View Types

The True Perspective View

The Dilated or “Open Book” View

The Telescoped or “Collapsed Space” View

The Composite or Collage View

The Capriccio View

The Embedded View

The Bird’s Eye View (Elevated View)

Lighting Effects

The True Perspective View

Plate 27, Piazza S. Pietro, and corresponding photograph

The True Perspective View constitutes about one quarter of all the plates in the Magnificenze. This view captures a scene accurately according to the tenets of mathematically based perspective or the exactness of the photographic lens. Objects and space are shown accurately and the disposition between them is rendered correctly according to real space. This technique was reserved for sites where there was sufficient space between the observer and the subject and there were no structures to obstruct the view. The view of Piazza S. Pietro, Plate 27, is a good example. This view type is important to note for it proves that Vasi had ample skills to render all his scenes with scientific accuracy had he chosen to do so. The fact that he employed this straightforward approach with a certain reserve indicates his willingness, indeed the necessity, to take liberties with his compositions in order to make them more comprehensible than a mechanically constructed perspective would allow.

The Dilated or “Open Book” View

Plate 69, Palazzo Borghese, and corresponding photograph

The Dilated View type affects space more than surrounding structures. Typically Vasi will widen a narrow street or expand a piazza (even if somewhat broad to begin with) to reveal the bounding sides of the space. The distortion, then, focuses on the space between structures leaving the buildings, fountains, and other features relatively or completely unaffected. This type of distortion is the most common of Vasi’s methods and stems from that same technique used by other vedutisti such as Falda and Cruyl. An almost exactly analogous case to Vasi’s Dilated View of Palazzo Borghese, Plate 69 is that of Falda’s view of the same palace using virtually the same station point. Both Vasi’s and Falda’s plates show the palace with its piazza widened toward the river in order to display a view of Prati and S. Peter’s in the distance, a prospect that does not actually exist from this vantage point but one that was nonetheless important to the idea of the palace and evokes its strategic location on the banks of the Tiber which did afford such as view.

The Telescoped or “Collapsed Space” View

Plate 172, Spedale di S. Giovanni in Laterano, and corresponding photograph

The Telescoping View collapses space so that distant objects appear much closer than in reality. This technique allows for closer inspection of distant objects and facilitates informative juxtapositions even while defying the scientific logic of the scene. In the Spedale di S. Giovanni in Laterano, Plate 172, Vasi shows the men’s and women’s hospital of S. John’s in the Lateran in the foreground. This in turn frames the distant Coliseum which looms much larger than life in the print. The scene makes clear that the Cathedral of Rome was directly linked to the ancient place of Christian martyrs further reinforced by the fact that it is along this street, Via S. Giovanni in Laterano, that the Papal procession, Il Possesso, took place during the ceremonies inducting a new Pope.

The Composite or Collage View

Plate 113, Piazza S. Eustachio (Vasi’s print and composite photograph)

Vasi’s method was not tied down to a single fixed station point as is the case with the eye of the camera or scientific perspective. Any given scene by Vasi is typically a composite view taken from multiple station points resulting in a kind of ‘collage’ that combines aspects of a site to their best advantage unifying them into a single scene that is at odds with physical and spatial reality but is nonetheless visually convincing. A good example of this practice is Piazza S. Eustachio, Plate 113). The technique is discussed by David Hockney in Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (2001). Although resembling a panorama, The Composite or Collage View is not a true panorama as it requires a single station point around which the viewer pivots. This technique is quite common in the Magnificenze (at least two thirds of all views fall into this category). Particularly vivid examples include Piazza S Eustachio, Plate 113, Piazza del Popolo, Plate 21A, and Chiesa di S. Giorgio in Velabro, Plate 55.

