Implementing StackInt

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Autumn 2020, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturers: Chris Gregg and Julie Zelenski

Hermit Crab (Pagurus bernhardus)

Hermit Crab (Pagurus bernhardus)

Slide 2

Announcements

- The Mid-Quarter Assessment is happening on Wed/Thurs this week.

- We will be distributing the exam questions using BlueBook. If you do not already have the BlueBook software installed on your computer, please follow the bluebook install instructions to get that set up.

Slide 3

Today's Goals:

- Introduction to Pointers

- More information on

delete - Destructors

- Implementing the Stack class

- Header File

- Implementation

- focus on

expand()

- More information on

Slide 4

Why do we care about delete?

- Now that we know a bit about pointers and memory management, we might wonder why

deleteis important. - Take a look at the following code:

const int INIT_CAPACITY = 1000000;

class Demo {

public:

Demo(); // constructor

string at(int i);

private:

string *bigArray;

};

Demo::Demo()

{

bigArray = new string[INIT_CAPACITY];

for (int i = 0; i < INIT_CAPACITY; i++) {

bigArray[i] = "Lalalalalalalalala!";

}

}

string Demo::at(int i)

{

return bigArray[i];

}

- If you look at the

Demo::Demo()function – that is a lot of strings!- 1MB array

*(20 chars + ~30 bytes of overhead for each string) = 50MB per class instance

- 1MB array

- If we then have this

mainfunction:

int main()

{

for (int i=0;i<10000;i++){

Demo demo;

cout << i << ": "

<< demo.at(1234)

<< endl;

}

return 0;

}

- We are now creating 10,000 instances of our 50MB class…we will use 2GB of memory!

- Let's see what will happen!

Slide 5

What happened?

- The program slowed to a crawl! We used lots of memory, and kept it!

- We call this problem a memory leak, and we want to avoid it. In other words: return the memory you don't need when you're done with it!

- Even though each of the 10,000 class instances went out of scope, without the destructor, we kept all the memory, and our computer started running out.

- Here is the destructor we need:

Demo::~Demo()

{

delete[] bigArray;

}

- Now, every time our class instance goes out of scope, we return the memory to the operating system, so we never have more than 50MB used at once. No more slowing down!

Slide 6

The StackInt class implementation

- In order to demonstrate how useful (and necessary) dynamic memory is, let's implement a Stack that has the following properties:

- It can hold ints (unfortunately, it is beyond the scope of this class to create a Stack that can hold any type)

- It has useful Stack functions: push(), pop(), peek(), isEmpty(), size(), « overload

- We can add as many elements as we would like

- It cleans up its own memory

Slide 7

Dynamic Memory Allocation: your responsibilities

- Back to Stanford Word.

- The problem we had initially was that Stanford Word can't just pick an array size for the number of pages, because it doesn't know how many pages you want to write.

- But, using a dynamic array, Stanford Word can initially set a low number of pages (say, five), and then … what can it do?

Slide 8

Expansion Analogy: Hermit Crabs

- Hermit crabs are interesting animals. The live in scavenged shells that they find on the sea floor. Once in a shell, this is their lifestyle (with a bit of poetic license):

- Grow a bit until the shell is outgrown.

- Find another shell.

- Move all their stuff into the other shell.

- Leave the old shell on the sea floor.

- Update their address with the Hermit Crab Post Office

- Update the capacity of their new shell on their web page.

- Grow a bit until the shell is outgrown.

- The hermit crab analogy is what we need to use dynamic arrays

- We can actually model what we want Microsoft Word to do with the array for its document by the hermit crab model.

- In essence, when we run out of space in our array, we want to allocate a new array that is bigger than our old array so we can store the new data and keep growing. These "growable arrays" follow a five-step expansion that mirrors the hermit crab model (with poetic license).

- One question: if we are going to expand our array, how much more memory do we ask for?

- double the amount – this is the efficiency trade-off we want.

- First, we don't have to double all that often (it is actually an expensive bit of code)

- Second, when we do double, we give our array a reasonable amount to grow, based on its current size

Slide 9

Dynamic array expansion steps

- There are five primary steps to expanding a dynamic array:

- Create a new array with a new size (normally twice the size)

- Copy the old array elements to the new array

- Delete the old array (understanding what happens here is key!)

