Maintenance

Maintenance: Production

I.

IntroductionII.

Raw Materials- Plants

- Animals

III.

Technology- Farming Tools

- Maintenance of Soil

- Prevention of Erosion

- Irrigation

- Terracing

IV.

Maximization and Distribution- Verticality

- Transportation

Back to Maintenance Front Page

Previous Page: Administration | Next Page : Storage

I. Introduction

The Incan Empire encompassed a wide variety of landscapes from coastal deserts to tropical forests and from mountain terrain to wet punas (windy plateaus). The Incasí ability to thrive in areas poorly suited for agricultural production is perhaps their most impressive feature. They were able to do so both by taking advantage of given resources and by maximizing them through the use of technology.

Top of Page

II. Raw Materials

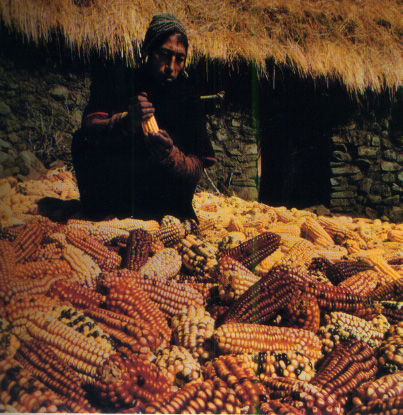

A. Plants

The farmers of each region grew crops suited to their area's altitude and climate. While farmers in warm and coastal areas could easily cultivate maize, beans, and squash, farmers in the mountain regions face problems like shorter growing seasons, low temperature as well as arid conditions. The tuber family of plants adapted especially well to high altitudes up to 1300ft above sea levels on the Andean slopes. Thus crops like the potatoes were cultivated as early as 6000 BC. In time, the farmers also crossed and selected different strains of tubers that were more able to resist frost as well as gather nutrients from the highly used fields.

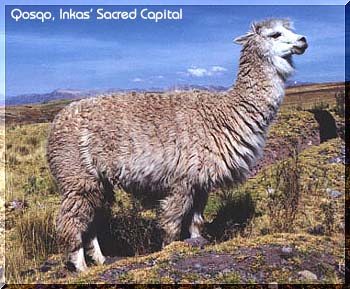

B. Animals

Although the South American continent lacked the variety of land mammals available to early European agrarian settlements, the Incas made heavy domesticated use of the cameloids endemic to the mountainous Andes. Alpacas and llamas served as pack animals for transportation and were important sources of wool, meat, and milk. Salted cameloid meat was also an important food source that the Incas would put in storage (link) for long periods of time up to four years!

Top of PageIII. Technology

A. Farming Tools

Due to the lack of large domesticated animals available to Incan farmers, the preparation of the farmland was mostly human labor intensive. Chakitaqllas were foot-plows that allowed farmers to aerate the soil before planting crops. These important agricultural tools were simple wooden sticks with heads made of metal or a harder wood.

B. Maintenance of soil

In order to compensate for the lack of native fertile soil on the Peruvian highlands, the Incans introduced natural fertilizers in order to maintain a nutrient rich field without the use of fallow crop rotation. These fertilizers included cameloid manure, island birdsí manure (guano), or some other form of nitrogen rich organic material.

C. Prevention of Erosion

Inorganic sediment and metals present in ice-core drillings from pre-Inca societies between 2000 BC to 100 AD suggest that erosion and runoff were persistent problems during this era. The Incas planted trees, especially the nitrogen-fixing alder tree Alnus amcuminata, to prevent erosion, while also gaining a source of building material and fuel. Terracing was another means of minimizing erosion and also enabled farmers to maximize production on the steep slopes of the Andes.

Irrigation canal

D. Irrigation

The Incas constructed magnificent irrigation system that supplied water to farmers throughout the empire--from low deserts to terraced highlands. In fact, 85% of all the farmlands were sustained by canal irrigation, which supplemented seasonal precipitation. The sheer size and length of the canals required the coordinated efforts of the state in order to initiate and complete their construction. Yet once the water source was tapped, each canal could sustain a pocket of independent agricultural communities.

In addition to canals, farmers also increased their input of water by making "ridged fields" in which soil was mounded along the rows of plants to retain rainwater. They also used artificial ponds called cochas to collect and store rainfall. Overall, the irrigation system worked very closely with the terraces that carved the highlands of the Andes.

E. Terracing

Terraces are graduated pieces of farmlands that cover the slope of a mountain or a hill like steps. The terrace had three main parts: (1) solid foundation of large stones and a subsoil of clay, (2) retaining walls made of stone that separated each strata, and (3) a thick layer of topsoil (2-3 feet deep) brought from fertile valleys. Built on slight grade, channels of water can then run among the layers and provide each level with water from the irrigation source.

The purpose of the terrace is to maximize arable lands and prevent erosion and water loss. The complementation of terracing with the irrigation system had allowed the Inca to reclaim much of the slopes of the Andes for crop cultivation. In addition, terraces along the different altitudes created "microclimates" in which different species most suitable to each niche can flourish.

Top of PageIV. Maximization and Distribution

A. Verticality

As mentioned before, the Inca empire consisted of lands of dramatically different climates and geography. Verticality is an overarching concept of taking advantage of all the ecological niches and incorporating them into a system of production. The name verticality stems from the fact that much of the niches were created due to the difference in elevation. More concretely, vertically involves production in all areas varying in precipitation, temperature, and elevation. Although farmers of each region may specialize in cultivation within their respective ecological niche, they all contribute and pool their resources to supply a larger community. Verticality is made possible by communication and transportation through the use of roads and is another demonstration how the Inca empire was able to pool and distribute resources.

For diagram of Andean topography and climate see

AppendixB. Transportation

One of the greatest achievements of the Inca civilization was their extensive road system. The road network was a vast lattice of at least 23,000 kilometers. Ironically, the Incas did not have the technology of the wheel, and even though the roads were rough by European standards, the road system is considered one of the greatest achievements of native America. Even to this day, some of the roads are still intact and in good condition.

The roads served as the tie between all of the individual farmers and the dense population centers, where the state collected their taxes. They also linked different ecological regions that could develop complementary trade products. Moreover, the roads were an omnipresent symbol of the empire throughout the Andes. Nearly all of the millions of the subject peoples of the Incas had seen an Inca road. It was their tie to the authority of the sate, which managed its vital labor recruitment through installations on the roads.

Back to

Maintenance Front PagePrevious Page: Administration | Next Page : Storage