Exam Statistics

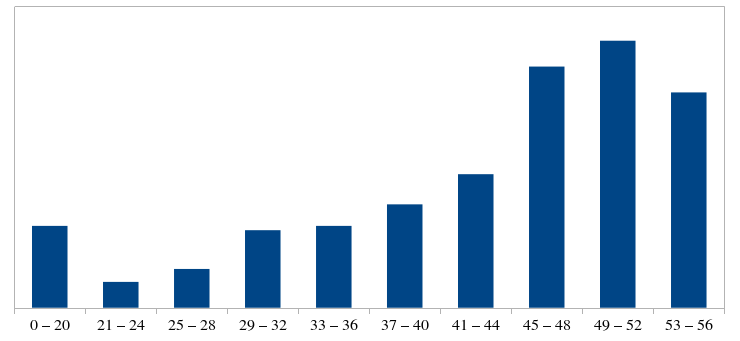

Here's a histogram of the scores on this exam:

To contextualize this, here are the quintile scores:

- 80th Percentile: 52 / 56 (93%)

- 60th Percentile: 48 / 56 (86%)

- 40th Percentile: 43 / 56 (77%)

- 20th Percentile: 35 / 56 (63%)

Exam scores, along with the graders' feedback, are available online on Gradescope. If you believe we made an error when grading your exam, you can submit a regrade request using this form until Thursday, March 23rd at 12:00 noon Pacific time.

Problem One: Repetitive Repetition (8 Points)

Below are four different implementations of a function

bool containsRepeats(const Vector<int>& elems);

that takes as input a Vector<int> and returns true if the Vector contains two or more copies of some integer and false otherwise. For example, containsRepeats({1, 2, 3, 4, 5}) would return false, as would containsRepeats({1, 0, 6}), but containsRepeats({3, 1, 4, 1, 5}) would return true (there’s two copies of 1), containsRepeats({9, 9, 9}) would return true (there’s three copies of 9), and containsRepeats({2, 7, 1, 8, 2, 8}) would return true (there’s two 2’s and two 8’s).

For each of these implementations, read over it to determine whether it works correctly on all inputs or whether it contains a bug. If it works correctly on all inputs, tell us its worst-case big-O runtime as a function of $n\text,$ the number of elements in the Vector. If it does not, give us an input where it behaves incorrectly. No justification is required.

-

bool containsRepeats(const Vector<int>& elems) { for (int i = 0; i < elems.size(); i++) { for (int j = i + 1; j < elems.size(); j++) { if (elems[i] == elems[j]) { return true; } } } return false; }This implementation is correct, and its worst-case runtime is $O(n^2)\text.$

Justification: This code works by forming all possible pairs of elements from the input list; index

\[(n-1) + (n-2) + \dots + 3 + 2 + 1 = O(n^2)\text.\]irepresents the first index of the pair, and indexjrepresents the second. The work done is $O(n^2)$ because the inner loop first runs $n - 1$ times, then $n - 2$ times, then $n - 3$ times, etc., for a total work of

-

bool containsRepeats(const Vector<int>& elems) { /* As a refresher, the Set type is implemented using a self- * balancing binary search tree. */ Set<int> used; for (int elem: elems) { used += elem; } return elems.size() != used.size(); }This implementation is correct, and its worst-case big-O runtime is $O(n \log n)\text.$

This works by using the fact that a set will automatically remove duplicates. Therefore, if there's a duplicate somewhere in the set, the set won't have the same size as the input vector.

Each insertion or deletion on a set takes time $O(\log n)$ when the set has $n$ elements, since that's the worst-case runtime of inserting an item into a self-balancing binary search tree. The total work is therefore $O(n \log n)$ in the worst case when all $n$ items are different.

-

bool containsRepeats(const Vector<int>& elems) { /* Map is internally implemented as a self-balancing binary * search tree. */ Map<int, int> freqMap; for (int i = 0; i < elems.size(); i++) { freqMap[elems[i]]++; } for (int i = 0; i < elems.size(); i++) { if (freqMap[elems[i]] > 1) { return true; } else { return false; } } }This implementation does not behave correctly on any input containing a duplicate whose first element is not repeated, or on an empty vector.

To see why this is, notice that the second

forloop can never execute more than once. After the first iteration, it will have either executed areturn trueorreturn false, which ends the function without looking at the other elements. So, if the first element isn't duplicated, the function will returnfalsewithout looking at any other elements.This function also fails on an empty vector. In that case, neither loop executes, and the function exits without returning a value, which is a Bad Thing. (Technically it's called undefined behavior and anything can happen - which in our book means "does not behave correctly.")

