1 Reaction rate constants

One key focus of the current work is to analyze and understand

the knowledge gaps in the foundational fuel chemistry for combustion. To this end, the analyses and recommendations

given here and discussions about our future work are perhaps more important than

the FFCM-1 reaction model itself.

In particular, optimization and uncertainty evaluation provide useful

guidance for future experimental and theoretical studies of specific reaction

kinetics and combustion responses.

In what follows, we shall discuss some of the key areas that need to be

strengthened in the coming years.

| CO + O2 = CO2 + O | (R31) |

| CH2 + H2 = H + CH3 | (R60) |

| CH2 + CH = C2H2 + H | (R67) |

| CH3 + CH = H + C2H3 | (R109) |

| CH3 + HCO = CH4 + CO | (R114) |

| HCCO + O2 = products (OH+2CO) | (R172) |

The thermal decomposition of ethylene

| C2H4 (+M) = H2CC + H2 (+M) | (R237) |

is still poorly modeled and understood from a theoretical perspective, which is required for proper extrapolation of the consistent fitting of available data.

A persistent topic concerns reaction product branching fractions, and their temperature dependences, especially in cases where one channel gives more reactive or chain branching products. Included in our basic needs list are reactions such as

| CH2 + O2 = products | (R61-65) |

| C2H3 + OH = products | (R201-203) |

| C2H3 + O2 = products | (R204-206) |

and related steps on the same potential surfaces. We note that reactions R204-206 have been studied very recently by Goldsmith et al. [1]. Their theoretical rates have not yet been implemented in the current model. The reaction between CH2 and O2 can be highly exothermic and have products that undergo non-equilibrium decomposition to present a chain branching scenario. Possible decreases in such rates at high pressures due to faster collisions also need to be investigated further. A recent trajectory study by Labbe et al [2,3] on the H + CH2O and OH + CH2O reactions suggests some HCO product molecules can are sufficiently excited to promptly dissociate. Such effects may extend to other exothermic reactions forming HCO or other weakly bound products, and will also be pressure dependent. The authors also show that such dissociative channels can have significant effects on computed flame speeds. Thus, this product branching issue presents another kinetic uncertainty. Note that the current optimization did result in an increase in the HCO dissociation rate constant (M = N2), which would be consistent with this effect.

Ketene (CH2CO), acetaldehyde (CH3CHO) and singlet methylene (CH2, ã1A1) kinetics are less well known than most, but of low sensitivity for the targets considered thus far.

An ongoing problem for the kinetics of recombination or decomposition reactions concerns the relative collisional efficiencies of different collider gases. These are often not measured and may vary with system and temperature. The reaction model needs good values for major fuel, product, and diluent gases. Efficiencies for water are hard to obtain and seem large and varying. The optimization often uses targets with different bath gases: the prevalence of Ar for shock tube ignition and species studies and of N2 in flame speed measurements (and mechanism end-use applications) being the prime examples. The extent to which the 2 data set types are reconciled by adjusting various relative efficiencies that lack prior restraint limits the ability of the optimization to use these diverse experiments to confine the rest of the kinetics. Some carefully-designed, low-pressure-limit, even old-fashioned, kinetics experiments for many relevant colliders are needed in our opinion.

Possibly important omitted kinetics also present an uncertainty challenge, and the main known current shortcoming at the low-temperature end of the model range is the lack of peroxide kinetics. Many CH3OO(H) and C2H5OO(H) reactions have received limited investigation. Extra HO2 reactions also require addition, particularly with ethylene to form oxirane (ethylene oxide), for which kinetics knowledge is also somewhat limited. We will add the oxirane and vinyl alcohol (C2H3OH) isomers to the next mechanism.

Other reactions whose rates are sizably altered by the optimization are

| CO + O (+M) = CO2 (+M) | (R30) |

| HCO (+N2) = H + CO (+N2) | (R35-M=N2) |

| HO2 + CH2O = HCO + H2O2 | (R91) |

The spin-forbidden reaction (R30) impacts the laminar flame speed of certain high-pressure syngas mixtures (e.g., fls_26b and more notably fls_37a). In the initial rate compilation, high and low-pressure rate constant expressions were taken from Troe [4] with Lindemann falloff. Low-pressure limit rates were based on analysis of CO2 decomposition data, and the high-pressure value is an estimate. Recent theoretical calculations [5] indicate a substantially faster high-pressure rate, by a factor of 9 to 27 from 1000 to 2500 K. The recombination requires a spin-changing switch of electronic state potential energy surfaces, whose probability is difficult to determine. When the initial trial model was tested against the flame speed data of 40-atm, (95% CO+5% H2)/(O2+7 He) syngas mixtures [6], it over-predicted the flame speeds by as much as a factor of 2 for equivalence ratios > 2.5 (see the target sheet for fls_37a). The flame speed value at φ = 3 was selected as a target. Optimization increased the high-pressure rate coefficient a factor of 10, in line with the theoretical result of Jasper et al. [5]. We did not, however, see a decrease in its range of uncertainty, which remains a factor of 10. Moreover, the optimized high-pressure limit rate constant and the original low-pressure rate constant place the rate coefficient in the fall-off regime under the conditions relevant to syngas combustion at around 50 bar. Thus, a better understanding of both the low-pressure limit rates and pressure falloff should strengthen the prediction accuracy of high-pressure syngas combustion.

The increase in the third body efficiency in HCO dissociation (R35) is driven by better prediction of the laminar flame speed of methane. Such change is perhaps consistent with the proposed direct dissociation of hot HCO from the reactions of CH2O + H and CH2O + OH, as discussed before, though this is not directly implied by the optimization.

For the reaction

| H + O2 (+M) = HO2 (+M) | (R15) |

the low-pressure limit rate and the collision efficiencies of H2O, Ar and He (relative to N2) of the trial model were taken from Burke et al. [7] (see the trial model page). A more recent study by Verdicchio et al. [8] used trajectory calculation and two-dimensional master equation methods to give a first principle prediction for the pressure-dependent rate constant for this reaction. The optimized low-pressure rate for M = Ar is smaller than the 2-D master equation result by a factor of 2, whereas the optimization produced a low-pressure rate for M = H2O that is a factor of 2 higher than the corresponding theoretical results. Although the difference can be the result of theoretical inaccuracy, we believe that the target experiments what impact k15 are equally, if not uncertain. Analysis of the optimization results show that the smaller rate for M = Ar is mainly driven by the high-pressure shock tube target measurements of Petersen et al. [9] (stm-1a, stm-2b & stm-3a), which are subject to uncertainty from the significant effect of small initial impurities [10]; and the increase for M = H2O is caused by a number of laminar flame speed targets (e.g., fls_9b and fls_10b), all of which have fairly large uncertainties. Nonetheless, it would be beneficial to obtain a more precise measurement for k15, ideally to within 20% uncertainty, for M = N2, H2O, Ar and He.

Optimization also altered k31 and k60 by large factors (a factor of ~2 for both).

| CO + O2 = CO2 + O | (R31) |

| CH2 + H2 = H + CH3 | (R60) |

The change of k31 is driven by the ignition delay of CO-H2-O2-Ar mixtures (ign_3a and ign_3b) [11]. These ignition delay targets are rather old, and in addition to R31, the target values are impacted by the rate coefficient of reaction R3:

| O + H2 = H + OH | (R3) |

Currently, the uncertainty factor of k3 is 1.6. The model predictive accuracy can be benefited by theory or experiment leading to a smaller uncertainty span in k3. Additional shock tube experiments for mixtures similar to ign_3a and ign_3b could lead to joint constraints for k3 and k31.

The change in k60 is driven largely by the time history data of the methyl radical in shock tube oxidation of methane (e.g., pro4a). This change may differ in the future, as it may be related to our adoption of the rate coefficient of reaction

| CH3 + H (+M) = CH4 (+M) | (R97) |

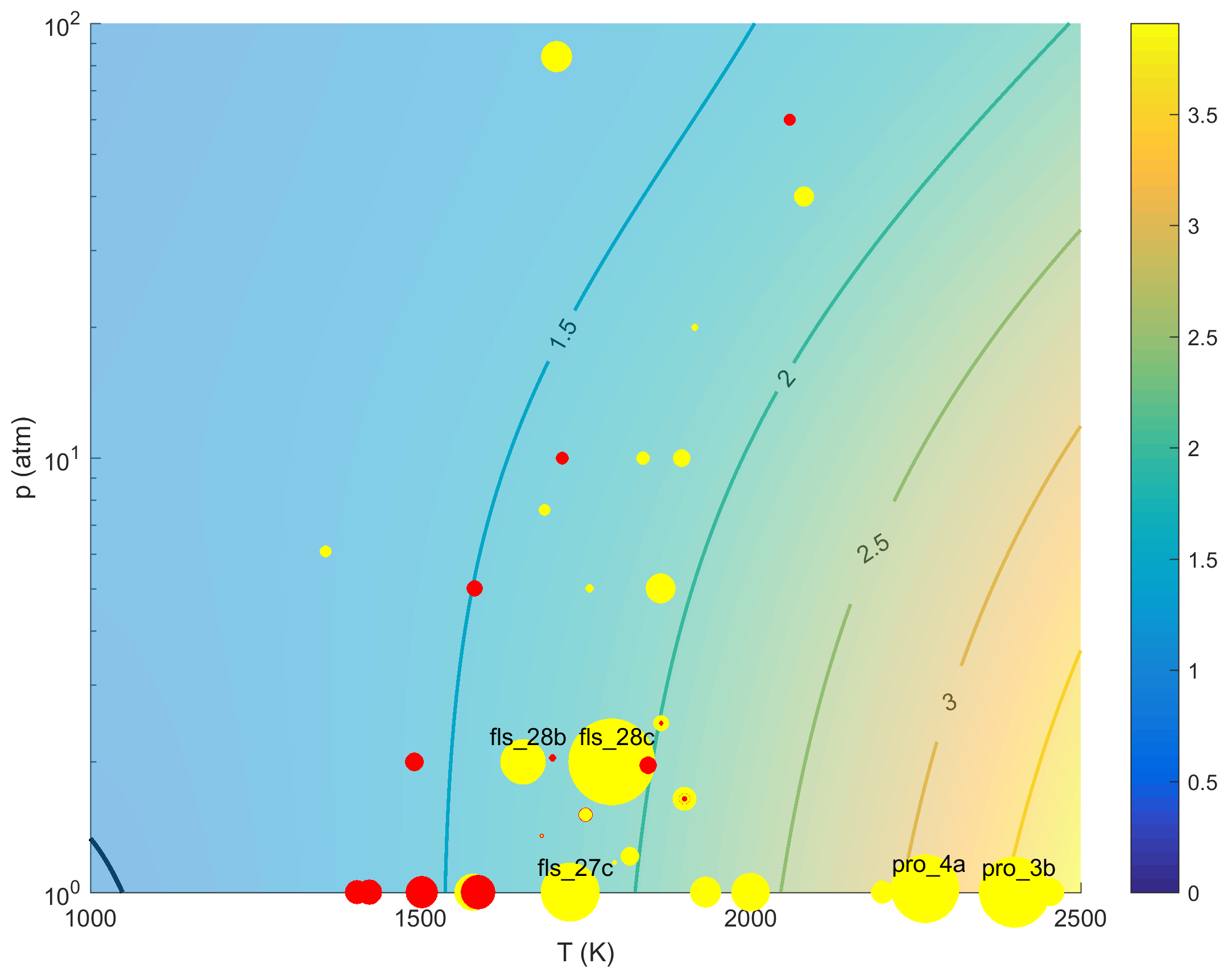

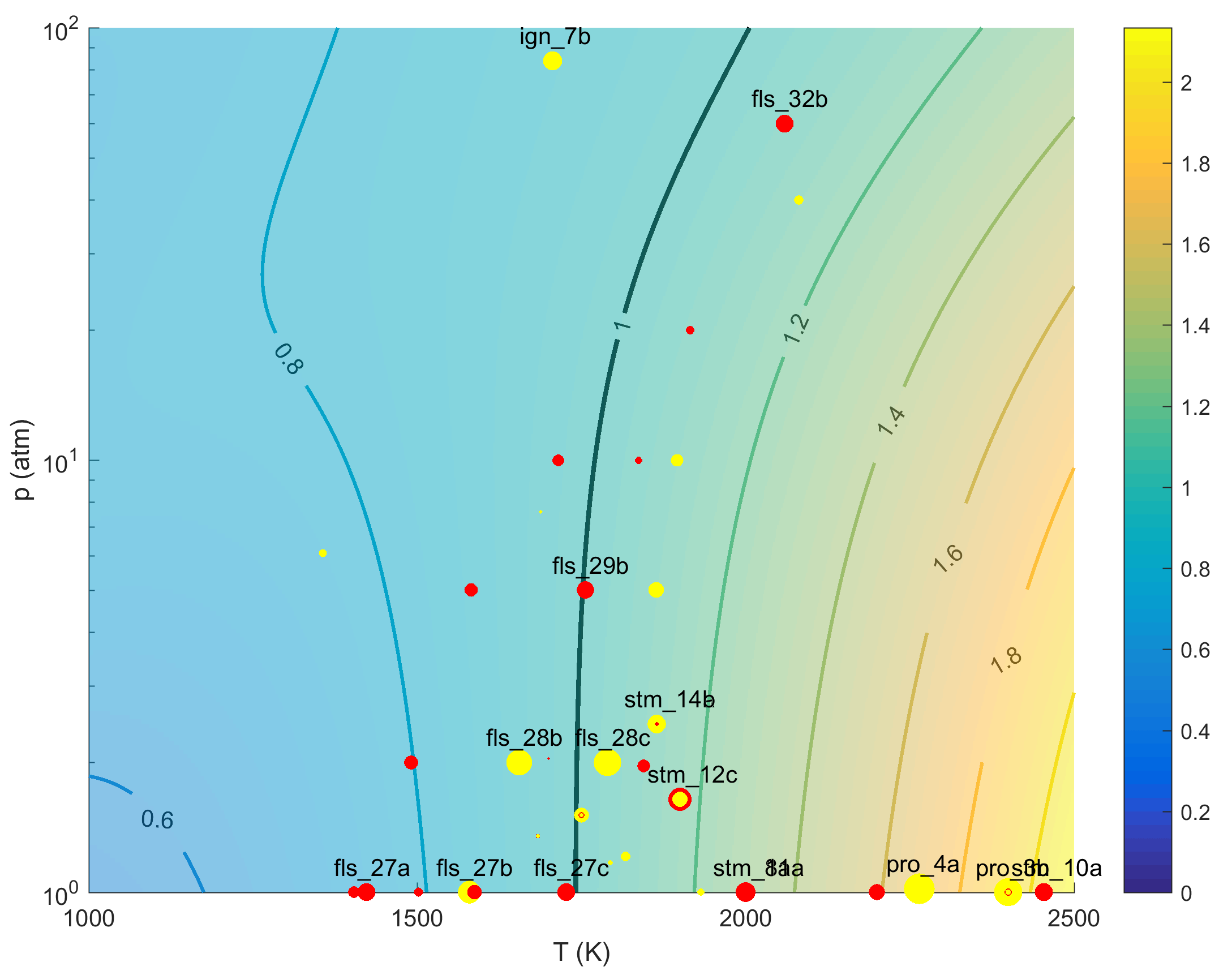

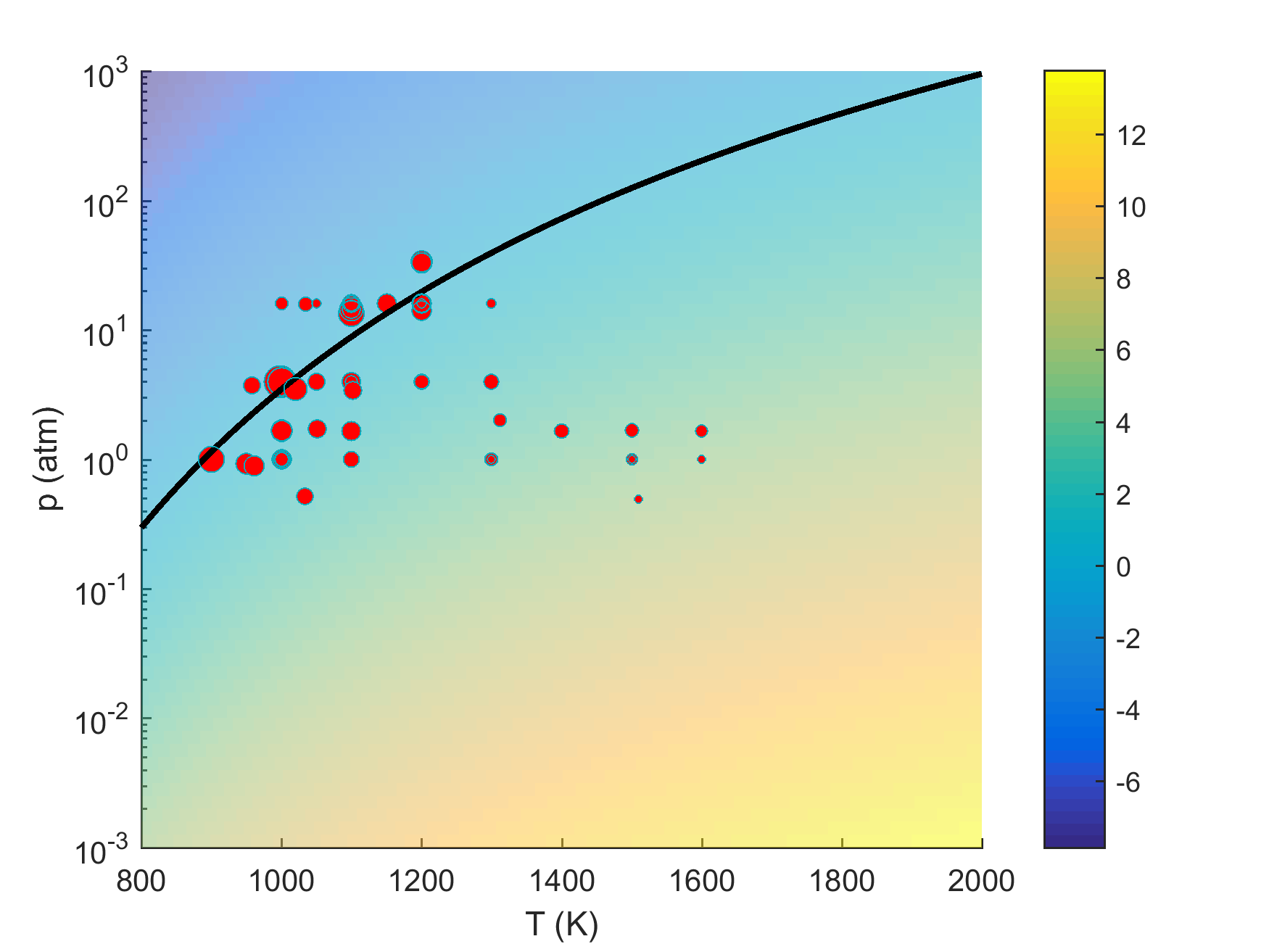

from an earlier study by Golden [12]. Optimization reduced k97 by ~40%, which is in line with the more recent theoretical results of both Troe [13] and Golden [14] under conditions of the driving targets, as shown in Fig. 1. The fact that the target (p, T) conditions cluster around the isogram of 1:1 ratio between the optimized rate constant and the theoretical rate of Troe [13] indicates that the targets drive k97 preferentially towards rate values that are consistent with the recent theoretical values.

