Procedural Recursion

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2023, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Slide 2

Announcements

- Assignment 3 is due Friday

- Note: the assignment is actually due Friday. Everyone has an automatic extension until Saturday, though if you turn it in then you won't get the on-time bonus. What this means is that if you ask for an extension, you've already got a 1-day extension. So, don't be too surprised if Neel and I don't give you more time.

Slide 3

Today's Goals:

- Today and next time, we want to discuss how to use recursion to perform an exhaustive exploration of a search space.

- The examples we will cover:

- generating sequences from a set of choices

- generating all subsets

Slide 4

Templates for recursive functions

- There are basically five different problems you might see that will require the kind of recursion we are transitioning to:

- Determine whether a solution exists

- Find a solution

- Find the best solution

- Count the number of solutions

- Print/find all the solutions

- We are going to focus today on the last item, printing and finding all solutions.

Slide 5

Generating sequences

Let's say you flip a coin twice. What are the possible sequences that might result? A little human brainstorming can come up with the four possibilities:

H H

H T

T H

T T

What about a sequence of three coin flips or four? If we try to manually enumerate these longer sequences, how can we be sure we got them all and didn't repeat any? It will help to take a systematic approach.

Consider: how does a length N sequence build upon the length N-1 sequences? If we take each of the above length 2 sequences and paste an H or T on the front, we will generate all the length 3 sequences. We can do something similar to extend from length 3 to length 4 and so on. This indicates a self-similarity in the problem that should lend itself nicely to being solved recursively.

H H H

H H T

H T H

H T T

T H H

T H T

T T H

T T T

Slide 6

Decision trees

Let's create a visualization of the search space for coin flips. We model the choices and where each leads using a diagram called a decision tree.

Each decision is one flip, and the possibilities are heads or tails. A sequence of N flips has N such choices.

The top of the tree is the first choice with its possibilities underneath:

|

+--------+--------+

| |

H T

Each choice we make leads to a different part of the search space. From there, we consider the remaining choices. Below is a decision tree for the first two flips:

|

+--------+---------+

| |

H T

| |

+------+------+ +-----+------+

| | | |

HH HT TH TT

The height of the tree corresponds to the number of decisions we have to make. The width at each decision point corresponds to the number of options. To exhaustively explore the entire search space, we must try every possible option for every possible decision. That can be a lot of paths to walk!

Next let's write a function to generate these sequences. This code traverses the entire decision tree. By using recursion, we are able to capitalize on the self-similar structure.

void generateSequences(int length, string soFar)

{

if (length == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

} else {

generateSequences(length - 1, soFar + " H");

generateSequences(length - 1, soFar + " T");

}

}

Note that the recursive case makes two recursive calls. The first call recursively explores the left arm of the decision tree (having chosen "H"), the second explores the right arm (having chosen "T").

This function prints all possible 2^N sequences. If you extend the sequence length from N to N + 1, there are now twice as many sequences printed. It first prints the complete set of the sequences of length N each with an "H" pasted in front, followed by a repeat of the sequences of length N now with an "T" pasted in front.

Next we changed the search space. In place of flipping a coin, we will choose letter from the alphabet. The code changes only slightly (though it is ugly!):

void generateLetterSequencesUgly(int length, string soFar)

{

if (length == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

} else {

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'A');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'B');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'C');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'D');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'E');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'F');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'G');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'H');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'I');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'J');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'K');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'L');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'M');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'N');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'O');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'P');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'Q');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'R');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'S');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'T');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'U');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'V');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'W');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'X');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'Y');

generateLetterSequencesUgly(length - 1, soFar + 'Z');

}

}

Can we fix this code so that it isn't so tedious? This is a CS 106A question! A loop is just the thing to compactly express iterating over the alphabet:

void generateLetterSequencesNice(int length, string soFar)

{

if (length == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

} else {

for (char ch = 'A'; ch <= 'Z'; ch++) {

generateLetterSequencesNice(length - 1, soFar + ch);

}

}

}

Using both iteration and recursion in combo may be a bit puzzling. In some of our previous examples, recursion was used as an alternative to iteration, but in this case, both are working together. The iteration is used to enumerate the options for a given single choice. Once an option is picked in the loop, recursion is used to explore subsequent choices from there. In terms of the decision tree, iteration is traversing horizontally and recursion is traversing vertically.

