Binary Search Trees

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Autumn 2020, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturers: Chris Gregg and Julie Zelenski

Slide 2

Announcements

- The final assessment (project) guidelines have been posted

- Please start thinking of ideas for the personal project and talk to Chris, Julie, Chase or an SL by the end of the week.

- Assignment 6 is due on this Thursday and Assignment 7 will be released Thursday and due next Wednesday.

- We will not hold LaIR tomorrow in observance of U.S. Election Day, and office hours for Chase and Chris will be pushed to Wednesday and Thursday respectively.

Slide 3

Today's Topics

- Binary Search Trees (BSTs)

- Motivation

- Definition

- BST functions

findMin()findMax()contains(n)add(n)remove(n)

- Balanced binary search trees

Slide 4

Why the "binary search tree"

- Have you wondered how (and why) sets and maps in the Stanford Library (and the Standard library) have O(log n) behavior for searching?

- It is because those data structures are based on the balanced binary search tree that we will discuss today.

- The balanced binary search tree has logarithmic behavior for the operations we care about (insert, remove, find)

- BSTs enable O(n) behavior for retrieving elements in order (via an in-order traversal, discussed last time), too, so it is easy to retrieve the keys in order (thus, we say that we keep the keys in order).

- The bottom line: Binary Search Trees (BSTs) are great for set and map data structures.

Slide 5

Binary Search Tree Definition

- Binary trees are frequently used in searching.

- Binary Search Trees (BSTs) have an invariant that says the following:

- For every node, X, all the items in its left subtree are smaller than X, and the items in the right tree are larger than X.

- The following is a binary search tree:

6 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 8 ↙︎ ↘︎ 1 4 ↙︎ 3 -

Binary search trees (if built well – in other words balanced) have an average depth on the order of log(n): very nice!

- The following is not a binary search tree:

6 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 8 ↙︎ ↘︎ 1 4 ↙︎ ↘︎ 3 7 - Why? Because the 7 is in the left subtree of 6, and therefore out of place.

Slide 6

Binary Search Tree Functions

- In order to use binary search trees, we must define and write some functions for them (all can be recursive).

- We have four relatively easy functions to develop:

findMin()findMax()contains(n)add(n)

- We have one harder function to write:

remove()

- We will look at code for a

StringSetclass that implements these functions.

Slide 7

Easy functions: findMin() and findMax()

findMin()pseudocode:- Start at root, and go left until a node doesn't have a left child. That node is the minimum.

findMin()C++string StringSet::findMin() { return findMin(root); } string StringSet::findMin(Node *node) { // base cases if (node == nullptr) { return ""; // did not find } if (node->left == nullptr) { return node->str; } return findMin(node->left); }

findMax()pseudocode:- Start at root, and go right until a node doesn't have a right child. That node is the maximum.

findMax()C++string StringSet::findMax() { return findMax(root); } string StringSet::findMax(Node *node) { // base case if (node == nullptr) { return ""; // did not find } if (node->right == nullptr) { return node->str; } return findMax(node->right); }

Slide 8

Easy function: contains(s)

contains(s)pseudocode:- If the tree is empty, return false

- If the node we are at is x, return true

- Recursively call either

tree->leftortree->right, depending on x's relationship to the node (smaller or larger).

contains(s)C++:bool StringSet::contains(string s) { if (root == nullptr) { return false; } return contains(s, root); } // overloaded contains helper for recursion bool StringSet::contains(string &s, Node* node) { // base cases if (node == nullptr) { return false; } if (node->str == s) { return true; } // recursive cases if (s < node->str) { return contains(s,node->left); } else { return contains(s,node->right); } }

Slide 9

Easy function (but there are multiple ways to do it): add(x)

- This is similar to contains, because we first have to find where to put the value.

- One way to write the function would be to use some arms-length recursion: if we get to a node where the new node would to the left and the left is

nullptr, we can add the node as the left child. Likewise for the right child.- The only trouble with this method is that there is a special case when adding to an empty tree, but that is easy to take care of.

- It is also less compact than the next two solutions.

- Another way would be to use a reference to a pointer. This allows us to use regular recursion, and when we get to a

nullptr, we replace the pointer with a pointer to the new node. This works because we are really dealing with a reference to a pointer, so by changing the pointer, we are actually changing the original. - A third way would be to use a pointer to a pointer, or the infamous "double pointer". Much like a reference, we are passing around a pointer which has as its value the address of another pointer (the original), and when we update that other pointer's address, it changes the original.

