C++ Classes

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2023, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Slide 2

Announcements

- The midterm is Wednesday!

- Assignment 4 will be out on Thursday.

Slide 3

Today's Goals:

- Introduce C++ Classes

- Discuss Object Oriented Programming (OOP)

- Talk about encapsulation as it relates to classes and objects

Slide 4

Introduction to C++ Classes

- We have talked about structs already (briefly), and we'll start with them now. Structs give us the ability to package data into one place. The types of the data do not have to be the same, so we could store strings, ints, bools, etc. We could say that structs are the "Lunchable" of the C++ world – they package different elements together so we can use them together:

struct Lunchable { string meat; string dessert; int numCrackers; bool hasCheese; }; - But why stop at data? If we're packaging stuff up, let's also package up the functions. It would be really nice if we could do this:

struct Lunchable { string meat; string dessert; int numCrackers; bool hasCheese; int countCalories(); // what? A function? }; - Guess what? We **can** do this!

- Once we have the ability to package up data and functions into one structure, we have a super-powerful tool, called an object that knows how to perform functions on itself, and carries around its own data.

- So-called Object Oriented Programming has led to the creation of most of the large programs we use today.

Slide 5

The need for new types

- A C++ "class" is simply a very-slightly modified struct (details to follow).

- As with structs, we sometimes want new types:

- A calendar program might want to store information about dates, but C++ does not have a Date type.

- A student registration system needs to store info about students, but C++ has no Student type.

- A music synthesizer app might want to store information about users' accounts, but C++ has no Instrument type.

Slide 6

Elements of a Class

- member variables: State inside each object.

- Also called "instance variables" or "fields"

- Declared as private

- Each object created has a copy of each field.

- member functions: Behavior that executes inside each object.

- Also called "methods"

- Each object created has a copy of each method.

- The method can interact with the data inside that object.

- constructor: Initializes new objects as they are created.

- Sets the initial state of each new object.

- Often accepts parameters for the initial state of the fields.

Slide 7

The Class Interface Divide

- When building a class, we provide an interface to the user of the class that details how the class works. The user often does not have access to the code itself, but the interface (and any other documentation) usually suffices to use the class properly.

- The interface is generally put into a header file, e.g.,

name.h - The client of the class reads the header file to get the declarations so it can compile its own code to use the class

- The header file shows the class functions and variables (even though some may be private – see post on stack exchange about why)

- The interface is generally put into a header file, e.g.,

- The source code for the class is held in a

.cppfile, e.g.,name.cpp.- The

.cppfile is written by the implementer of the class, and they implement all of the class functions. - This is often delivered to the user in compiled form, or in a library. The client generally does not have or need access to this code (though you can get it for open source code libraries)

- The

Slide 8

Structure of a header file

// classname.h

#pragma once

class ClassName {

// class definition

};

-

The

pragma oncedeclaration basically says, "if you see this file more than once while compiling, ignore it after the first time" (so the compiler doesn't think you're trying to define things more than once) - In more detail:

// in ClassName.h class ClassName { public: ClassName(parameters); // constructor returnType func1(parameters); // member functions returnType func2(parameters); // (behavior inside returnType func3(parameters); // each object) private: type var1; // member variables type var2; // (data inside each object) type func4(); // (private function) }; - Any class instance can directly use anything defined as

public, but you never directly call a constructor. To create an instance of a class, you declare it like this in simple cases (just like declaring a variable):MyClass a; - A client can call all public functions, e.g.,

a.func1(argument) - A class instance cannot directly use anything defined as private:

MyClass a; // declare an instance called "a" a.var1 = 2; // ERROR! "var1" is a private variable a.func4(); // ERROR! "func4" is a private function

Slide 9

Constructors and (eventually) Destructors

// in MyClass.h

class MyClass {

public:

MyClass(); // default constructor

MyClass(parameters); // constructor

...

};

- When a class instance is created, we say that it is constructed:

string s1; // uses default constructor string s2("I'm a string"); // uses a constructor // that takes 1 string parameter string s3 = "I'm a string"; // different! (we'll get to that)

Slide 10

The Implicit Parameter

- The implicit parameter for a class is the object on which the member function is called.