-

bool containsRepeats(const Vector<int>& elems) { if (elems.size() < 2) { return false; } HeapPQueue pq; // From A5 for (int elem: elems) { DataPoint data; data.name = ""; // Not used data.weight = elem; pq.enqueue(data); } DataPoint last = pq.dequeue(); while (!pq.isEmpty()) { DataPoint curr = pq.dequeue(); if (curr.weight == last.weight) { return true; } last = curr; } return false; }This implementation is correct, and its worst-case big-O runtime is $O(n \log n)\text.$

This works by loading the items into a priority queue and pulling them out one at a time. If there's a duplicate, at some point two identical items will be pulled out one after the other from the priority queue.

Because each enqueue and dequeue on a priority queue takes time $O(\log n)\text,$ this takes time $O(n \log n)$ overall.

Why we asked this question: This problem was designed to assess two separate skills. First - can you read a piece of code closely to understand both what it does and what it's trying to do? Second - can you evaluate the big-O time complexity of a piece of code, particularly when that code makes use of complex data structures?

To that first point (code reading), the first of these was designed to make sure you were comfortable with C++'s syntax for for loops and understood why one of the loops would be shifted relative to the other. The second of these pushed on the fact that the Set type doesn't allow for duplicates. The third hit on a very common bug from the quarter - returning from a for loop too early. The fourth was a more nuanced algorithm that relied on the fact that by sorting the elements of the input list, duplicate values would become adjacent.

To that second point (big-O notation), the first of these was intended to let you show us what you'd learned about analyzing nested loops. Whether you realized that both loops could run $O(n)$ times each, or whether you recognized the loop structure is the same as that for insertion or selection sort, our hope was that you'd conclude that the overall runtime was $O(n^2)\text.$ For the second, the main skill necessary is remembering that inserting into a self-balancing binary search tree takes time $O(\log n)$ in the worst case, so doing $n$ total insertions would take time $O(n \log n)\text.$ For the fourth, we intended to let you show us that, in working through the HeapPQueue assignment, you'd have internalized that the operations on a binary heap take time $O(\log n)$ each, so the overall runtime would be $O(n \log n)\text.$

Common mistakes: In part (i) of this problem, the most common mistakes involved getting tripped up by the loop indices. Many submissions incorrectly reported that the code would fail on an empty list (because we'd have j = 1), that the code would only check adjacent pairs in the list (because j = i + 1), or that the could would fail on every list (because when i = elems.size() - 1, we have j = elems.size()). All of these insights are based on real concerns about indices, but they turn out not to matter because in each case, the second loop won't execute because j < elems.size() will be false.

In part (ii) of this problem, the most common mistake was reporting the runtime as $O(n)$ rather than $O(n \log n)\text.$ We suspect that this is due either to forgetting to account for the cost of the BST operations, or by confusing BSTs with hash tables when working with the Set type. We also saw many answers that said the runtime is $O(\log n)\text.$ That's the cost of any one individual operation on a binary search tree, but since we're performing $n$ total operations on the BST, we have to scale that by the number of operations.

In part (iii) of this problem, the most common mistake was not realizing that the early return was a problem. We saw many solutions that reported the runtime was $O(n \log n)$ or $O(n)$ without noting the error. The mistake here is subtle but important, since, as you've seen when working with recursive functions, returning too early is a common way to have a very-close-but-not-quite-right piece of code. The other mistake we saw was identifying that the code didn't work, but not producing a specific input that causes the code to fail. Many submissions pointed out that the else return false should be outside the for loop, which is correct, but the problem statement specifically asked for an input that caused an incorrect answer. We asked this because we wanted folks to show not just that they knew that the code was wrong, but understood what, specifically, would happen when that code executed and why that code was wrong.

In part (iv) of this problem, the most common mistakes were reporting that the algorithm would behave incorrectly on certain inputs. A common class of inputs we saw were lists where there are duplicates that are not adjacent to one another in the input Vector. Those inputs are actually handled perfectly well by the algorithm: we're dequeuing elements in ascending order of value, so the positions of the elements in the original input are not meaningful. The other common mistakes we saw were giving runtimes of the form $O(n^2 \log^2 n)$ or $O((n \log n)^2)$ because there were two loops that each did $O(n \log n)$ work. Remember that you only multiply runtimes together if you're performing operation. $X$ a total of $Y$ times. Here, since we're doing the first operation, then the second, we add the runtimes.