The Capriccio View

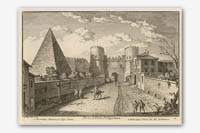

Plate 63, Palazzo Colonna, Plate 193A Giardino Colonna

The Capriccio View type transforms a scene by moving or deleting objects to allow for unobstructed viewing or to better frame or enhance the primary view. The Capriccio View is rarely employed by Vasi. Capriccio (Italian meaning fantastic or whimsical) is a term used to define an artistic genre that deliberately constructed imaginary scenes by combining two or more known buildings and site features into a scene. Vasi’s predecessor Giovanni Paolo Panini mined the aesthetic potential of this visual slight of hand. It is also invoked in modern urban theory as a legitimate means for critiquing urban ensembles and creating new ones. Vasi’s Capriccio Views are not true capricci as he does not literally move buildings from remote sites with the intention of creating new urban ensembles. His intention is more modest and practical: it provides a means to better reveal an actual site, removing building that would obscure a view and sometimes moving relatively minor props, like obelisks or fountains or ruins to act as a reminder of some noteworthy attribute associated with the site that would otherwise be invisible. For example he shows the Colonna family’s ancient ruins as if they were placed in front of the palace whereas they are actually located in the rear garden, Plates 63, 193A.

The Embedded View

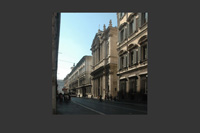

Plate 44, S. Maria in Via Lata, Corresponding Photograph

The Embedded View assumes an impossible station point embedded in an opposing building fabric for better viewing. Akin to the Capriccio View, the Embedded View type removes structures but does not add new ones. Vasi’s print of S. Maria in Via Lata, Plate 44, reveals an almost frontal, one point perspective view of the church and adjacent Palazzo Panfili, an impossibility in reality because of the limited width of Via del Corso . In this case the imagined station point would be located inside nearby S. Marcello.

The Bird’s Eye View (Elevated View)

Plate 196, Villa Mattei

The Bird’s Eye or Elevated View is, strictly speaking, not a distortion at all. In this type of view the station point was taken from an imagined aerial position. The tradition of elevated views has a well established pedigree in Roman vedute referred discussed elsewhere which sometimes bridges the gap between cartographic and veduta representations. Vasi’s predecessors used the technique extensively, especially Falda who in his1676 plan of the city capitalizes on this method although his depiction strictly speaking is an example of a paraline drawing and not a true perspective view at all. Many of Falda’s other views, particularly those of the villas of Rome, use a bird’s eye perspective and it is here that Vasi probably gleaned the most from this late 17th century master. Sometimes the elevated station points are not provided by actual structures. These are rare in Vasi’s views (Castro Petorio, Plate 5A, is one such exception). Typically elevated station points can be traced to the piano nobile level (first floor) of surrounding buildings, such as the view of Piazza Navona, Plate 26, which is taken from the first floor window, just to the left of the central window, of Palazzo Lancellotti which is located in the southeastern corner of the piazza.

Lighting Effects

|

|

|

Morning |

Late Afternoon |

Night |

Vasi’s remarkable attention to detail comes to the fore especially when one examines the quality of lighting in his views and the exacting representation of shade and shadows. There is, for example, always a defined light source which can be clearly interpolated by cast shadows and highlighted clouds which lend a naturalistic aspect to his work. At times dramatic sunrises or sunsets add a note of the sublime, as seen in Porta Angelica, Plate 19 (sunset) and Porta Maggiore, Plate 11 (sunrise). Some views capture the mood of a critical “moment” such as his print of Piazza S. Pietro, Plate 27, which shows carriages in early evening light leaving the basilica after vespers. The festival celebration "refrigerio" in the Piazza Navona, Plate 26, is shown at mid-day in August. The luminescent quality of the prints is reinforced by the depiction of other atmospheric and natural conditions. For example there is not one cloudless sky in all 238 plates of the Magnificenze the only exception being one night view of the Porta Settimiana, Plate 14 where the stars shine and the moon casts a pale shadow. The time of year in which Vasi drew his scenes can be deduced for nearly every plate. This is most easily seen in north-facing structures which are in deep shade for much of the year. The Pantheon, Plate 25, and the Porta del Popolo, Plate 1, are examples where he depicts early morning lighting effects for each during the summer solstice. Similarly, Vasi shows a late afternoon view of the Porta Angelica, Plate 19, also taken on or near June 21. |