- During the call

chris.withdraw(...), the object namedchrisis the implicit parameter. - During the call

julie.withdraw(...), the object namedjulieis the implicit parameter. - The member function can refer to that object's member variables.

- We say that it executes in the context of a particular object.

- The function can refer to the data of the object it was called on.

- It behaves as if each object has its own copy of the member functions.

- During the call

Slide 11

The this pointer

- In C++ has a

thispointer to refer to the current object (this is similar toselfin Python)- Syntax:

this->member - Common usage: In the constructor, so parameter names can match the names of the object's member variables:

BankAccount::BankAccount(string name, double balance) { this->name = name; this->balance = balance; } thisuses->not.because it is a pointer. We'll discuss pointers soon!

- Syntax:

Slide 12

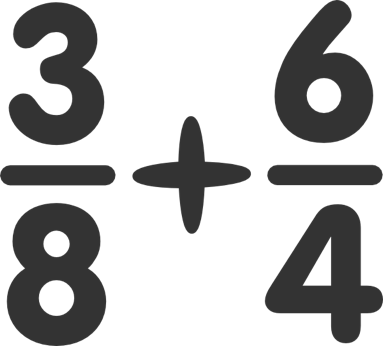

Let's work on an example: the Fraction class

- As an example of a class, we're going to define a

Fractionclass that can deal with rational numbers directly, without decimals. - We are going to walk through the class one step at a time, demonstrating the various parts of a class as we go.

Slide 13

Questions we must answer about the Fraction class

- What data should the class hold?

- What kinds of functions (public / private) should our class have?

- What constructors could we have?

- What is a good value for a default fraction?

Slide 14

Fraction Class Outline

class Fraction {

public:

// Things we want the class clients to see go here

private:

// Things we want to encapsulate from the clients go here

};

- What data should a

Fractionclass have?- A

numeratorand adenominator:class Fraction { public: // Things we want the class clients to see go here private: int num; // the numerator int denom; // the denominator }; - Why are

numanddenomprivate?- We want to encapsulate them

- A

- What functions should a

Fractionclass have?- How about these public functions?

class Fraction { public: void add(Fraction& f); void multiply(Fraction& f); double decimal(); int getNum(); int getDenom(); friend std::ostream& operator<< (std::ostream& out, Fraction& frac); private: int num; // the numerator int denom; // the denominator };

- How about these public functions?

- Why are they public?

- The client can call them directly

- What is this

friendbusiness? And what isoperator<<, etc.?- This defines an operator overload to make it possible to use the

<<operator withcoutfor our class. We will write the function soon.

- This defines an operator overload to make it possible to use the

Slide 15

The Fraction class constructors

- We also need two other functions to construct the class:

class Fraction { public: Fraction(); // the "default" constructor Fraction(int num, int denom); // a second constructor void add(Fraction& f); void multiply(Fraction& f); double decimal(); int getNum(); int getDenom(); friend ostream& operator<< (ostream& out, Fraction& frac); private: int num; // the numerator int denom; // the denominator }; - We have to answer what a default fraction should look like

1/1probably makes sense (but0/0does not!)- We have a constructor to let the client create a fraction of their own choosing, e.g.,

3/4

Slide 16

Private functions

- We might want a couple of other functions that will get used behind the scenes. The client does not need them, so they are private.

- A

reduce()function is useful to keep reduced versions of the fractions - The

reduce()function needs agcd()(greatest common divisor) to do its magic.

- A

class Fraction {

public:

Fraction(); // the "default" constructor

Fraction(int num, int denom); // a second constructor

void add(Fraction& f);

void multiply(Fraction& f);

double decimal();

int getNum();

int getDenom();

friend ostream& operator<< (ostream& out, Fraction& frac);

private:

int num; // the numerator

int denom; // the denominator

void reduce();

int gcd(int u, int v);

};

Slide 17

Last but not least…

- We have defined most of our

fraction.hfile, but we do need a couple of things at the top:#pragma once #include<ostream> // for our operator<< overload class Fraction { public: Fraction(); // the "default" constructor Fraction(int num, int denom); // a second constructor void add(Fraction& f); void multiply(Fraction& f); double decimal(); int getNum(); int getDenom(); friend std::ostream& operator<< (std::ostream& out, Fraction& frac); private: int num; // the numerator int denom; // the denominator void reduce(); int gcd(int u, int v); };

Slide 18

The Fraction Class – implementation

- Let's start writing our functions. We do this in our fraction.cpp file, and we have to define the class that each function belongs to. We also cannot forget to include our header file!

