Practice Midterm Exam

Portions of this handout by Eric Roberts and Patrick Young

This handout is intended to give you practice solving problems that are comparable in difficulty to those which will appear on the midterm examination. But first we have some logistics:

Exam is open book, open notes

The examination is open-book and you may make use of any handouts, course notes/slides, your programs or other notes you've taken in the class. For the exam, all notes must be printed out or hand written. You may not use any resources on your computer (or other devices such as a tablet) during the exam (unless you have an academic accommodation to use such devices during exams in which case please let the teaching staff know).

Taking the exam on a computer

You will be taking the exam on a computer using special software that we provide for the exam. The software we provide basically acts as a simple text editor where you can write your answers. Notably, while using our software to take the exam you will not be allowed to access the internet, nor any other applications on your computer (including Pycharm). While taking the exam, you should remain within the BlueBook application for the entire duration of the exam. Our software will let the course staff know if you scroll away from the BlueBook application at any point during the exam.

BlueBook

The software we use is called BlueBook. Please checkout our handout on BlueBook information to download the software and take this practice exam in BlueBook format. We highly recommend taking this practice exam in BlueBook so that you can get a sense of timing and the software before the midterm. You can find the practice exam in the BlueBook Information handout.

Coverage

The midterm exam covers the material presented in class through today (April 27th), which means that you are responsible for the Karel material plus the Python material covered up through (and including strings). Data files (which will be covered in class on Friday) are not covered on the exam.

General instructions

Answer each of the questions included in the exam. Make sure to include any work that you wish to be considered for partial credit (even it is not compilable code).

Each question is marked with the number of points assigned to that problem. The total number of points is 120. We intend for the number of points to be roughly comparable to the number of minutes you should spend on that problem.

In all questions, you may include functions or definitions that have been developed in the course, either by writing the import line for the appropriate library or by giving the name of the function and the handout or date of the slides in which that function appears.

Unless otherwise indicated as part of the instructions for a specific problem, comments will not be required on the exam. Uncommented code that gets the job done will be sufficient for full credit on the problem. On the other hand, comments may help you to get partial credit if they help us determine what you were trying to do.

Exam

Take the practice exam on BlueBook

Problem 1: Karel the Robot (20 points)