add(x)pseudocode:- If the tree is empty, the new node becomes the root

- Recursively call either

tree->leftortree->right, depending on x's relationship to the node (smaller or larger). - If the node we have traversed to is

nullptr, add the node there

add(s)arms-length code:void StringSet::add(string s) { // call the arms-length add function if (root == nullptr) { root = new Node(s); count++; } else { addArmsLength(s, root); } } // overloaded add helper for recursion void StringSet::addArmsLength(string s, Node* node) { if (node->str > s) { if (node->left == nullptr) { node->left = new Node(s); count++; } else { addArmsLength(s, node->left); } } else if (node->str < s){ if (node->right == nullptr) { node->right = new Node(s); count++; } else { addArmsLength(s, node->right); } } }add(s)reference to pointer code:void StringSet::add(string s) { add(s, root); } void StringSet::add(string s, Node* &node) { if (node == nullptr) { node = new Node(s); count++; } else if (node->str > s) { add(s, node->left); } else if (node->str < s) { add(s, node->right); } }add(s)pointer-to-pointer code:void StringSet::add(string s) { add(s, &root); // need address of root pointer } void StringSet::add(string s, Node** node) { if (*node == nullptr) { *node = new Node(s); count++; } else if ((*node)->str > s) { add(s, &((*node)->left)); } else if ((*node)->str < s) { add(s, &((*node)->right)); } }

Slide 10

Hard function: remove(s)

6

↙︎ ↘︎

2 8

↙︎ ↘︎

1 5

↙︎

3

↘︎

4

- Removing a value from a binary search tree is relatively challenging

- There are several possibilities for how the node we want to remove is located in the tree:

- It could be a leaf. This is an easy case – we just remove the node from the tree. (e.g., remove 1 or 4 or 8 from the tree above)

- It could be a node that has only one child. This is also pretty easy – we just bypass the node as we might with a removal from a linked list. (e.g., remove 5 or 3 from the tree above)

- It could be a node with two children. Now, we have a challenge. (e.g., remove 2 or 6 from the tree above)

- We can't simply choose a child to promote, as that child could have two children (then what?), and we would also need to reconfigure so that we retain the BST invariant throughout (i.e., that each child has smaller elements to the left and bigger elements to the right).

- Instead, we need to find a node that can go where the one we are replacing is such that it won't change the BST invariant.

- There actually two choices:

- The smallest data in the right-most tree (e.g, if we are removing 2 in the tree above, we could replace the 2 with the 3)

- The largest data in the left-most tree (e.g., if we are removing the 2 in the tree above, we could replace the 2 with the 1)

- Why do these choices work?

- In both cases, the node we are choosing will always have either no children (e.g., 1) or only a single child (e.g., 3). Why? Because if it had two children, it wouldn't be the smallest in the right subtree or the largest in the left subtree!

- The actual algorithm is not too hard once you've worked out what to do (we'll use the smallest-of-the-right-subtree method):

- Replace the data in the node to remove with the data from the smallest element in the right subtree

- Remove the smallest element in the right subtree with one the appropriate method from above (it is either a leaf or has one child).

Slide 11

Have we created the perfect set?

- The average case Big O for our set based on a BST is as follows:

findMin(): O(log n)findMax(): O(log n)contains(s): O(log n)add(s): O(log n)remove(s): O(log n)

- This is great! But what about the worst case?

- What if we inserted the following elements in order into a BST?

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 - We would get the following:

1 ↘︎ 2 ↘︎ 3 ↘︎ 4 ↘︎ 5 ↘︎ 6 - Uh-oh. This is just a linked list. All of our nice functions are now O(n). ☹️

- What if we inserted the following elements in order into a BST?

- What we really want is a balanced tree (that is one nice thing about heaps: they are always balanced!)

Slide 12

Balancing Trees

- One possible idea for balancing a tree: require that the left and right subtrees in a BST have the same height.

- But…that can simply lead to this:

20 ↙︎ ↘︎ 18 33 ↙︎ ↘︎ 14 50 ↙︎ ↘︎ 7 61 ↙︎ ↘︎ 3 87 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 99 - This tree is balanced, but only at the root

Slide 13

Balancing Trees: left and right subtrees the same height?

- Another balance condition could be to insist that every node must have left and right subtrees of the same height: too rigid to be useful: it is not easy to continually change the tree to be in this form.

- If we relax the above standard a bit, we can get a reasonable balanced tree that can be kept balanced with some (relatively) simple operations.

- There are two common balanced binary search trees:

- The AVL tree: play around with an animation here.

- The Red/Black tree: play around with an animation here.

- The compromise we use for these trees is this: for every node, the height of the left and right subtrees can differ only by 1.

- The following is balanced. The tree to the left of 5 has a height of 3 and the tree to the right of 5 has a height of 2. Continuing, the tree to the left of 2 has a height of 1 and the tree to the right of 2 has a height of 2. The tree to the left of 8 has a height of 1, and the tree to the right of 8 (

nullptr) has a height of 0. There is never a subtree that differs in height by more than 1 from the corresponding subtree on the other side.5 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 8 ↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ 1 4 7 ↙︎ 3 - The following tree is not balanced. The tree to the left of 7 has a height of 3 and the tree to the right has a height of 1. They differ by more than 1.

