Section7: Trees

Section materials curated by our Head TA Trip Master,

drawing upon materials from previous quarters. Special thanks to

Nick Bowman

and Julie Zelenski for awesome ideas!

This week’s section exercises are all about trees, particularly binary search trees and common tree idioms and algorithms. Trees are yet another way to organize the way that data is stored and they are perhaps one of the most powerful paradigms for data storage that we've encountered so far! Their recursive structure makes writing recursive functions very natural, so we will be using lots of recursion when working with trees. After you're done working through this section handout, you'll truly know what it means to party with trees!

Remember that every week we will also be releasing a Qt Creator project containing starter code and testing infrastructure for that week's section problems. When a problem name is followed by the name of a .cpp file, that means you can practice writing the code for that problem in the named file of the Qt Creator project. Here is the zip of the section starter code:

For all the problems in this handout, assume the following structures have been declared:

struct TreeNode {

int data;

TreeNode *left;

TreeNode *right;

// default constructor does not initialize

TreeNode() {}

// 3-arg constructor sets fields from arguments

TreeNode(int d, TreeNode* l, TreeNode* r) {

data = d;

left = l;

right = r;

}

};

1) No, You're Out of Order!

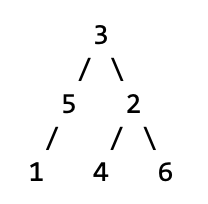

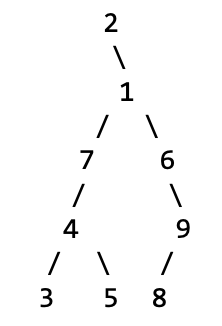

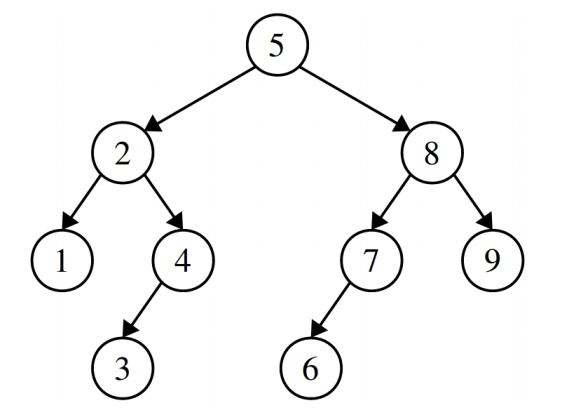

Write the elements of each tree below in the order they would be seen by a pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversal. Which of these three trees (if any) are a binary search tree? Is there anything about the results of the traversals that helped you make this identification?

a)

b)

c)

a.

pre-order: 3 5 1 2 4 6

in-order: 1 5 3 4 2 6

post-order: 1 5 4 6 2 3

b.

pre-order: 5 2 1 4 3 8 7 6 9

in-order: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

post-order: 1 3 4 2 6 7 9 8 5

c.

pre-order: 2 1 7 4 3 5 6 9 8

in-order: 2 3 4 5 7 1 6 8 9

post-order: 3 5 4 7 8 9 6 1 2

In this case, only the second tree is a binary search tree, since it's nodes maintain the property that all nodes to the left of any given node are less than it and all nodes to the right of any given node are greater than it. We can tell from the in-order traversal that it is a binary search tree because the numbers are printed out in order, which is a cool property of BSTs!

2) Binary Tree Insertion

Draw the binary search tree that would result from inserting the following elements in the given order.