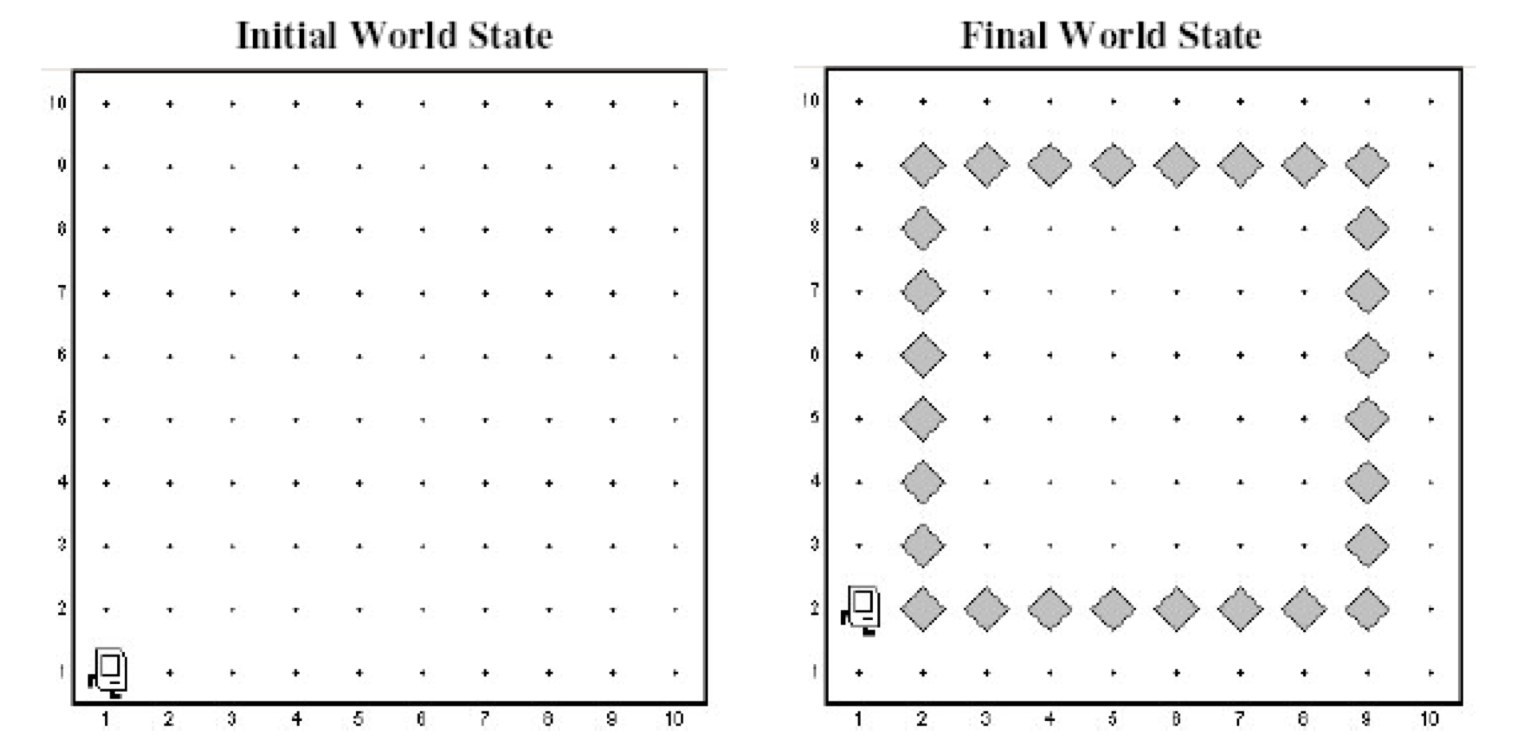

We want to write a Karel program which will create an inside border around the world. Each location that is part of the border should have one (and only one) beeper on it and the border should be inset by one square from the outer walls of the world like this:

In solving this problem, you can count on the following facts about the world:

-

You may assume that the world is at least 3x3 squares. The correct solution for a 3x3 square world is to place a single beeper in the center square.

-

Karel starts off facing East at the corner of 1st Street and 1st Avenue with an infinite number beepers in its beeper bag.

-

We do not care about Karel's final location or heading.

-

You do not need to worry about efficiency.

-

You are limited to the instructions in the Karel course reader. Notably you cannot use variables except as as the index variable in for loops (such as the variable i) and you cannot refer to that variable otherwise.

The starter code is below.

from karel.stanfordkarel import *

#

if __name__ == "__main__":

run_karel_program()

Problem 2: Full program (25 points)

For this problem, write a program that asks the user to enter integers until they enter a 0 as a sentinel to indicate the end of the input list. You program should then print out the largest and second-largest values from values the user entered. A sample run of the program might look like this (user input is in blue italics):

This program finds the two largest integers entered by the user. Enter values, one per line, using a 0 to signal the end of the input. Enter value: 7 Enter value: 42 Enter value: 18 Enter value: 9 Enter value: 35 Enter value: 0 The largest value is 42 The second largest is 35

To reduce the number of special cases, you may make the following assumptions:

-

The user must enter at least two values before the sentinel.

-

All values inputed by the user are positive integers.

-

If the largest value appears more than once, that value should be listed as both the largest and second-largest value, as shown in the following sample run:

This program finds the two largest integers entered by the user. Enter values, one per line, using a 0 to signal the end of the input. Enter value: 1 Enter value: 8 Enter value: 6 Enter value: 8 Enter value: 0 The largest value is 8 The second largest is 8

The starter code is provided below.

SENTINEL = 0 # the sentinel used to signal the end of the input

#

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Problem 3: Lists of lists (25 points)**

