Recursive Functions

- Every recursive algorithm involves at least two cases:

- the base case: The simple case; an occurrence that can be answered directly; the case that recursive calls reduce to.

- the recursive case: a more complex occurrence of the problem that cannot be directly answered, but can be described in terms of smaller occurrences of the same problem.

Slide 11

The Three "Musts" of Recursion

- Your code must have a case for all valid inputs.

- You must have a base case that does not make recursive calls.

- When you make a recursive call it should be to a simpler instance of the same problem, and make forward progress towards the base case.

Slide 12

Simple Recursion Examples

-

The first real recursion problem we will tackle is a function to raise a number to a power. Specifically, we are going to write a recursive function that takes in a number,

xand an exponent,n, and returns the result ofx^n. - When computing a power, we have the simplest case of

x^0 = 1. -

We also have a way to define a number raised to a power as a simpler form of itself:

x^n = x * x^(n - 1) - By repeatedly performing the simpler calculation, we will eventually get to a power of 0 (assuming that we have a positive power to begin with), and then we can return our

x^0case of1.

Slide 13

Let's code power(x, n)

Slide 14

The power(x, n) function

int power(int x, int n) {

if (n == 0) {

return 1;

} else {

return x * power(x, n - 1);

}

}

- Each previous call waits for the next call to finish (just like any function):

int result = power(5, 3); - The first call is to

power(5, 3)- The second call is to

power(5, 2)- The third call is to

power(5, 1)- The fourth call is to

power(5, 0), which returns 1.

- The fourth call is to

- The third call gets the return value of 1, and returns

5 * 1

- The third call is to

- The second call gets the return value of 5, and returns

5 * 5(25)

- The second call is to

-

The first call gets the return value of 25, and returns

5 * 25(125) -

resultnow holds 125, and this is how recursion works! - You might argue, wait, I could have done that with a loop just as easily, and you would be right. Recursion isn't always the best way to solve a problem, but we will soon see problems that would be very, very hard to do without recursion (we're looking at simple examples now).

Slide 15

More examples! isPalindrome(string s)

- Write a recursive function isPalindrome accepts a string and returns true if it reads the same forwards as backwards.

isPalindrome("madam"); // true isPalindrome("racecar"); // true isPalindrome("step on no pets") // true isPalindrome("python") // false isPalindrome("byebye") // false

Slide 16

Remember: The Three "Musts" of Recursion

- Your code must have a case for all valid inputs.

- You must have a base case that makes not recursive calls.

- When you make a recursive call it should be to a simpler instance of the same problem, and make forward progress towards the base case.

Slide 17

isPalindrome

// Returns true if the given string reads the same

// forwards as backwards.

// Trivially true for empty or 1-letter strings.

bool isPalindrome(string s) {

if (s.length() <= 1) {

// base case: 0- and 1-length strings are always palindromes

return true;

} else if (s[0] != s[s.length() - 1]) {

// base case: first and last characters differ

return false;

}

else {

// recursive case

string middle = s.substr(1, s.length() - 2);

return isPalindrome(middle);

}

}

- Notice that there are two base cases for this function. For strings that are only zero or one characters long, the string is, by definition, a palindrome. For strings that do not have matching beginning and end characters, the string is not a palindrome.

- There is one relatively large flaw with this function, as written. Let's see what would happen for a really long palindrome. Peter Norvig, Distinguished Education Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, and previously a director of research and search quality at Google, wrote a program to create the "worlds longest palindrome". His program created a palindrome that has 21,012 words. If we remove all the punctuation and spaces, we can make this palindrome into something our function can check (and the string has 90,439 characters!).

- When we check what happens, we find that the function crashes, because of the stack overflow problem we saw before!

- This is another function that would have been better to write as a regular loop-based function. We have yet to see a recursive function that cannot be written this way!

- Note: There is a way around the problem for our recursive function, but it is beyond the scope of this class: tail call optimization is the ability for a compiler to recognize that the last call in a recursive function simply calls the function, and it can convert the algorithm into one that is not recursive, and won't suffer from stack overflows. In C++, we would need to make one change to our program: we would need to use

string_view(an immutable string) in place ofstring, because of some nuances of thestringclass. We would also have to ensure that we tell the compiler to perform the optimization. If you want more information about this, see me after class!

Slide 18

Permutations: the recursive way

- As we saw at the beginning of the lecture, permutations do not lend themselves well to iterative looping because we are really rearranging the letters, which doesn't follow an iterative pattern.

- Instead, we can look at a recursive method to do the rearranging, called an exhaustive algorithm. We want to investigate all possible solutions. We don't need to know how many letters there are in advance!

