1) Examine recursive stack frames

The factorial n! is defined as the product n * (n-1) * (n-2) * ... * 3 * 2 * 1. The recursive approach to computing factorial uses the insight that:

- factorial

0!is defined to be1 - factorial

n!can be computed asn * (n-1)!

Recall that the former is the base case, the latter is the recursive case.

Review the provided code for the factorial function in warmup.cpp that implements the recursive structure described above. We will use this function as practice for examining recursive stack frames.

Set a breakpoint on the return statement within the base case of factorial. Run the program in Debug mode. When prompted, select the tests from warmup.cpp to run.

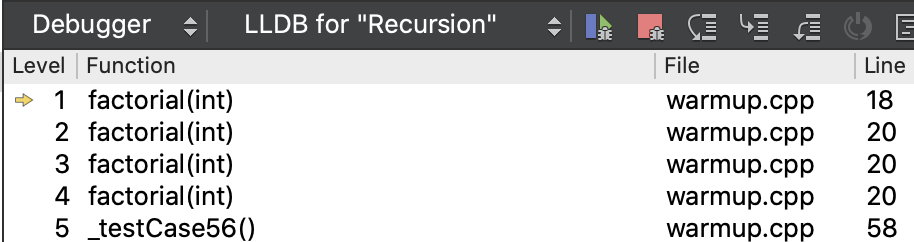

When stopped at the breakpoint, the lower middle pane of the debugger window shows the call stack. This is a list of the active functions up to the point where the breakpoint was reached. Each line in the call stack corresponds to a function that has been called and not yet finished executing.

The innermost level (Level 1) is the currently executing function. It was called from the function at Level 2, who was called from Level 3 and so on.

The small yellow arrow next to Level 1 indicates that this function is currently selected. In the rest of the debugger window, the Editor pane shows the source lines for the currently selected function and the Variables pane displays the value of the parameters and variables for the selected function.

Click on the function at Level 2 in the call stack, and the yellow arrow moves to indicate this function is now selected. The Editor pane and the Variables pane update to show the source and variables corresponding to this function. Click to select Level 3, and then Level 4. As you move through the levels, look to the Variables pane to see that each recursive call has its own independent variables that are distinct from the variables of other calls.

Each active function on the call stack has a place designated in the computer's memory to store its parameters and variables. The function's storage is called its "stack frame".

When you are stepping through recursive functions, be sure to keep an eye on which level of the recursion you are examining and pay careful attention to avoid getting confused by the different stack frames of the recursive calls.

Q1. Looking at a call stack listing in a debugger, what is the indication that the program being debugged uses recursion?

2) Recognize stack overflow

The provided test case for factorial only tries positive inputs, but what about negative? Consider the call factorial(-7). What should that evaluate to? Trace the code and predict will happen when executing that call.

Add a student test that calls factorial(-7) and expects an error. Run the tests normally, not in Debug mode. What you should expect to see is that instead of throwing an error and passing the test, the program unceremoniously exits in the middle of the test with no explanation as to what just happened!

In the past when our programs have raised an error, SimpleTest caught the error and reported it with a helpful message. But this particular error, stack overflow, is too slippery to be tamed. A stack overflow occurs when a function recursively calls itself without end. As each invocation requires storage space for its stack frame, the unceasing growth of stack frames eventually exhausts the total amount of memory set aside for the call stack.

For ordinary errors, our libraries can detect and report the problem and perhaps even gracefully recover. But the catastrophic nature of stack overflow in C++ results in a hard, unavoidable program crash. Looking at the Application Output tab offers no further information than a terse mention that the program "unexpectedly quit" or "ended forcefully".

This is an opportunity for the debugger to save the day! By running under the debugger, you gain the ability to stop at the time of the crash and use the debugger to inspect the program state at the critical moment.

Re-run the program in Debug mode. Don't set any breakpoints. Run the same test that previously crashed the program. At the point of the stack overflow, the debugger will stop the program and activate the debug window. One key place to look is at the call stack which shows where the program was executing at the time of the crash. This tells you what steps led up to the crash. In this case, the call stack is filled with level after level of the same recursive function calling itself non-stop. This call stack is the evidence that clearly shouts out "Uh oh, stack overflow!".

This will probably not the be last time you need to diagnose a stack overflow, so learn how to recognize it!

Q2. What is the value of parameter n at the innermost level (Level 0 or Level 1, depending on your system)? What is the highest numbered level shown in the call stack? (you may have to drag the column divider to enlarge the column width to fit all the digits) The range between the two gives an estimate of the capacity of the call stack on your system.

Note: There are two oddities that you may encounter when examining a call stack during a stack overflow condition. The first is that the variables of the innermost frame may have unreliable values. The innermost frame was the final straw that broke the camel's back. The crash occurred while adding this frame, interrupting the process of initializing the parameters and variables. In such a case, instead look at the fame that is one level further up to see reliable values. The second oddity is that if you scroll down to find the outermost frame, you may run into an abrupt end before reaching the true bottom of the callstack. This is Qt Creator applying its own cap on the number of frames to display. Those extra frames you're looking for do exist, but Qt is simply not displaying them.

In the warmup of last week's assignment, you used the debugger to diagnose the symptom of an infinite loop. Above you have just learned to diagnose infinite recursion. Although the root cause to both errors is somewhat similar (a repeating process that fails to terminate), they present with different symptoms.