Here's the alphabet in case you need it! ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

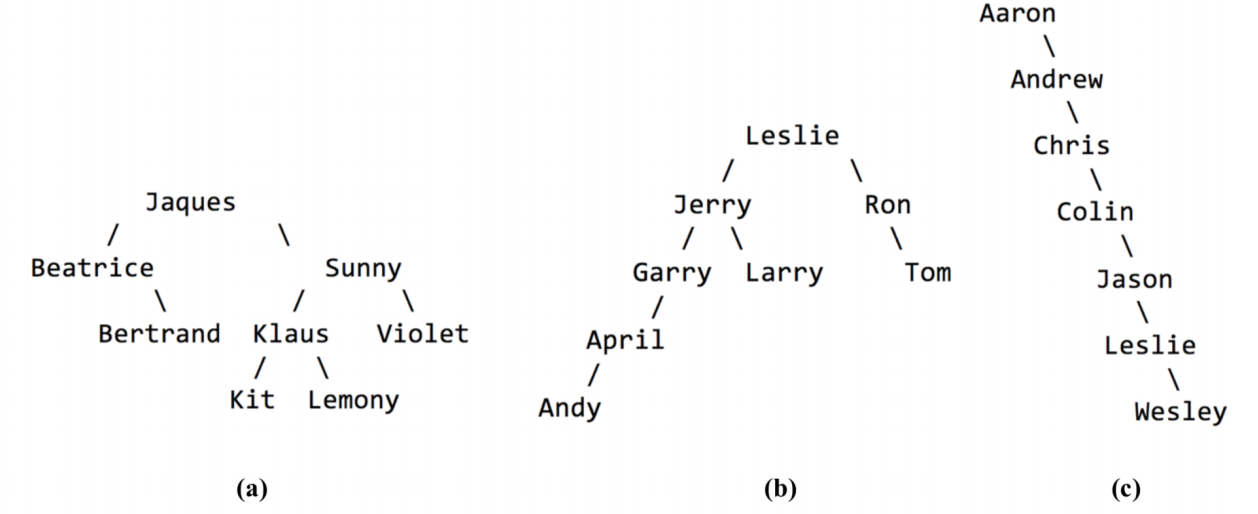

a. Jaques, Sunny, Klaus, Violet, Beatrice, Bertrand, Kit, Lemony

b. Leslie, Ron, Tom, Jerry, Larry, Garry, April, Andy

c. Aaron, Andrew, Chris, Colin, Jason, Leslie, Wesley

3) Binary Search Tree Warmup

Binary search trees have a ton of uses and fun properties. To get you warmed up with them, try working through the following problems.

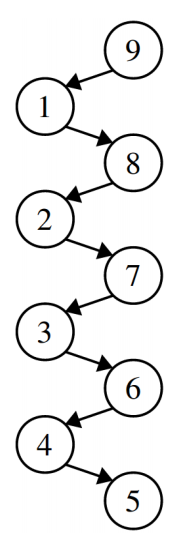

First, draw three different binary search trees made from the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. What are the heights of each of the trees you drew? What’s the tallest BST you can make from those numbers? How do you know it’s as tall as possible? What’s the shortest BST you can make from those numbers? How do you know it’s as short as possible?

Take one of your BSTs. Trace through the logic to insert the number 10 into that tree. Then insert 3.5.What do your trees look like?

There are several trees that are tied for the tallest possible binary search tree we can make from these numbers, one of which is shown to the right. It has height eight, since the height measures the number of links in the path from the root to the deepest leaf. We can see that this is the greatest height possible because there’s exactly one node at each level, and the height can only increase by adding in more levels. A fun math question to ponder over: how many different binary search trees made from these numbers have this height? And what’s the probability that if you choose a random order of the elements 1 through 9 to insert into a binary search tree that you come up with an ordering like this one?

