Binary Heaps

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Autumn 2020, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturers: Chris Gregg and Julie Zelenski

Slide 2

Announcements

- The mid-quarter diagnostic started early this morning at 12:01am and will be continuing on through Thursday at 11:59pm. Three important action items:

- Download BlueBook in advance of your assessment and use the Sample Exam Questions to test that you are able to successfully load a BlueBook exam file.

- When you are ready to take the diagnostic, go to the distribution portal. You should be prepared to start the diagnostic within 5-10 minutes after you get your password and

.jsonfile from that page.

- Section is still taking place normally this week.

- Assignment 5 will be released today.

Slide 3

Today's Goals:

- Introduction to Binary Heaps

- A "tree" structure

- The Heap Property

- Parents have higher priority than children

- How to add and remove from a heap?

- Heaps can be used as a priority queue

Slide 4

Binary Heaps

- A heap is a tree-based structure that satisfies the heap property:

- Parents have a higher priority than any of their children

- There are two types of heaps: a min heap and a max heap.

- A min-heap has the smallest element at the root, and a "higher priority" is a smaller number. Thus,

5is a higher priority than10.5 / \ 10 8 / \ / \ 12 11 14 13 / \ 22 43 - A max-heap has the largest element at the root, and a "higher priority" is a larger number. Thus,

50is a higher priority than19:50 / \ 19 36 / \ / \ 17 3 25 1 / \ 2 7 - We will focus mostly on min-heaps, where the lower the number means a higher priority.

Slide 5

Binary Heaps

-

There are no implied orderings between siblings, so both of the trees below are min-heaps:

5 / \ 10 12 5 / \ 12 10

Slide 6

Which of the following are min-heaps?

5

/ \

10 8

/ \ / \

12 85 14 13

/ \

22 11

13

/ \

19 36

/ \ / \

24 99 46 42

/ \

25 26

- Answer: only the second one is a heap, because in the first one, the

11is a child of the12, and therefore it breaks the heap property that a parent has to be a higher priority than its children (remember: min-heaps designate higher priority as lower numbers).

Slide 7

Binary Heaps

- Binary heaps are completely filled, with the exception of the bottom level. They are, therefore, complete binary trees:

- complete: all levels filled from left to right except the bottom

- binary: two children per node (parent)

- Maximum number of nodes

- Filled from left to right

5 / \ 10 8 / \ / \ 12 11 14 13 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

Slide 8

How do you store a heap?

- It turns out that an array works great for storing a binary heap

- Later, we will see a much different approach to storing tree structures, but heaps (which also look like trees), the best solution is actually a simple array.

- The reason for this is because of the complete nature of the structure, with all levels filled from left to right.

5 / \ 10 8 / \ / \ 12 11 14 13 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __ - Here is the array for the above heap:

| values: | 5 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

- Notice that the array follows the levels, 5, then 10, 8, then 12, 11, 14, 13, then 22, 43 – this is the way we fill a heap.

- The array representation makes determining parents and children a matter of simple arithmetic:

- For an element at position i:

- The left child is at

2 * i + 1 - The right child is at

2 * i + 2 - The parent is at

(i - 1) / 2(integer math)

- The left child is at

heapSizeis the number of elements in the heap (for this heap,heapSizeis 9.

- For an element at position i:

Slide 9

Heap Operations

- There are three important operations in a heap:

peek(): return the element with the highest priority (lowest number for a min-heap). Don't change the heap at all.enqueue(e): insert an elementeinto the heap but retain the heap property! (we'll talk about this very soon)dequeue(): remove the highest priority (smallest element for a min-heap) from the heap. This changes the heap, and we have to return it to a proper heap.

Slide 10

Heap operations: peek()

5

/ \

10 8

/ \ / \

12 11 14 13

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 5 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

peek():- Just return the root!

return heap[0] - This is O(1) – yay, we love O(1)!

- Just return the root!

Slide 11

Heap operations: enqueue(e)

5

/ \

10 8

/ \ / \

12 11 14 13

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 5 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

- How might we go about inserting into a binary heap?

enqueue(9)into the heap above?- We have to think about this a bit. The key is to understand how heaps are built: fill each level from left to right.