- Point the old array variable to the new array (it is a pointer!)

- Update the capacity variable for the array

- When do we decide to expand an array?

- When it is full. How do we know it is full? We keep track!

Slide 10

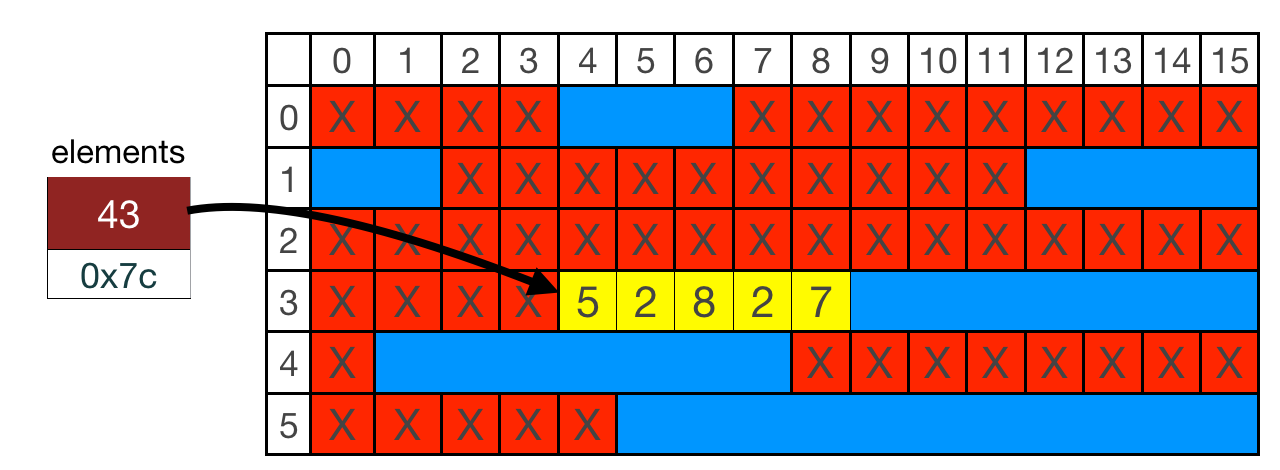

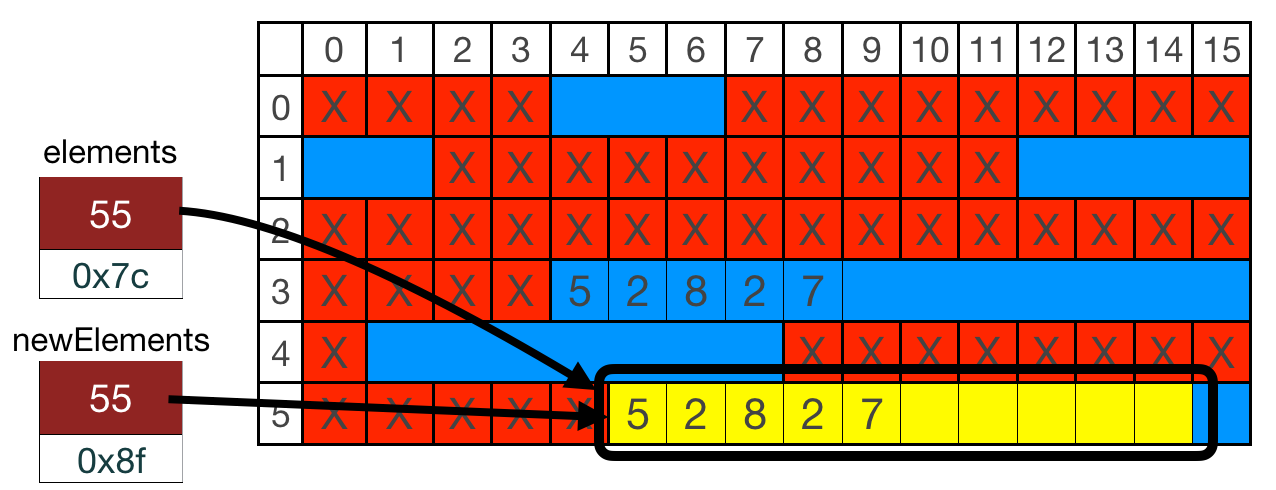

Stack Expansion: Memory

-

Let's say that our Stack's elements pointer points to memory as in the following diagram. capacity = 5, and count = 5 (it is full).