Q3. Describe how the symptoms of infinite recursion differ from the symptoms of an infinite loop.

Now, edit the code of factorial function to call error if given a negative argument. Add a student test that uses EXPECT_ERROR to confirm that factorial of a negative number is rejected. Re-run to confirm that your fix has corrected the previous infinite recursion, no more stack overflow, and even provides a helpful message to the user of what went wrong. Much better!

3) Testing a recursive function

The warmup.cpp file contains two functions to compute raising a base to a power. The iterativePower function uses a loop and the power function operates recursively. The code for iterativePower is correct and was provided so you could use it to test the buggy power function. We recommend reading through the code in both functions to make sure you understand each approach.

Now let's practice using iterativePower as a cross-comparison to test the buggy recursive power. A simple approach is to call the two functions passing the same arguments and compare the results for equality:

PROVIDED_TEST("Test recursive power against iterative power") {

EXPECT_EQUAL(power(7, 3), iterativePower(7, 3));

}

A somewhat fancier approach is to use a loop to run a large number of trials, selecting random values for the inputs. Every time you run this test, the values are randomized again, so running this test gives wider coverage than a fixed set of manually chosen inputs. This is our first encounter with generating random numbers in C++. Luckily, the Stanford C++ libraries provide handy functions to help with this task. We'll be making use of the randomIntegerfunction from the random.h header file.

PROVIDED_TEST("Test recursive power against iterative power, random inputs") {

for (int i = 0; i < 25; i++) {

int base = randomInteger(1, 20);

int exp = randomInteger(0, 10);

EXPECT_EQUAL(power(base, exp), iterativePower(base, exp));

}

}

The above loop test only tries non-negative numbers for base and exp. Add a student test of your own that instead selects random negative numbers for base and another student test that selects random negative numbers for exp.

Running your new tests should show that a negative base is no problem, but there is the occasional test failure that pops up among the negative exp. Depending on randomness, it may take a few tries to expose the problem. If you get stuck on this, make a post on Ed asking for a hint about how to construct your tests so as to surface the bug. As a general strategy, think about a mix of targeted versus broad coverage. Given that issues often lurk at the boundaries, be sure to intentionally test the exponents right at transition between negative and positive, as well as trying a random smattering of values from a wider range. While you're trying to identify the bug, it may also help to compare and contrast the iterative and recursive implementations to identify where their results differ.

The test failure message doesn't indicate the specific input values that fail, but if you add your own cout statement to output base and exp just before EXPECT_EQUAL this will give a running commentary about the inputs being tested. Look for the last input printed before the test failure; this is the input that triggered the failure. Run the tests a few times and note which values result in failure. A pattern should emerge regarding the inputs that fail.

Q4. What are the specific values of base/exp that result in a test failure?

Now that you know which specific inputs trigger a failure, write a student test that you can use to reliably reproduce the failure. Don't worry about fixing the bug just yet, we'll do that in the next section!

4) Debugging a recursive function

As we discussed in lecture, a recursive function must be prepared to handle all of the different types of inputs that it might be given. However, the provided code for power seems to have gone a little bit overboard in this regard. There are currently four distinct base cases, which seems like a lot. Are they all truly needed? The best recursive design avoids unnecessary cases that overlap or are redundant. In this warmup, you'll see how piling on the extra base cases isn't just wasteful or stylistically poor, it can also introduce functionality bugs.

Before continuing on with more testing, step back and try to reason about the situation. Consider the test cases that you have added and the observations you have made when running those tests. Answer the following question before going on (please note that we're not looking for a "correct" answer here – we want to hear your honest impression before you dig in deeper):

Q5. Of the four base cases, which do you think are redundant and can be removed from the function? Which do you think are absolutely necessary? Are there any base cases that you're unsure about?

Now, let's settle that question once and for all with further testing to confirm the necessity (or not) of each base case.

Take a look at the special-case base cases that handle exp == 1 and exp == -1. Trace the code and predict what would happen if you entirely removed these cases. Comment out those cases and rebuild and run the program to see if your prediction was correct.

You will discover that removing those cases not only cleans up the design, it also resolves the test failure with negative exponents. That's what I call a win-win!

Q6. First explain why those cases were redundant/unnecessary and then explain why removing them fixed the test failure. (Hint: Consider the types of the values in play here and think about what happens when you do division with integers.)

Now that you are down to two base cases, you wonder if you can streamline to just one. The case for exp == 0 seems essential, but the special case for base == 0 seems a bit suspect.

Zero raised to any exponent should be zero, right? Add a student test case to confirm the test below passes for any value of exp:

EXPECT_EQUAL(power(0, exp), 0);

Now predict what will happen if you remove the special handling for base == 0. It will fall through to the existing general cases, which seem to plausibly handle a zero base without making special arrangements.

However, the rub is going to come for a negative exponent. First trace by hand the operation of raising 0 to a negative power assuming no special handling for base == 0. Now edit the code to remove the case for base == 0 and run your test again to observe what happens when the computer tries it.

Q7. What is the result of attempting to compute 0 raised to a negative power without a special case for base == 0?

Okay, so maybe base == 0 will require some delicacy for its unique situation, which means that it should be included as its own separate base case. Good to know!

The final oddball case is zero to the power of zero for which there is unresolved debate of whether the correct result is 0 or 1. You can simply raise an error for that!

Save the modified file with your additional test cases and fixed code. Be sure to include your edited warmup.cpp as part of your assignment submission.