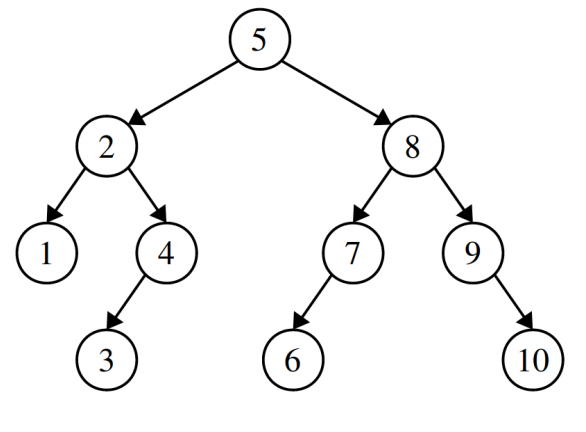

Similarly, there are several trees tied for the shortest possible binary search tree we can make from these numbers, one of which is shown below. It has height three, which is the smallest possible height we can have. One way to see this is to notice that each layer in the tree is, in a sense, as full as it can possibly be; there’s no room to move any of the elements from the deeper layers of the tree any higher up:

If we insert 10, we’d get the following:

4) Tree-Quality (equal.cpp)

Write a function

bool areEqual(TreeNode* one, TreeNode* two);

that take as input pointers to the roots of two binary trees (not necessarily binary search trees), then returns whether the two trees have the exact same shape and contents.

Let’s use the recursive definition of trees! The empty tree is only equal to the empty tree. A nonempty tree is only equal to another tree if that tree is nonempty, if the roots have the same values, and if the left and right subtrees of those roots are the same. That leads to this recursive algorithm:

bool areEqual(TreeNode* one, TreeNode* two) {

/* Base Case: If either tree is empty, they had both better be empty. */

if (one == nullptr || two == nullptr) {

return one == two; // At least one is null

}

/* We now know both trees are nonempty. Confirm the root values match and

* that the subtrees agree.

*/

return one->data == two->data

&& areEqual(one->left, two->left)

&& areEqual(one->right, two->right);

}

5) Count Left Nodes (countleft.cpp)

Write a function

int countLeftNodes(TreeNode *node)

that takes in the root of a tree of integers and returns the number of left children in the tree. A left child is a node that appears as the root of a left-hand subtree of another node. For example, the tree in problem 1(a) has 3 left children (the nodes containing 5, 1, and 4).

int countLeftNodes(TreeNode *node) {

if (node == nullptr) {

return 0;

} else if (node->left == nullptr) {

return countLeftNodes(node->right);

} else {

return 1 + countLeftNodes(node->left) + countLeftNodes(node->right);

}

}

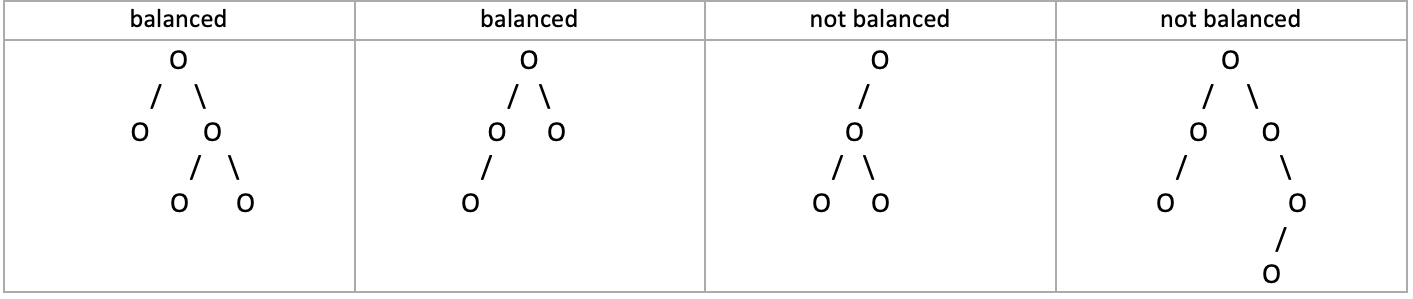

6) Find Your True Balance (balanced.cpp)

Write a function

bool isBalanced(TreeNode *node)

that takes in the root of a tree of integers and returns whether or not the tree is balanced. A tree is balanced if its left and right subtrees are balanced trees whose heights differ by at most 1. The empty tree is defined to be balanced. As a hint, feel free to implement a helper-version of problem 12 from section handout 6.