- To expand, we must follow our rules:

- Request space for 10 elements:

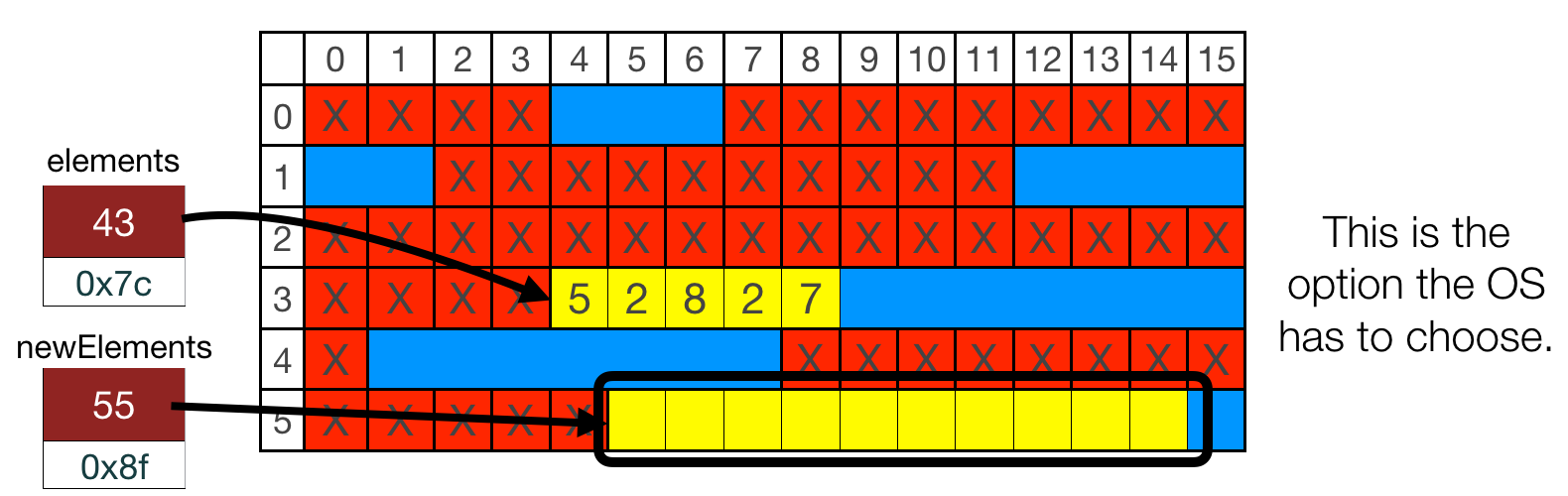

int *newElements = new int[capacity * 2];

- Request space for 10 elements:

- Where can we expand into?

- It looks like we can expand into the area starting at row 3, column 9, but we can't! We're already using row 3, column 4 through row three, column 8, and we can't simply ask the operating system to give us more memory in that location (actually, we can do that in C with a different set of memory operations, but not in C++ with

newanddelete). - We need to find a different location – there is enough space to double at row 5, column 5 (which is what the OS would pick for us)