Other reactions whose rates have sizable changes from optimization are:

| CH3 + CH3 = H+C2H5 | (R113) |

| CH3 + H2= CH4 + H | (R136) |

| CH3 + H = CH2 + H2 | (R60) |

The validity of these changes will need to be examined after we update the rate coefficient of R97 to that from the more recent studies.

Figure 1. Color images expressing the ratio of trial (top panel) and optimized (bottom panel) rate coefficient of reaction R97 to the theoretical value of Troe [13] over the temperature range of 1000 to 2500 K, pressure from 1 to 100 atm and M = Ar. The Black, solid line represents unity rate ratio line, i.e., the (p, T) isogram on which the optimized rate value is equal to Troe's k(p, T) value. The red symbols indicate that the target value pushes up the rate value, while the yellow symbols indicate that the target value pushes down the rate value. The symbol size represents the level of driving force of the target, defined as derivative of the target term in the least squares objective function with respect to the normalized rate constant of R97. For the flame speed, the temperature value plotted is equal to the temperature at which the rate of R97 is the maximum in the flame. The fact that before optimization (the top panel) the (p, T) conditions of the targets are far removed from the unity ratio line, and after optimization (the bottom panel) the conditions of the targets cluster around the unity ratio line indicate that the consensus effect of the relevant targets forces the optimization of k97 in a manner that agrees better with Troe's theoretical value.