7 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 8 ↙︎ ↘︎ 1 4 ↙︎ ↘︎ 3 5 - If you observe the behavior with the trees in the animations above, you can see rotations that happen when a tree becomes unbalanced. The actual rotation mechanics is beyond the scope of this class (but you will see it in CS 161).

- Specifically, there are actually four different types of insertions that can cause a node to become unbalanced. See here for a very good treatment of the AVL tree.

- Left-left: The insertion was in the left subtree of the left child of the unbalanced node.

- Right-right: The insertion was in the right subtree of the right child of the unbalanced node.

- Left-right: The insertion was in the right subtree of the left child of the unbalanced node.

- Right-left: The insertion was in the left subtree of the right child of the unbalanced node.

- For the first two insertions above (left-left and right-right), you need to perform a single rotation of the node.

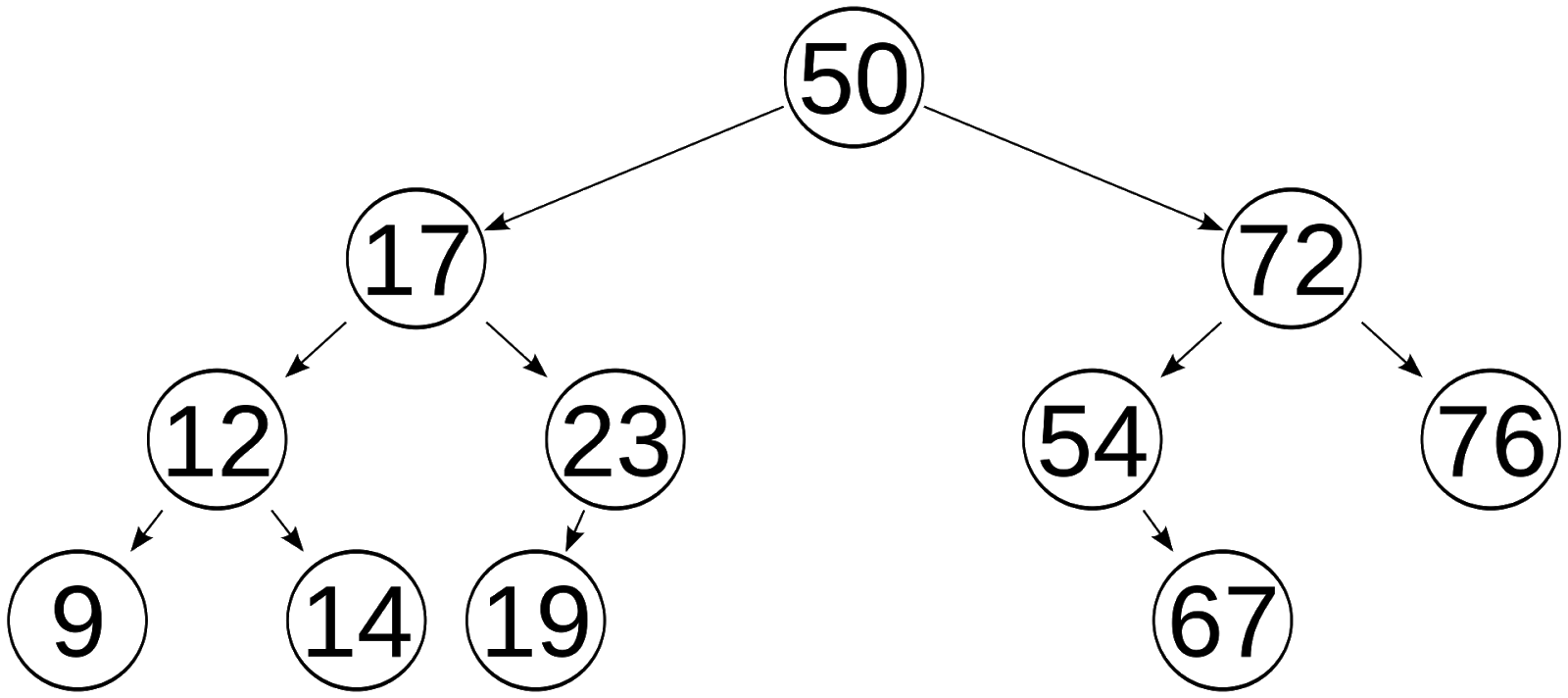

- To see a single rotation, insert 17, 12, 23, 9, 14, and 19 into an AVL tree. Then insert 18 and you'll see a single rotation.

- For the latter two insertions above (left-right and right-left), you need to perform a double rotation of the node.

- To see a double rotation, insert 20, 10, 30, 5, 25, 40, 35, and 45 into an AVL tree. Then insert 34. After that, if you add a 3, you will see another single rotation.

- To see lots of rotations, insert 30, 20, 10, 40, 50, 60, 70 into an AVL tree, and then insert 160, 150, 140, 130, 120, 110, 100, 80, 90.