- So, we start by putting the element as the left child of the 11. This probably destroys the heap property. We simply insert at

heap[heapSize]:5 / \ 10 8 / \ / \ 12 11 14 13 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 9 __ __ __ __ __

values: 5 10 8 12 11 14 13 22 43 9 ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - Now, to return the structure to a proper heap, we have to do an operation called "bubble up" – we take a look at the element we just added and compare it to its parent: in this case, we look at the 9 and its parent, 11. We see that this is not proper, so we swap them:

5 / \ 10 8 / \ / \ 12 9 14 13 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 11 __ __ __ __ __

values: 5 10 8 12 9 14 13 22 43 11 ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - We might not yet be done! We need to repeat the process until the element we added is either larger than its parent, or at the root. So, we compare the 9 to its new parent, the 10 (how do we know that from the array? 9 is at index 4, and (4 - 1) / 2 == 1, so we look at index 1 and find 10). Because the 9 is smaller than the 10, we have to keep bubbling up! We swap them:

5 / \ 9 8 / \ / \ 12 10 14 13 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 11 __ __ __ __ __

values: 5 9 8 12 10 14 13 22 43 11 ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - We must do one more comparison, between the 9 and its new parent, the 5. Because 5 is less than 9, we're done. If we look at the heap, we can see that it is proper again.

- What is the complexity? O(log n) – yay!

- It turns out that from random inserts, the average complexity is actually O(1). See http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?arnumber=6312854 for details.

- See the animation at http://www.cs.usfca.edu/~galles/visualization/Heap.html

Slide 12

Heap operations: dequeue()

- How might we go about removing the highest priority (minimum)?

dequeue()5 / \ 9 8 / \ / \ 12 10 14 11 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 13 __ __ __ __ __

values: 5 9 8 12 10 14 11 22 43 13 ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - We know where the minimum always is – at the root. So, we know that we will remove that element to return it. This will always destroy the heap, because it has no root!

/ \ 9 8 / \ / \ 12 10 14 11 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 13 __ __ __ __ __

values: -- 9 8 12 10 14 11 22 43 13 ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - Now, what do we know about the heap after we remove an element?

- We know it will be one element smaller. Where should that element come from?

- The last level, on the right! We know this will be an empty location at the end. So, what we do (and this may be counter-intuitive) is we take that element, and we put it at the root (the heap property will almost certainly be still destroyed):

13 / \ 9 8 / \ / \ 12 10 14 11 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

values: 13 9 8 12 10 14 11 22 43 ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - The next thing we do is a bubble down. We need to take the 13, and move it down.

- To bubble down, you swap the element in question with its smaller child (we have to do this because if we swapped with the larger child, we might still have a bogus heap from the root!). This means we swap the 13 with the 8, which is its smallest child:

8 / \ 9 13 / \ / \ 12 10 14 11 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

values: 8 9 13 12 10 14 11 22 43 ? ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - But we're not necessarily done! We look at the 13 and its children, again, and notice that we have to swap with the smallest child, the 11:

8 / \ 9 11 / \ / \ 12 10 14 13 / \ / \ / \ / \ 22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

values: 8 9 11 12 10 14 13 22 43 ? ? ? index: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 - When we check again, we see that 13 has no more children, so we have completed the bubble down.

- What is the complexity?

- O(log n) – yay!

- Heaps are a great data structure, becuase all the operations are either O(1) or O(log n).

Slide 13

Priority Queues

- Sometimes, we want to store data in a “prioritized way.”

- Examples in real life:

- Emergency Room waiting rooms

- Professor Office Hours (what if a professor walks in? What about the department chair?)

- Getting on an airplane (First Class and families, then frequent flyers, then by row, etc.)

- A priority queue stores elements according to their priority, and not in a particular order.

- This is fundamentally different from other position-based data structures we have discussed.

- There is no external notion of "position."

Slide 14

Priority queue functions

-

A priority queue,

P, has three fundamental operations:-

enqueue(k,e): insert an elementewith keykintoP. -

dequeue(): removes the element with the highest priority key fromP. -

peek(): return an element ofPwith the highest priority key (does not remove from queue).

-

- Priority queues also have less fundamental operations:

size(): returns the number of elements inP.isEmpty(): Boolean test ifPis empty.clear(): empties the queue.peekPriority(): Returns the priority of the highest priority element (why might we want this?)changePriority(string value, int newPriority): Changes the priority of a value.

