Dynamic Memory

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2023, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Neel Kishnani

Slide 2

Announcements

- Midterm tonight!

- A4 will be out tomorrow.

Slide 3

Today's Goals:

- Introduce dynamic memory allocation

- Investigate arrays

- Discuss how data is laid out in memory

- Talk about the class destructor function

Slide 4

Dynamic Memory Allocation

- So far in this class, all variables we have seen have been local variables that we have defined inside functions. Sometimes, we have had to pass in object references to functions that modify those objects. For instance, take a look at the following code:

void squares(Vector<int>& vec, int numSquares) { for (int i = 0; i < numSquares; i++) { vec.add(i * i); } } - This function requires the calling function to create a vector to use inside the function. This isn't necessarily bad, but could we do it a different way? In other words, could we create the Vector inside the function and just pass it back, like this?

Vector<int> squares(int numSquares) { Vector<int> vec; for (int i = 0; i < numSquares; i++) { vec.add(i * i); } return vec; } - This works. There is one issue, though: you have to make a copy of the Vector, which is inefficient (though…these days if the creator of the Vector class is clever, we won't have to make a copy). Remember, we would rather not pass around large objects.

- Okay…maybe we can do this, instead?

Vector<int>& squares(int numSquares) { Vector<int> vec; for (int i = 0; i < numSquares; i++) { vec.add(i * i); } return vec; } - Does this work?

- No :( This is actually really bad. Why? The scope of

vecis only the function, and you are not allowed to pass back a reference to a variable that goes out of scope.

- No :( This is actually really bad. Why? The scope of

Slide 5

Dynamic Memory Allocation: Motivation

- What do we want here? What's the big deal?

- What we really want is really two things:

- a way to reserve a section of memory so that it remains available to us throughout our entire program, or until we want to destroy it (give it back to the operating system)

- a way to reserve any amount of memory we want at the time we need it.

- You might think that global variables are what we want, but that would be incorrect.

- Global variables can be accessed by any function in our program, and that isn't what we want. We want to control which function has access to the data, just like we normally would when passing data between functions.

- Global variables have a fixed size at compile time, and that isn't what we want, either.

Slide 6

Dynamic Memory Allocation: the new keyword

- C++ allows you to request memory from the operating system using the keyword

new. This memory comes from the heap whereas variables you simply declare come from the stack. Both of those terms will become important in CS 107, but for now, you need to know this:- Variables on the stack have a scope based on the function they are declared in.

- Memory from the heap is allocated to your program from the time you request the memory until the time you tell the operating system you no longer need it, or until your program ends.

- To request memory from the heap, we use the following syntax:

type* variable = new type; // allocate one elementor

type* variable = new type[n]; // allocate n elements - This syntax is weird – what's with the asterisk (

*)?- The asterisk represents a pointer to a type, and we will formally introduce pointers next time. For now, we'll concentrate on using

newand we will see how pointers work soon.

- The asterisk represents a pointer to a type, and we will formally introduce pointers next time. For now, we'll concentrate on using

- Examples:

int* anInteger = new int; // create one integer on the heap int* tenInts = new int[10]; // create 10 integers on the heap - The second example (

tenInts) above is very powerful – the memory you are given is an array guaranteed by the operating system to be contiguous. So, that's how we allocate an array of items dynamically!

Slide 7

Arrays -vs- Vectors

- We have been using Vectors in class so far, and we've said "Oh, a Vector is just built on top of an array" but we haven't really discussed what an array is. Arrays are lower level than Vectors, and they are more limited. They do have similar syntax, though. Here is an example:

int firstTen[10]; // create a static array on the stack; // only available for this function int* secondTen = new int[10]; // create 10 integers on the heap // Dynamically allocated and available // for the rest of the program (if we wish) // fill memory with values for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { firstTen[i] = i * 2; // evens secondTen[i] = i * 2 + 1; // odds } - What we have above is a variable called

firstTen, which is an array of ten values, only available for our current function. We also have a variable calledsecondTen, which uses new to provide us ten values, and those values could be available for the rest of the program, if we wish. firstTenis an array, andsecondTenacts like an array – the distinction isn't critical right now (but will be critical in CS 107)- Notice that we access the elements of an array just like we access them in a Vector, with square brackets.