Problem Two: We All Fall Down (12 Points)

Jetlag is a game that is played as follows. You are given a Grid<bool>, where each grid cell is either full (true) or empty (false). You’re also given a starting position within the grid. At each step, you can either move diagonally down-left or diagonally down-right one step. The goal is to reach the bottom of the grid without stepping on any full (true) cells and without stepping off the grid.

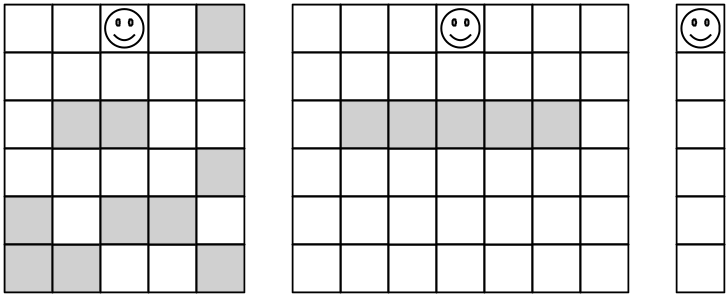

For example, here are three samples games of Jetlag:

In the game to the far left, there is only one way to win: move down-right, then down-right, then down-left, then down-right, then down-left. In the game in the middle, there is no way to win; try as you might, you can’t get around the barrier. In the game on the far right, there is no way to win; any step you take will immediately cause you to walk off the grid.

We can describe a solution to a Jetlag game as a string made of the characters 'L' (diagonally down left), or 'R' (diagonally down right). For example, the leftmost game has solution "RRLRL".

Write a recursive function

Optional<string> solveJetlag(const Grid<bool>& world, int row, int col);

that returns a solution to the given Jetlag puzzle starting at the indicated position. If no solution exists, this function returns Nothing.

Some notes on this problem:

- Your solution must be recursive, though you’re welcome to make it a wrapper if you would like.

- As a refresher, you can check if an

Optionalcontains a value by comparing it againstNothing. If it contains a value, you can access that value by calling the.value()function.

Here's one solution that works by building up the result string as the function calls unwind. No wrapper is needed.

Optional<string> solveJetlag(const Grid<bool>& world, int row, int col) {

/* Base Case: If we're at an invalid location, there's no solution. */

if (!world.inBounds(row, col) || world[row][col]) return Nothing;

/* Base Case: If we're at the bottom row, we're done! */

if (row == world.numRows() - 1) return "";

/* Try moving down and to the left. If we can, great! We have a solution

* for the game we'd get if we were one row down and to the left. Adding

* an L to the front then gives the overall solution.

*/

Optional<string> left = solveJetlag(world, row + 1, col - 1);

if (left != Nothing) return "L" + left.value();

/* Same idea, but for the right. */

Optional<string> right = solveJetlag(world, row + 1, col + 1);

if (right != Nothing) return "R" + left.value();

/* Oh fiddlesticks; neither move works! */

return Nothing;

}

Here's one that uses a wrapper and explicitly passes down a partially-built solution.

Optional<string> solveJetlagRec(const Grid<bool>& world,

int row, int col,

const string& soFar) {

/* Base Case: If we're at an invalid location, there's no solution. */

if (!world.inBounds(row, col) || world[row][col]) return Nothing;

/* Base Case: If we're at the bottom row, we're done! */

if (row == world.numRows() - 1) return soFar;

/* Try moving down and to the left. If we can, great! We've got

* our solution.

*/

Optional<string> left = solveJetlagRec(world,

row + 1, col - 1,

soFar + "L");

if (left != Nothing) return left;

/* Otherwise, we must go right. If it works, great! Return the path found.

* If it fails, we'd get back Nothing, which we'd return anyway. Stated

* differently, if left doesn't work, we're 100% committed to going right.

*/

return solveJetlagRec(world, row + 1, col + 1, soFar + "R");

}

Optional<string> solveGetlag(const Grid<bool>& world, int row, int col) {

return solveJetlagRec(world, row, col, "");

}

Here's another solution route. This one removes the base case checks about being in-bounds and not being on a true cell and folds them into the recursion. This also requires us to add some extra checks to the wrapper to compensate. I'm personally not as much a fan of this solution because it duplicates the logic, but it's not wrong.

