What is a Priority Queue?

A standard queue processes elements in the first-in, first-out ("FIFO") manner typical of ordinary waiting lines. New elements are added to the back of the queue and the next element to be processed is taken from the front. Queues are a very useful abstraction, but a FIFO strategy isn't always what is needed.

A hospital emergency room, for example, needs to schedule patients according to priority. A patient with a more critical problem will pre-empt others that arrived earlier. The data structure that supports this behavior is called a priority queue. Each element is enqueued with an associated priority and dequeue retrieves the element with the most urgent priority. There are many practical applications for a priority queue, both inside and outside of computer science!

PQSortedArray interface

A C++ class is the perfect way to provide this new collection type. The PQSortedArray class has a simple, clean interface expressed in high-level operations such as enqueue and dequeue. All the messy internal details (handling dynamic memory, organizing the data, finding the most urgent priority and so on) can be neatly tucked away inside the class implementation. Rather than relying on the Stanford library to provide that implementation as you have in the past, this time you will cross behind the wall of abstraction to build the implementation yourself.

The interface for the PQSortedArray class is shown below. It is nearly identical to that of the standard Queue. The only operational difference is the element retrieved by peek/dequeue is the element of most urgent priority rather than one that was enqueued first.

In an ideal world, the priority queue would allow the client to set the element type like the Stanford collections do (that is, you can choose whether you want a Queue<int> or Queue<string>), but the C++ language features for templates/generics go a bit beyond the scope of what we've learned. Instead we will fix the element type to always be a DataPoint that bundles a string name with an integer priority. We introduced the DataPoint struct in the warmup and reproduce its type declaration below:

struct DataPoint {

string name;

int priority;

};

Important Note: The

priorityfield is an integer value. A smaller integer value indicates a more urgent priority than a larger integer value. The DataPoint with the minimum integer value for priority is treated as the most urgent and is the one retrieved by peek/dequeue.

class PQSortedArray {

public:

PQSortedArray();

~PQSortedArray();

void enqueue(DataPoint element);

DataPoint dequeue();

DataPoint peek() const;

bool isEmpty() const;

int size() const;

void clear();

void printDebugInfo();

void validateInternalState();

private:

DataPoint* _elements;

int _numAllocated;

int _numFilled;

};

PQSortedArray implementation

While the eventual goal is to implement the Priority Queue using a fancy high-performance data structure, you will first work with a simpler implementation that stores the elements in a sorted array. This task will acclimate you to the Priority Queue interface and the code to implement a C++ class and give you practice using dynamic memory and manipulating arrays.

We start you off with a mostly-complete implementation of this PQSortedArray class. Your first job is to carefully review this provided code. Read over the class interface in pqsortedarray.h and then proceed to the class implementation in pqsortedarray.cpp. Confirm your understanding of the existing design and code by answering the following questions in short_answer.txt:

Q5. There are extensive comments in both the interface (qsortedarray.h) and implementation (pqsortedarray.cpp). Explain how and why the comments in the interface differ from those in the implementation. Consider both the content and audience for the documentation.

Q6. The class declares member variables _numAllocated and _numFilled. What is the difference between these two counts and why are both needed?

Q7. Detangle the expression in the last line of the dequeue function and explain how it returns and removes the most urgent entry from the queue.

Your task

The provided PQSortedArray class is mostly complete, save for the missing body of PQSortedArray::enqueue. Your task is to implement this member function. This operation adds a new element to the queue.

Your code must work correctly with the other provided operations unchanged. Before writing any code, be sure that you understand how the dynamic array is managed in the constructor/destructor and why the code in peek/dequeue requires that the array elements are stored in decreasing sorted order of priority value.