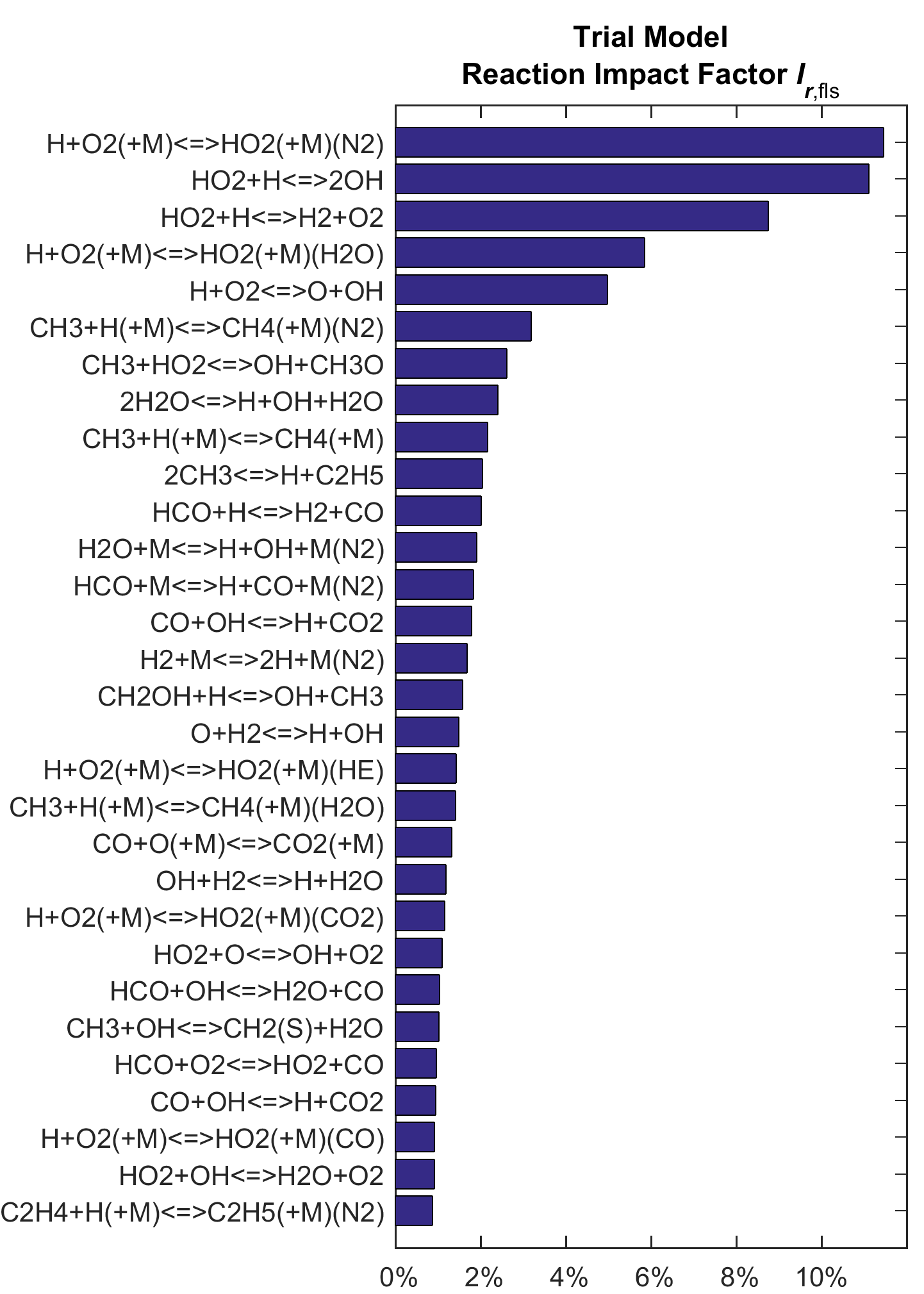

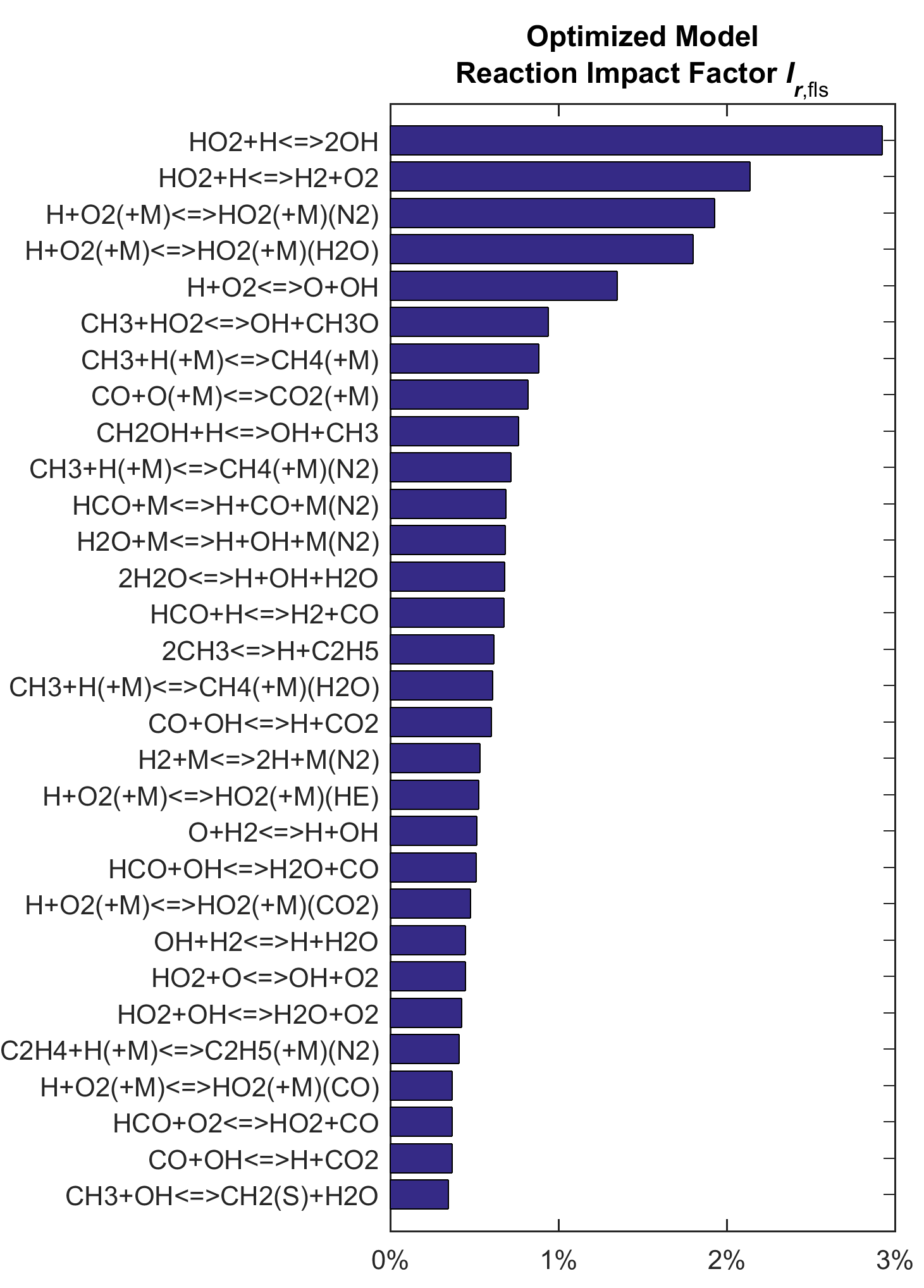

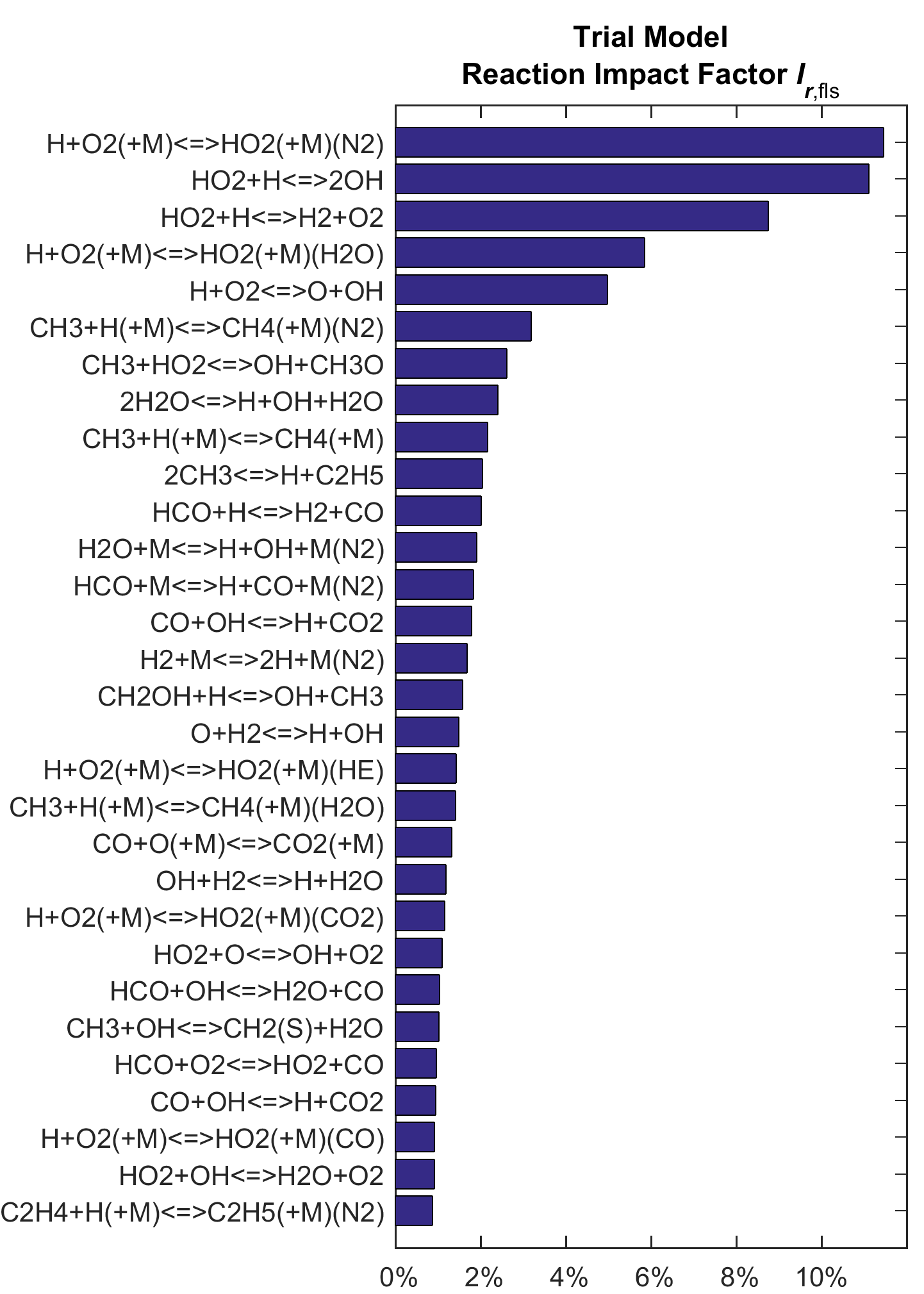

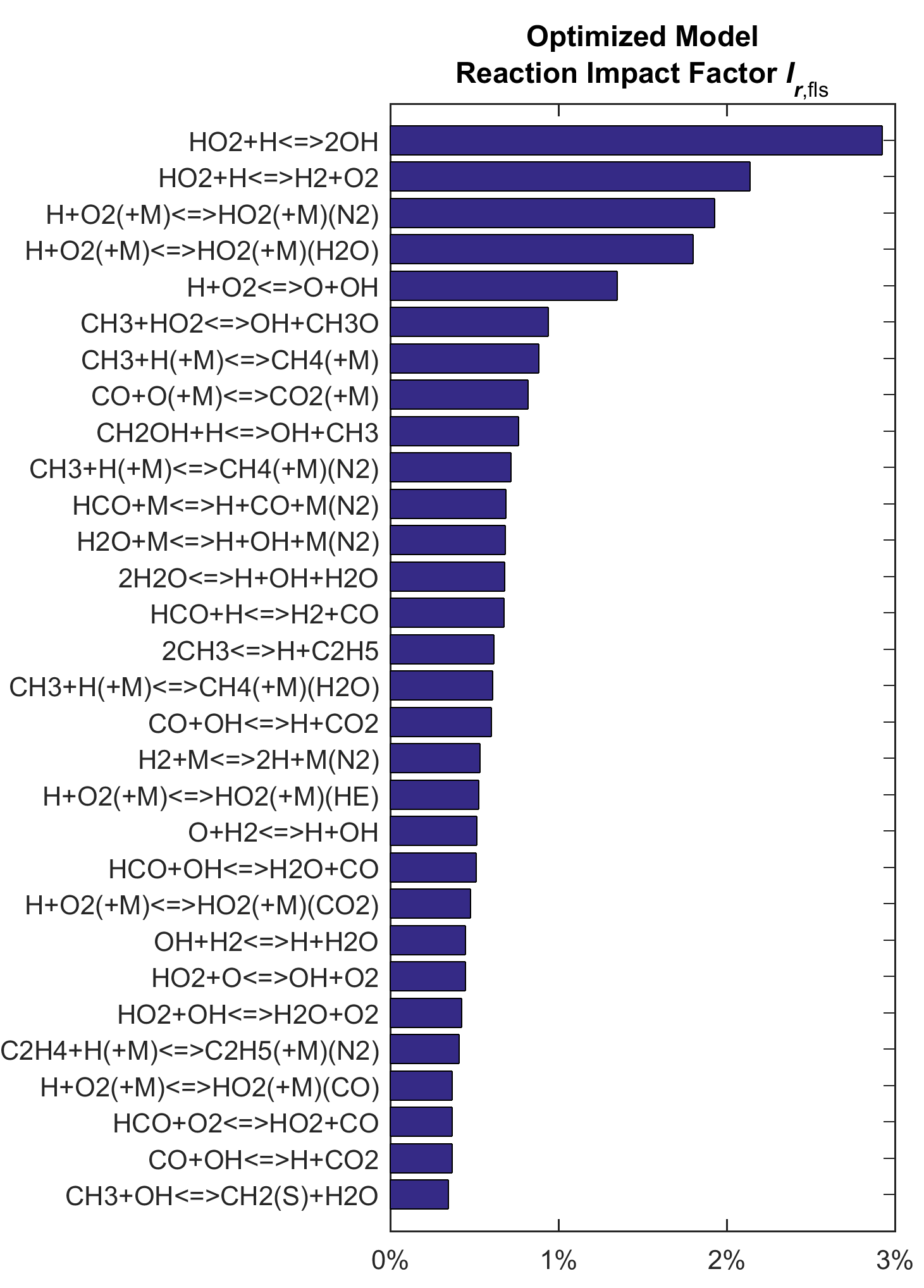

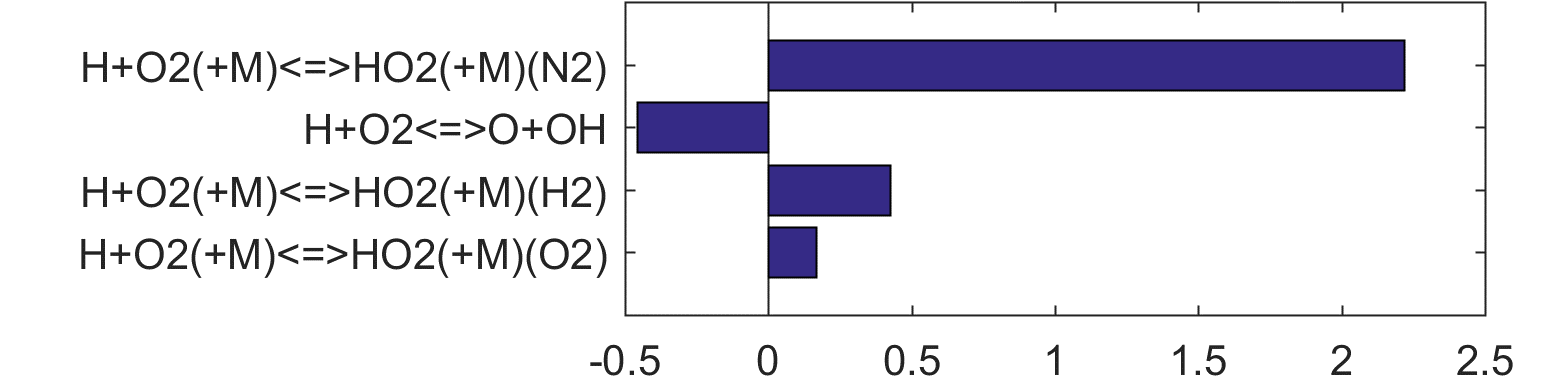

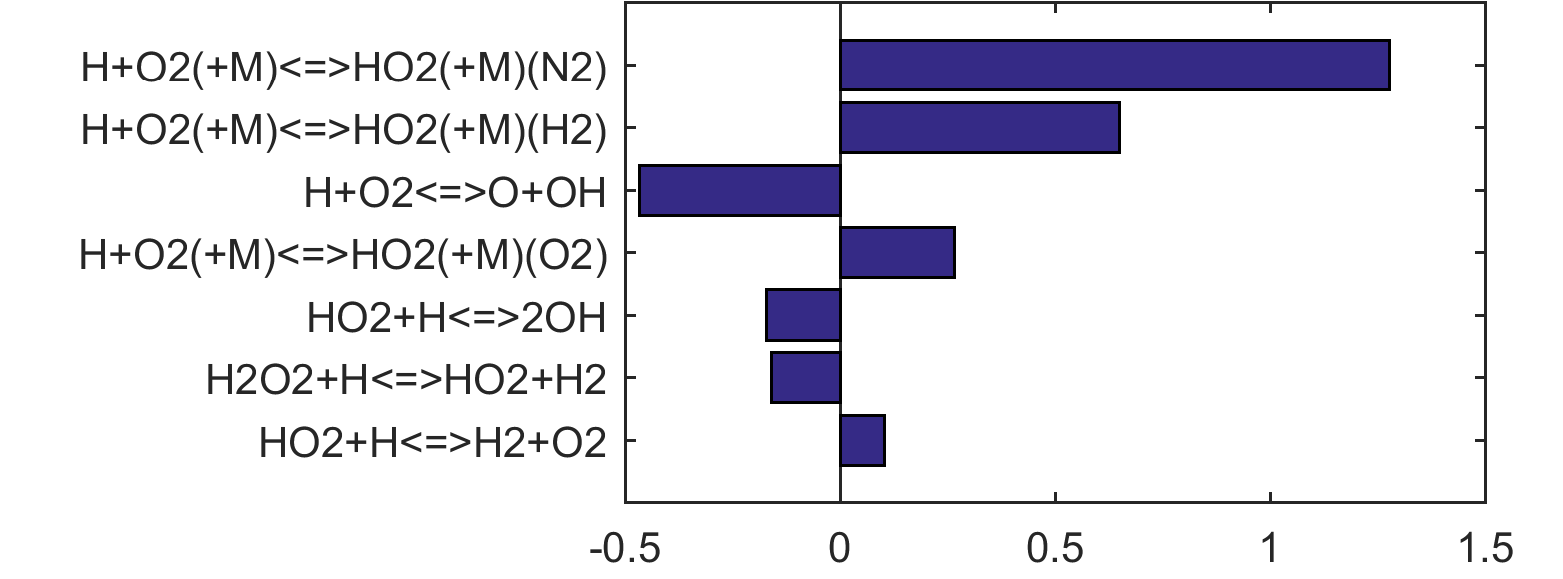

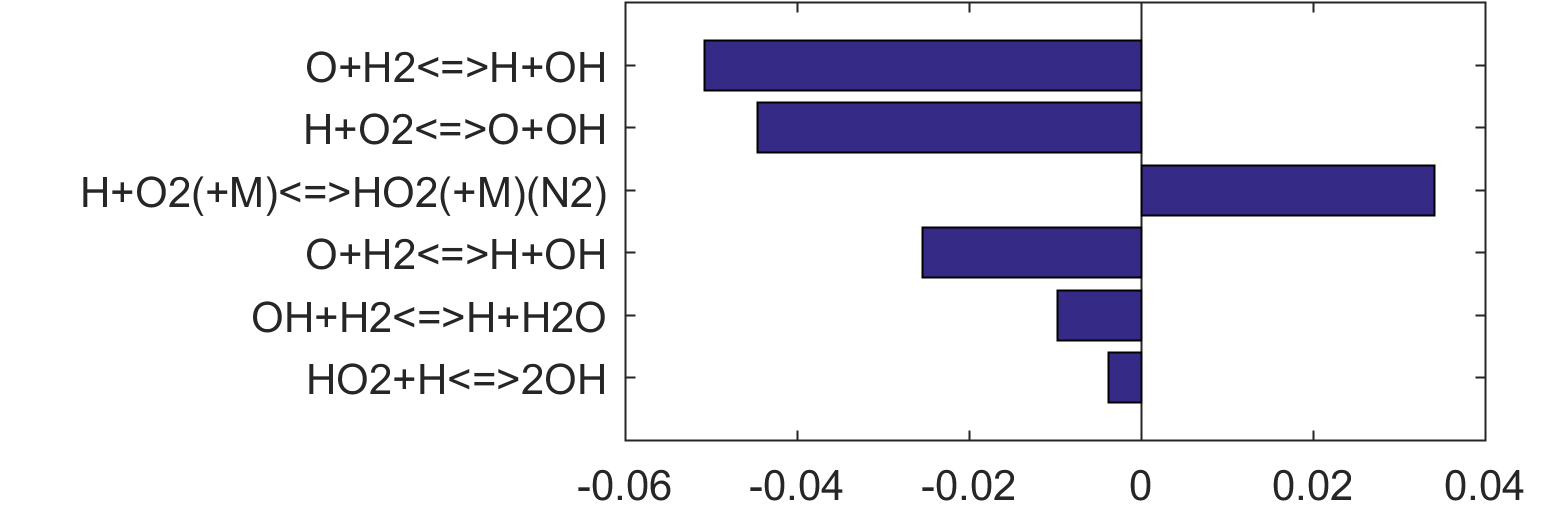

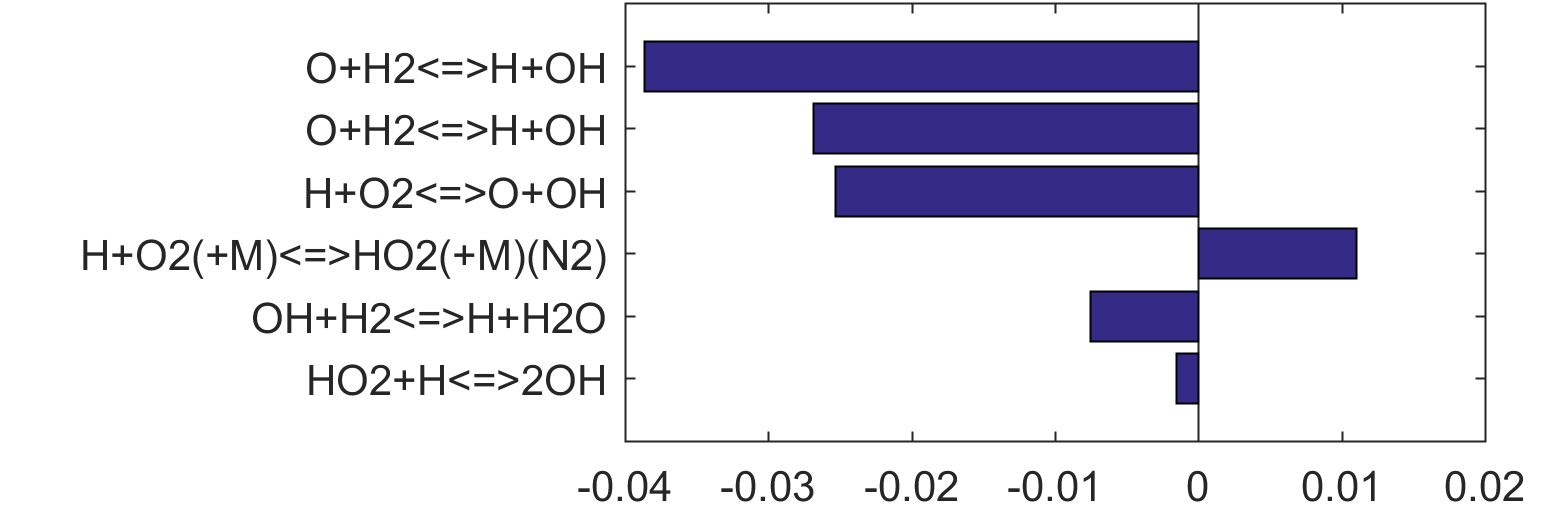

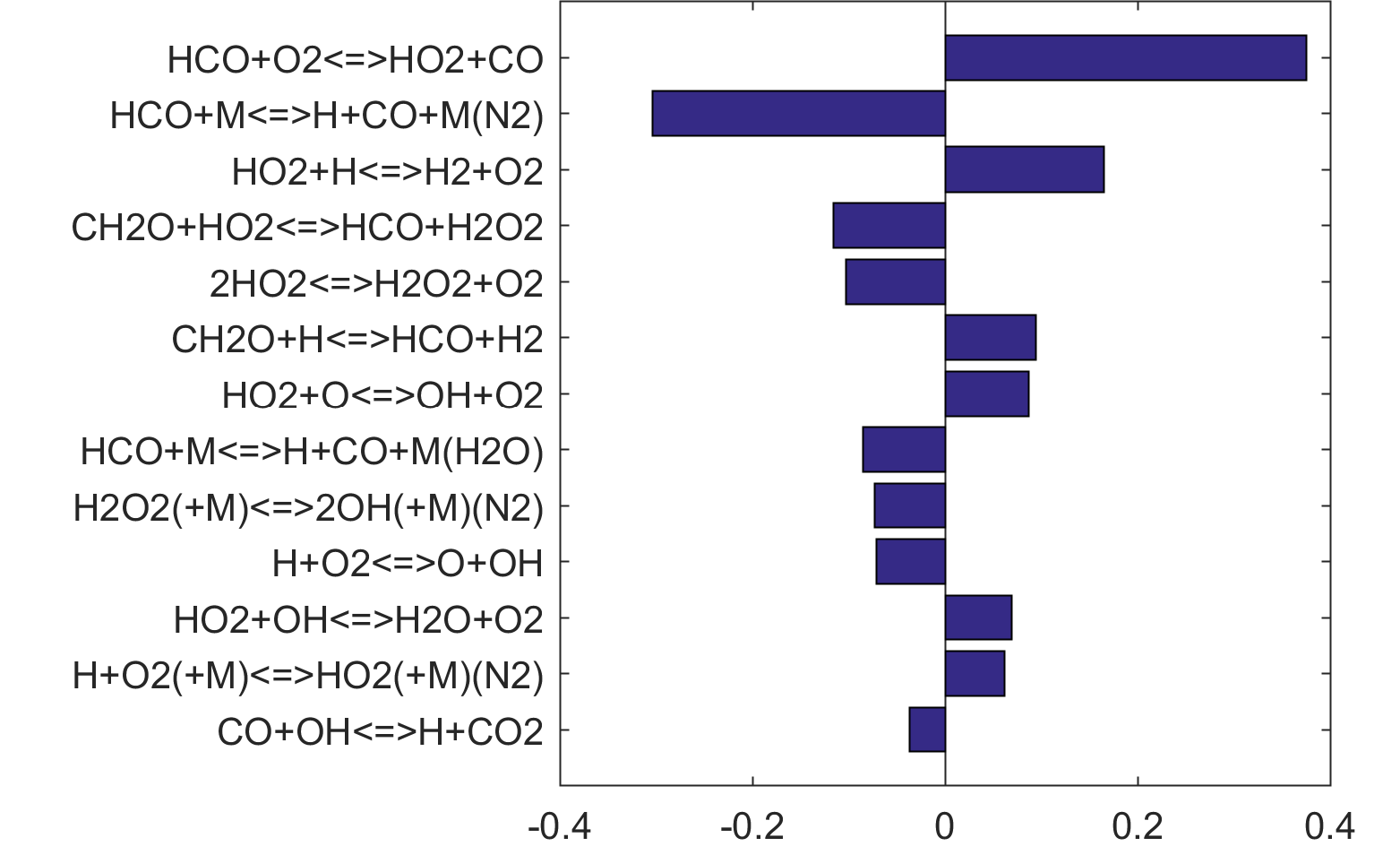

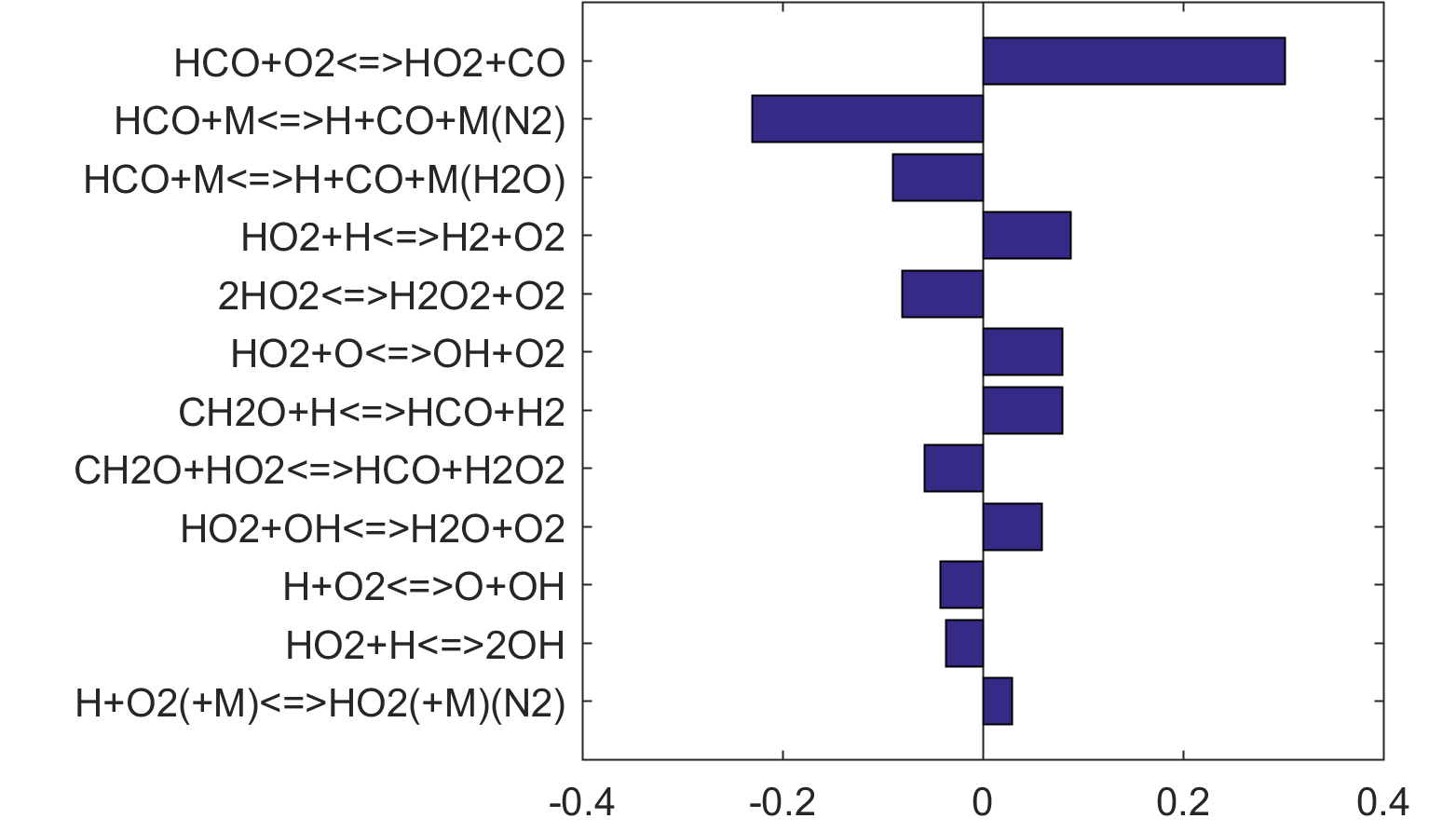

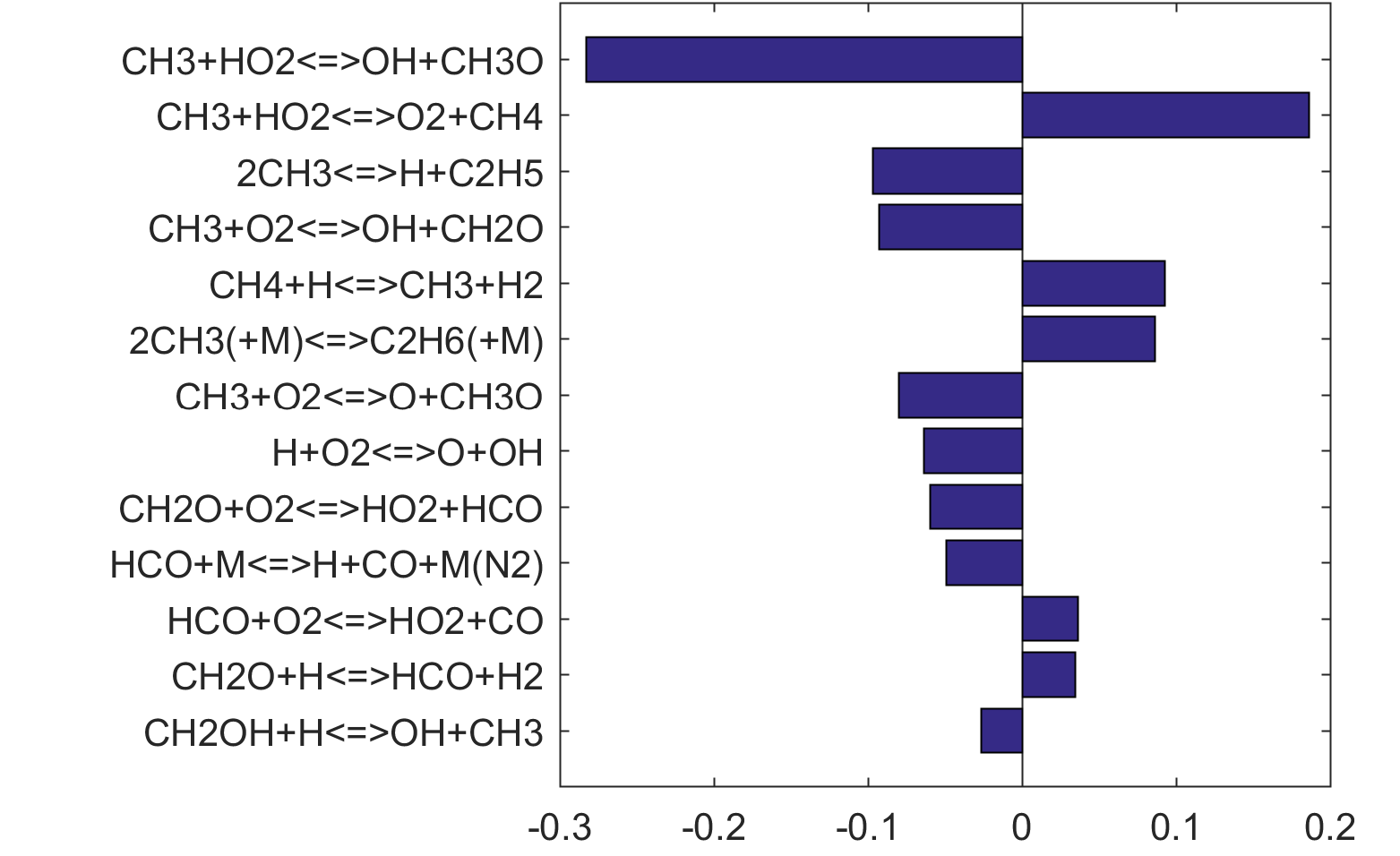

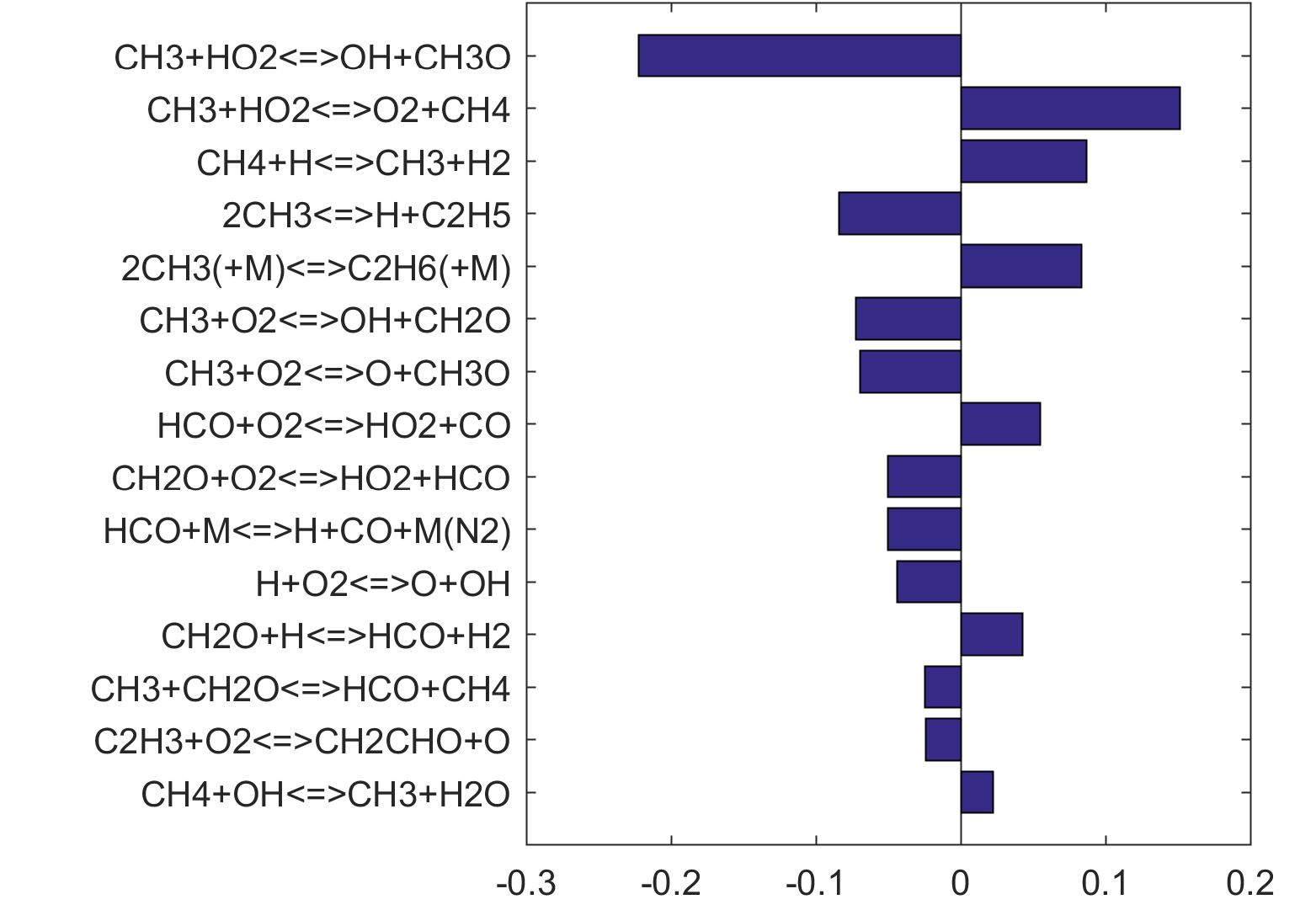

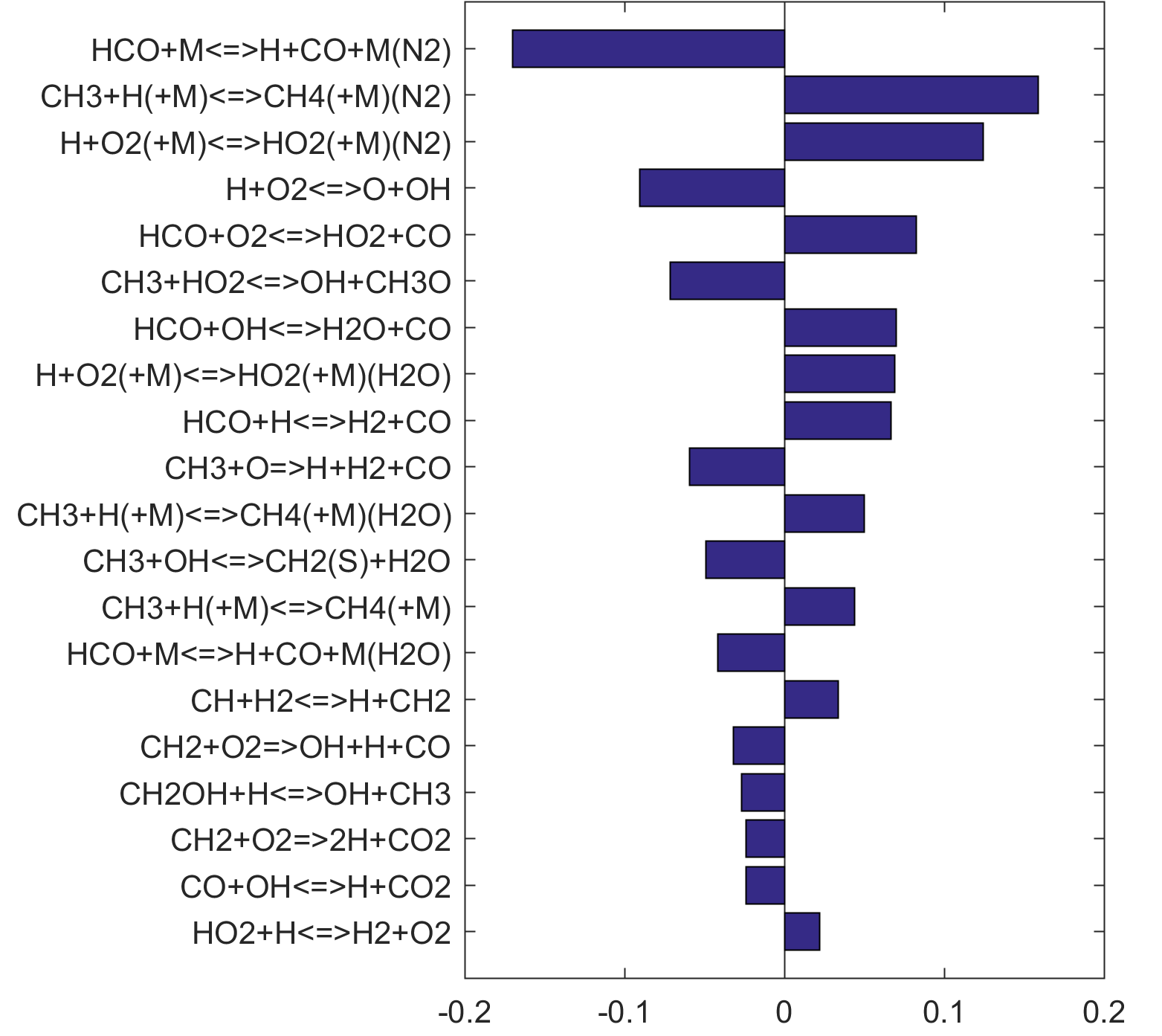

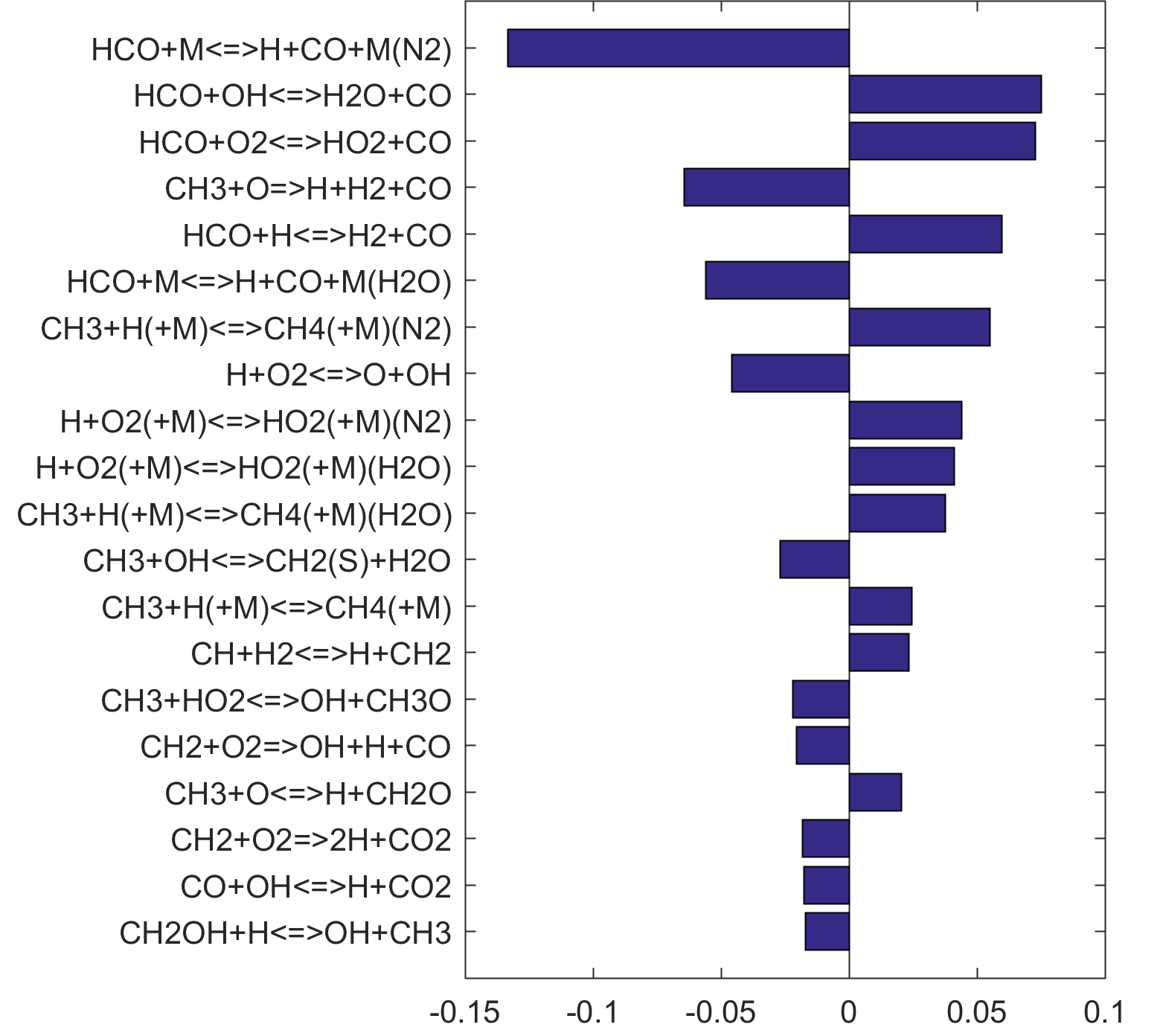

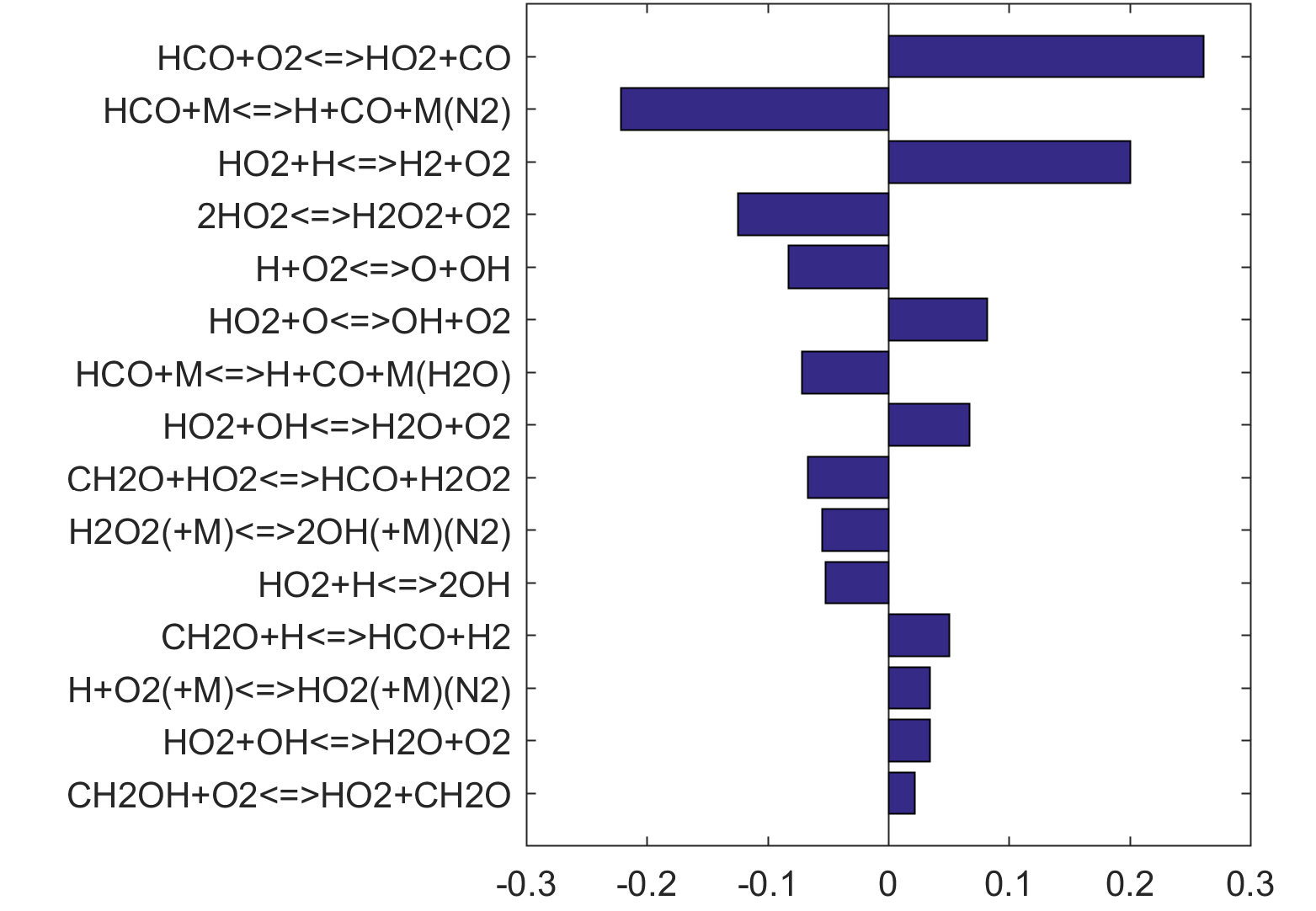

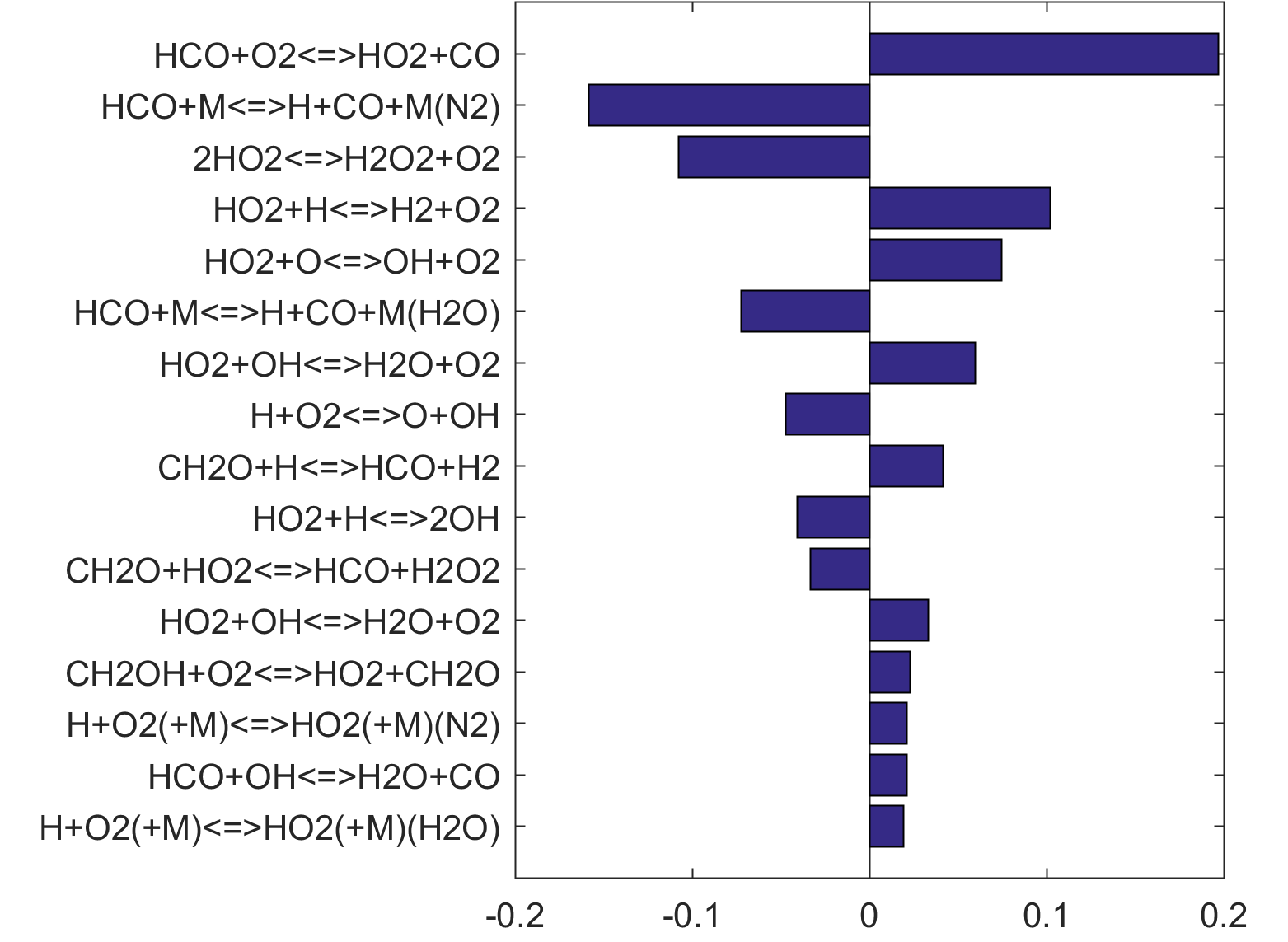

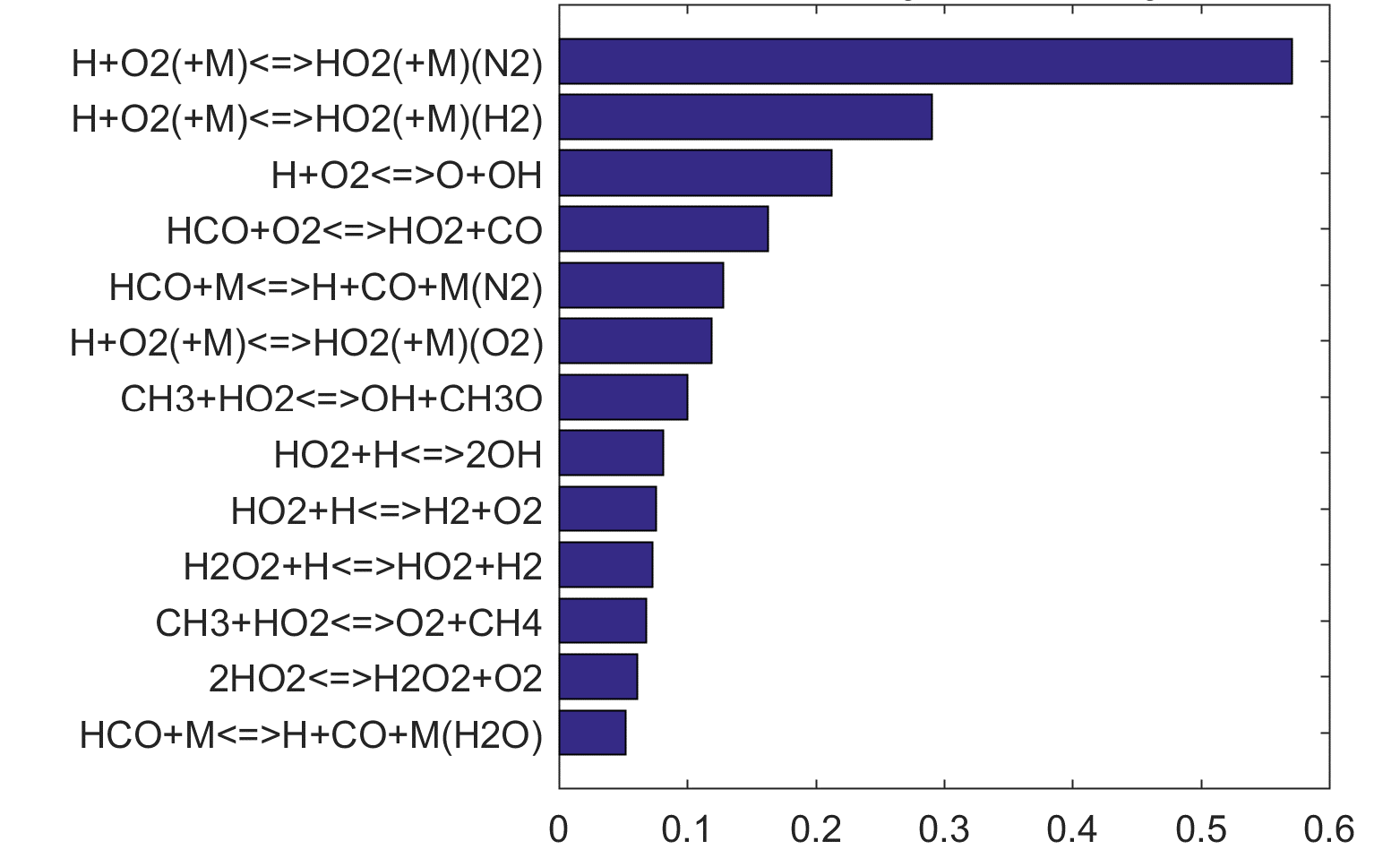

Within the combustion targets considered, key reactions may be identified on a target-by-target basis by examining the respective uncertainty × sensitivity graphs. We find it to be useful to examine the list of critical reactions in a composite fashion by rank orders over a wide range of targets. A reaction impact factor Ir may be defined for this purpose. Specifically, we have

$$I_r=\sqrt {\frac 1 {N_{fuel}}\sum_k \left[\frac 1 {n_{fuel_k}}\left(\frac 1 {\eta_k} \frac{\partial \eta_k^{\text {calc}}}{\partial x_r}\cdot\sigma_r\right)^2\right]}$$for flame speeds and

$$I_r=\sqrt {\frac 1 {N_{fuel}}\sum_k \left[\frac 1 {n_{fuel_k}}\left(\frac{\partial \eta_k^{\text {calc}}}{\partial x_r}\cdot\sigma_r\right)^2\right]}$$for shock-tube targets.