Optional<string> solveJetlagRec(const Grid<bool>& world,

int row, int col,

const string& soFar) {

/* Base Case: If we're at the bottom row, we're done! */

if (row == world.numRows() - 1) return soFar;

/* Try moving down and to the left. If we can, great! We've got

* our solution.

*/

if (world.inBounds(row + 1, col - 1) && !world[row + 1][col - 1]) {

Optional<string> left = solveJetlagRec(world,

row + 1, col - 1,

soFar + "L");

if (left != Nothing) return left;

}

/* Try moving down and to the right. If we can, great! We've got

* our solution.

*/

if (world.inBounds(row + 1, col + 1) && !world[row + 1][col + 1]) {

Optional<string> right = solveJetlagRec(world,

row + 1, col + 1,

soFar + "R");

if (right != Nothing) return right;

}

/* Oops, nothing works. */

return Nothing;

}

Optional<string> solveGetlag(const Grid<bool>& world, int row, int col) {

/* The original starting position might be invalid. */

if (!world.inBounds(row, col) || world[row][col]) {

return Nothing;

}

/* Otherwise we're at a valid spot, so see if we can take it from here. */

return solveJetlagRec(world, row, col, "");

}

Why we asked this question: We included this problem to let you show us what you'd learned about working with recursive backtracking and the Optional type, which you explored extensively in Assignment 4. We selected this problem specifically because we thought it was a good testbed for the major concepts in backtracking: exploring a set of options and stopping if any of them work correctly, keeping track of a partial solution or building one up as the recursion unwinds, etc. Also, we liked the use of Optional here, as that's something you worked with in two of the three problems from Assignment 4 and nicely encodes the idea of "either nothing or a string."

Common mistakes: Many of the mistakes on this problem are the sorts of common sticking points folks encounter when first learning recursion and recursive backtracking. Many solutions made the correct recursive calls, but forgot to capture the return values for later use. Others identified the correct base cases, but wrote them in the wrong order, causing invalid reads from a Grid (for example, checking if world[row][col] was true before seeing whether position (row, col) is inside the grid). Others still forgot to return Nothing in the event that both options at the given point did not work out.

We also saw many submissions that forgot to consider whether the starting position was valid. For example, what happens if the starting position isn't contained within the Grid, or is in the Grid but is at a true location? In both cases, you'd want to return Nothing because there is no solution.

We saw a number of folks with the right basic idea but who were having trouble with the Optional type. Many solutions tried comparing the .value() field on an Optional to Nothing rather than comparing the Optional itself against Nothing. Others tried &&ing together two Optionals, which would work if we were considering bools but which doesn't work with Optional<string>s.

Problem Three: Isn't Turing Great? (12 Points)

You work the front desk at Green Library. Whenever someone visits the library for the first time, you need to do some extra paperwork to help get them into the system. The question then comes up: given information about all past visitors to Green Library, how might you estimate the chance that the next person to visit is someone who has never visited before?

This turns out to be a well-studied problem, and there’s a very simple solution to it using something called a Good-Turing estimator. Here’s how it works:

- Maintain an array of

ints, all initially zero. - Whenever someone enters the library, hash their name and use it as an index into the array of

ints, then increment theintat that index. - To estimate the probability that the next person to visit is someone who hasn’t visited before, count how many of the

ints are equal to 1 and divide that by the number of ints that are greater than 0. (This might seem like a strange calculation to make, but surprisingly, it does a great job estimating the probability!)

Your task is to implement the following class:

class GoodTuringEstimator {

public:

GoodTuringEstimator(int numCounters);

~GoodTuringEstimator();

void personVisits(const string& name);

double estimateProbability() const;

private:

/* Up to you; see below */

};

Here’s the rundown on what these functions do. The constructor takes in a number of counters, then creates an array of that many counters, all initially 0. The destructor cleans up all memory used by the object. The personVisits function hashes the person’s name and increments the appropriate counter. The estimateProbability function returns the ratio of the number of counters equal to 1 to the number of counters that are greater than 0.

Your implementation, however, must comply with the following restrictions:

- You must do all your own memory management and must not use container types (e.g.

Vector,Set,Map,string, etc.) in the course of your solution. - The

personVisitsandestimateProbabilityfunctions must run in time O(1), regardless of how many counters there are. As a hint, add some extra variables to the class that track how many counters are equal to 1 and how many are greater than 0.

You’ll need to pick a hash function in the constructor. As a syntax refresher, you can call the function forSize(n) to get a hash function that produces hash codes between 0 and $n - 1\text,$ inclusive.

