The power of lists

One of the major advantages of linked lists over arrays is the flexibility and efficiency with which we can reorder elements. Arrays are stored in contiguous memory and rearranging elements is a tedious process of copying elements one by one, as you may remember from implementing PQSortedArray. In contrast, all that's needed to insert or remove a node within a linked list is re-assigning a pointer or two. A task like sorting that does a lot of rearrangement gains a distinct advantage when operating on a linked list instead of an array.

Your task for this part of the assignment is to write two different routines to rearrange the nodes of a linked list into sorted order. The first uses a run-based merging sort and the second is an implementation of the classic Quicksort algorithm. This exercise will give you great practice with pointers and linked structures and deepen your understanding of sorting algorithms.

A focus on testing

Before you start in on writing code, you will first consider what infrastructure you will need to test the code you plan to write.

In previous assignments, we provided a starting set of tests, along with any utility functions used as test infrastructure. As your testing skills have grown, you have relied less on our provided tests and taken more ownership for developing test cases. For this assignment, you will further take on the responsibility to develop your own utility functions that will serve as the infrastructure when writing your test cases.

Utility functions

Utility functions that create, compare, and output a linked list are essential components of any testing strategy. We suggest these four utility functions in the starter code:

-

void printList(ListNode* front)This "data dumper" function traverses a given linked list and prints the data value in each node. You could manually follow the pointers using the debugger to view those data values (as you did when searching the labyrinth), but it is more convenient to call a function to print the list in one go. You can call this utility function anywhere within your code or test cases as a debugging aid. This function is provided for you fully-implemented and working. Please make good use of it!

-

void deallocateList(ListNode* front)This utility function deallocates the memory for all the nodes in a given linked list. It can be used to recycle the memory allocated during a test case and avoid memory leaks.

-

ListNode* createList(Vector<int> values)This utility function is given a vector of values and constructs an equivalent linked list containing the same values in the same order. It can be used to construct a linked list to use as an input to a function being tested.

-

bool areEquivalent(ListNode* front, Vector<int> v)This utility function compares a linked list and a vector for equivalence and returns

trueif both contain the same values in the same order. It can be used to confirm a linked list's contents match the expected.

The last three utility functions are declared in the starter code and left for you to implement. Although it is not a strict requirement that you implement the utility functions according to the above specification, you will absolutely will need some form of utility functions, so please take our strong recommendation to implement the utility functions as your first task. Not only are the utilities a critical help for your later testing needs, writing them now is a great exercise in learning the standard linked list operations: traversing, connecting nodes, and allocating and deallocating lists.

You might ask: should I use iteration or recursion to implement my linked list functions? For certain tasks, one approach may be tidier, but in many cases either can work well. However, recursion has a very significant drawback. The cost of a stack frame for every node in the list adds a heavy performance cost and limits the total length of list that can be processed.

Q6. If the deallocateList utility function were implemented recursively, give a rough estimate of the maximum length list it could successfully handle. (Hint: refer back to your investigations for the warmup in Assignment 3.) What would be the observed result from attempting to deallocate a list longer than this maximum?

Because we want our sorting routines to be able to scale up to very long lists, you must choose an iterative approach for the utility functions, not recursive.

Test throughly! The utility functions need to be rock solid as they are the bedrock on which all your later tests will be built. We provide a sample test that demonstrates how you might test the utility functions. Modify and augment that test as needed to establish 100% confidence in these functions before moving on.

Note: The utility functions are similar to operations that have been shown in lecture and section. You are welcome to borrow from our published code, but be sure to make a clear citation. Whenever your submission contains code that was not authored by you, it must be cited.

Allocation, deallocation and memory leaks

The sort operations do not allocate or deallocate nodes; they simply rearrange nodes within an existing list. However, your test cases do allocate and deallocate lists to use as test inputs. A typical test case will create a list using createList, pass the list as the input to the function being tested, compare the result list to the expected using areEquivalent, and then use deallocateList to recycle the the list memory. To avoid reports of memory leaks, all memory allocated during the test case must be properly deallocated at the end of the test case.