In the above equations, ηk is the kth target value (either a flame speed in cm/s or the natural log of ignition delay or a species concentration, xr is the normalized rate of reaction r, σr is the standard deviation of xr taken as ½ as xr is assumed to be normally distributed [15], nfuel,k is the number of targets of a specific fuel, and Nfuel is the total number of fuel systems considered in FFCM-1. They are H2, CO/H2, CH4, CH2O, and C2H6. The thus-defined impact factor of a reaction measures the influence of the uncertainty of its rate coefficient on a type of combustion target across the range of targets considered. The use of nfuel,k and Nfuel ensures that the factor is normalized with respect to the number of targets considered for a specific fuel system. In this way, Ir is general and unbiased towards a particular fuel.

Figures 2 and 3 show the composite ranking of Ir for flame speed and shock-tube targets, respectively. The plot in the left panel of each figure presents the result computed using the trial model, while the plot on the right shows results from the optimized model. Although the rank order is somewhat changed after optimization, key reactions stay the same. For flame speed, they include two of the three channels of H + HO2 reaction:

| HO2 + H = H2 + O2 | (R16) |

| HO2+ H = OH + OH | (R17) |

the H + O2 combination

| H + O2 (+M) = HO2 (+M) | (R15) |

especially for M= N2 and H2O, and several reactions involving the methyl radical:

| CH3 + HO2 = CH3O + OH | (R105) |

| CH3 + H (+M) = CH4 (+M) | (R97) |

For shock tube targets (Fig. 3), R15 remains the most critical. Other top-ranked reactions include CH2O reactions:

| CH2O + HO2 = HCO + H2O2 | (R91) |

| CH2O + O2 = HO2 + HCO | (R90) |