- Priority queues are simpler than sequences: no need to worry about position (or

insert(index, value),add(value)to append,get(index), etc.). - We only need one

enqueue()and onedequeue()function

Slide 15

Priority Queue Example

| Operation | Output | Priority Queue |

|---|---|---|

| enqueue(5,A) | - | {(5,A)} |

| enqueue(9,C) | - | {(5,A),(9,C)} |

| enqueue(3,B) | - | {(5,A),(9,C),(3,B)} |

| enqueue(7,D) | - | {(5,A),(9,C),(3,B),(7,D)} |

| peek() | B | {(5,A),(9,C),(3,B),(7,D)} |

| peekPriority() | 3 | {(5,A),(9,C),(3,B),(7,D)} |

| dequeue() | B | {(5,A),(9,C),(7,D)} |

| size() | 3 | {(5,A),(9,C),(7,D)} |

| peek() | A | {(5,A),(9,C),(7,D)} |

| dequeue() | A | {(9,C),(7,D)} |

| dequeue() | D | {(9,C)} |

| dequeue() | C | {} |

| dequeue() | error! | {} |

| isEmpty() | TRUE | {} |

Slide 16

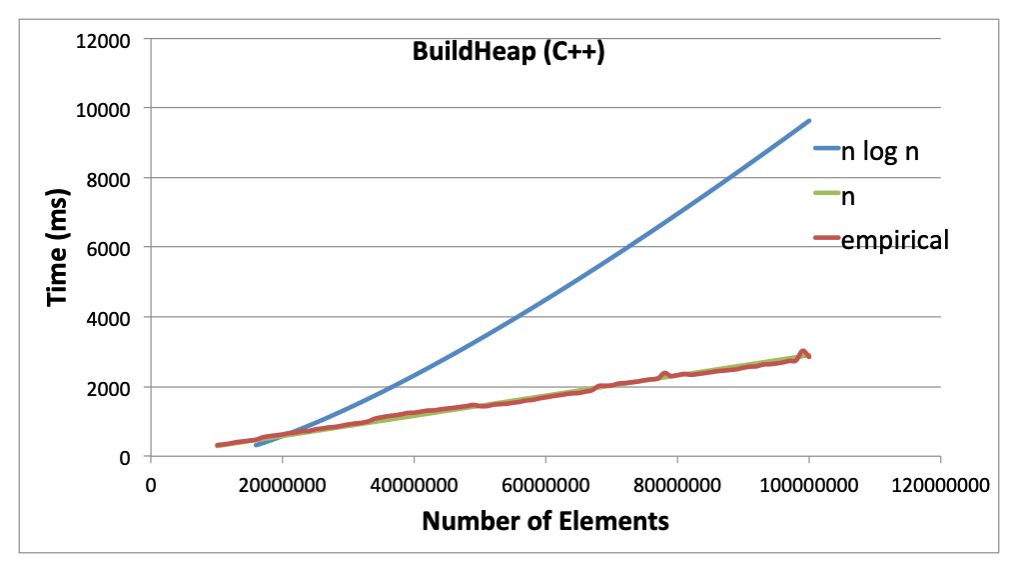

Building a heap from scratch

- What is the best method for building a heap from scratch (

buildHeap())- Let's say we wanted to create a heap from: 14, 9, 13, 43, 10, 8, 11, 22, 12

- We could insert each value in turn

- An insertion takes O(log n), and we have to insert n elements, so we would have a Big O of O(n log n)

- There is actually a better way!

- Insert all elements in the order they appear, without doing any bubbling.

- Starting from the lowest completely filled level at the right-most node with children (e.g., at position n/2 - 1), bubble down each element, going backwards in the array (also O(n) to heapify the whole tree). In other words:

for (int i = heapSize() / 2 - 1; i >= 0; i--) { bubbleDown(i); }

14

/ \

9 13

/ \ / \

43 10 8 11

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 12 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 14 | 9 | 13 | 43 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 22 | 12 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

- Start with the 43, which is at

heapSize() / 2 - 1(index 3)- Bubbling it down means that the 43 swaps with the 12:

14

/ \

9 13

/ \ / \

12 10 8 11

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 14 | 9 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

- Because we are looping backwards, the next index we look at is index 2, which holds the 13.

- Bubbling it down means that the 13 swaps with the 8:

14

/ \

9 8

/ \ / \

12 10 13 11

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 14 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

-

The next index we look at is 1, and the 9 does not need to be swapped, as it is already higher priority than its children.

-

Finally, we bubble-down the 14, which needs to first swap with the 8:

8

/ \

9 14

/ \ / \

12 10 13 11

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 8 | 9 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

- We must keep bubbling down the 14, swapping it with the 11:

8

/ \

9 11

/ \ / \

12 10 13 14

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

| values: | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 22 | 43 | ? | ? | ? |

| index: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

- Done!

- What is the complexity?

- Not trivial to determine, but it turns out to be O(n) (not bad!)

- Not trivial to determine, but it turns out to be O(n) (not bad!)