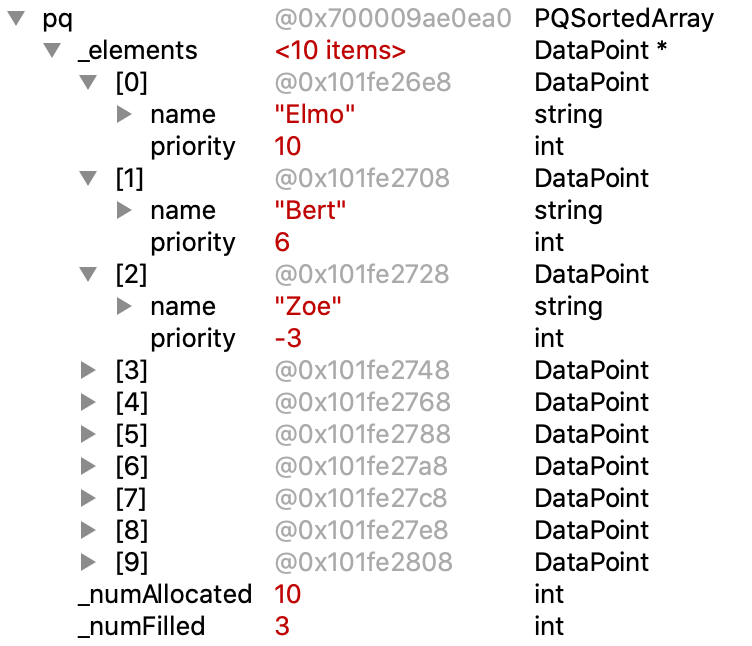

The sample client code below enqueues three elements into an empty queue.

PQSortedArray pq;

pq.enqueue( { "Zoe", -3 } );

pq.enqueue( { "Elmo", 10 } );

pq.enqueue( { "Bert", 6 } );

Here is a screenshot of the debugger displaying the internal contents of pq after executing the above code. The three elements are not stored in FIFO order, but instead in order of decreasing priority.

A subsequent call to pq.enqueue({"Kermit", 5}) would insert the new element between Bert and Zoe, updating the array contents to:

[0] = { "Elmo", 10 }

[1] = { "Bert", 6 }

[2] = { "Kermit", 5 }

[3] = { "Zoe", -3 }

The enqueue operation must find the correct position in the array to place the new element and move the other elements aside to make room for it. Your main task will be to find a generalized, robust way to do so, sharpening your array manipulation and dynamic memory skills along the way.

The other important job of enqueue is to grow the array to accommodate additional elements when it is filled to capacity. Growing the array is a mildly expensive operation, so it should only be done when needed and be opportunistic about anticipating future growth. When enlarging the array, you should make the new allocation twice as large as the previous capacity. This will provide storage for many additional elements before having to grow again.

The task of enlarging the array fits nicely in a helper function. Add a declaration of the helper function to the private section of the class interface and define it as part of the class implementation. You can then call the helper from enqueue when needed.

Implementation requirements

- You should not change the code for any other functions other than

enqueue. However, you may add any private helper functions that you might find useful (i.e. to resize the array, insert elements into the correct location, etc.) - Enqueue should not operate by tacking the new element onto the end and re-sorting the entire array. The elements in the array are already sorted and do not need rearrangement (and doing so adds necessary work). Instead the enqueue operation should place the new element into the already sorted array, sliding over elements to open up a space at the correct position.

- Revisit Monday's lecture to review Chris's clever hermit crab analogy and how to translate into C++ code to expand the capacity of a dynamic array. This is a small but tricky operation – ask questions to be sure you understand each step in the process.

- The class is responsible for proper allocation and deallocation of dynamic memory. Take care to properly deallocate any memory that is no longer is needed, such as when outgrowing a piece of memory or in the class destructor.

Testing across the abstraction boundary

The abstraction boundary that separates the client's use from the internals of the implementation is a great benefit for managing complexity, but when trying to develop and debug that implementation, that separation can be a bit of nuisance. Here are some suggestions for how to straddle that boundary and test the internal behavior of a class from client code.

- Many test cases can be structured to stay entirely client-side. For example, after clearing the queue, you can check that it is empty and size is zero. If you can confirm what you need using the functions of the public interface, your test case will not need to dig around in the internals. Where possible, this is a good strategy.

- For some operations, most notably enqueue and dequeue, testing solely client-side is limiting. It is essential that these operations properly maintain the internal array in sorted order, but the client doesn't have access to the array contents to confirm. What your test cases need is some kind of "backstage pass". Our provided code defines a

validateInternalStatedebugger helper as part of the class. It uses its insider access to examine the array and verify the sorted property, raising an error if it encounters a problem. One of the provided tests demonstrates making calls tovalidateInternalStatebetween operations to watch for any corruption in the internal state.- You could even add a call to

validateInternalStateas part ofenqueueto automatically verify that every enqueue correctly preserves the internal state. You would only want to add such a call temporarily and remove once your debugging is complete to avoid degrading performance.