The above two reactions have large Ir values because they are critical to the CH2O targets considered, which were in fact designed to sensitize these reactions. If additional work on those reactions with Ir values ranked highly in Figs. 2 and 3 can narrow the rate uncertainty (or revise the values), the overall uncertainty space for the feasible kinetics models might be significantly reduced. This outcome would not apply to those reaction steps that have already been determined to high precision, for example, the reaction

| H2 + OH = H2O + H | (R4) |

for which tight uncertainty bounds have been given from a recent shock tube measurement [16].

|

|

Figure 2. Ranked reaction impact factor Ir of the trial and optimized models on all flame speed targets.

|

|

Figure 3. Ranked reaction impact factor Ir of the trial and optimized models on shock-tube targets.

2 Prediction Accuracy

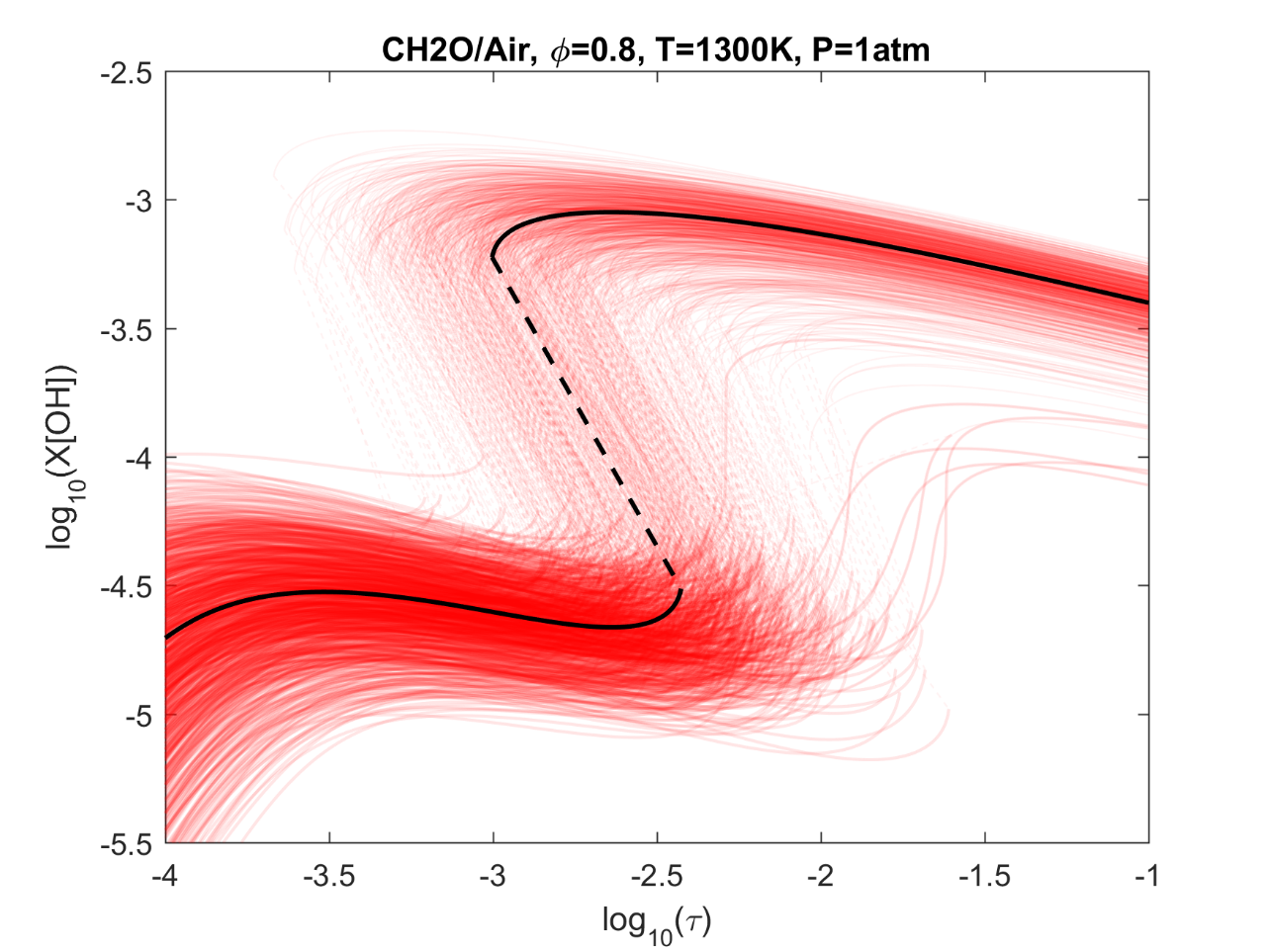

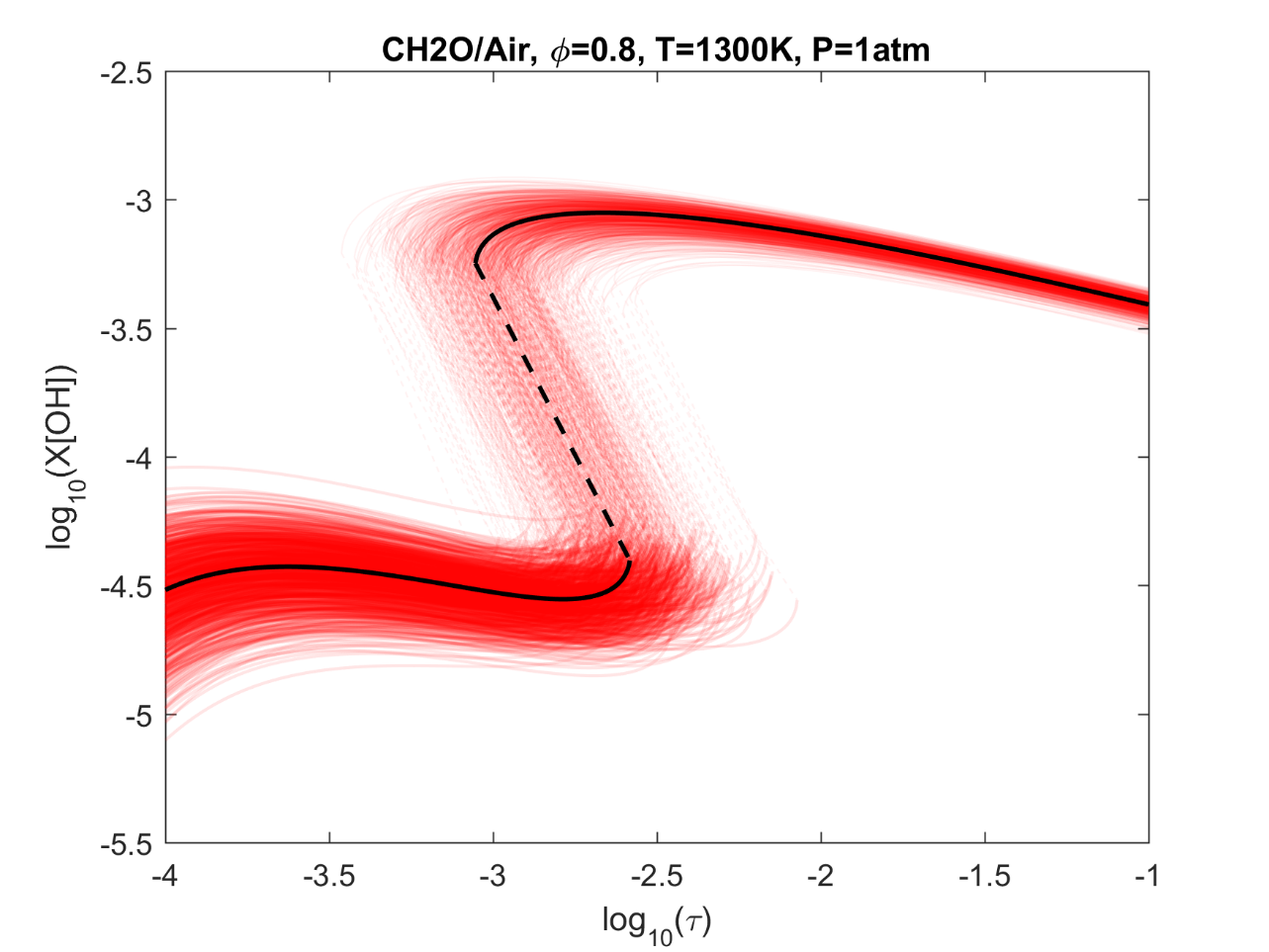

An equally interesting question is the accuracy of the optimized model for predictions of combustion response outside the type and the range of thermodynamic conditions for which the model is optimized. To address this question, we present numerical diagnostic results of the trial and optimized models using fuel oxidation in a perfectly stirred reactor (PSR) as an example. Conditions relevant to turbulent combustion, extinction for example, often occur at a time scale shorter than that can be measured reliably in well-stirred reactors. Achieving chemical accuracy is expected to be critical to turbulent flame simulation, yet the same condition and reaction regimes see an amplified impact from kinetic uncertainties in the ability of the reaction model to predict key reaction events accurately.