Some notes on this problem:

- You do not need to handle the case where the number of counters is zero or negative.

- You do not need to handle the case where

estimateProbabilityis called when all the integers are equal to zero. - Remember that by default, C++ will round down when dividing two integers.

Here's one solution that works by following the hint and storing the number of values equal to one and the number of values greater than zero.

class GoodTuringEstimator {

public:

GoodTuringEstimator(int numCounters);

~GoodTuringEstimator();

void personVisits(const string& name);

double estimateProbability() const;

private:

int* counters;

int numOnes;

int numNonzeros;

HashFunction<std::string> hashFn;

};

GoodTuringEstimator::GoodTuringEstimator(int numCounters) {

/* Initialize the array, setting each item to zero. */

counters = new int[numCounters];

for (int i = 0; i < numCounters; i++) {

counters[i] = 0;

}

/* Store a hash function for later. */

hashFn = forSize(numCounters);

/* Initially, everything is zero. */

numOnes = 0;

numNonzeros = 0;

}

GoodTuringEstimator::~GoodTuringEstimator() {

/* Cast off the counters array; we're done with it. */

delete[] counters;

}

void GoodTuringEstimator::personVisits(const string& name) {

/* Figure out which counter we want. */

int index = hashFn(name);

counters[index]++;

/* If the counter reads 1, then it went from 0 to 1 and both

* totals must be adjusted.

*/

if (counters[index] == 1) {

numOnes++;

numNonzeros++;

}

/* Otherwise, if it's 2, then there are fewer 1s than before. */

else if (counters[index] == 2) {

numOnes--;

}

}

double GoodTuringEstimator::estimateProbability() const {

/* Cast to double to make the division work properly. */

return double(numOnes) / double(numNonzeros);

}

Here's a different, similar solution that works by tracking the number of ones and the number of values greater than one separately.

class GoodTuringEstimator {

public:

GoodTuringEstimator(int numCounters);

~GoodTuringEstimator();

void personVisits(const string& name);

double estimateProbability() const;

private:

int* counters;

double numOnes = 0.0, numTwos = 0.0; // Use double so division is easier

HashFunction<std::string> hashFn;

};

GoodTuringEstimator::GoodTuringEstimator(int numCounters) {

/* Initialize the array, setting each item to zero. The use of

* parentheses after the 'new int[]' here initializes things to

* zero without needing a loop.

*/

counters = new int[numCounters]();

/* Store a hash function for later. */

hashFn = forSize(numCounters);

}

GoodTuringEstimator::~GoodTuringEstimator() {

/* Cast off the counters array; we're done with it. */

delete[] counters;

}

void GoodTuringEstimator::personVisits(const string& name) {

/* Figure out which counter we want. */

int index = hashFn(name);

/* If going from 0 to 1, increment 1s. */

if (counters[index] == 0) {

numOnes++;

}

/* If going from 1 to 2, increment 2s and decrement 1s. */

else if (counters[index] == 1) {

numOnes--;

numTwos++;

}

/* Increment the counter. */

counters[index]++;

}

double GoodTuringEstimator::estimateProbability() const {

/* To get the count of nonzero values, add up the number of counters

* exactly equal to one and the number of counters greater than one.

*/

return numOnes / (numOnes + numTwos);

}

Why we asked this question: This question was designed to let you show us what you've learned about building classes that work with dynamic arrays. If you squint at it the right way, this kinda sorta ish looks like what a hash table does: we have an array of slots (here, ints), a hash function mapping items to slots, and need to do some maintenance of internal state whenever we see an item come in.

We also chose this problem because, like what you saw on A7 when building the particle system, you need to do a bit of extra bookkeeping to hit all the necessary time bounds. In particular, you have to track the frequency of items equal to 1 and items greater than 0, which isn't too difficult in principle but which requires a bit of attention to detail.

Finally, we picked this problem because we thought it was a good venue for you to illustrate your understanding of some of C++'s finer points - things like how arrays of ints don't get automatically initialized 0 and how to divide two integers without immediately rounding down.

For those of you who are curious to learn more, the Good-Turing estimator works a little bit differently than what we asked you to do here. In a "proper" Good-Turing estimator, you would track the exact frequencies of each item seen, rather than just hashing to an array of counters, and would compute the fraction of items that have been seen exactly once divided by the total number of distinct items seen.

Common mistakes: The most common mistake on this problem was forgetting to initialize the array of counters to all be zero. As you saw in class and in the assignments, in C++ primitive types (pointers, ints, etc.) initially take on garbage values when created. As a result, you need to tell C++ to set all the counters to 0 when setting things up.