- Arrays are not objects – they don't have any functions associated with them. So, you can't do this:

int len = firstTen.length(); // ERROR! No functions! firstTen.add(42); // ERROR! No functions! firstTen[10] = 42; // ERROR! Buffer overflow!

Slide 8

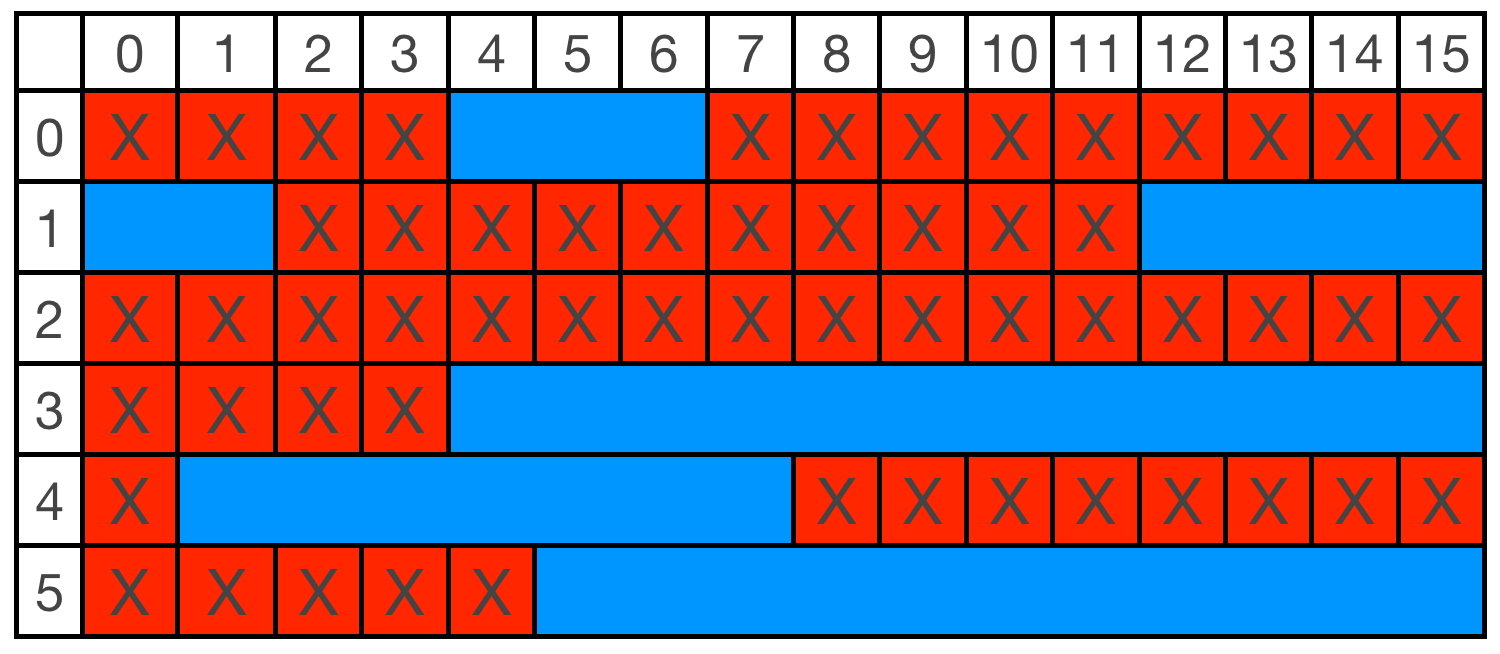

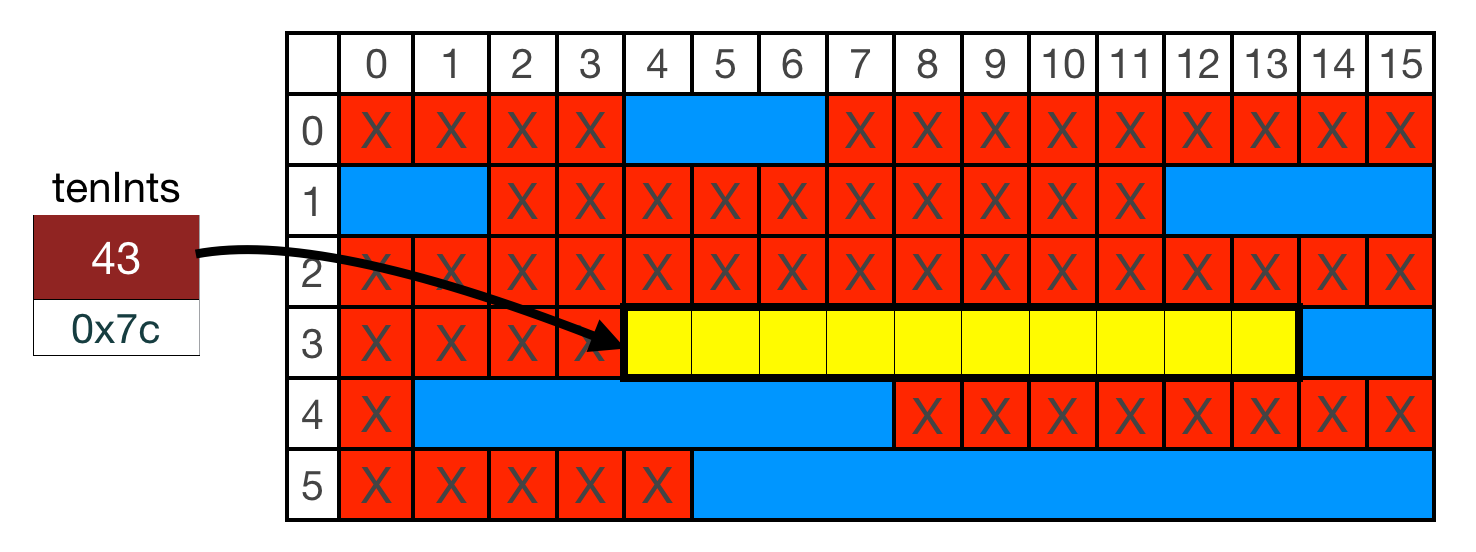

Dynamic Memory Allocation: under the hood

- The following statement requests an array of ten integers from the operating system (OS), on the heap:

int* tenInts = new int[10];The OS looks for enough unallocated memory on the heap in a row to give you, then returns a pointer to that location (red with X's is used, blue is free):

- For the above statement, the OS might pick row 3, column 4 for your request.

- Beware, that even though there might be free space after your request, you aren't allowed to use it:

- What would happen if you do try to write a value into a location you don't own?

- Possibilities:

- Compiler won't let you.

- Crash (seg fault)

- Nothing, as no one else is using that area

- Headline news for you in the New York Times.

- Compiler won't let you

- Sadly, the compiler won't tell you about this – you're on you're own!

- Crash (seg fault)

- Maybe, maybe not! You never know, and it isn't guaranteed

- Nothing, as no else is using that area

- Again, maybe? You don't know.

- Headline news for you in the New York Times.

- ???

- Possibilities:

Slide 9

Buffer Overflow

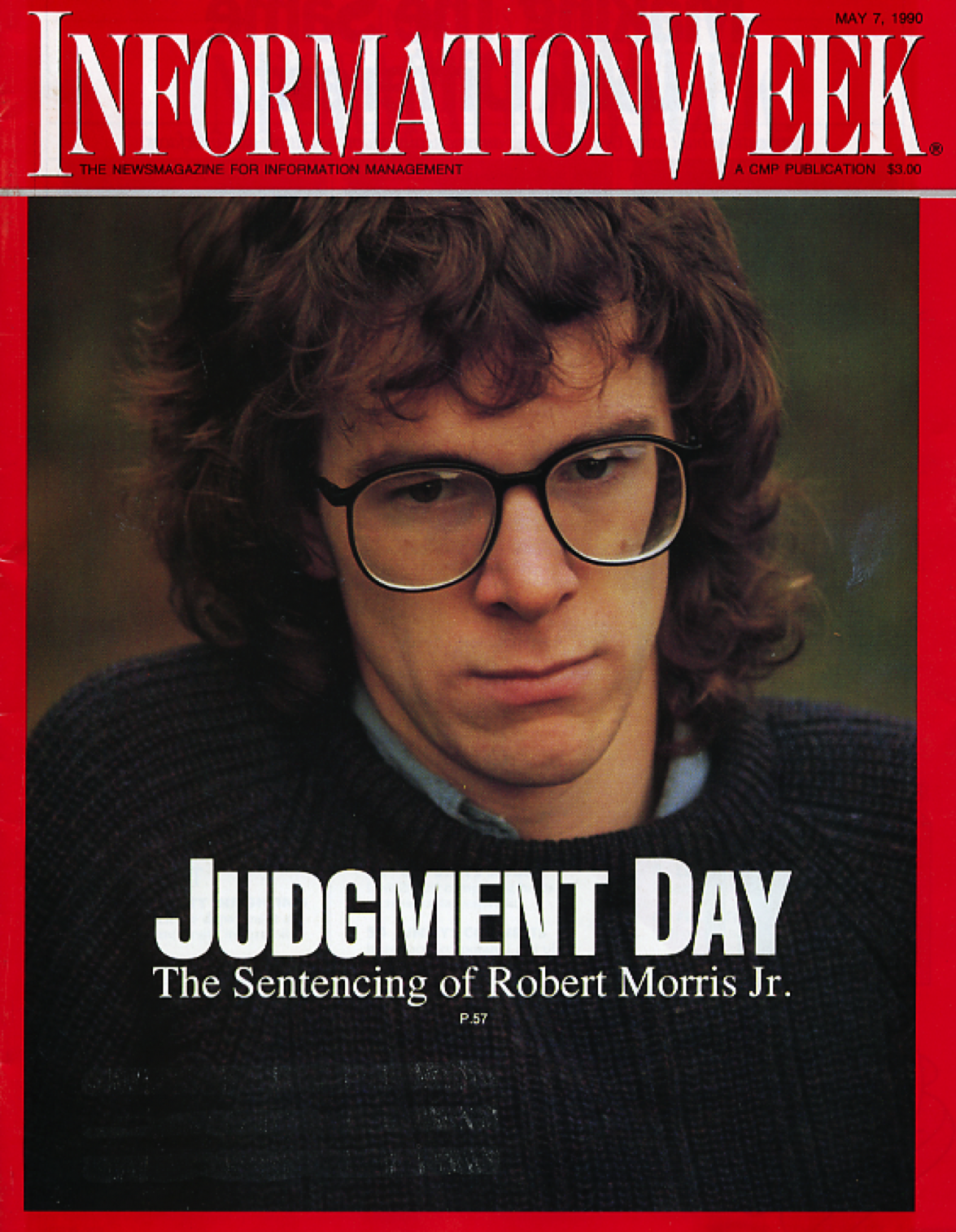

- In 1988, a computer "worm" written by Cornell graduate student Robert Morris, Jr. proliferated through government and university computers, bringing down the nascent Internet.

- The worm took advantage of a buffer overflow in a program, by writing code into a location that was outside the area that the program was given.

- The worm tricked the program into running its code, and was able to work its way through the network to other computers.

- The worm had a bug that made it eat up all of the computer's memory, thereby crashing the systems, one by one.

- Robert Morris, Jr. became the first person in the U.S. convicted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, and was fined, performed community service and served a three-year probation.

- He claimed that he was trying to demonstrate computer security faults, but the court did not believe him.

- He did bounce back: now he is a professor of computer science at MIT, and he co-founded the start-up incubator, Y-Combinator.

Slide 10

Dynamic Memory Allocation: delete

- When you dynamically allocate memory, the memory you request is yours until the end of the program, if you need it that long.

- You can pass around the pointer you get back as much as you'd like, and you have access to that memory through that pointer in any function you pass the pointer to.

- But, what if you are done using that memory? Let's say you create an array of 10 ints, use them for some task, and then are done with the memory?

