Course Wrap-up and CS 107 Preview

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Autumn 2020, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturers: Chris Gregg and Julie Zelenski

Slide 2

Today's Topics

- Where we have been

- Where you are going

- Preview of CS107

Slide 3

Where we have been

- Assignment 1: Getting your C++ Legs

-

Soundex:

Digit represents the letters 0 A E I O U H W Y 1 B F P V 2 C G J K Q S X Z 3 D T 4 L 5 M N 6 R - Remember when you didn't know any C++? That wasn't that long ago!

- You've come a long way

- You now know a lot of C++ (but not all of it!)

- You've had plenty of practice with the debugger

- This can be a lifeline for almost any programming language, from Python to C++ to Javascript to Assembly Language

Slide 4

Where we have been

-

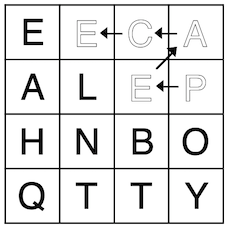

Assignment 2: Fun with collections

-

Maze:

- Search Engine:

Stand by while building index...

Indexed 50 pages containing 5595 unique terms.

Enter query sentence (RETURN/ENTER to quit): llama

Found 1 matching pages

{"http://cs106b.stanford.edu/assignments/assign2/searchengine.html"}

Enter query sentence (RETURN/ENTER to quit): suitable +kits

Found 2 matching pages

{"http://cs106b.stanford.edu/assignments/assign2/searchengine.html", "http://cs106b.stanford.edu/qt/troubleshooting.html"}

- We've learned about a lot of collections this quarter!

- Vectors and arrays

- Grids

- Sets

- Maps

- Stacks

- Queues

- Heaps and Priority Queues

- Linked Lists

- Trees

- Hash Tables

- Graphs

Slide 5

Where we have been

- Assignment 3: Recursion

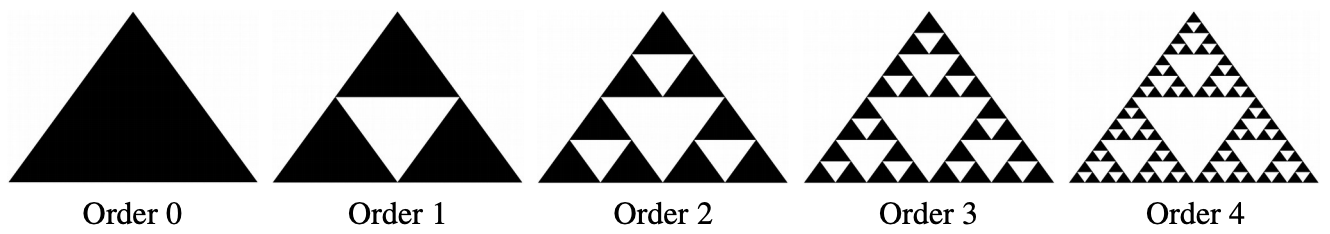

- Sierpinski:

- Recursion was a big part of this class

- You probably won't use recursion all that often in your own coding, but when you need it, it will come in very handy

Slide 6

Where we have been

-

Assignment 4: Backtracking

-

Boggle:

-

Banzhaf Power Index:

| Block | Block Count |

|---|---|

| Lions | 50 |

| Tigers | 49 |

| Bears | 1 |

- Recursion with backtracking can be super powerful for solving all sorts of counting problems, and problems where we need to do a large, coordinated search.

Slide 7

Where we have been

- Assignment 5: Priority Queue

8

/ \

9 11

/ \ / \

12 10 13 14

/ \ / \ / \ / \

22 43 __ __ __ __ __ __

- You built a couple of different priority queues, out of an array and out of a heap.

- This was also good practice building C++ classes

Slide 8

Where we have been

- Assignment 6: Linked Lists

- You started with a maze:

- You moved on to checking memory errors, and then to linked list sorts: more recursion!

Slide 9

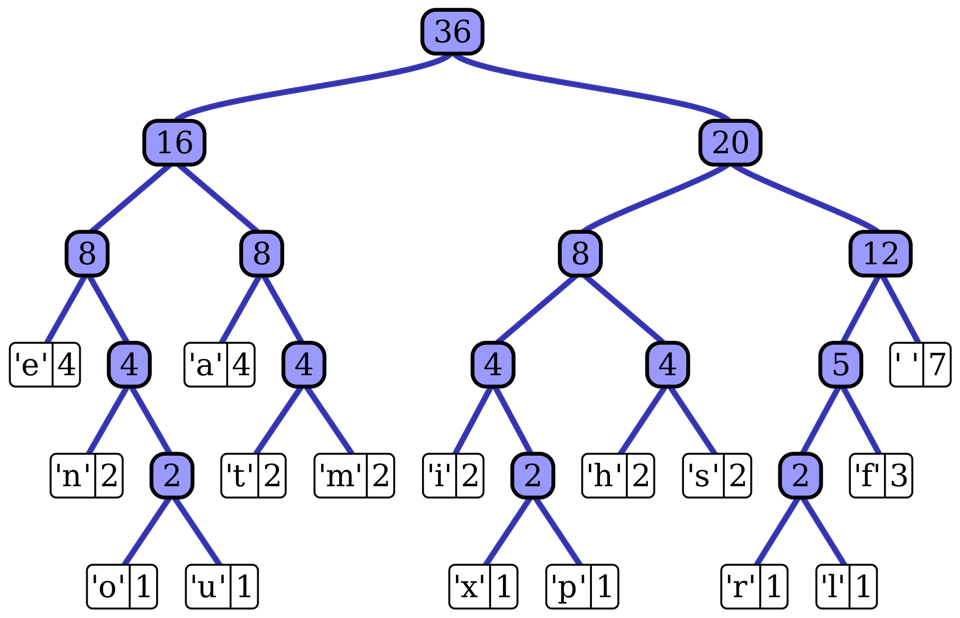

Where we have been

-

Assignment 7: Huffman

-

You finished up the quarter with some very cool Huffman coding to compress text.