We also saw similar mistakes with storing information long-term, such as properly creating values but storing them as local variables in the constructor rather than adding them to the private section of the class. Also, many submissions forgot to store the hash function as a field of the class, which is necessary because the same hash function needs to be used each time an item comes in.

The actual logic to determine how many 1s there are and how many nonzero values there are are a bit more subtle than they might initially seem, as you can see from the above solutions. Many submissions forgot to handle the fact that counting how many 1s there are requires decrementing the total whenever a counter is bumped from 1 to 2.

Finally, we saw a number of solutions that attempted to divide two ints without rounding down, but which did so incorrectly. For example, the following does not work:

// Warning - incorrect code!

double result = numerator / denominator;

return result;

This code looks right, but it still does integer division. What will happen here is that numerator / denominator will be computed using integer division because numerator and denominator are both ints, and the resulting, rounded-down int will then be stored as a double. The fix is to ensure that at least one of the two numbers being divided is indeed a double, either by casting or by, say, adding 0.0 or multiplying by 1.0.

Problem Four: Twiddle (12 Points)

In this problem, we’ll be making use of the Cell type shown below:

struct Cell {

int value;

Cell* next;

Cell* prev;

};

This represents a cell in a doubly-linked list of integers.

Write a function

void twiddle(Cell* cell);

that takes as input a pointer to a cell in the linked list. Your function should then rewire the list to swap the order of that cell and the cell immediately after it. We specifically want you to rewire pointers while leaving value fields unmodified.

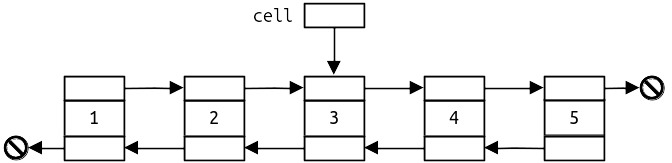

For example, suppose you’re given this input list, with cell as marked:

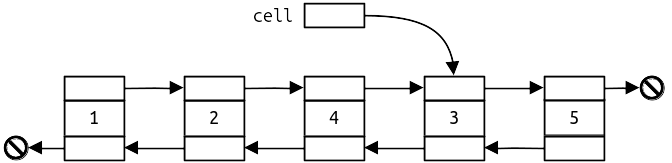

The resulting list should look like this:

Although it appears that the numbers in the cells have been changed, those numbers are unmodified. Rather, we’ve just updated some pointers so that the cells appear to be in a different order. We advise taking a minute to review the diagrams and determine which pointers have changed.

If the cell parameter is nullptr or is at the end of the list, your function should call error.

Some notes on this problem:

- You may not use any container types (

Vector,Map,string, etc.) in the course of this problem. - Do not allocate any new cells or modify the value field of any cells; instead, just rewire the existing cells in the list.

- There may be any number of cells in the list, and you may be given a pointer to any one of them.

Here's one possible way to do this.

void twiddle(Cell* cell) {

/* Validate inputs. */

if (cell == nullptr || cell->next == nullptr) {

error("You have committed a programming sin. :-)");

}

/* For simplicity, refer to the two cells to swap as 'one' (the first)

* and 'two' (the second).

*/

Cell* one = cell;

Cell* two = cell->next;

/* Also track which cells precede and follow the two cells in the list. */

Cell* before = one->prev;

Cell* after = two->next;

/* Set up links between 'before' and 'two', which now link together. */

if (before != nullptr) before->next = two;

two->prev = before;

/* Now link up 'one' and 'after'. */

if (after != nullptr) after->prev = one;

one->next = after;

/* Finally, reorder 'one' and 'two'. */

one->prev = two;

two->next = one;

}

Why we asked this question: The most common uses of linked lists in practice are scenarios in which a list of items must be stored while items are inserted, deleted, or rearranged. You saw one of those applications in Assignment 7, where you had to dynamically add and remove particles from a list quickly. This problem was designed to hit at the essence of those ideas by distilling everything down to a seemingly simple task: swap the order of two adjacent cells in a doubly-linked list. We figured this would be an excellent way for you to show us your understanding of linked list mechanics: tracking pointers to different cells, drawing out diagrams of what goes where, distinguishing between cells and pointers to those cells, etc.