- In this case, you tell the Operating System that you no longer need the memory, giving it back to the Operating System. To do that, you use the

deletekeyword:Fraction* myDynamicFraction = new Fraction; // create one Fraction on the heap int* tenInts = new int[10]; // create 10 integers on the heap for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { tenInts[i] = randomInteger(1, 1000); } someFunction(myDynamicFraction); someFunction(tenInts); // done using myDynamicFraction delete myDynamicFraction; // done using tenInts delete [] tenInts; // the [] is necessary when you have more than one value to give back deleteis a terrible, horribly named keyword. Let me repeat:deleteis a terrible name for what we are doing. It in no way deletes your memory, or the variable you're using, or anything. You think that's what it does, but it doesn't.- What it really does is to tell the operating system hey, I'm done with this memory – go ahead and give it to someone else if you want!

- That's it. No deleting anywhere. You should not try to access the memory again. But guess what? You can re-use the variable if you want! Remember, no deleting. The following is fine:

int sum = 0; int* blockOfInts = new int[5]; for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { blockOfInts[i] = 42; } for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { sum += blockOfInts[i]; } delete[] blockOfInts; // give the memory back blockOfInts = new int[100]; // this is okay! for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) { blockOfInts[i] = 142; } for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) { sum += blockOfInts[i]; } cout << sum << endl; delete[] blockOfInts; // not really deleting, giving back the memory!Output:

14410

- Without knowing it, you have been using dynamic memory all along, through the use of the standard and Stanford library classes. The string, Vector, Map, Set, Stack, Queue, etc., all use dynamic memory to give you the data structures we have used for all our programs.

Slide 11

The class destructor function

- When do we use

delete?- When we are done using the memory

- How do we know we are done using the memory?

- Well, that depends…in a class, we don't necessarily know when the user is going to be done with the class.

- Except…we know that if the class instance goes out of scope, it's no longer needed!

- In that case, when the class goes out of scope, we want to clean up our memory. We have a way of doing that, called the destructor. The destructor is automatically called when the class instance goes out of scope (or is itself deleted).

- You declare a destructor in the header file as follows:

~ClassName();If our

Fractionclass had used dynamic memory, we would have had:~Fraction(); -

Again, like constructors, there is no return value.

- Inside the destructor, we clean up everything we allocated dynamically:

// destructor Fraction::~Fraction() { delete[] myDynamicMemory; // ...etc }

Slide 12

Thought experiment: the scary world without dynamic memory

- What if (horror!) we took away the Stanford library and asked you to write a Microsoft Word clone. Maybe you would start with something like this:

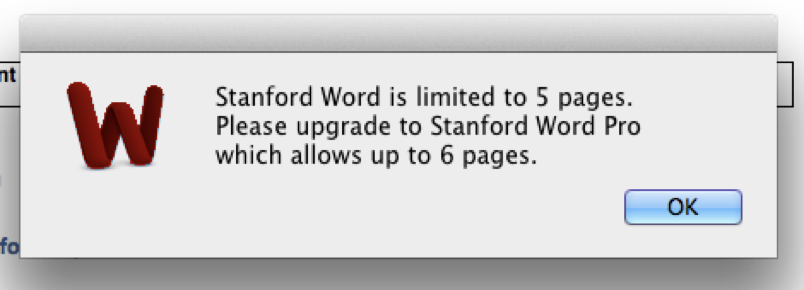

class Page { string text; double leftM, rightM, topM, bottomM; // margins string header, footer; int textColor; void printPage(); }; - How many pages should we allow the user of Stanford Word? 5?

int main() { Page pages[5]; // array of 5 pages } - People probably wouldn't buy your program if you limited them to five pages.

- Okay, let's make it bigger. How big? 6 pages? 100 pages? 1,000,000 pages?

- This is a no-win battle.

- Too small, and your user might be unhappy.

- Too big? Waste of memory! Your program would hog memory if you did the following:

int main() { Page pages[1000000]; // array of a million pages }

- Soon, we will discuss how to use dynamic memory to avoid this conundrum. Stay tuned!