Slide 10

I briefly showed you this program in the first lecture:

// Populate a Vector

// headers:

#include <iostream>

#include "console.h" // Stanford library

#include "vector.h" // Stanford library

using namespace std;

const int NUM_ELEMENTS = 100000;

// main

int main()

{

Vector<int> myList;

cout << "Populating a Vector with even integers less than "

<< (NUM_ELEMENTS * 2) << endl;

for (int i=0; i < NUM_ELEMENTS; i++){

myList.add(i*2);

}

for (int i : myList) {

cout << i << endl;

}

return 0;

}

Slide 11

The Importance of Data Structures

- One reason we care about data structures is, quite simply, time. Let’s say we have a program that does the following (and times the results):

- Creates four “list-like” containers for data.

- Adds 100,000 elements to each container – specifically, the even integers between 0 and 198,998 (sound familiar?).

- Searches for 100,000 elements (all integers 0-100,000)

- Attempts to delete 100,000 elements (integers from 0-100,000)

- What are the results?

Slide 12

The Importance of Data Structures

Computer Science is embarrassed by the computer.

– Alan Perlis

- Results:

- Processor: 2.7GHz Intel Core i7 (Macbook Pro), Compiler: clang++

- Compile options:

clang++ -Os -std=c++11 -Wall -Wextra ContainerTest.cpp -o ContainerTest

Structure Overall(s)

Unsorted Vector: 1.45973

Linked List: 8.17542

Binary Tree: 0.02734

Hash Table: 0.01316

Sorted Vector: 0.22202

- Difference between unsorted vector and hash table: 111x

- Difference between linked list and hash table: 621x!

- Note: In general, for this test, we used optimized library data structures (from the "standard template library") where appropriate. The Stanford libraries are not optimized.

- Overall, the Hash Table "won" — but (as we saw!) while this is generally a great data structure, there are trade-offs to using it.

Slide 13

The Importance of Data Structures

Structure Overall(s) Insert(s) Search(s) Delete(s)

Unsorted Vector: 1.45973 0.00045 0.92233 0.53694

Linked List: 8.17542 0.00688 5.92075 2.24779

Binary Tree: 0.02734 0.02415 0.00199 0.00120

Hash Table: 0.01316 0.01116 0.00088 0.00112

Sorted Vector: 0.22202 0.14747 0.00206 0.07248

- Why are there such discrepancies??

- Some structures carry more information simply because of their design.

- Manipulating structures takes time

Slide 14

Where to from here?

- The CS Core:

- Systems:

- CS 106B, Programming Abstractions

- CS 107, Computer Organization and Systems

- CS 110, Principles of Computer Systems

- Theory:

- CS 103, Mathematical Foundations of Computing

- CS 109, Introduction to Probability for Computer Scientists

- CS 161, Design and Analysis of Algorithms

- Systems:

Slide 15

CS 103

- CS 103, Mathematical Foundations of Computing is a good course to take early in your CS path

- Can computers solve all problems?

- Why are some problems harder than others?

- We can find in an unsorted array in O(n), and we can sort an unsorted array in O(n log n). Is sorting just inherently harder, or are there better O(n) sorting algorithms to be discovered?

- How can we be certain??

Slide 16

CS 107

- CS 107 is a typical follow-on course to CS 106B

- It is a classics systems class that covers many low-level topics

- How do we encode text, numbers, programs, etc., using just 0s an 1s?

- How are integers and doubles represented in memory?

- How do we manage the memory our programs use? What is the difference between the stack and the heap?

- What is assembly language and how does it work?

- CS 107 is not a litmus test for whether you can be a computer scientist

- You can be a great computer scientist wihout enjoying low-level systems programming (though some understanding can be helpful)

- CS 107 is not indicitive of what programming is "really like."

- CS 107 covers a lot of low-level programming. Most computer scientists don't regularly do low-level programming

Slide 17

How to Prepare for CS107

- You are prepared! CS106B is a great preparation!

- However, you might want to learn a few things before class

- The terminal

- You can log in to the

mythmachines right now with theterminalprogram (Mac/Linux) or on Windows with either the Windows subsystem for Linux, or with a downloadable terminal./afs/ir/users/c/g/cgregg/cowsay/bin/cowsay Moooo ls /afs/ir/users/c/g/cgregg/cowsay/share/cows /afs/ir/users/c/g/cgregg/cowsay/bin/cowsay -f stegosaurus rowr