Be mindful when writing your test case that the function being tested may rearrange the lists into a different configuration that you started from, thus you will need to work out which steps are needed to properly deallocate afterwards. For example, a test case may create two input lists, but after passing the lists to merge, they have been joined together, so there is just one list to deallocate. Similarly, a test case that creates one list and passes to partition will end up with three separate lists, each of which need to be individually deallocated.

Incremental testing

Although the ultimate goal of your test cases is to confirm that your sort functions work at a high-level (i.e. rearrange the list into sorted order), such tests will not be useful early in your development, when you need a different kind of test.

As you write each sort helper function such as merge or partition, you should add targeted tests that exercise that helper in isolation. Adding these tests allows you to confirm the correctness of the helper before moving on.

End-to-end tests

The final step in your testing strategy is adding the end-to-end tests to confirm the top-level sort functionality. We have provided an example STUDENT_TEST "skeleton" that you may want to use as a template for your student tests.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of suggested test cases to consider when building your comprehensive test suite:

- Sorting an empty list

- Sorting a single-element list

- Sorting a list in already sorted or reverse sorted order

- Sorting a list that contain some duplicate elements or all duplicate elements

- Sorting a list that contains positive and negative numbers

- Sorting a list of random values, randomly organized

- Sorting a very long list

The quality and breadth of your test cases will be an important component of the grading for this assignment. We're hoping you are ready to show us how much you have learned from the different testing exercises and provided tests that you've seen on the earlier assignments!

Your task

Your task is to implement two different linked list sorting routines. For an introduction to sorting algorithms, refer to last Friday's lecture on sorting and Chapter 10 of the textbook. The rest of this handout assumes familiarity with that content and does not repeat it.

The two functions are you to implement are:

void runSort(ListNode*& list)

void quickSort(ListNode*& list)

Each rearranges the nodes of list into sorted order. The first implements a run-based merging sort and the second is an implementation of the classic Quicksort algorithm.

RunSort

RunSort works by merging together sorted runs to create a sorted result, building from the bottom-up. The result list is initially empty and thus trivially sorted. The algorithm splits one sorted run from the input and merges it into the result. Then again: split another run from input and merge with the result. The process repeats until the remaining input is empty and result contains the final list.

Linked lists are a great fit for RunSort. Dividing a list or inserting an element requires only re-wiring a few pointers and none of the arduous shuffling or copying that is required when using an array/vector.

Your runSort should make use of two helper functions splitRun and merge. Each helper should be written and tested independently.

The merge helper function takes in two sorted lists and produces a single sorted list. You wrote a queue-based binary merge for Assignment 3, and this is a chance to re-implement that familiar task on a new data structure. Whereas that version had to copy elements from one queue to another, the linked list merge operates by re-wiring pointers.

Before writing any merge code, we recommend drawing lots of diagrams and tracing the algorithm on different inputs to keep track of all the pointers flying around. After implementing it, follow up to confirm that it works correctly using a comprehensive set of your own test cases. You may even be able to borrow some of the test inputs you used in Assignment 3 and re-purpose them here.

The splitRun helper function is used to break off a sorted contiguous sublist from the front of a list. For example, splitting a run from the list {3 -> 5 -> 5 -> 4 -> 10 -> 4} separates the list into the run {3 -> 5 -> 5} and remainder list {4 -> 10 -> 4}. Calling splitRun on the remainder list separates run {4 -> 10} from remainder list {4} and a final call to splitRun separates the singleton run {4} from an empty remainder list. The action to split a linked list is surprisingly trivial: after traversing to the last node in the sorted run, terminate the run with a nullptr to break the connection between the run and the list remainder. As always, add your own tests to confirm the correct behavior of splitRun in isolation before moving on.

With your thoroughly-tested helper functions merge and splitRun, the final step is to put them together into runSort. Start with an empty result list. At each step, split a sorted run from the remaining input list and merge the run into the result. Rinse and repeat until the remaining input list is empty. Voila, a fully sorted list!