To properly rewire things here, you need to change a total of (up to) six pointers. The two cells being twiddled need to update their next and prev pointers so that they locally swap positions and trade off which cells are before/after them (4 pointers). Then, the cell just before the two and just after the two, if any, need to have their next and prev pointers, respectively, rewired to reflect the new ordering. Throughout this process, you have to make sure that you don't lose track of any of the cells in the list by breaking the last remaining pointer to that cell.

Common mistakes: The most common mistake we saw on this problem was forgetting to account for the case where the two cells being twiddled either don't have anything after them or don't have anything before them. Many solutions included code like cell->prev->next = cell->next; or cell->next->next->prev = cell; that correctly rewire pointers if the relevant cells exist, but which are predicated on the assumption that cell->prev or cell->next->next are not nullptr. Accounting for those cases doesn't require much extra work, but you have to be careful to ensure that you indeed handle them.

Another common class of mistakes was incorrectly creating new cells with new Cell or deallocating cells with delete ptr. It's understandable why folks included this code in their solution, since it seems like new Cell would be needed to create a variable of type Cell*, and delete ptr seems like it would be needed to get rid of a pointer variable. However, remember that these statements actually do something very different - the first creates an entirely new linked list cell, and the second destroys an existing linked list cell. In other words, those are operations on cells, not pointers, and in our case we don't want to create or destroy any cells.

We also saw a number of submissions that forgot about one or two of the needed pointer changes. Some submissions beautifully rewired the next and prev pointers of the two cells to be twiddled but forgot about the cells before or after them. Others handled those pointers plus the pointers from the preceding cell, but forgot the cell after the two, or vice-versa.

Some solutions forgot to call error when the inputs were invalid, or called error in circumstances that weren't errors (for example, when cell was the first cell in the list).

A number of solutions tried using recursion or loops to solve the problem. In this problem, no searching of the list is necessary, since we're given a pointer directly to the cell we want to twiddle.

Finally, we saw some submissions that "lost" a cell. By that, we mean that those implementations assigned cell->next a new value, then tried referencing cell->next as if it still referred to the cell that used to follow cell at the start of the implementation.

Problem Five: Haircuts (12 points)

Suppose we have the following Node type:

struct Node {

int value;

Node* left;

Node* right;

};

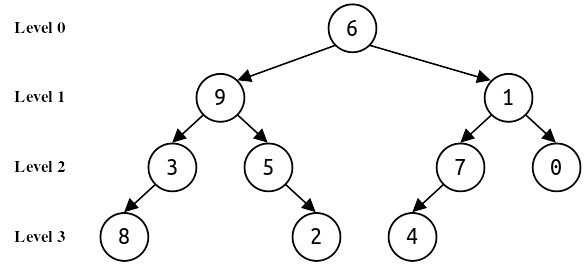

Given a binary tree (not necessarily a binary search tree, and not necessarily a binary heap), we can number the levels of the tree from top to bottom. The root is in level 0, its children are in level 1, their children are in level 2, etc. An example is shown below:

Write a recursive function

Set<Node*> trimAbove(Node* root, int level);

that works as follows. This function deallocates all nodes above the level given by the level parameter. For example, calling trimAbove(root, 1) on the above tree will delete all nodes above layer 1 (that’s just the root node), calling trimAbove(root, 3) on the above tree will delete everything above layer 3 (nodes 6, 9, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 0), and calling trimAbove(root, 0) on the above tree won’t remove anything, because there are no nodes above layer 0.

In addition to deallocating nodes, calling trimAbove(root, level) returns a Set<Node*> containing pointers to all the nodes at level level of the tree. For example, if root points to the root of the tree shown above, then trimAbove(root, 3) would delete all nodes in the tree except for 8, 2, and 4, and would return a set containing pointers to those three nodes. Calling trimAbove(root, 2) would delete the nodes containing 6, 9, and 1 and return pointers to the nodes containing 3, 5, 7, and 0. Calling trimAbove(root, 137) would delete the entire tree and return an empty set.

Some notes on this problem:

- Aside from the

Set, you should not use any other container types (Vector,Map,Queue,string, etc.) in the course of solving this problem. - You must implement this function recursively. If you’d like, you can make it a wrapper function.

- The

Setyou return should not include any null pointers. - You should not allocate any new

Nodes in the course of solving this problem, but you may need to deallocate nodes. - You do not need to handle the case where

levelis negative. - Your code should work for all trees, not just the tree shown above.

Here are a few different solutions to this problem, each of which illustrates a different set of insights.