#include "fraction.h" -

The default constructor is used when someone wants to just create a default fraction:

Fraction frac; - So, here is the default constructor code:

Fraction::Fraction() { num = 1; denom = 1; } - This is pretty simple! We are just setting our two class variables to default values.

- What is the strange function declaration?

- We need to tell the compiler what class the function belongs to, and we do that with the class name (

Fraction) and the _scope resolutoin operator, two colons,::`. Because the constructor has the same name as the function, we get this funky syntax:Fraction::Fraction()

- We need to tell the compiler what class the function belongs to, and we do that with the class name (

Slide 19

The overloaded constructor

- We also have an overloaded constructor that takes in two values that the user sets. It is called as follows:

// create a // 1/2 fraction Fraction fracA(1,2); // create a // 4/6 fraction Fraction fracB(4,6); - Here is the code:

// purpose: an overloaded constructor // to create a custom fraction // that immediately gets reduced // arguments: an int numerator // and an int denominator Fraction::Fraction(int num, int denom) { this->num = num; this->denom = denom; // reduce in case we were given // an unreduced fraction reduce(); } - Notice that the paramters for our function are the same name as the class variables,

numanddenom.- We must use the

thispointer to set the values so we can differentiate them. Here,thisrefers to whatever instance we have, and it sets the class variables accordingly to the values of the parametesr.

- We must use the

Slide 20

Fraction multiplication

- Let's create a couple of fractions and multiply them:

Fraction fracA(1, 2); Fraction fracB(2, 3); fracA.multiply(fracB); // fracA now holds 1/3 - The code for the

multiplyfunction looks like this:// purpose: to multiply another fraction // with this one, storing the result // in this fraction // arguments: other: another Fraction // return value: none void Fraction::multiply(Fraction& other) { num *= other.num; denom *= other.denom; // reduce the fraction reduce(); }

Slide 21

reduce() and gcd()

- We have two private functions to write that help us multiply.

- The

reduce()function converts our fraction to a reduced one:// purpose: reduce the fraction to lowest terms void Fraction::reduce() { // find the greatest common divisor int frac_gcd = gcd(num,denom); // reduce by dividing num and denom by the gcd num = num / frac_gcd; denom = denom / frac_gcd; } - The

gcd()function is a clever little recursive function that quickly finds the greatest common divisor between two numbers:int Fraction::gcd(int u, int v) { if (v != 0) { return gcd(v, u % v); } else { return u; } }

Slide 22

Fraction decimal value

- The client might want to get the decimal value out of a fraction:

Fraction fracA(1, 2); double f = fracA.decimal(); cout << f << endl;Output:

0.5 - The code for

decimalis pretty simple:// purpose: to return the decimal value for this fraction // return value: a double representing the decimal value double Fraction::decimal() { return (double) num / denom; // must cast at least one value } - We have to cast the numberator to a

double, meaning that the compiler will treat it as adouble. If we didn't do that, we would end up with integer division, which is not what we want.

Slide 23

Overloading the << operator

- In C++, we can make our function utilize standard operators for their own purposes. For example, we could make the less than operator for our class compare our two fractions (see the demo code for an example of the less than operator).

- Because we might want to print out our fraction in fractional form (instead of decimal form), we can overload the

<<operator so we can use our class with<<:// purpose: To overload the << operator // for use with cout // arguments: a reference to an outstream and the // fraction we are using // return value: a reference to the outstream ostream& operator<<(ostream& out, Fraction& frac) { out << frac.num << "/" << frac.denom; return out; } - Example:

Fraction frac(4, 5); cout << frac << endl;Output:

4 / 5