- The terminal

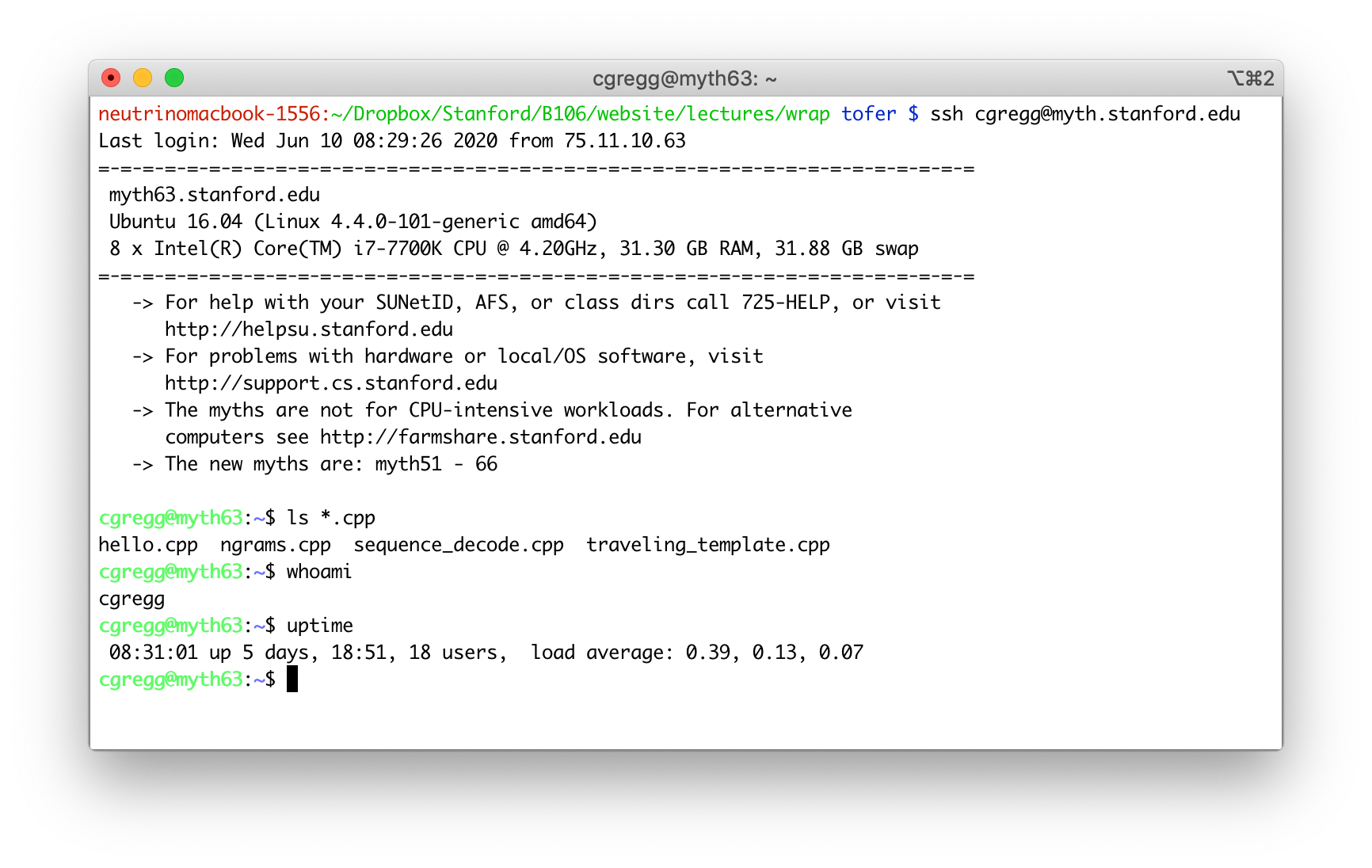

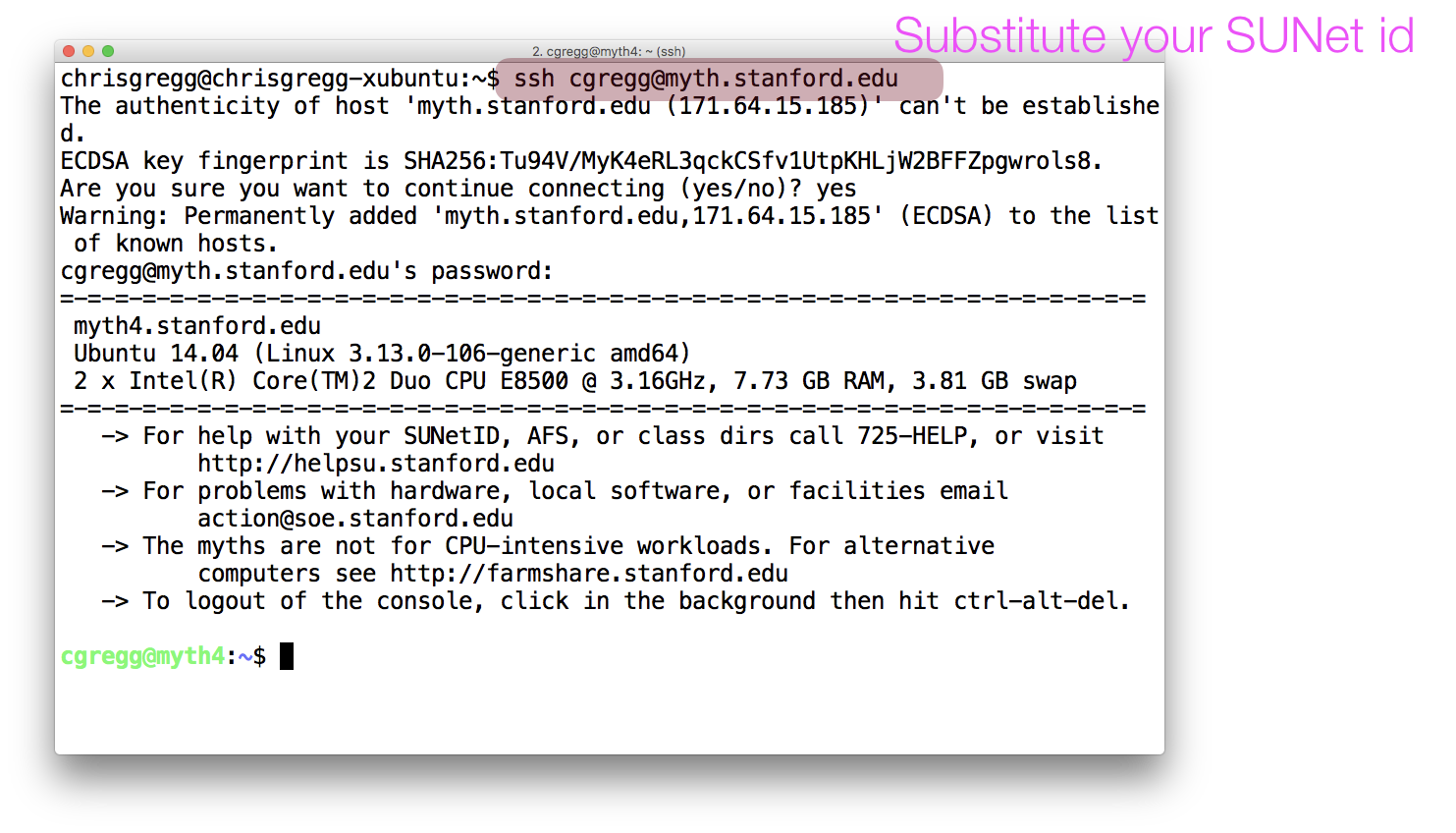

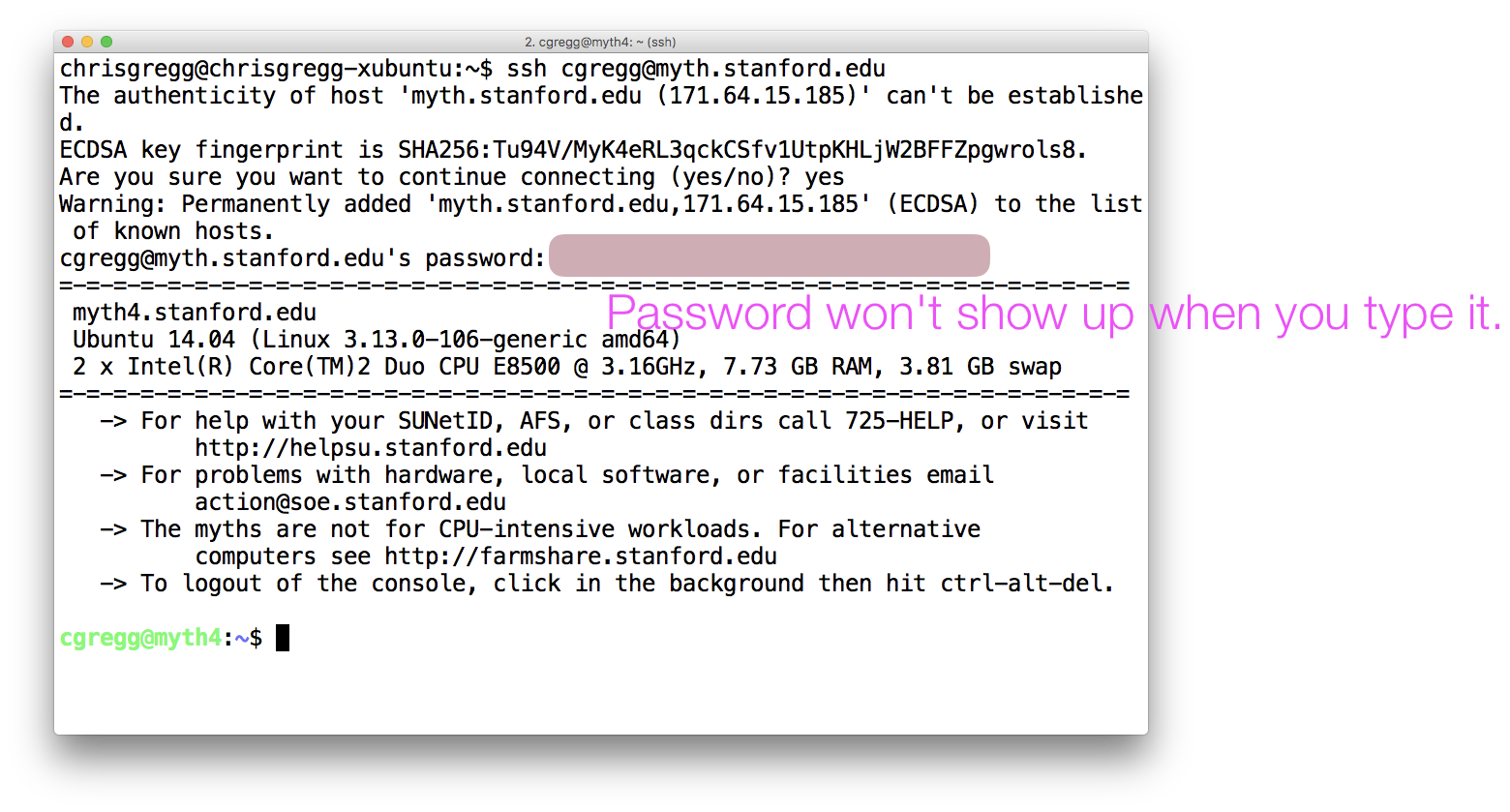

Slide 18

How to log into the myth machines

- Open Terminal. Then:

- You only need to answer the question about whether you want to continue connecting once:

- You type your SUNet password, but it doesn't show up for security reasons:

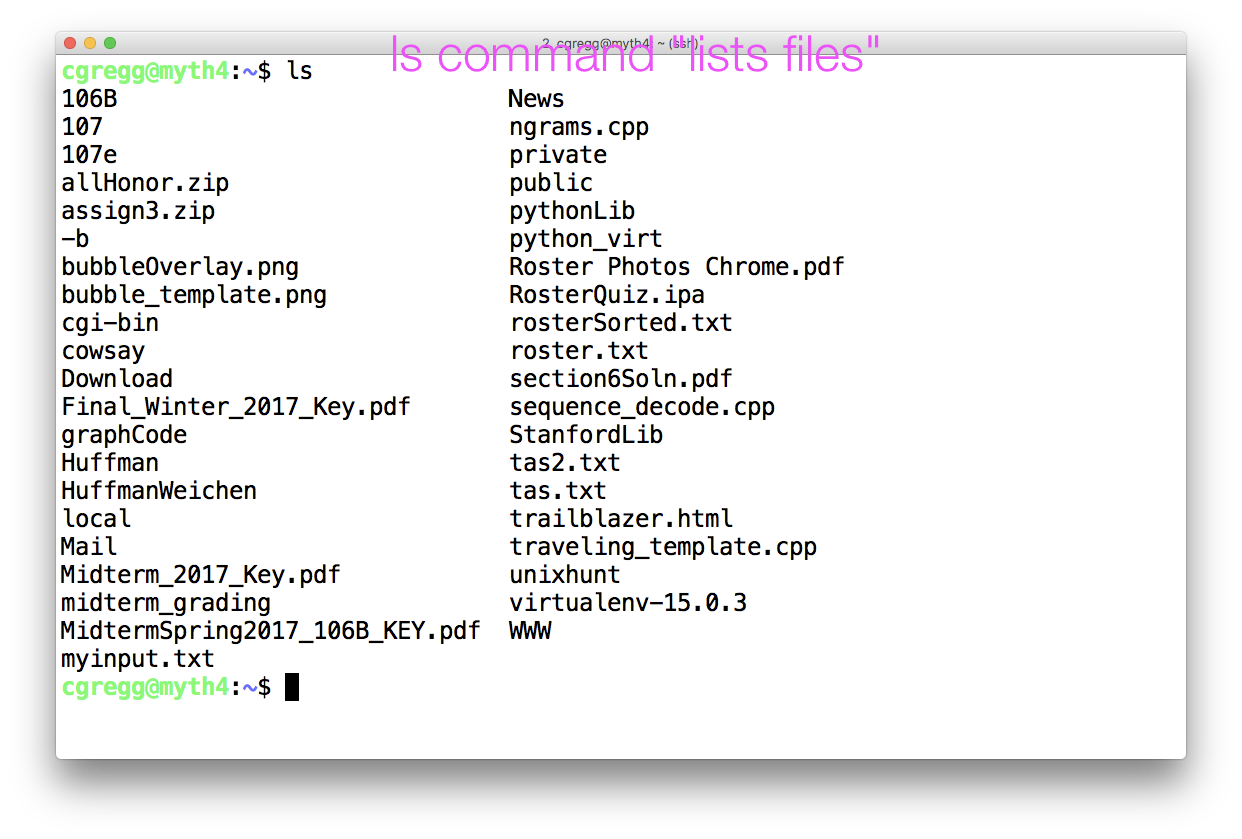

- The

lscommand lists the files:

- There are other commands, such as

whoamiandwhothat shows your SUNet and then everyone else logged into that particular machine.

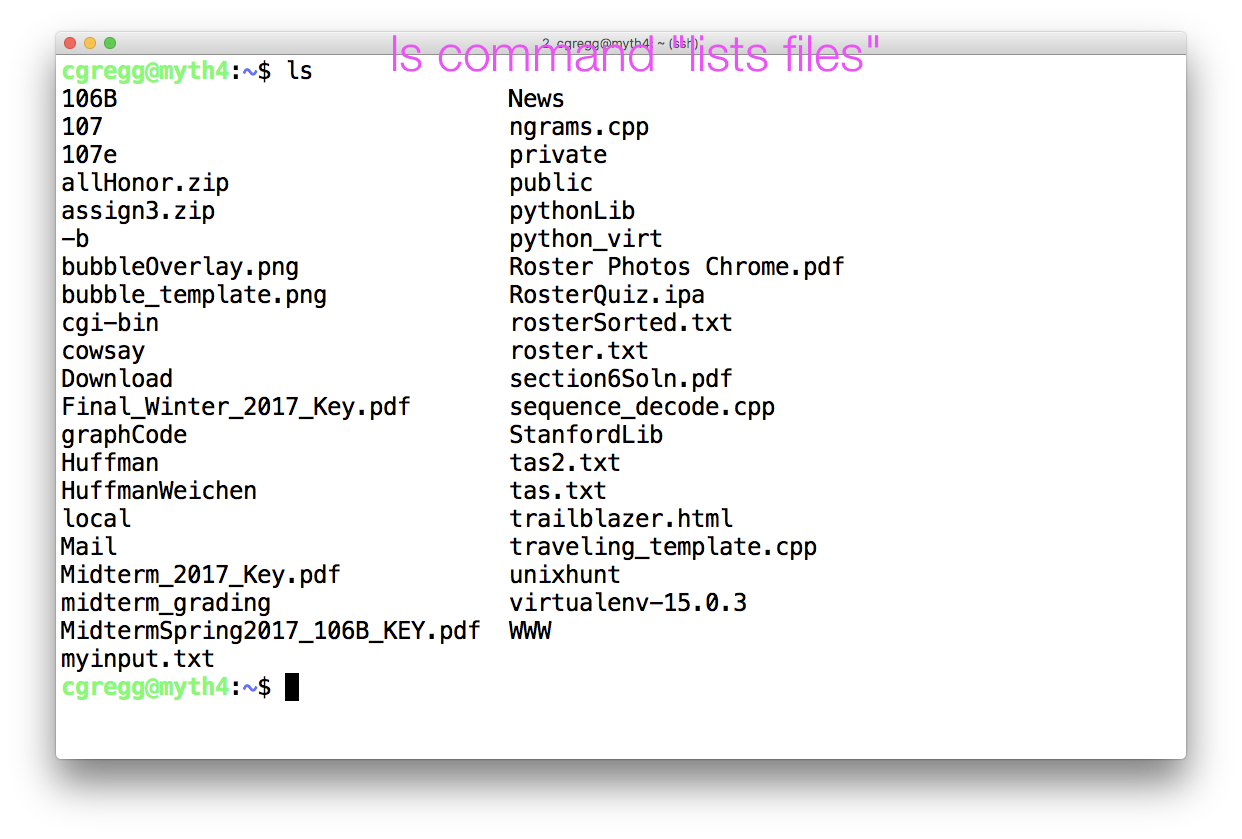

-

Your first

Cprogram!

- But, you probably want a real editor!