Using the height() function from last week's section handout:

bool isBalanced(TreeNode *node) {

if (node == nullptr) {

return true;

} else if (!isBalanced(node->left) || !isBalanced(node->right)) {

return false;

} else {

int leftHeight = height(node->left); // from problem 12 in section 6

int rightHeight = height(node->right);

return abs(leftHeight - rightHeight) <= 1;

}

}

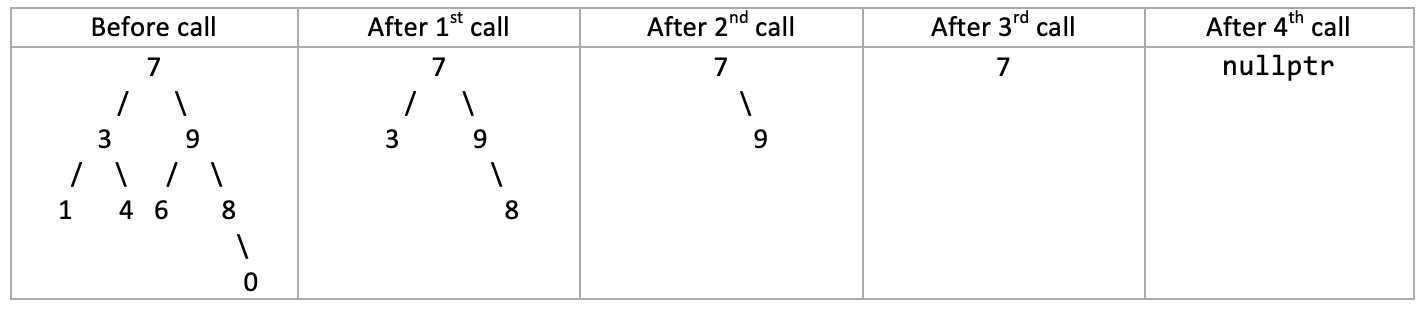

7) Give 'Em The Axe (prune.cpp)

Write a function

void removeLeaves(TreeNode*& node)

that accepts a reference to a pointer to a TreeNode and removes the leaf nodes from a tree. A leaf is a node that has empty left and right subtrees. If t is the tree on the left, removeLeaves(t) should remove the four leaves from the tree (the nodes with data 1, 4, 6, and 0). A second call would eliminate the two new leaves in the tree (the ones with data values 3 and 8). A third call would eliminate the one leaf with data value 9, and a fourth call would leave an empty tree because the previous tree was exactly one leaf node. If your function is called on an empty tree, it does not change the tree because there are no nodes of any kind (leaf or not). You must free the memory for any removed nodes.

void removeLeaves(TreeNode*& node) {

if (node != nullptr) {

if (node->left == nullptr && node->right == nullptr) {

delete node;

node = nullptr; // you can do this since node is passed by reference!

} else {

removeLeaves(node->left);

removeLeaves(node->right);

}

}

}

8) The Ultimate and Penultimate Values (findmax.cpp)

Write a function

TreeNode* biggestNodeIn(TreeNode* root)

that takes as input a pointer to the root of a (nonempty) binary search tree, then returns a pointer to the node containing the largest value in the BST. What is the runtime of your function if the tree is balanced? If it’s imbalanced? Then, write a function

TreeNode* secondBiggestNodeIn(TreeNode* root)

that takes as input a pointer to the root of a BST containing at least two nodes, then returns a pointer to the node containing the second-largest value in the BST. Then answer the same runtime questions posed in the first part of this problem.

We could solve this problem by writing a function that searches over the entire BST looking for the biggest value, but we can do a lot better than this! It turns out that the biggest value in a BST is always the one that you get to by starting at the root and walking to the right until it’s impossible to go any further. Here’s a recursive solution that shows off why this works:

TreeNode* biggestNodeIn(TreeNode* root) {

if (root == nullptr) error("Nothing to see here, folks.");

/* Base case: If the root of the tree has no right child, then the root node

* holds the largest value because everything else is smaller than it.