- In English:

- The permutation starts with zero characters, as we have all the letters in the original string to arrange. The base case is that there are no more letters to arrange.

- For all the letters in the string, take one letter and add it to the current permutation, and recursively continue the process, decreasing the characters left by one.

- In pseudocode:

If you have no more characters left to rearrange, print the current permutation for (every possible choice among the characters left to rearrange) { Make a choice and add that character to the permutation so far Use recursion to rearrange the remaining letters }

Slide 19

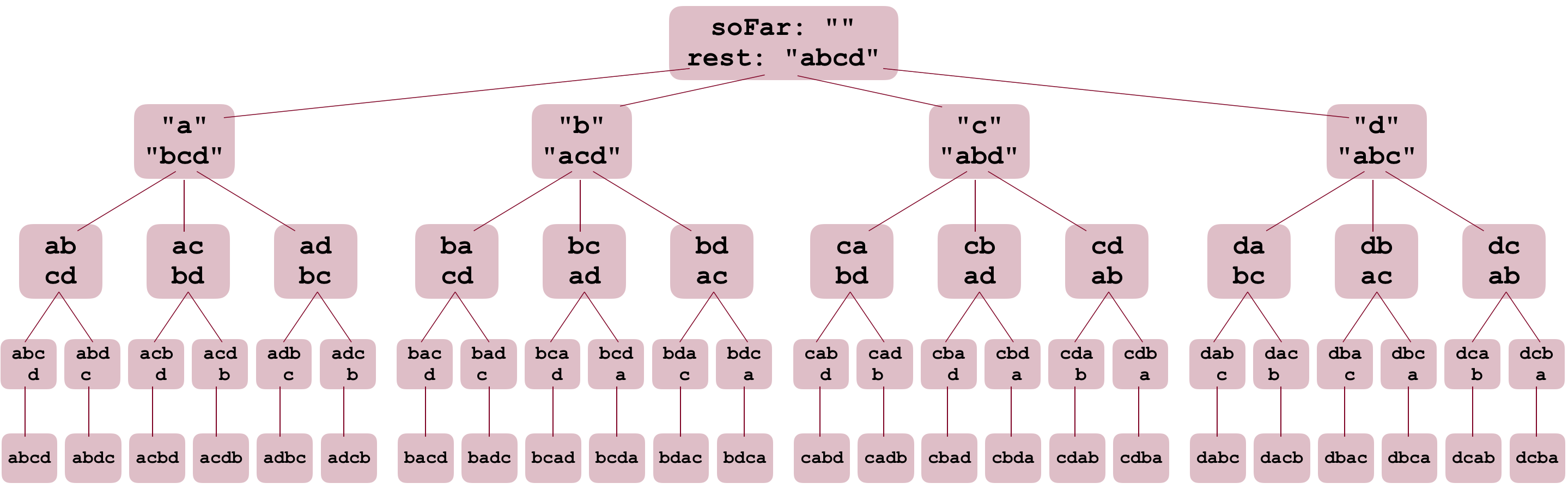

The search tree

- This is a permutation tree, which is very similar to the decision tree: it is an upside down tree, actually, with the root at the top of the diagram, and the leaves at the bottom. At each stage, the tree branches to form more parts of the permutation.

- In the first iteration of the function,

soFarfirst becomesa, andrestbecomesbcd. Likewise for the second iteration:soFarbecomesbandrestbecomesacd. -

If we follow the left branch all the way down, you can see that

soFarkeeps getting updated, andrestgets smaller. In fact, you should notice in the last row that the order of the output we got on the last slide was the same as this diagram – this happens because the first call topermutekeeps recursing all the way toabcd, and then the prior branch (ab,cd) also has to branch toabd,candabdcbefore returning up toaandbcd. Doing this tracing on the diagram can be super important to understanding how the recursion is progressing. - In C++:

void permute(string soFar, string rest) { if (rest == "") { cout << soFar << endl; return; } for (int i = 0; i < rest.length(); i++) { // remove character we are on from rest string remaining = rest.substr(0, i) + rest.substr(i+1); permute(soFar + rest[i], remaining); } } - Example call:

permute("", "abcd");

- Output:

abcd abdc acbd acdb adbc adcb bacd badc bcad bcda bdac bdca cabd cadb cbad cbda cdab cdba dabc dacb dbac dbca dcab dcba

Slide 20

Recursion Recap

- Break a problem into smaller subproblems of the same form, and call the same function again on that smaller form.

- Super powerful programming tool Not always the perfect choice, but often a good one

-

Some beautiful problems are solved recursively

- Three Musts for Recursion:

- Your code must have a case for all valid inputs

- You must have a base case that makes no recursive calls

- When you make a recursive call it should be to a simpler instance and make forward progress towards the base case.