Slide 7

Helper functions for recursive functions

- We've gone over the

permutefunction already. Here is thepermutecode again:void permute(string soFar, string rest) { if (rest == "") { cout << soFar << endl; } else { for (int i = 0; i < rest.length(); i++) { string remaining = rest.substr(0, i) + rest.substr(i+1); permute(soFar + rest[i], remaining); } } } - Some might argue that this isn't a particularly good function, because it requires the user to always start the algorithm with the empty string for the

soFarparameter. It's ugly, and it exposes our internal parameter. - What we really want is a

permute(string s)function that is cleaner. - In C++, we can overload the

permute()function with one parameter and have a cleaner permute function that calls the original one with two parameters:void permute(string s) { permute("", s); } - Note that this function has the same name as the original – this is legal in C++ as long as the compiler can differentiate the two by their (different) parameters.

-

Now, a user only has to call

permute("tuvedo"), which hides the recursion parameter. -

Often, we don't use the same name, because it does get confusing. So, we might have renamed the two-argument

permutefunctionpermuteHelperand then calledpermuteHelper(soFar + rest[i], remaining). - What usually happens with helper functions is that we start with a function that we want to solve recursively, and then we realize that we don't have enough parameters to solve it, so we create the helper function with the necessary parameters. In other words, if you were asked to write a recursive

permute(string s)function, you would create the helper function,permuteHelper(string soFar, string rest)to do it, and then callpermuteHelper("", s)frompermute().