*/

if (root->right == nullptr) return root;

/* Otherwise, the largest value in the tree is bigger than the root, so it’s

* in the right subtree.

*/

return biggestNodeIn(root->right);

}

And, of course, we should do this iteratively as well, just for funzies:

TreeNode* biggestNodeIn(TreeNode* root) {

if (root == nullptr) {

error("Nothing to see here, folks.");

}

while (root->right != nullptr) {

root = root->right;

}

return root;

}

Getting the second-largest node is a bit trickier simply because there’s more places it can be. The good news is that it’s definitely going to be near the rightmost node – we just need to figure out exactly where.

There are two cases here. First, imagine that the rightmost node does not have a left child. In that case, the second-smallest value must be that node’s parent. Why? Well, its parent has a smaller value, and there are no values between the node and its parent in the tree (do you see why?) That means that the parent holds the second-smallest value. The other option is that the rightmost node does have a left child. The largest value in that subtree is then the second-largest value in the tree, since that’s the largest value smaller than the max. We can use this to write a nice iterative function for this problem that works by walking down the right spine of the tree (that’s the fancy term for the nodes you get by starting at the root and just walking right), tracking the current node and its parent node. Once we get to the largest node, we either go into its left subtree and take the largest value, or we return the parent, whichever is appropriate.

TreeNode* secondBiggestNodeIn(TreeNode* root) {

if (root == nullptr) {

error("Nothing to see here, folks.");

}

TreeNode* prev = nullptr;

TreeNode* curr = root;

while (curr->right != nullptr) {

prev = curr;

curr = curr->right;

}

if (curr->left == nullptr){

return prev;

} else {

return biggestNodeIn(curr->left);

}

}

Notice that all three of these functions work by walking down the tree, doing a constant amount of work at each node. This means that the runtime is O(h), where h is the height of the tree. In a balanced tree that’s O(log n) work, and in an imbalanced tree that’s O(n) work in the worst-case.

9) Checking BST Validity (bst.cpp)

You are given a pointer to a TreeNode that is the root of some type of binary tree. However, you are not sure whether or not it is a binary search tree. For example, you might get a tree that is a binary tree but not a binary search tree. Write a function

bool isBST(TreeNode* root)

that, given a pointer to the root of a tree, determines whether or not the tree is a legal binary search tree. You can assume that what you’re getting as input is actually a tree, so, for example, you won’t have a node that has multiple pointers into it, no node will point at itself, etc.

As a hint, think back to our recursive definition of what a binary search tree is. If you have a node in a binary tree, what properties must be true of its left and right subtrees for the overall tree to be a binary search tree? Consider writing a helper function that hands back all the relevant information you’ll need in order to answer this question.

There are a bunch of different ways that you could write this function. The one that we’ll use is based on recursive definition of a BST from lecture: a BST is either empty, or it’s a node x whose left subtree is a BST of values smaller than x and whose right subtree is a BST of values greater than x.

This solution works by walking down the tree, at each point keeping track of two pointers to nodes that delimit the range of values we need to stay within.

bool isBSTRec(TreeNode* root, TreeNode* lowerBound, TreeNode* upperBound) {

/* Base case: The empty tree is always valid.*/

if (root == nullptr) return true;

/* Otherwise, make sure this value is in the proper range. */

if (lowerBound != nullptr && root->data <= lowerBound->data) return false;

if (upperBound != nullptr && root->data >= upperBound->data) return false;

/* Okay! We're in range. So now we just need to confirm that the left and

* right subtrees are good as well. Notice how the range changes based on the

* introduction of this node.

*/

return isBSTRec(root->left, lowerBound, root)

&& isBSTRec(root->right, root, upperBound);

}

bool isBST(TreeNode* root) {

return isBSTRec(root, nullptr, nullptr);

}