Slide 19

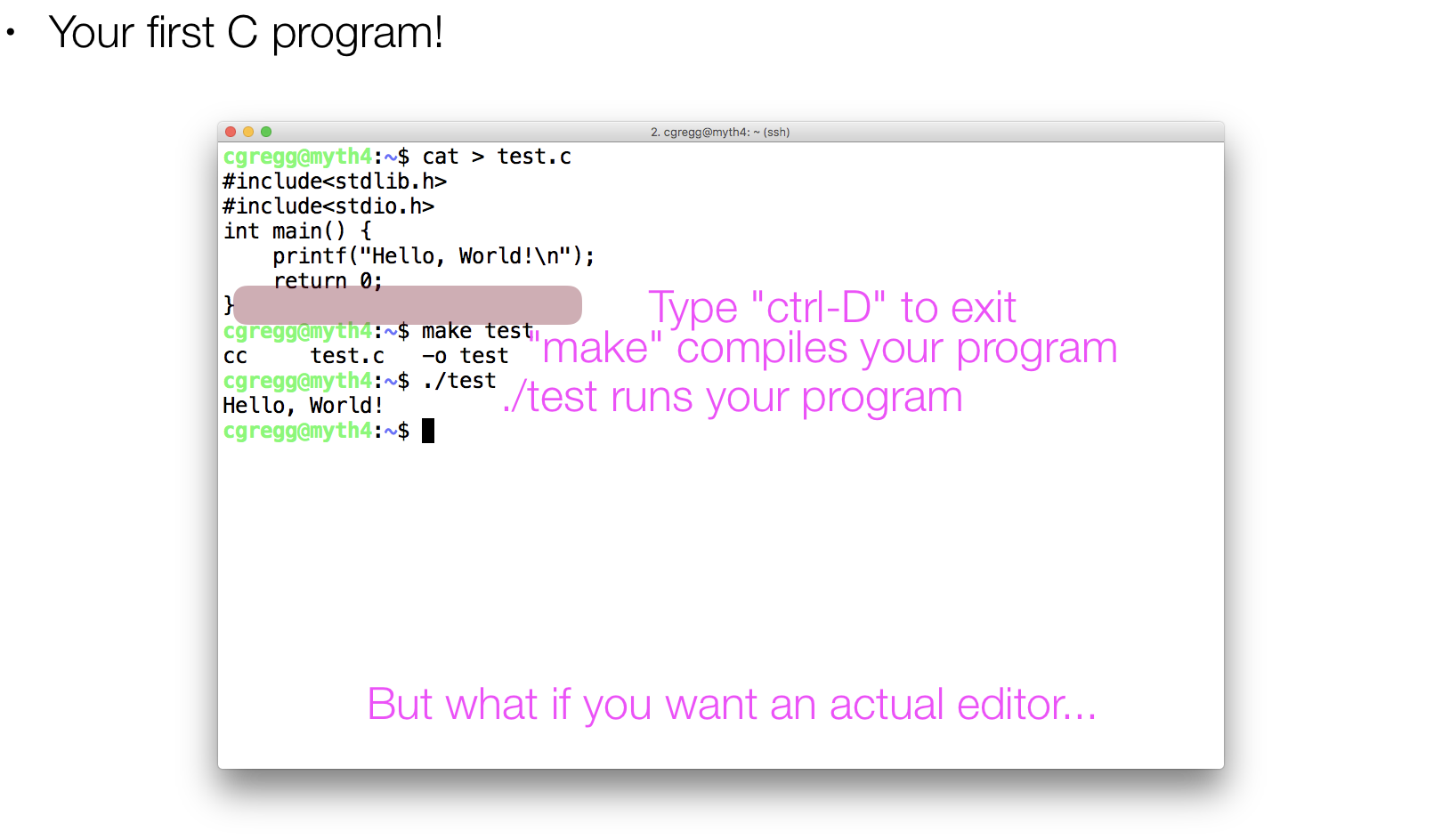

Editor Choices

- There are lots of choices for a terminal editor

- vi / vim

- emacs

- nano

- Sublime Text / Atom / VS Code from your own computer (slower, but you edit everything on your own computer)

- Choosing an editor can be a big choice…

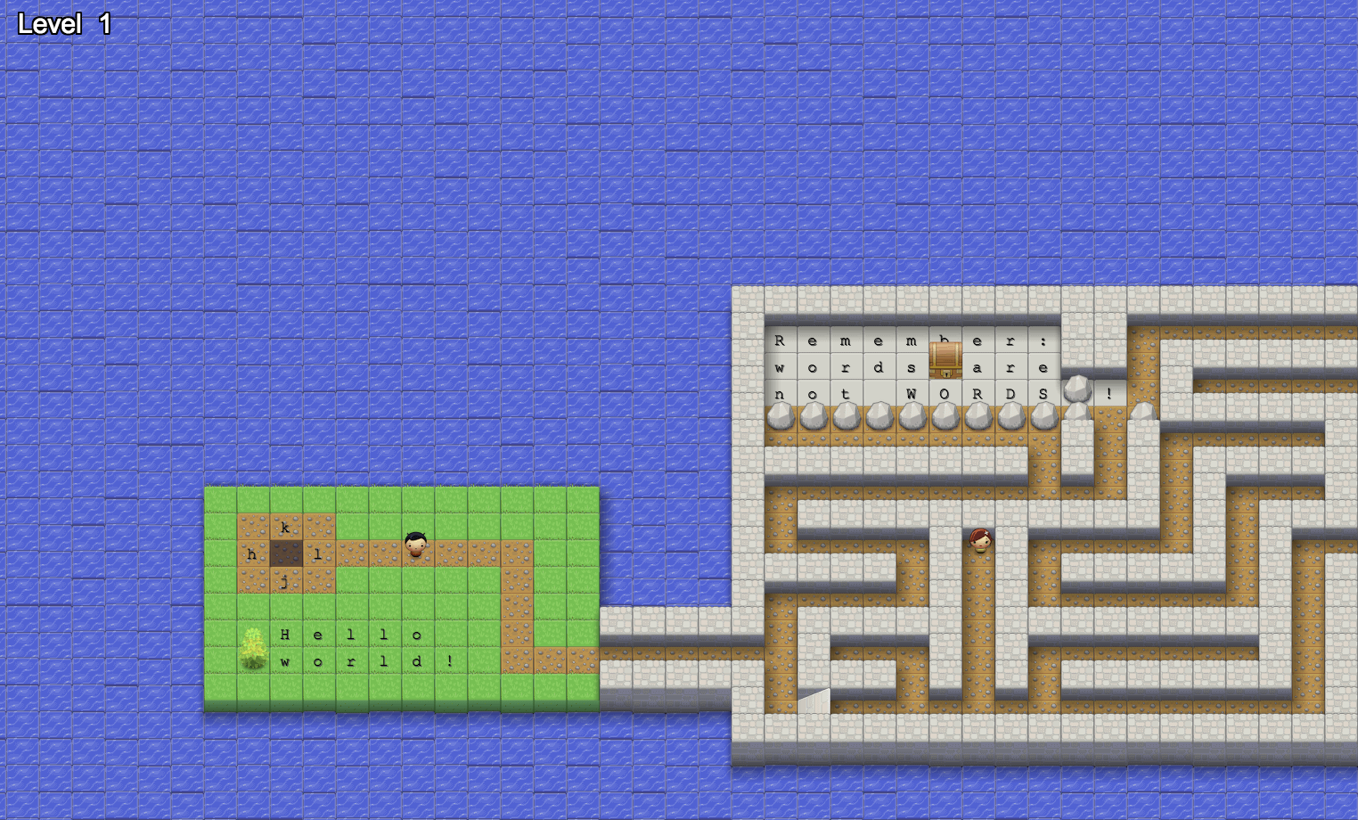

- If you want to learn how to use the

vimeditor, you can play Vim Adventures, which is a fun way to get up to speed.

Slide 20

How to prepare for CS107: Pointers

- Although we covered pointers in CS106B, you will really get to know them well in CS107. This is a good tutorial if you want to brush up.