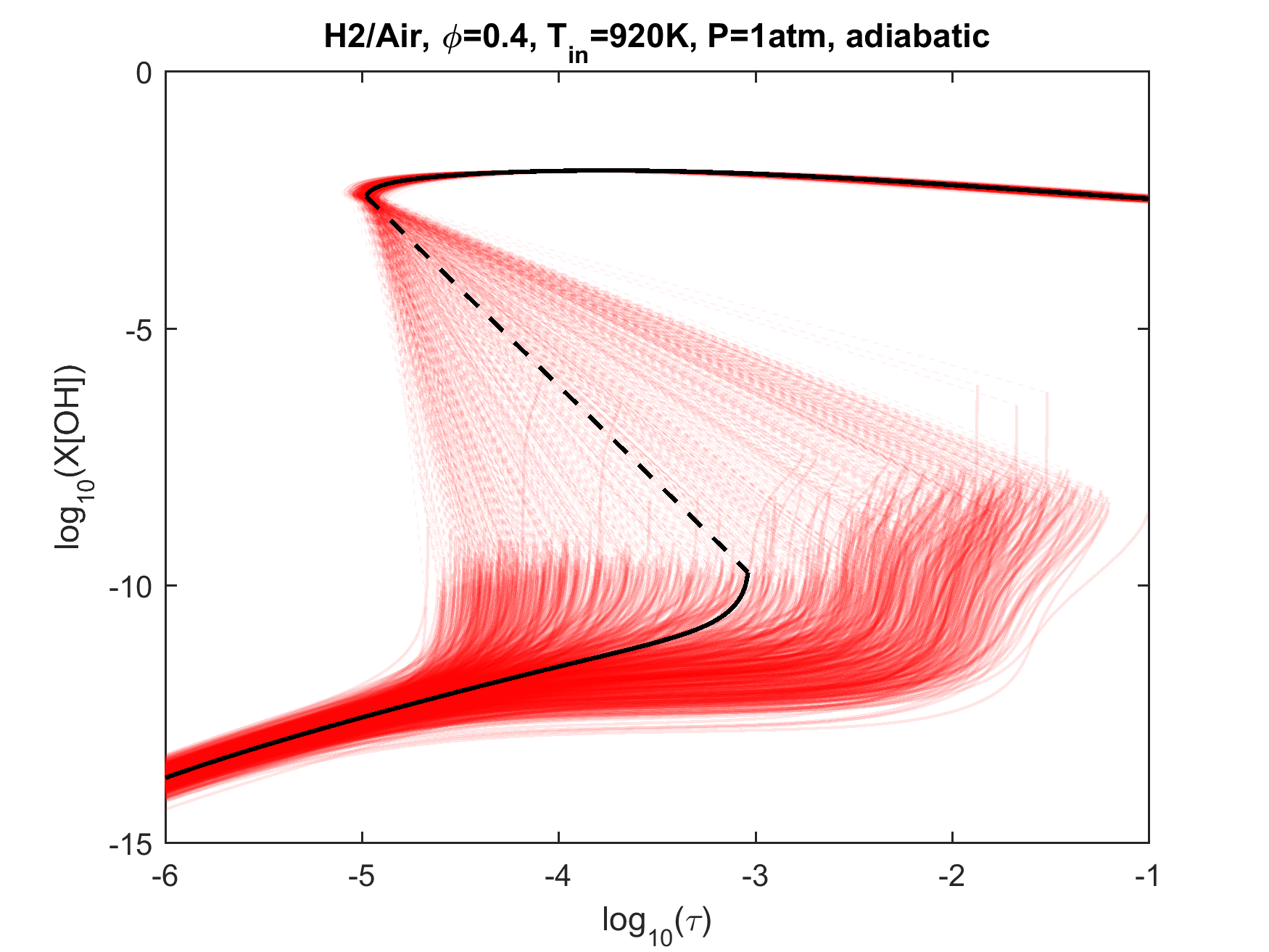

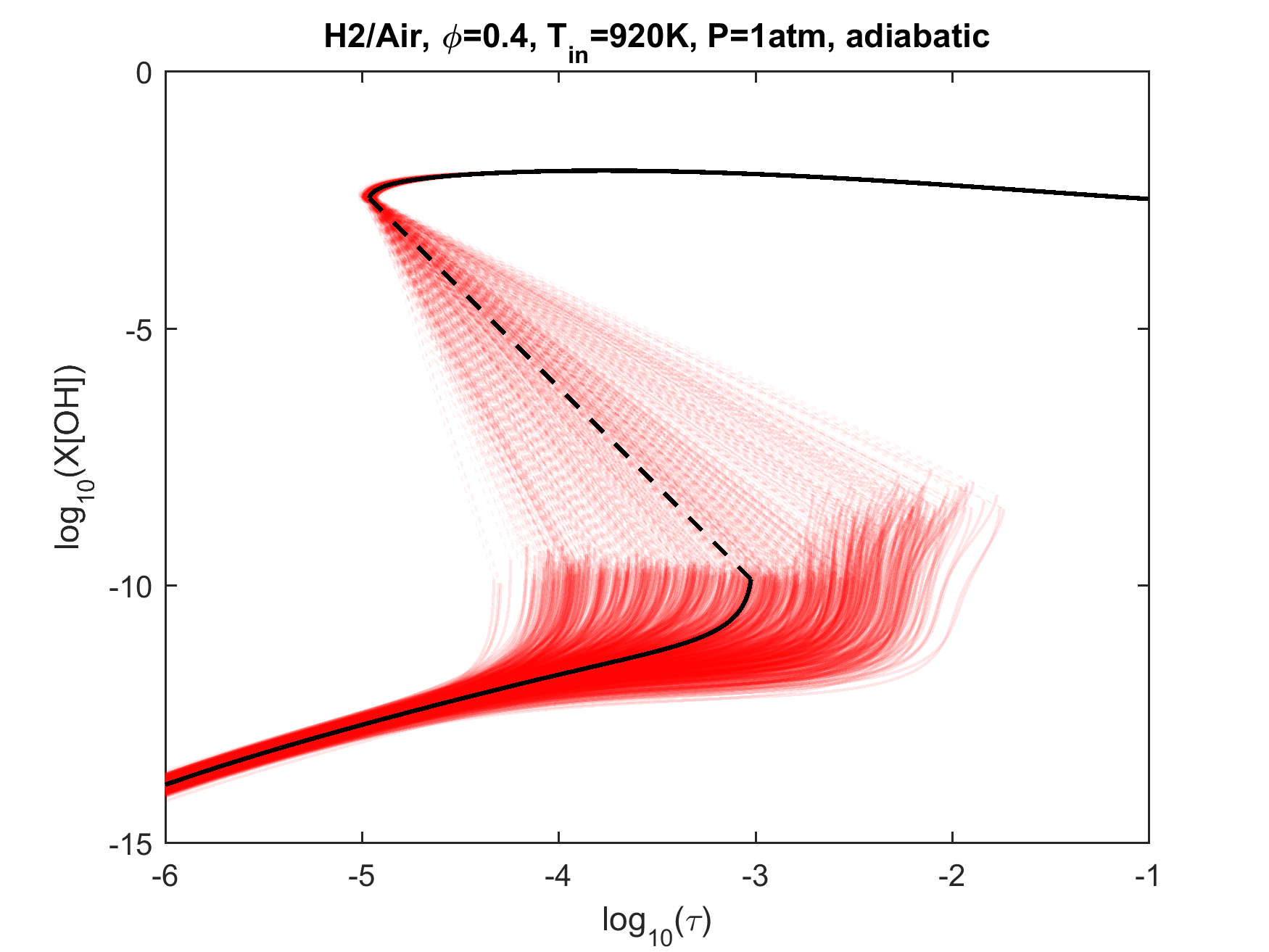

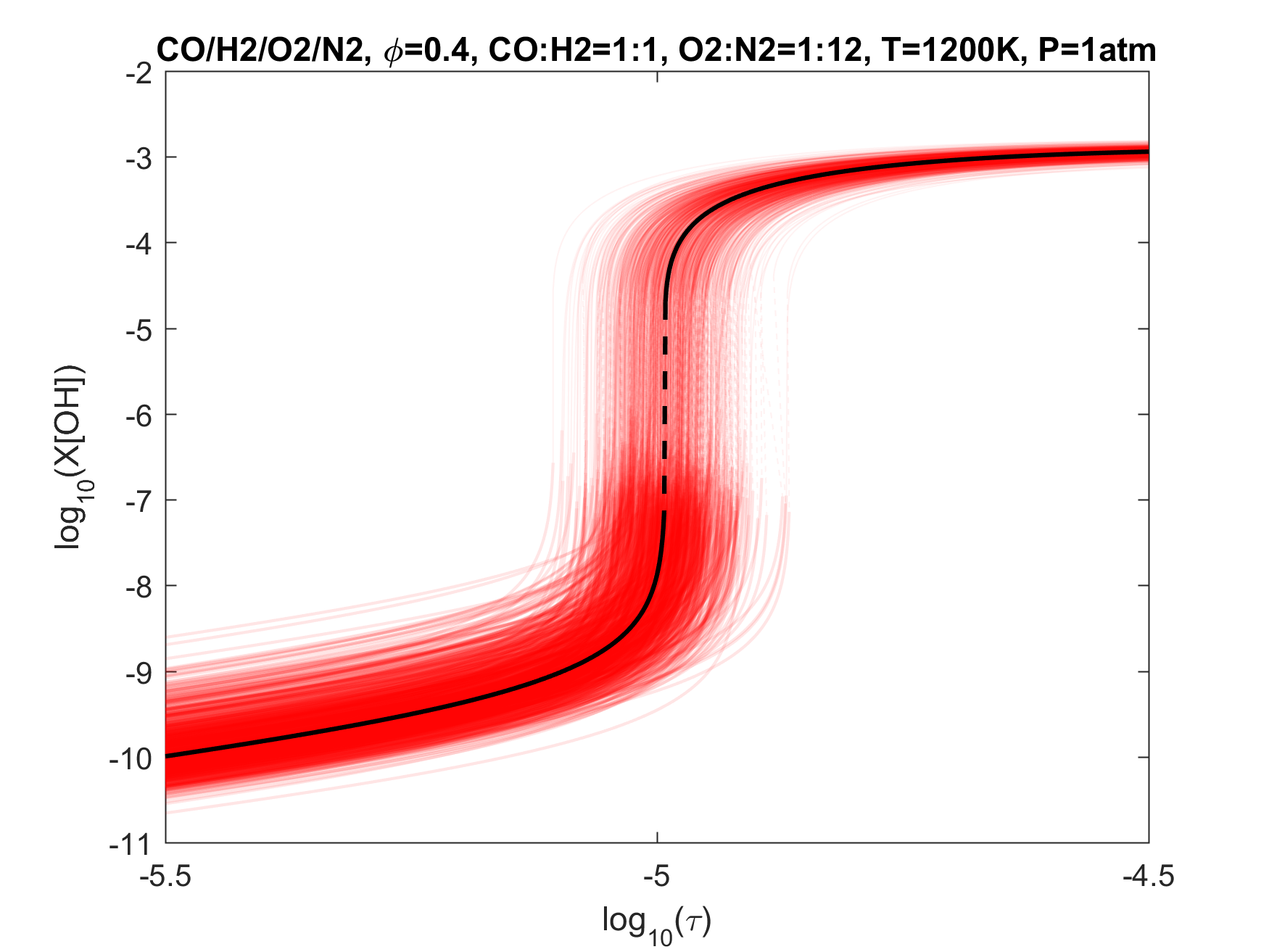

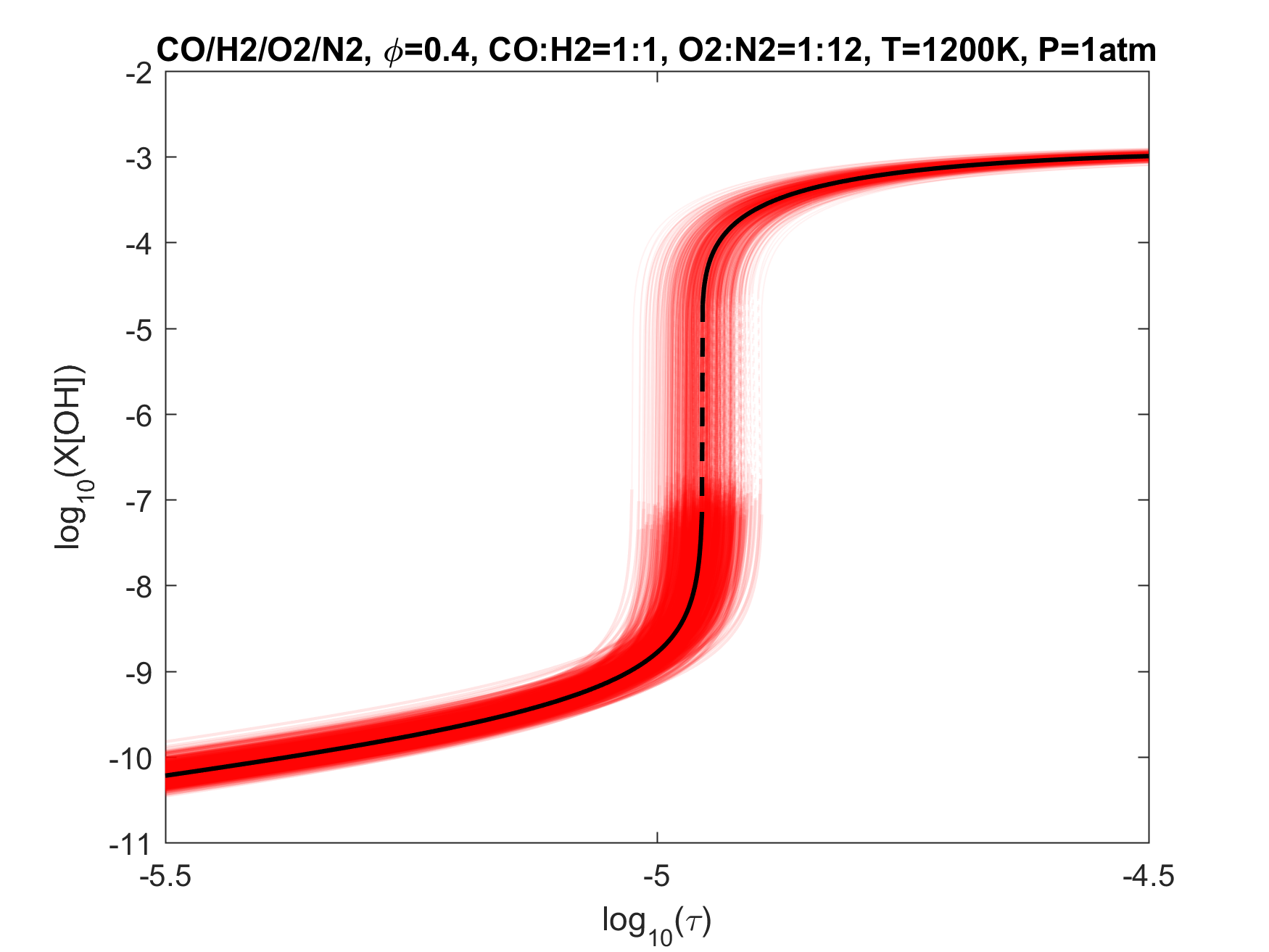

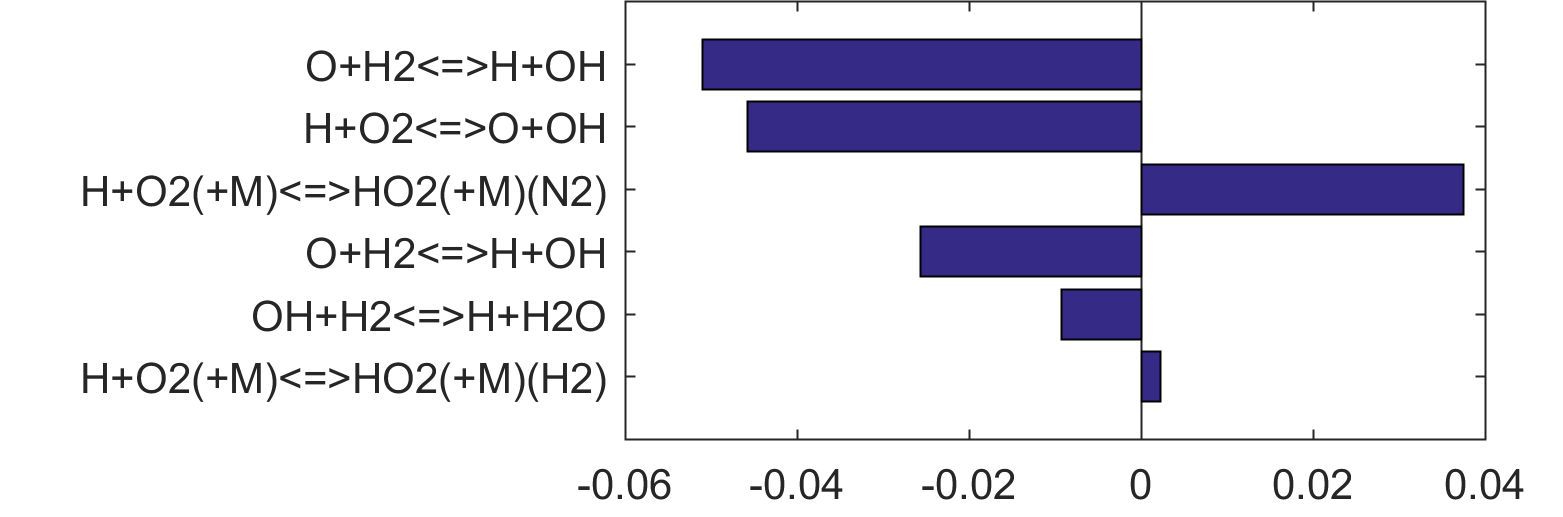

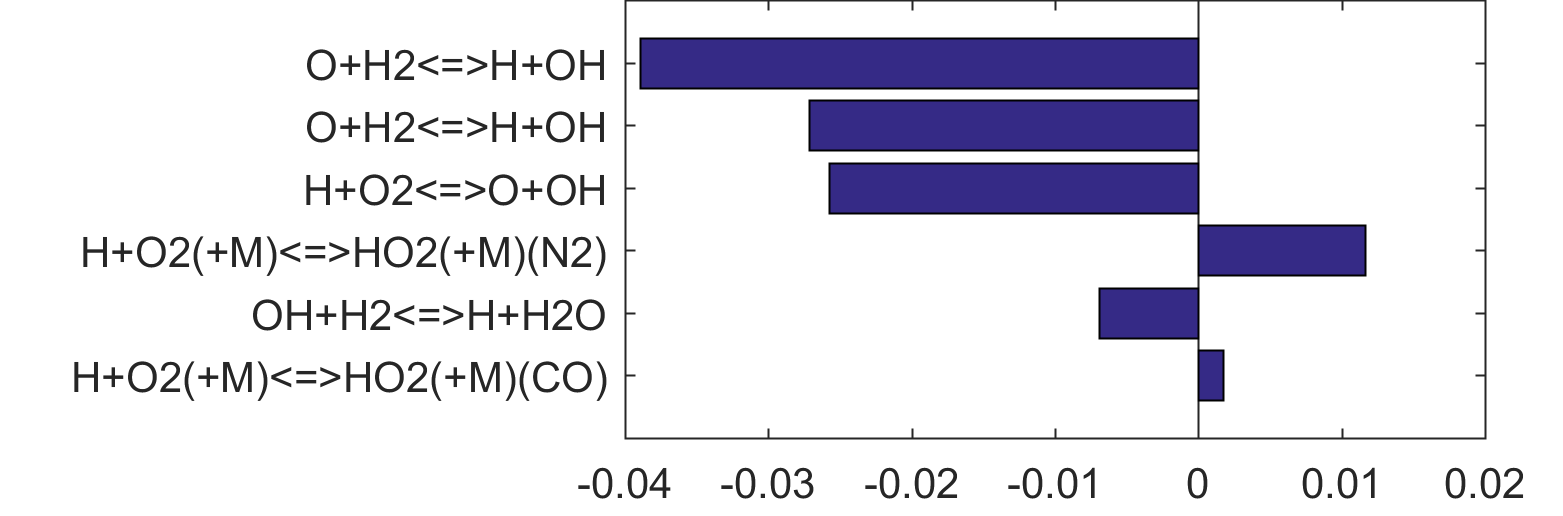

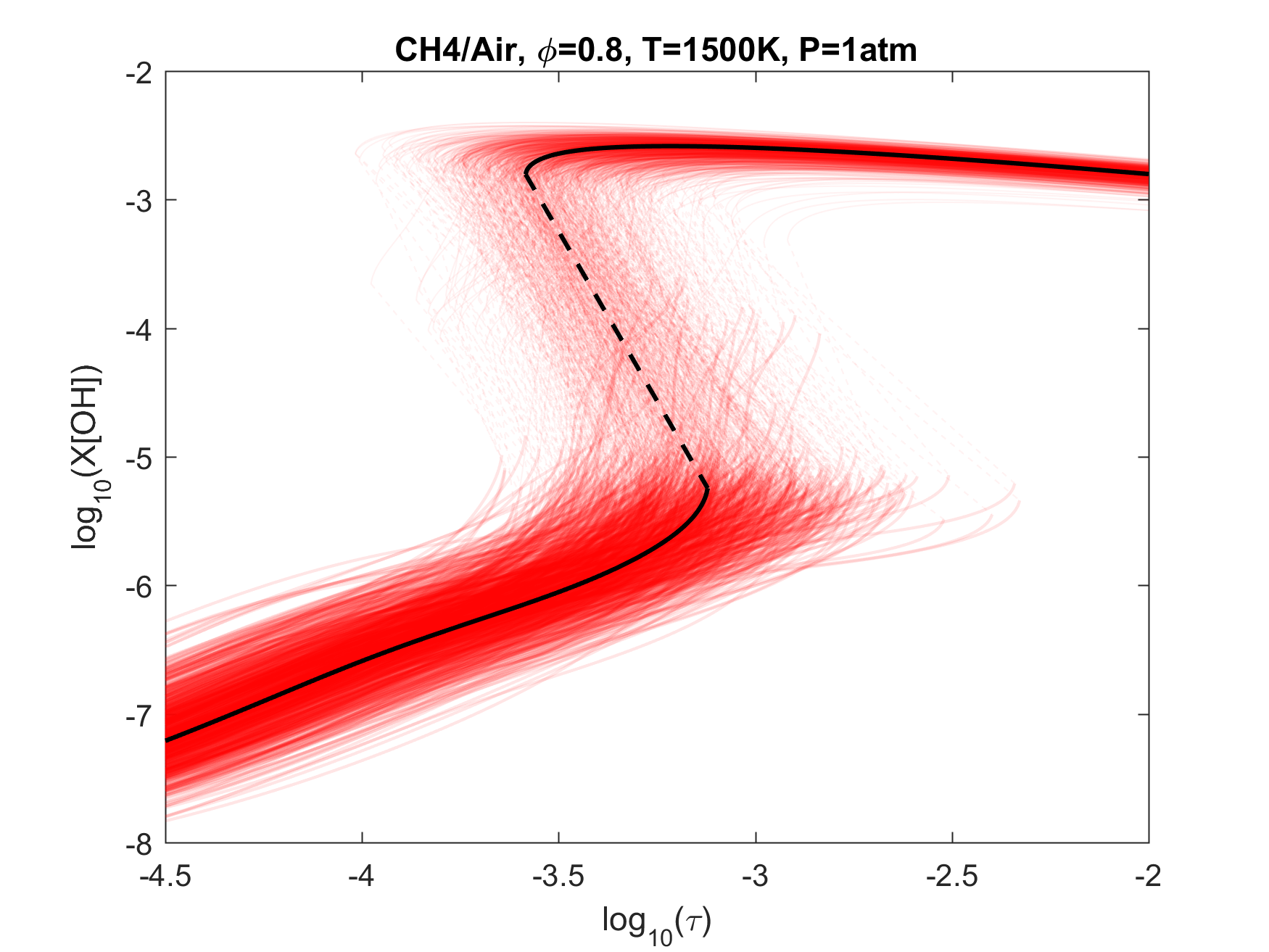

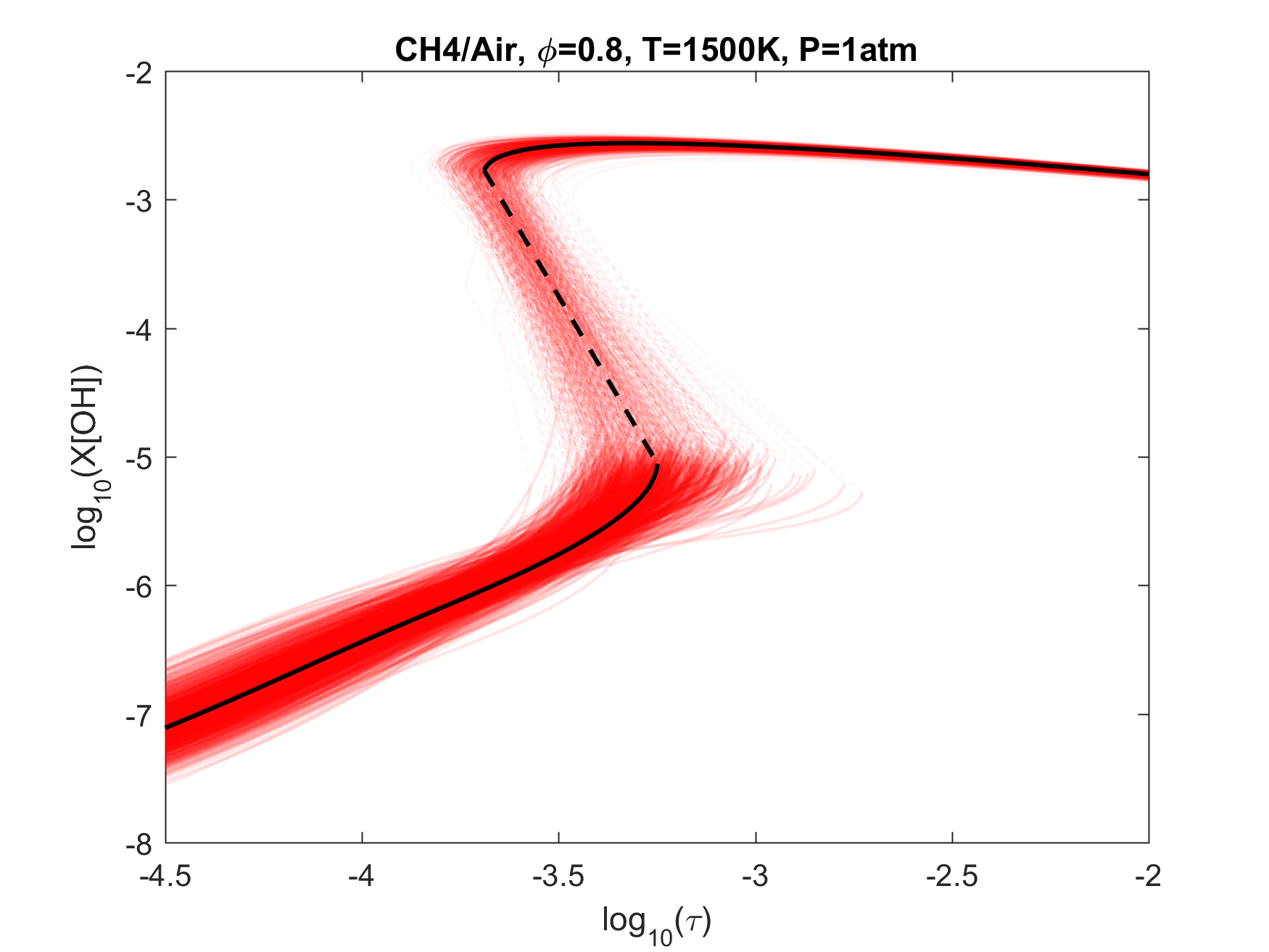

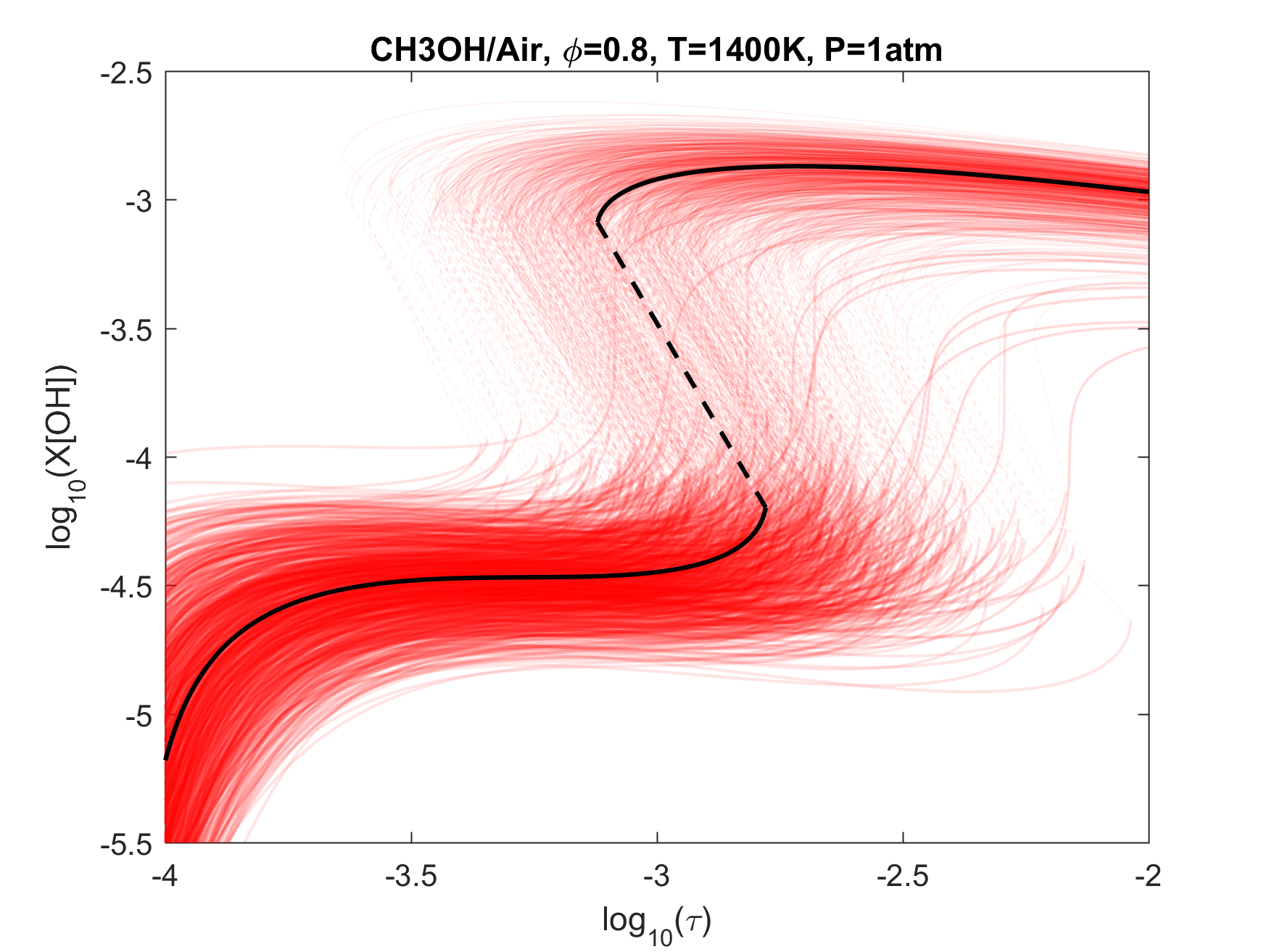

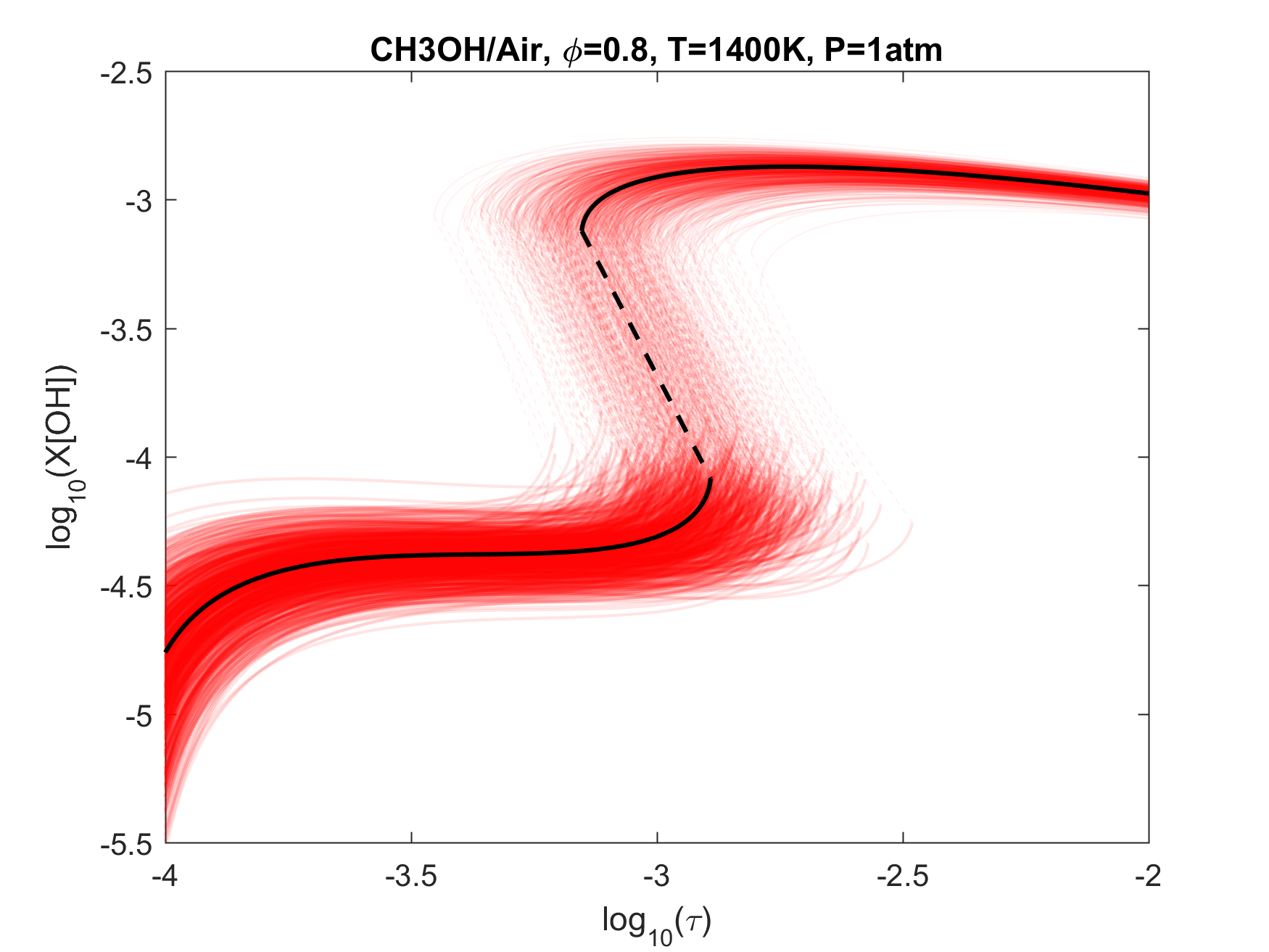

To illustrate the above point, we plot in Figs. 4-9 the results of Monte Carlo (MC) sampling of the parameter uncertainty spaces of the trial and optimized models, for OH concentration vs. residence time, for H2, CO/H2, CH2O, CH4 and C2H4 oxidation in air. With the exception of the 50%CO/50%H2 syngas mixture, all PSR conditions were chosen to give O(1 ms) of extinction and/or ignition residence times. A more rigorous and systematic analysis of the PSR system response to kinetic uncertainties is forthcoming. The current choices are somewhat random and limited. Nonetheless, several observations can be made from an inspection of these figures:

1. Optimization and uncertainty minimization led to a reduction in the prediction uncertainty of both extinction and ignition for all fuels tested;

2. With the exception of hydrogen, the model predictions remain unacceptably uncertain for both extinction and ignition, whether we use the trial or optimized model.

3. If local extinction and ignition events are critical to turbulent flame simulations, the accuracy of the chemical kinetic model needs to be improved drastically to obtain quantitative predictions for turbulent flames.

4. It would thus appear that the available precise target set is inadequate, and reliable lower temperature relevant targets need to be located or developed.