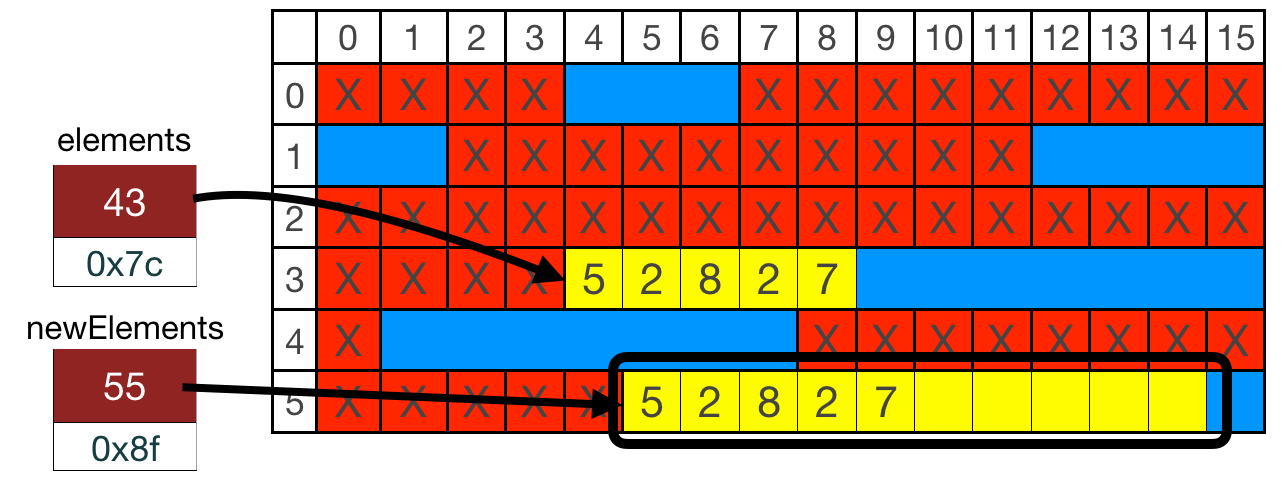

- We now copy the old data over to the new location (this is the expensive part of the procedure) (step 2):

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) { newElements[i] = elements[i]; }

- Step 3 is to return the memory:

delete [] elements; - Notice that we have now returned the memory to the OS – the values don't disappear, but we should not use the original location again:

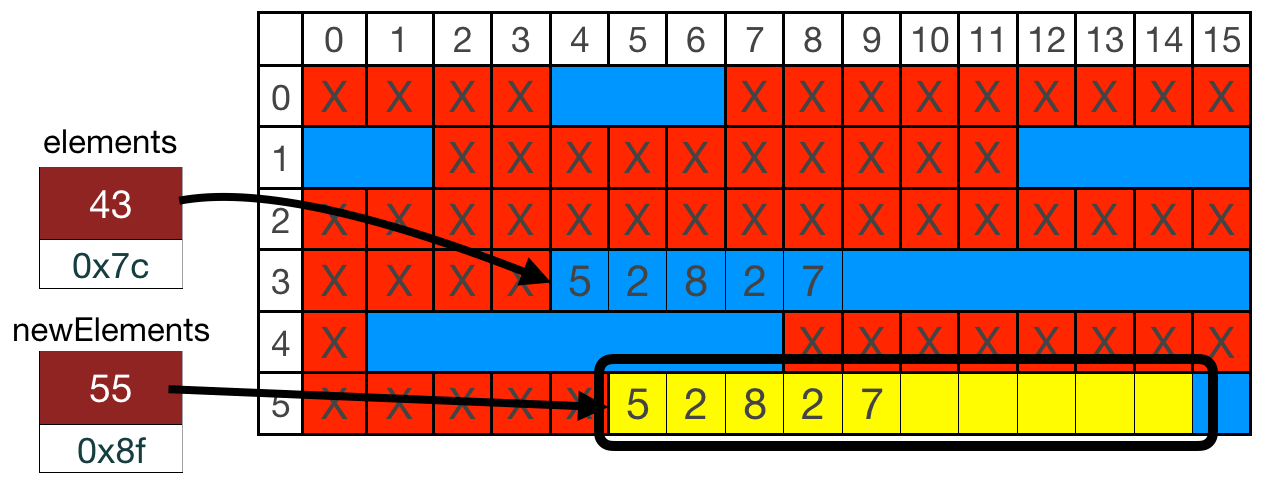

- Step 4 is to assign the elements to the new array:

elements = newElements;

- Finally, step 5 is our bookkeeping step, where we update the capacity:

capacity *= 2;

- It looks like we can expand into the area starting at row 3, column 9, but we can't! We're already using row 3, column 4 through row three, column 8, and we can't simply ask the operating system to give us more memory in that location (actually, we can do that in C with a different set of memory operations, but not in C++ with