Note that runSort is entirely iterative. It loops calling splitRun and merge until finished. Both of the helper functions splitRun and merge also must also be implemented iteratively . For the reasons mentioned earlier, recursion is not appropriate because of its performance cost and limitation on list length.

QuickSort

QuickSort is an example of a recursive "divide and conquer" algorithm. It divides the input list into sublists, recursively sorts the sublists, and then joins the sorted sublists into one combined whole. QuickSort is known as a "hard-divide-easy-join" algorithm because the bulk of its work goes into the complex division step with a trivial join to follow. The classic version of the algorithm divides the input list into sublists that are less than, equal to, or greater than a chosen pivot. After recursively sorting the sublists, they are joined in sequence.

Linked lists also are natural fit for QuickSort. Distributing the elements into sublists and concatenation is just pointer assignment with none of the contortions used to swap/shuffle those array elements.

Your quickSort should make use of two helper functions partition and concatenate. Each helper should be written and tested independently.

The partition step is where most of the magic happens. Choose the first element of the list as the pivot. Divide the elements into three sublists: those elements that are strictly less than the pivot, those that are equal to the pivot, and those that are strictly greater. The existing nodes are re-distributed into the sublists; do not allocate new nodes or make node copies. The order that the elements are placed into the sublist is of no consequence, you may do whatever is most convenient for your algorithm.

One complexity of partition is that the function needs to produce three separate lists as its result. In C++, the function return only can send back a single value, so you'll need to explore using pass-by-reference parameters (a reference to a pointer, oh my!) to communicate those results back to the caller.

Be sure you understand the action of partition and have drawn many diagrams and traced the algorithm before you attempt to write it. It is tricky code! Use comprehensive testing to ensure you have the details just right.

The concatenate helper is given three lists to join into one combined by adding the links in between. Attaching one list to follow the end of another is just one pointer assignment. Neat! Write test cases that confirm concatenate does its job correctly in all situations. Be sure to consider the case when one or more the lists is empty.

With your thoroughly-tested helper functions partition and concatenate, the final step is to put them together into quickSort. The partition helper is used to divide the list into three sublists. The less and greater sublists are then sorted with recursive calls to quickSort. The sublist of elements equal to the pivot is already trivially sorted. Then concatenate is used to join the three sorted sublists together in sequence. The last detail for you to work out is an appropriate base case and your QuickSort is ready to roll!

Note that quickSort does make recursive calls to itself to sort the sublists, its helper functions partition and concatenate helpers must be implemented using iteration, not recursion, in order to avoid exhausting the call stack when sorting longer lists.

Requirements for your sort routines

- Your sorts must operate solely by rewiring the links between existing

ListNodes. Do not allocate or deallocate anyListNodes (i.e. no calls tonewordelete). Do not replace/swap theListNodedata values. You may declareListNode *pointers to be used temporarily when changing links betweenListNodes. - Do not use a sort function or library to arrange the elements, nor any algorithms from the STL C++ framework.

- Do not create any temporary or auxiliary data structures (array, Vector, Map, etc.).

- Both of your sorts should be capable of sorting an input list of random values of effectively any length.

Answer the following questions in short_answer.txt:

Q7. The prototypes for both sort functions take a ListNode* by reference. Explain why the pointer itself needs to be passed by reference and what the consequence would be if it were not.

Analyzing runtime

The RunSort algorithm clocks in an unimpressive O(N^2) time in the general case, but is particular well-suited to sort inputs containing long runs that are sorted or nearly-sorted. It crushes these inputs in a very zippy O(N) time!

Q8. Run time trials and provide your results that confirm that RunSort is O(N^2) . Verify you can achieve O(N) results on inputs constructed to play to its strengths.

The QuickSort algorithm runs in a competitive O(NlogN) time in the common case. However, given an extremely lopsided partition at every step of the recursion, the algorithm will degrades into its worst case performance of O(N^2). What are those inputs that produce such unbalanced partitioning?