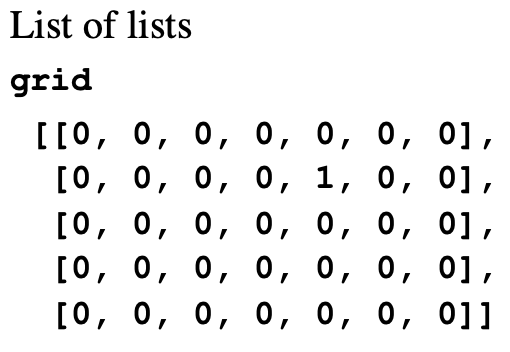

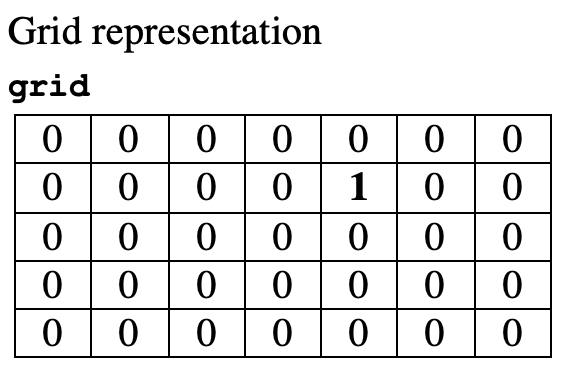

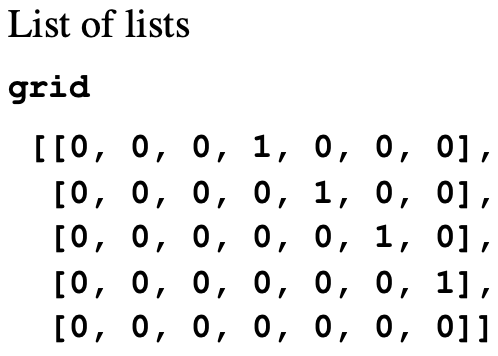

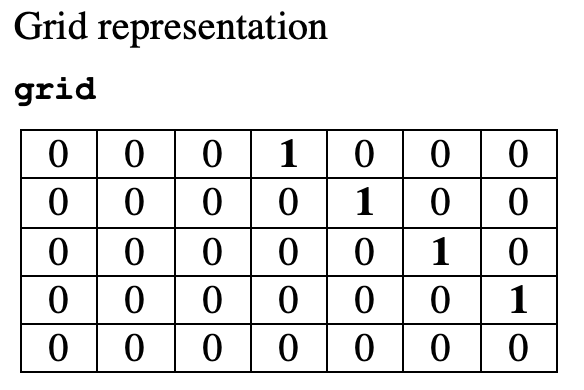

Say we have a 2-dimensional list (a list of lists) of integers, which we'll refer to as a variable named grid, that contains 0 in every element, except for one element, which contains a 1. Such a grid is shown below (first as a list of lists and then represented as a grid). Note the single 1 (which is bold-faced in the grid for clarity), which is in the second row, fifth column of the grid – that would be position grid[1][4].

We would like to create a diagonal line of 1's (going down and to the right) through the grid, which includes the initial 1 in the grid and extends to the edges (but, obviously does not go outside) of the grid. So, starting with the grid above, we would end up with the following final grid, showing both the list of lists and grid representations (again, the 1's in the grid are bold-faced for clarity):

The initial grid we are given can have any number of rows and columns (but it will be guaranteed to have at least one of each). You can assume that every element in the grid you are given, except for one, contains 0's and the remaining element has a 1. Your task in this problem is to write a function:

def diagonal_line(grid)

which is passed a 2-dimensional list representing the grid (as descibed above). When the function is done, the grid passed in should now contain a "diagonal" line of 1's that includes the 1 initially in the grid and all other elements in the grid should still be 0's. You do not need to write a complete program, just the diagonal_line function.

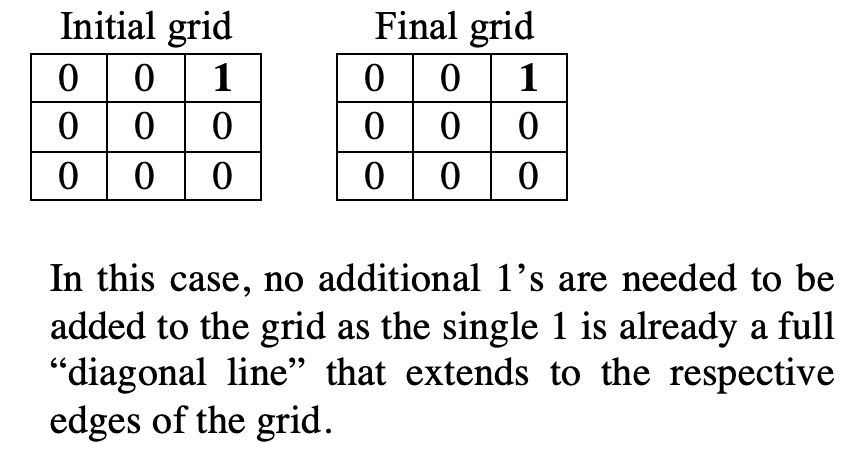

Below, we give two additional examples of initial/final grids to help further clarify specific cases:

The starter code is provided below.

def diagonal_line(grid):

#

Problem 4: Images (30 points)

As we talked about in class, an image is just a grid of pixels. There are many applications (such as techniques to blur an image) that require us to compute average values over subsections of such an image. Specifically, if we are given an image, we want to compute a new** image of the same size where each pixel in the new image has a red, green, and blue value that is the average of the respective red, green, and blue values in a 3 by 3 neighborhood of pixels in the original image. For example, say we have the following image that is 5 by 4 pixels in size (annotated by row and column indexes), where we show the red, green, and blue values in each pixel in parentheses as (red value, green value, blue value):

We would want a function that returns a new image, where the color in every pixel (at location (row, column)) in the new image is the average of the colors in the nine pixels immediately around and including the pixel (at location (row, column)) in the original image. The average color is computed by setting the red value of the pixel to the average of the red values for the nine pixels around it, and similarly for the green and blue values.

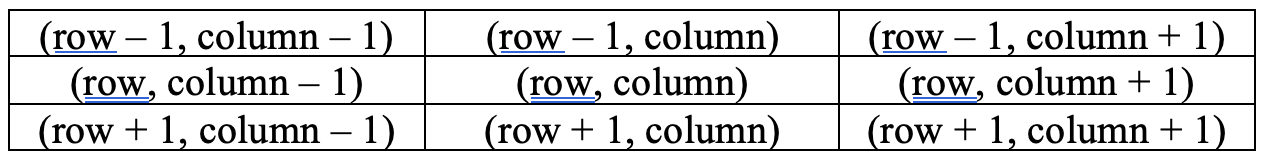

To be explicit, the color in pixel (at location (row, column)) in the new image should be the average of the colors in the sub-grid of the original image defined by the pixels with indexes shown below:

So, given the 5 by 4 pixel image above, in the resulting blurred image, the pixel at location (2, 1) would have red, green, blue values (30, 40, 50). These values would have been computed as the average of the respective red, green, and blues values from the pixels in rows 1 to 3 and columns 0 to 2 from the original image (this neighborhood is highlighted by the heavy outline in the example above). For example, the red value is computed by averaging the nine values 30, 60, 50, 20, 10, 10, 70, 10, and 10, which is 30.

Note that if computing the average value for a pixel would require the use of pixels that are off the edge of original image, then the average should just be computed with the neighboring pixels that are available on the image. For example, to compute the color for the pixel that is at location (0, 0), we would average only the four pixels at locations (0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), and (1, 1) from the original image (since there are no pixels at row or column with index -1 in the image). For example, computing the new pixel for location (0, 0) in the image above should have the red, green, blue values (30, 40, 20).

The header for your function should be:

def create_blurred_image(img)

Your function should not change the the original image passed in. It should return a newly created (blurred) image. You may assume that the image passed to your method contains at least one pixel. You only need to write the create_blurred_image function, not a complete program. You can also write helper functions, if that helps you solve the problem. The starter code is provided below.

def create_blurred_image(img):

#

Problem 5: Strings (20 points)

In the early part of the 20th century, there was considerable interest in both England and the United States in simplifying the rules used for spelling English words, which has always been a difficult proposition. One suggestion advanced as part of this movement was the removal of all doubled letters from words. If this were done, no one would have to remember that the name of the Stanford student union is spelled "Tresidder," even though the incorrect spelling "Tressider" occurs at least as often. If double letters were banned, everyone could agree on "Tresider."

Write a function remove_doubled_letters that takes a string as its argument and returns a new string with all doubled letters in the string replaced by a single letter. For example, if you call

remove_doubled_letters('tresidder')

your function should return the string 'tresider'. Similarly, if you call

remove_doubled_letters('bookkeeper')

your function should return 'bokeper'.

In writing your solution, you should keep in mind the following:

-

You do not need to write a complete program. All you need is the definition of the function remove_doubled_letters that returns the desired result.

-

You may assume that all letters in the string are lower case so that you don't have to worry about changes in capitalization.

-

You may assume that no letter appears more than twice in a row. (It is likely that your program will work even if this restriction were not included; we've included it explicitly only so that you don't even have to think about this case.)

The starter code is provided below:

def remove_doubled_letters(str):

#