Slide 8

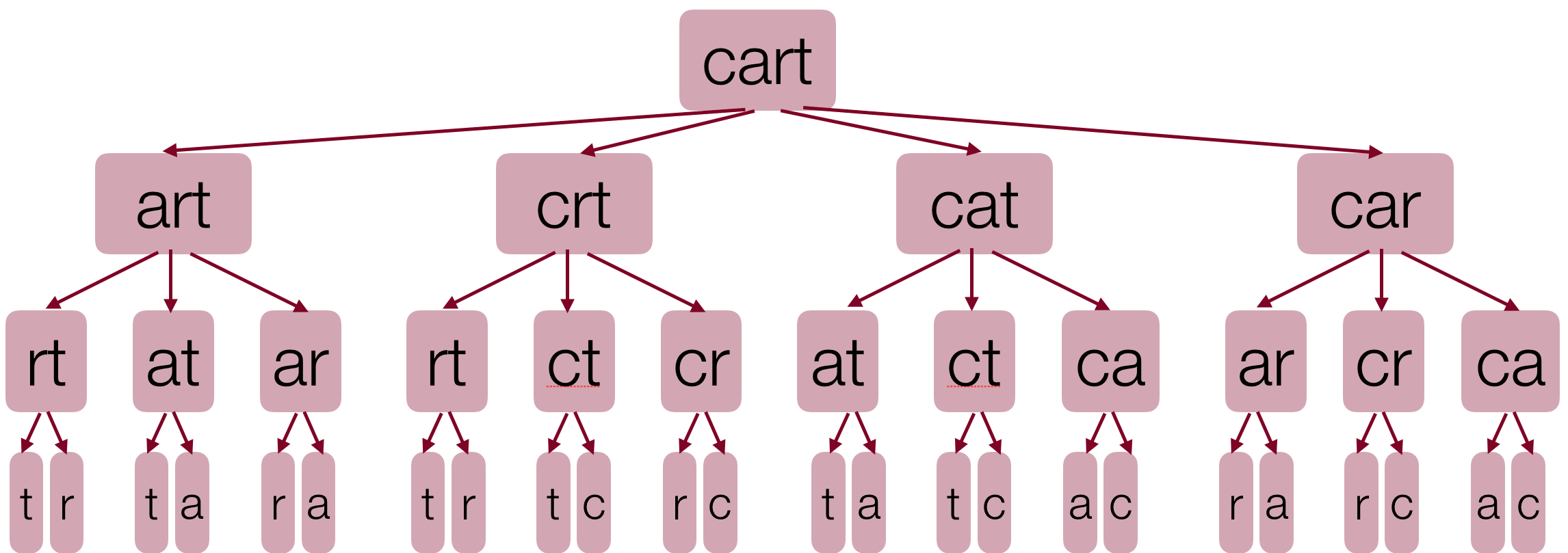

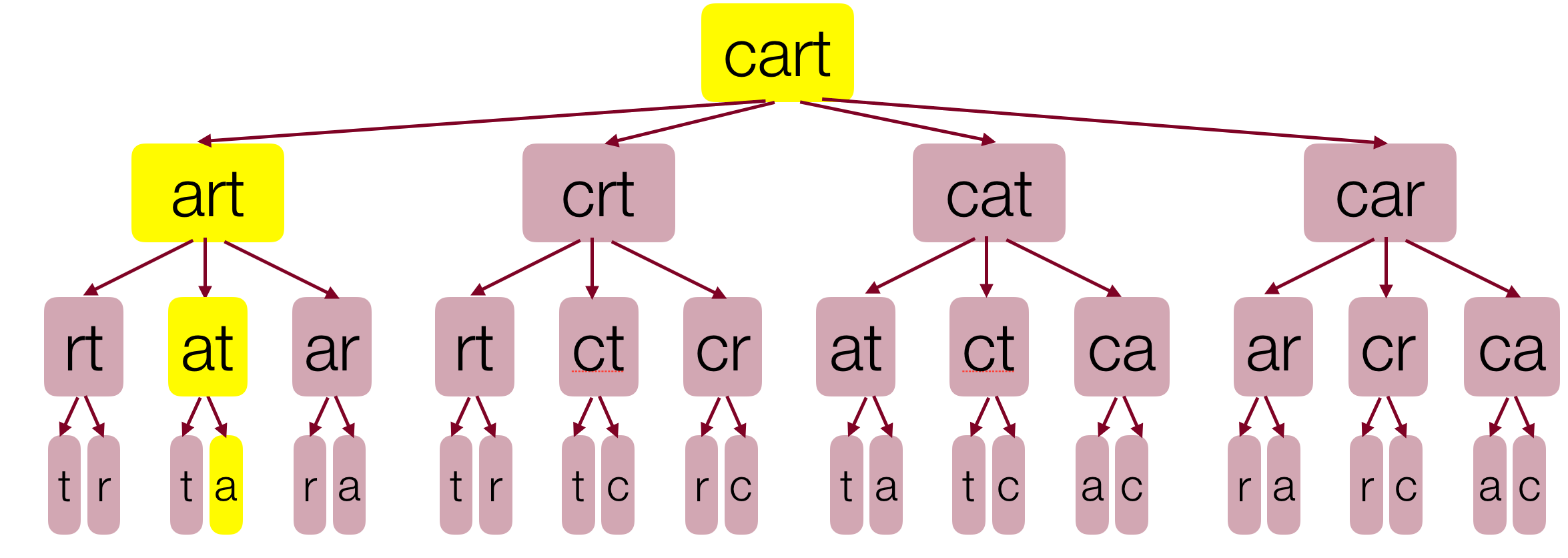

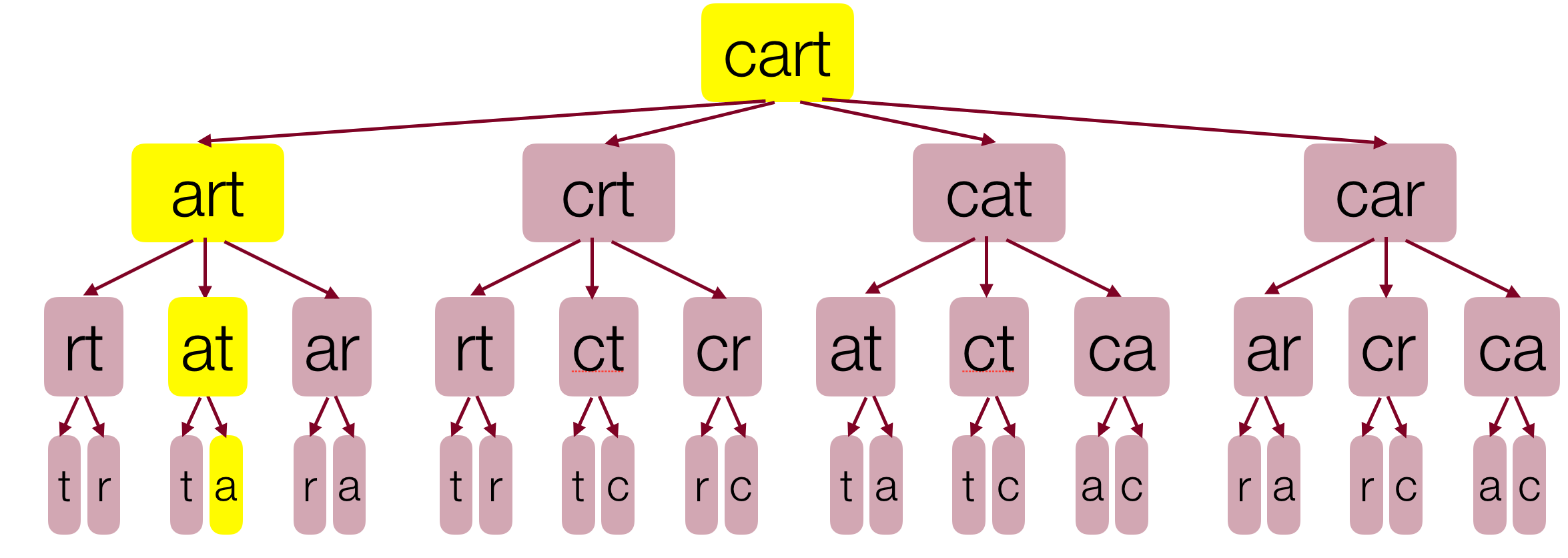

More Decision Trees

- Sometimes with recursion, we want to find out if there we can find a solution among all of the possibilities, but we can stop a particular path once we realize it isn't going to produce a solution. Let's look at an example:

- Here is a word puzzle: "Is there a nine-letter English word that can be reduced to a single-letter word one letter at at time by removing letters, leaving a legal word at each step?" We can call such a word a reducable word.

- 4 letter example:

cart -> art -> at -> a

- Can you think of a 9-letter word?

- 4 letter example:

startling -> starling -> staring -> string -> sting -> sing -> sin -> in -> i

- Is there really just one nine-letter word with this property?

- Could we do this iteratively? Possibly, but it would be messy!

- Can we do this recursively? Yes, with a decision tree!

- Notice that we can find a path through the tree in two different ways:

Slide 9

Decision tree search template

bool search(currentState) {

if (no more moves possible from currentState) {

return isSolution(currentState);

} else {

for (option : moves from currentState) {

nextState = takeOption(curr, option);

if (search(nextState)) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

}

Slide 10

Reducible word

-

Let's define a reducible word as a word that can be reduced down to one letter by removing one character at a time, leaving a word at each step.

- Base case:

- A one letter word in the dictionary.

- Recursive Step:

- Any multi-letter word is reducible if you can remove a letter (legal move) to form a shrinkable word.

- Let's code!

Slide 11

Reducible code

bool reducible(Lexicon & lex, string word) {

// base case

if(word.length() == 1 && lex.contains(word)) {

return true;

}

// recursive case

for(int i = 0; i < (int)word.length(); i++) {

string copy = word;

copy.erase(i, 1);

if(lex.contains(copy)) {

if(reducible(lex, copy)) {

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}