Q9. Run time trials and provide your results that confirm that QuickSort is O(NlogN) . Verify the runtime degrades to O(N^2) on inputs constructed to trigger the worst case behavior.

The Stanford Vector class uses the C++ std::sort which is an array-based O(NlogN) algorithm (Quick-insert hybrid). You can prepare the same input sequence once in array form and again as a linked list, and then time the operation of Vector sort versus your linked list sort on that sequence to compare the relative performance of sorting a linked list versus an array. What do you predict will be the outcome of the great sorting race? Try it and find out!

Answer the following questions in short_answer.txt:

Q10. Run the provided timing trials that compare your linked list QuickSort to a Vector sort on the same sequence and report the results. Who wins and why?

Advice

- Be sure you have completed both warmup exercises before starting on this task. If you ran into any trouble on the warmup, get those confusions resolved first. You want to have top-notch skills for using the debugger to examine linked structures and be well-versed in what to expect from memory errors and how to diagnose them.

- Correct use of memory and pointers requires much careful attention to detail. You'll likely benefit from drawing a lot of diagrams to help you keep track.

- To be sure your code is doing what you intend, you'll likely need to step in the debugger and examine the state of your lists as you go. In fact, you might find it most convenient to run in the debugger full time as you work on this project, as this gives you the best tools for analyzing what is going on in your program at any given moment. This is information you cannot get any other way.

- Draw out an intentional design from the start and follow a systematic development process, and you can absolutely triumph. But hacking up an attempt operating with incomplete understanding and hoping you can prod the code into working is likely to lead to headache and heartache.

Extensions

Here are some ideas for further exploration of list sorting:

- Add a smarter choice of pivot for QuickSort. A poor pivot (e.g. min or max of sequence) can significantly degrade performance. Confirm this by constructing an input to QuickSort that triggers this worst cast and run time trials to observe it degenerating to O(N^2). There are many neat approaches to combat this effect, see https://stackoverflow.com/questions/164163/QuickSort-choosing-the-pivot/ for starters.

- Research and implement an alternative sorting algorithm. There are lots of interesting options! To name a few:

- Selection Sort

- Insertion Sort

- Bubble Sort (but Obama recommends against)

- Comb Sort

- Shaker Sort

- Gnome Sort

- Block Sort

- Shell Sort

- Spread Sort

- Strand Sort

- Unshuffle Sort

Some of these are more suited to linked lists than others, so do some background research on the algorithm before deciding whether it would be a good one to tackle.

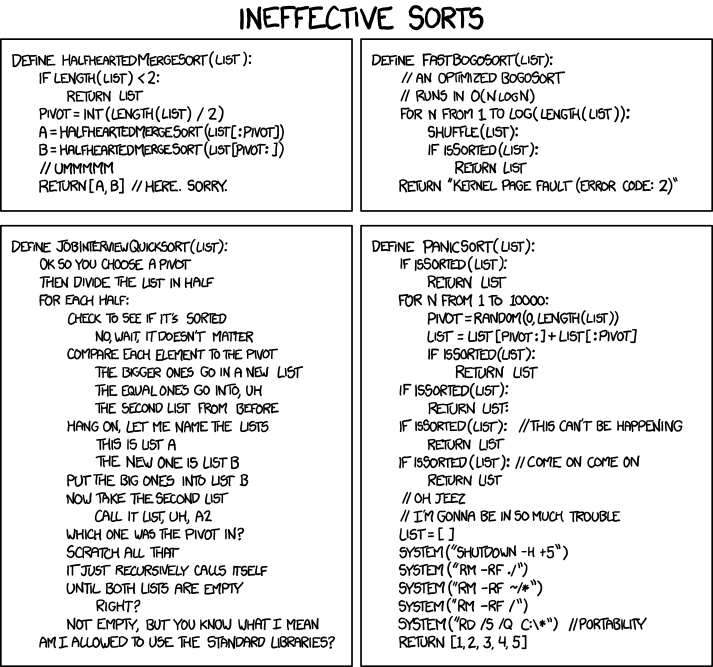

Courtesy of the always-wonderful xkcd.