This first solution is based on the insight that if you remove the root of a tree, you form two new trees, each of whom can have their levels numbered by subtracting one from the levels relative to the main tree.

Set<Node*> trimAbove(Node* root, int level) {

/* Base Case: If the root is null, there's nothing to do. */

if (root == nullptr) return { };

/* Base Case: If level is 0, then the root node is the only node at

* level 0 in the tree.

*/

if (level == 0) return { root };

/* Recursive Case: Delete this node, and possibly trim below us too.

* To ensure we don't lose track of the children, store pointers to

* the children before deleting the root.

*/

Node* left = root->left;

Node* right = root->right;

delete root;

return trimAbove(left, level - 1) + trimAbove(right, level - 1);

}

This second solution uses a wrapper function and recursively counts down which level we're in until we hit the level in question.

/* Trims all nodes above targetLevel. currLevel denotes our current level in

* the tree.

*/

Set<Node*> trimRec(Node* root, int targetLevel, int currLevel) {

/* Base Case: If the root is null, there's nothing to do. */

if (root == nullptr) return { };

/* Base Case: If we hit the target level, then hand back the node. */

if (targetLevel == currLevel) return { root };

/* Recursive Case: Recursively process the left and right subtree. Having

* done so, clean up the current node.

*/

auto left = trimRec(node->left, targetLevel, currLevel + 1);

auto right = trimRec(node->right, targetLevel, currLevel + 1);

delete root;

return left + right;

}

Set<Node*> trimAbove(Node* root, int level) {

return trimRec(root, level, 0);

}

This third solution uses a totally different strategy. We begin with a set of all the nodes in layer 0 and repeatedly use the nodes in the current level to work out the nodes in the next level, recursively wiping one level at a time.

Set<Node*> trimRec(const Set<Node*>& currLayer, int layer) {

/* Base Case: Hit the bottom layer? Return what we have. */

if (layer == 0) {

return currLayer;

}

/* Recursive Case: This layer needs to be deleted, and we need to form

* the layer below us.

*/

Set<Node*> nextLayer;

for (Node* node: currLayer) {

/* Add the children, then clean up this node. */

if (node->left != nullptr) nextLayer += node->left;

if (node->right != nullptr) nextLayer += node->right;

delete node;

}

/* Recursively clean up below this point. */

return trimRec(nextLayer, layer - 1);

}

Set<Node*> trimAbove(Node* root, int layer) {

/* Edge case: If the root is null, there's nothing to do. */

if (root == nullptr) return { };

/* Otherwise, recursively wipe the top layer and the ones beneath

* it.

*/

return trimRec({ root });

}

Why we asked this question: We included this question for three reasons. First, we wanted you to show us what you'd learned about recursively walking over a tree, and this problem gave an opportunity for you to do just that. Second, we included this problem because it involves dynamic memory management for linked structures, something that wasn't exercised in the previous problem. Finally, we included this problem because it's an example of recursive enumeration (if you think about it, the problem involves finding all nodes with a certain property), something that we covered extensively earlier in the quarter but which didn't do as much with in the tail end of CS106B.

Common mistakes: Many of the errors we saw on this problem are essentially tricky bits when working with recursion. Many solutions make the proper recursive calls, but didn't store the results of those calls. Whether you're working with an explicit binary tree or an implicit recursion tree, remember that if a recursive function call returns a value, it's important to capture that value so that you can use it later on. Similarly, some solutions tried using a loop over the recursive calls, which doesn't work particularly well here because there are only two different recursive calls to be made and they're easier to encode as two separate calls.

A common but subtle issue we saw was making recursive calls like these:

// Careful - this is subtly wrong!

return trimAbove(left, level--) + trimAbove(right, level--);

The intent here is to make two recursive calls, one to the left and one to the right, each of which works on the level one level below us. However, remember that there is a big difference between writing level - 1 and writing level--. Writing level-- means "permanently change level by subtracting one from it." Writing level - 1 means "give me the number that is one less than level." If you pass in level-- into a recursive call, you're permanently changing level within the existing call, which will cause future uses of level within the function to be incorrect. Worse, the expression level-- actually evaluates to the old value of level before one was subtracted from it, so it passes the wrong value into the recursive call.

Other mistakes on this problem focused more on working on trees. Many solutions forgot to account for the case where root was nullptr, or did so too late in the function (say, after another base case that returned a set containing root or after reading the left and right fields of the node pointed at by root). Other solutions referenced root->left and root->right after executing delete root, which reads from a destroyed Node object.