- You could even add a call to

- The debugger is another way to get a backstage pass The client code cannot directly access the class internals, but you can stop in the debugger and freely examine those variables in the

Variablespane. - Another option is to define a debugger helper to be used as a a "data dumper". Our provided code demonstrates this technique in the

printDebugInfowhich outputs the contents of the internal array. One of the provided tests callsprintDebugInfoafter an operation to get visibility of what's happening behind the scenes. A dumper function is largely equivalent to using the debugger to examine the array contents, so if you're already pretty skilled with the debugger, you may not want to bother with adding a manual data dumper. - Check out the provided tests to see suggested ways to apply these techniques. You should also supplement with your own student tests to ensure the coverage is robust and comprehensive. With passing results on all these tests, you can now be confident that your implementation is fully correct, inside and out.

Timing analysis

With a completed and fully-tested class, the final task for PQSortedArray is an analysis of its efficiency . First, predict what you expect the Big O of enqueue and dequeue to be (hint: these predictions should match the requirements stated in the comments in pqsortedarray.h) and follow up with a timing analysis to confirm your prediction.

A call to enqueue/dequeue operation runs quite quickly and our timers are not precise enough to reliably measure the time spent in a single operation. Instead, we run many, many operations and measure the total time for all. The starter code provides the helpful functions fillQueue and emptyQueue, which run n total enqueue/dequeue operations respectively. Helpful hint: n represents both the total number of operations and the final (worst case) size of the queue – think carefully about how this might impact the timing results you observe.

Use the SimpleTest timing operations to measure the execution time of enqueue and dequeue over 4 or more different size inputs. Choose sizes so that the largest operation completes in under a minute or so. Because dequeue runs much faster than enqueue, you may have to choose a different range of sizes for the enqueue and dequeue operations.

Answer these questions in short_answer.txt:

Q8. Give the results from your time trials and explain how they support your prediction for the Big-O runtimes of enqueue and dequeue.

Q9. If the PQSortedArray stored the elements in increasing priority order instead of decreasing priority order, what impact would this have on the Big-O runtimes of enqueue and dequeue?

Addendum: debugging memory errors

When your code makes a memory error (writes out of array bounds, access deallocated memory, etc.) the consequences can vary widely –everything from spectacular immediate crash to hang to garbage output or the insidious situation where everything appears fine but lies in wait. This last one "silent-but-deadly" is the worst– some part of memory has been corrupted and it only surfaces in some later, seemingly unrelated situation.

For a dynamic array, common sites for errors are in enlarging the array or edge cases such as the last add before enlarge or first add after enlarge. One tactic that may help to isolate the faulty code is to change your constructor to make an enormous initial allocation (big enough to cover the largest of your test cases with room to spare). This change will cause your enlarge code to not be used at all. If after making this change, all the test cases pass in all situations, then you know to focus your attention on enlarge. Now change your initial allocation to 1 and grow by 1 each time (rather than double capacity), your enlarge code is going to get a tremendous workout . Run the test cases again and any bug in enlarge will have nowhere to hide.

Be vigilant about staying within the allocated bounds of your array. There's nothing that will stop your code from reading or writing to an index outside allocated array bounds (e.g. at index[-1] or index[count]) other than your own vigilance. These errors can be nasty. It is possible for an out of bounds write to corrupt the memory housekeeping in such a way that it crashes on a subsequent new/delete operation. The distance between the time the error was made and the observed consequence can be particularly confounding. Adding a helper function that confirms an array index is in bounds before accessing and faithfully using it on every array access would work wonders to avoid such bugs.

Another common cause of memory errors is incorrect deallocation. If you suspect this in your code, comment out every call to delete and delete[] and re-test. If disabling deallocation "fixes" all your errors, you know to drill down into you deallocate. Reintroduce those delete calls one a time and re-test to pinpoint which is the one causing the trouble.

Erroneously accessing deallocated memory is another pitfall. When you call delete, the system marks the memory location as available for recycling, but often leaves the contents there. If you access it and see your contents, you mistakenly believe all is well.

I use the analogy of you telling the front desk that you are checking out of your hotel room but keeping your room key. If the hotel doesn't change the locks, it is okay for you to use your room key (pointer) to go back to the room and pick up that toothbrush that you forgot? If you went back quickly enough, you might find your stuff right where you left it, but eventually housekeeping will sweep the room and the room will be re-assigned and you certainly don't want to walk into someone else's room looking for your stuff. It is your job to do the right thing: don't deallocate memory until you are sure you are done with it and don't access it after you have deallocated it.

All of this is tough stuff – C++ puts a lot of control in your hands and gives you little help in detecting/diagnosing the error. Be systematic, use test cases, work on small bits of code at a time, and make use of your awesome debugger skills. You will learn a lot by working through these difficult bugs and gain a deep appreciation of the responsibility that comes with this power.