- Pointer example – if you can understand this, you're in a good starting shape:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { int var; int* ptr; int** pptr; var = 3000; /* take the address of var */ ptr = &var; /* take the address of ptr using address of operator & */ pptr = &ptr; /* take the value using pptr */ printf("Value of var:\t%d\n", var ); printf("Value of ptr:\t%p\n", ptr); printf("Value of *ptr:\t%d\n", *ptr ); printf("Value of pptr:\t%p\n", pptr); printf("Value of *pptr:\t%p\n", *pptr); printf("Value of **pptr:\t%d\n", **pptr); return 0; } - output:

Value of var: 3000 Value of ptr: 0x7ffee662f728 Value of *ptr: 3000 Value of pptr: 0x7ffee662f720 Value of *pptr: 0x7ffee662f728 Value of **pptr: 3000

Slide 21

C / C++ Differences

- What is this

printfbusiness from the last slide?printf()is the way we print to the terminal in C. It is similar in function to C++'scoutbut it is a more standard function.

- Let's talk about some C / C++ differences:

- You will find C to be similar in feel to C++ (C++ is based on C, after all)

- Things that are the same:

- built-in data types:

int,char,float,double,long,unsigned int - array indexing (using brackets, e.g.,

v[4]) - function declarations

- modularity between

.hand.cfiles - control flow:

while,if,for, etc.

- built-in data types:

- Things that are different:

- There isn’t a

stringtype. Strings areNULLterminated arrays ofchars. - There are no classes, no objects, and no constructors/destructors.

- Memory management is more involved than in C++

- To allocate memory, C uses

malloc()(so can C++, but normally we usenew())

- To allocate memory, C uses

- There isn’t a

Slide 22

Going from C++ to C

- Things that are the same but that you might not have learned about yet:

- There are entities called “void pointers” which can point to any type

- You often need to cast variables to different types

- Pointer arithmetic is often used instead of bracket notation

Slide 23

From C++ to C

- C Strings are

NULLterminatedchararrays - There is no

stringclass in C. Let me repeat: there is nostringclass in C. - Strings are simply arrays of characters, with the final character of the array set aside for the

NULLcharacter, which is0. - You must be careful to avoid buffer overflows when dealing with

charstrings.

Slide 24

From C++ to C

malloc() and free(), and sizeof(): used for memory management instead of new and delete

malloc() is used to reserve memory from the heap. You must pass it the size in bytes of the amount of memory you want. How do you know the size in bytes? You use sizeof():

sizeof(int)returns the size of an integer. On our machines, this is 4 bytes, or 32-bits.malloc()returns a pointer to memory, e.g.,/* an array of 10 ints from the heap */ int *int_ptr; int_ptr = malloc(sizeof(int)*10);malloc()returnsNULLif the system runs out of memory.free()simply frees the previously allocated memory:/* an array of 10 ints from the heap */ int *int_ptr; int_ptr = malloc(sizeof(int)*10); free(int_ptr);

Slide 25

Pointer arithmetic

- Here is an example that uses pointer arithmetic:

#include<stdio.h> #include<stdlib.h> int main() { /* an array of 10 ints */ int *int_ptr; int_ptr = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int) * 10); int i; for (i = 0; i < 10; i++) { *(int_ptr + i) = i * 10; } for (i = 0; i < 5; i++) { printf("%d\n", *(int_ptr + i * 2)); // what will print out? We'd better look at printf } free(int_ptr); return 0; }

Slide 26

printf

printfis the way we print to standard out (stdout) in Cprintf()writes a formatted string to the standard output. The format can include format specifiers that begin with % and additional arguments are inserted into the string, replacing their formatters.- Example: print the

intvariable,i:int i = 22; printf("This is i: %d\n", i); - Output:

This is i: 22 printfhas lots of format specifiers (you will only use a few in CS 107):

| d or i | Signed decimal integer | 392 |

| u | Unsigned decimal integer | 7235 |

| o | Unsigned octal | 610 |

| x | Unsigned hexadecimal integer | 7fa |

| X | Unsigned hexadecimal integer (uppercase) | 7FA |

| f | Decimal floating point, lowercase | 392.65 |

| F | Decimal floating point, uppercase | 392.65 |

| e | Scientific notation (mantissa/exponent), lowercase | 3.9265e+2 |

| E | Scientific notation (mantissa/exponent), uppercase | 3.9265E+2 |

| g | Use the shortest representation: %e or %f | 392.65 |

| G | Use the shortest representation: %E or %F | 392.65 |

| a | Hexadecimal floating point, lowercase | -0xc.90fep-2 |

| A | Hexadecimal floating point, uppercase | -0XC.90FEP-2 |

| c | Character | a |

| s | String of characters | sample |

| p | Pointer address | b8000000 |

| n | Nothing printed. The corresponding argument must be a pointer to a signed int. The number of characters written so far is stored in the pointed location. |

|

| % | A % followed by another % character will write a single % to the stream. | % |

Slide 27

More printf examples

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf ("Characters: %c %c \n", 'a', 65);

printf ("Decimals: %d %ld\n", 1977, 650000L);

printf ("Preceding with blanks: %10d \n", 1977);

printf ("Preceding with zeros: %010d \n", 1977);

printf ("Radices: %d %x %o %#x %#o \n", 100, 100, 100, 100, 100);

printf ("floats: %4.2f %+.0e %E \n", 3.1416, 3.1416, 3.1416);

printf ("Width trick: %*d \n", 5, 10);

printf ("%s \n", "A string");

return 0;

}

Output:

Characters: a A

Decimals: 1977 650000

Preceding with blanks: 1977

Preceding with zeros: 0000001977

Radices: 100 64 144 0x64 0144

floats: 3.14 +3e+000 3.141600E+000

Width trick: 10

A string

Slide 28

Going from C++ to C (example from before)

- What does the following print out?

int main() { /* an array of 10 ints */ int *int_ptr; int_ptr = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int)*10); int i; for(i=0;i<10;i++) { *(int_ptr+i)=i*10; } for(i=0;i<5;i++) { printf("%d\n",*(int_ptr+i*2)); // what will print out? We'd better look at printf } free(int_ptr); return 0; } - Output:

0 20 40 60 80

Slide 29

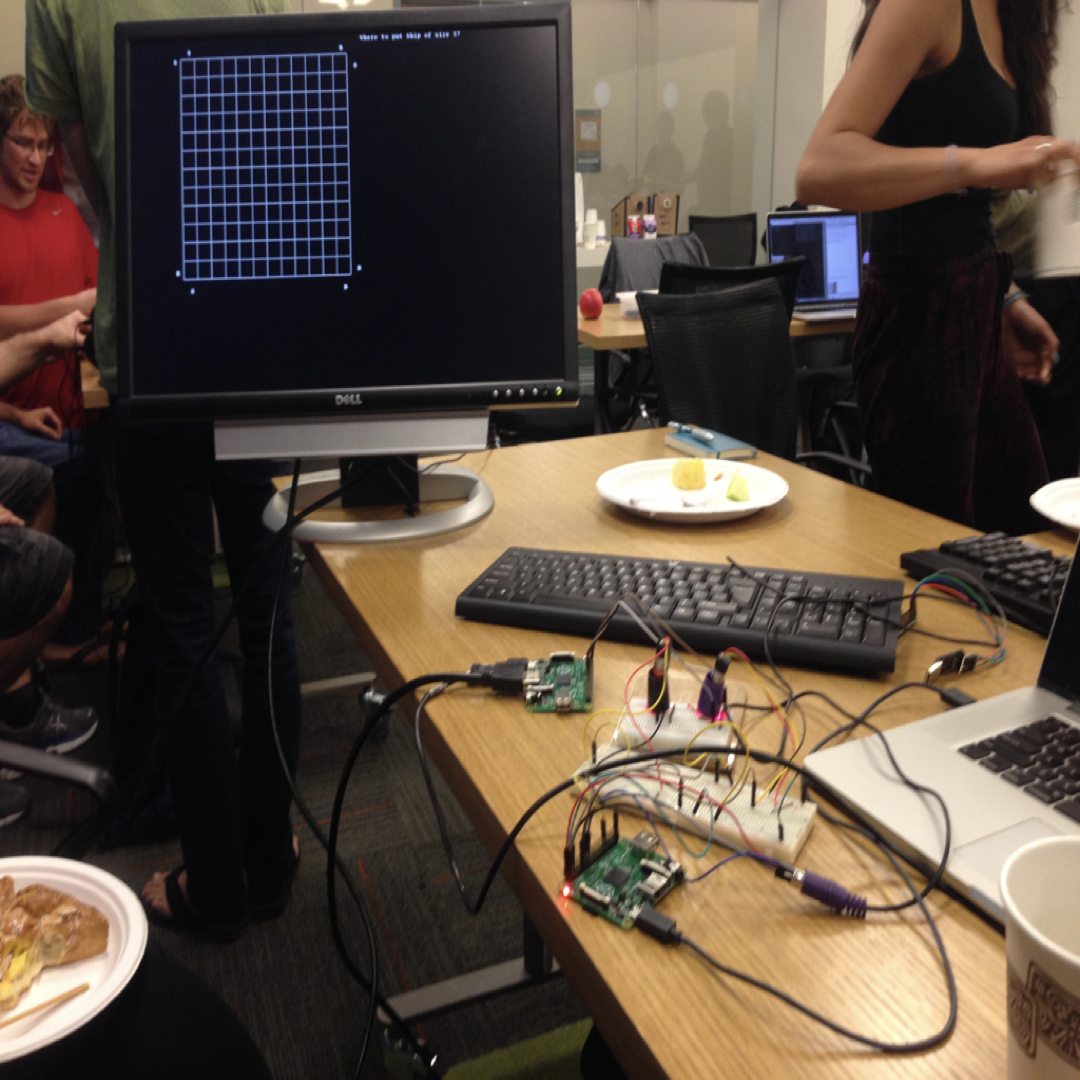

Other courses to consider taking: CS107e

- CS107e is an alternative to CS107, and it fulfills the requirements in the CS curriculum

- The class is a hands on version of the course, using bare metal (i.e., no operating system) Raspberry Pi computers.

- There is a lot of wiring, blinking lights, and a great final project that pushes you to build something unique and interesting.

Slide 30

Other courses to consider taking: CS109

- CS 109 is a probability class geared towards comptuer science majors

- It is narrative-driven, and also provides an introduction to machine learning.

Slide 31

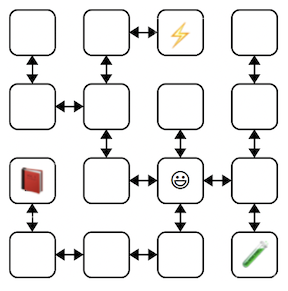

Computer Science Affects Every Field

- It is virtually impossible to name a field that hasn't benefitted from computer science in some way.

- Examples in the image above:

- Medicine

- Space

- Animation

- Self-driving technology

- Biomedical technology

Slide 32

Courses aren't necessary to continue your learning!

- Things to learn on your own:

- A new programming language. Good candidates:

- Javascript: the de facto standard on the World Wide Web

- Haskell – a great functional programming language. Functional programming is very different than procedural programming (which we have been learning), and it is eye-opening to code in a functional language. The best online resource: Learn You a Haskell for Great Good

- Swift – if you want to program for a Mac or iPhone

- Java – if you want o learn to program an Android phone (also, Kotlin, a newer language for Android phones)

- Python – if you didn't take CS 106A in Python, you should go learn Python right now. It is everywhere, and growing.

- iOS / Android Programming: learn to program your phone!

- Best iOS resource: https://www.raywenderlich.com

- Good tutorials link: http://equallysimple.com/best-android-development-video-tutorials/

- Want to code for all phones (and the web, and the desktop?) Check out React Native: https://facebook.github.io/react-native/

- Hardware: Raspberry Pi, Arduino, FPGA: Hardware is awesome!

- GPU and Multicore Programming: hard, but your code can fly

- Your GPU might have hundreds of individual processors. Resources

- A new programming language. Good candidates:

Slide 33

It is the time and place for computer science

Slide 34

Thank you!

- From all of the course staff: thank you for your hard work during this challenging

- Congratulations!