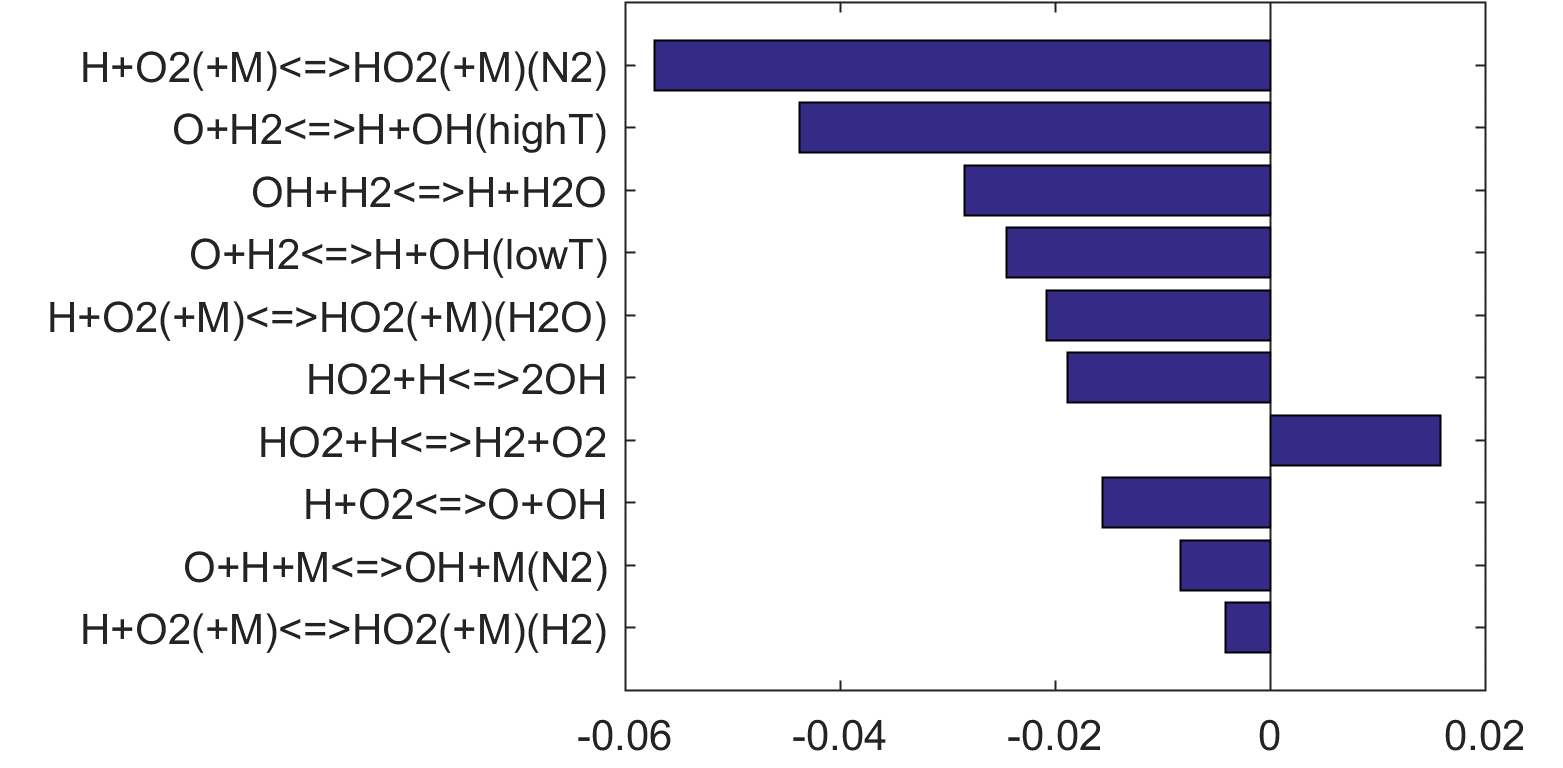

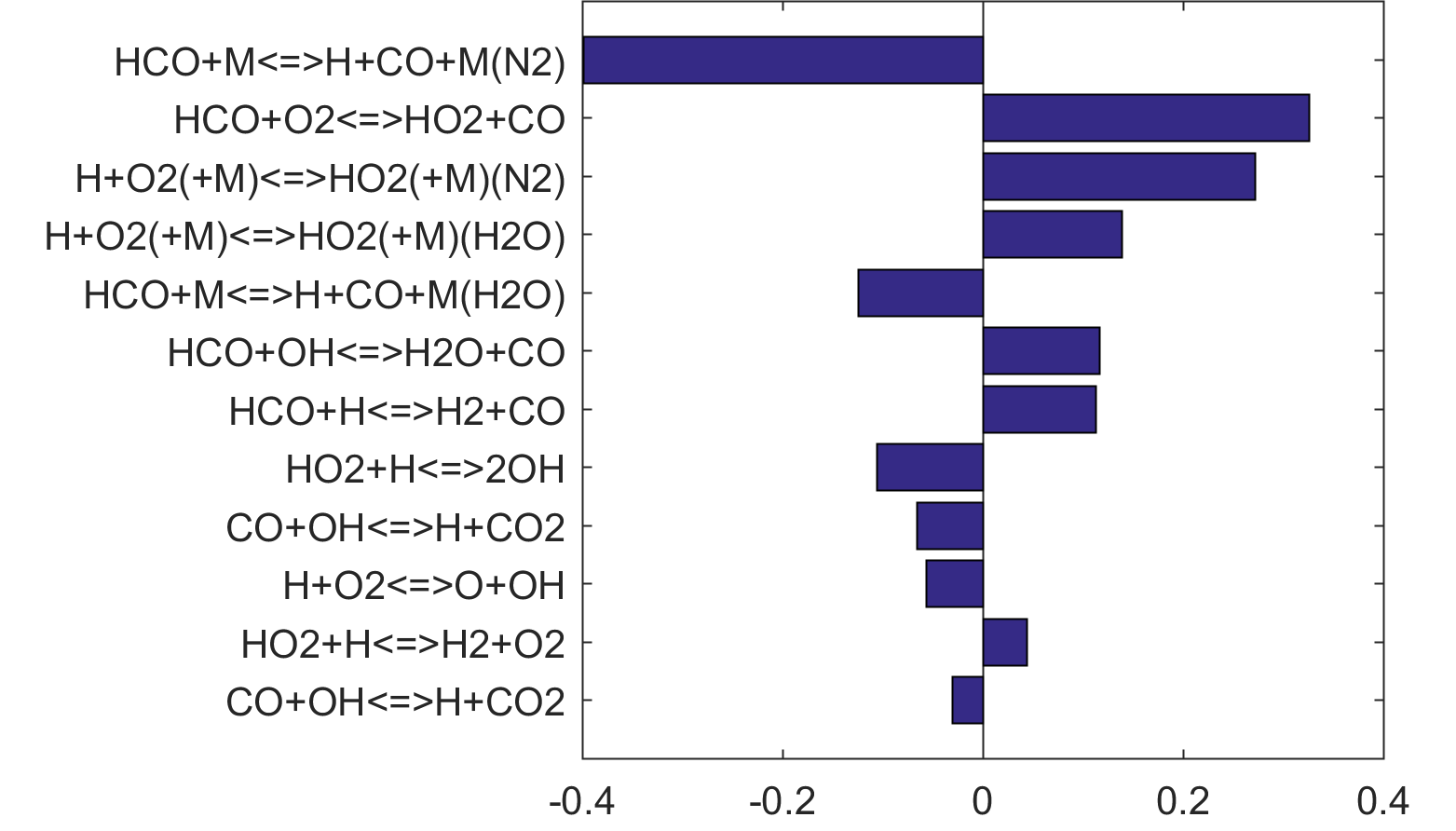

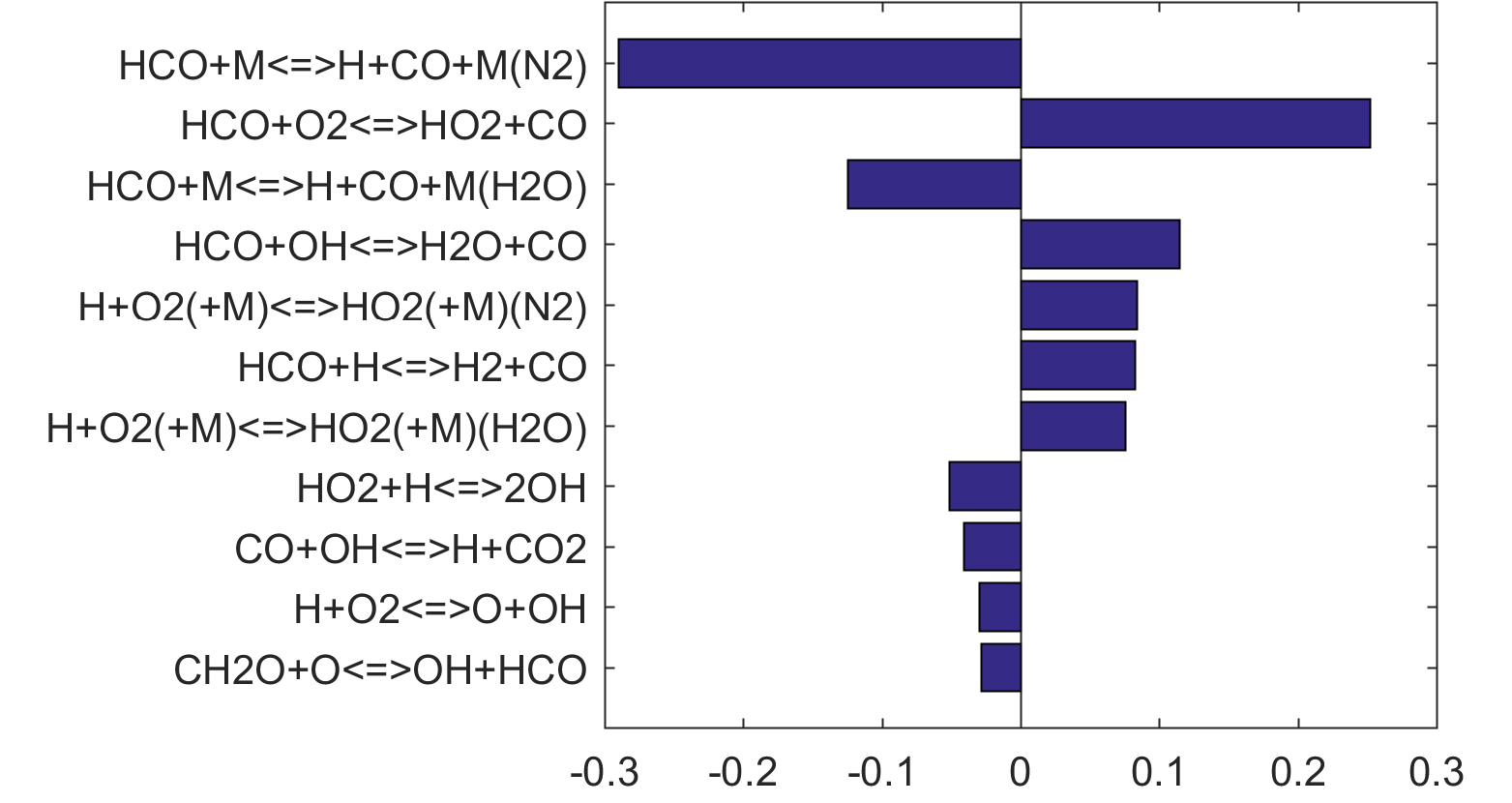

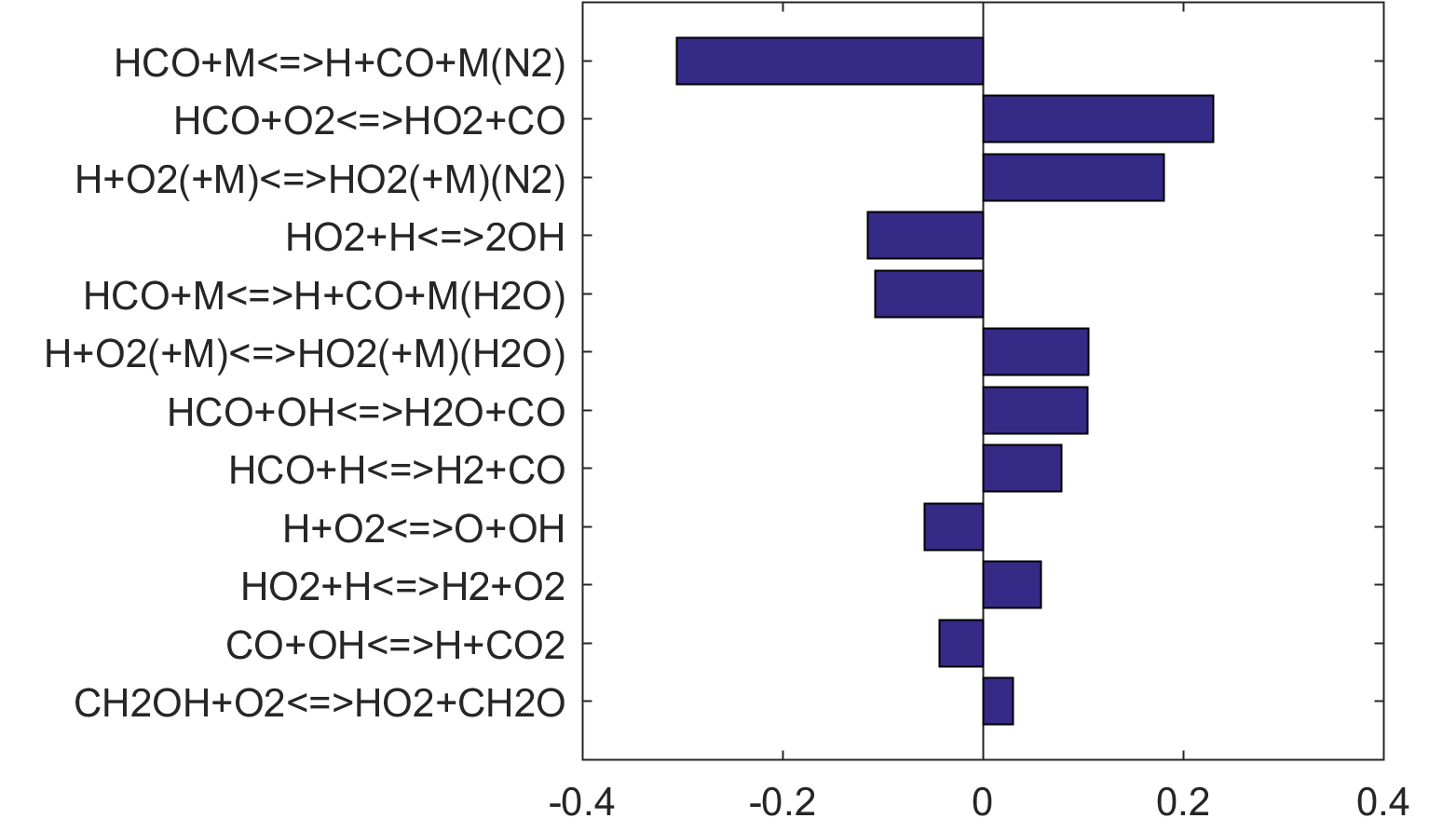

Reaction impact factor Ir can be obtained similarly using Eq. (2). Here, the gradient of the ln(τ) (either extinction or ignition) to reaction rates are estimated from a linear regression of the MC results. Ranked Ir charts are also shown in Figs 4 thru 8 for each fuel case, and in Figs. 9 and 10 when all cases are considered jointly. The ranking shown in Fig. 9 is highly skewed towards the ignition sensitivity of the H2 case (Fig. 4), it nonetheless highlights our critical needs: the model accuracy can be benefited in a significant way if the uncertainty factor of the rate coefficient of

| H + O2 (+M) = HO2 (+M) | (R15) |

can be reduced from the current level (a factor of 2) to about 20%, for M = O2 and H2, in addition to N2 and H2O already discussed before. The uncertainty of the rate coefficient of

| H + O2 = O + OH | (R1) |

is already at the 15% level [17] with little hope for improvement.

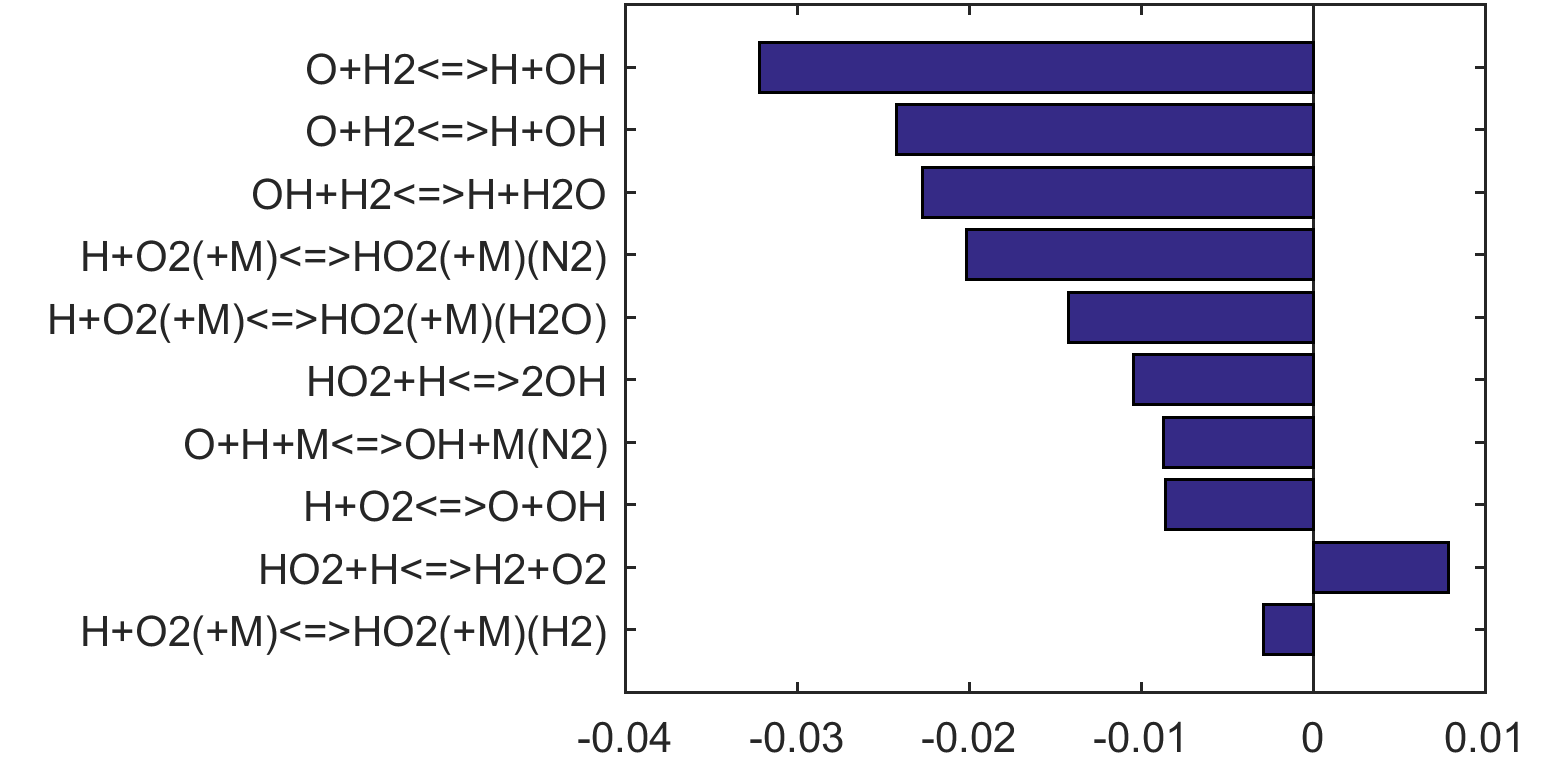

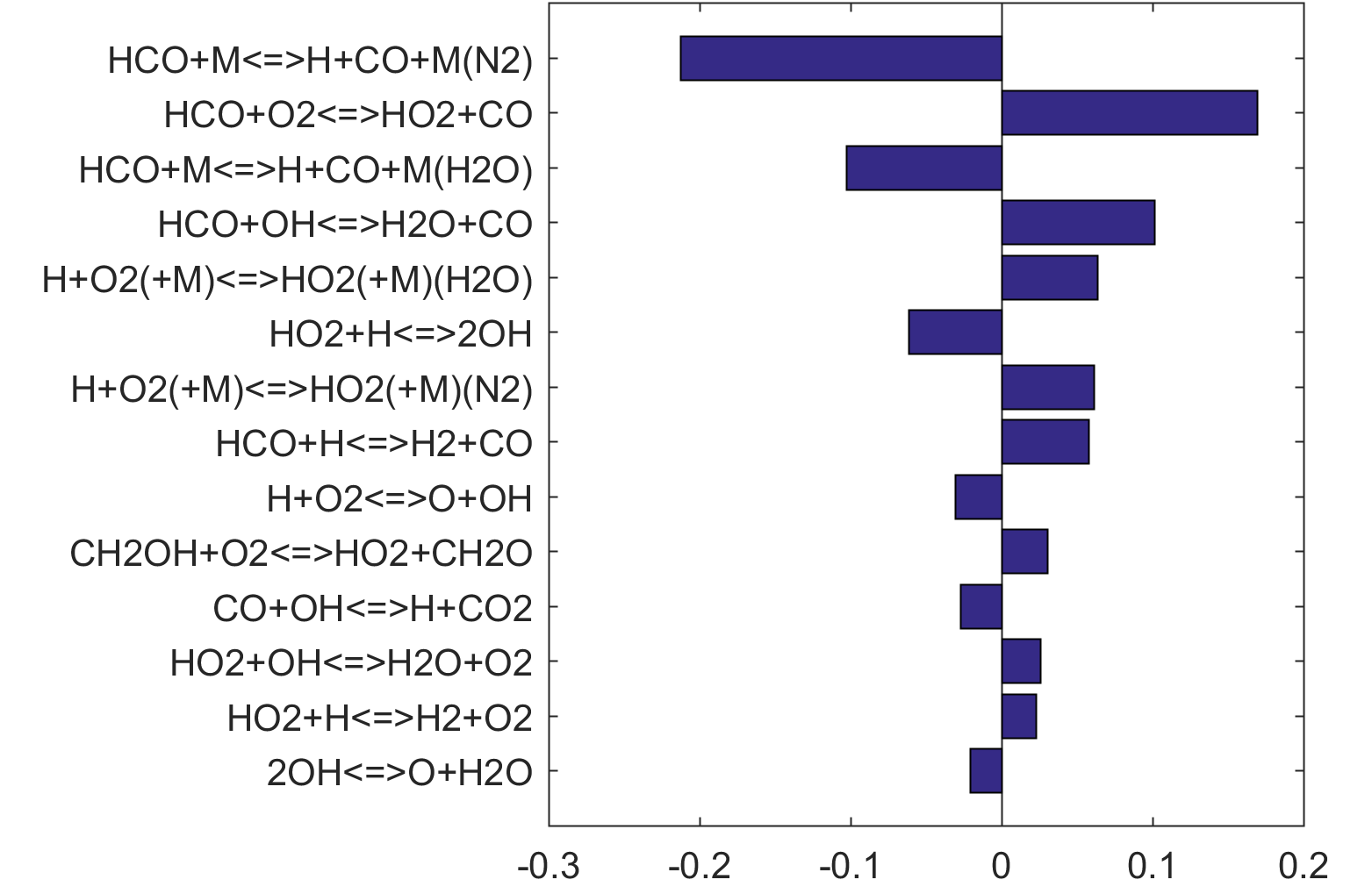

Figure 10 shows that key reactions that govern extinction of CH2O, CH3OH and CH4 oxidation are mostly the reactions of HCO. The destruction of HCO produces CO through several reactions, some of which have the effect of secondary chain branching (e.g., HCO + M = CO + H + M) while others are effectively chain terminating (e.g., HCO + H = CO + H2). All of the reactions are crucial to heat lease due to the subsequent reaction of CO + OH = CO2 + H. In general, the rate coefficients of the HCO reactions are accurate to within a factor of ~2. Clearly, the HCO reactions deserve prioritized studies. Improvements to these and other key reactions listed in Table 1 would significantly improve extinction predictability. We list a desired 20% uncertainty factor considering the best experimental and theoretical values that have been achieved thus far for a very small number of reactions. A 20% accuracy for each and every reaction of Table 1 would reduce the uncertainties in the extinction and ignition predictions by a factor of ~4 from those of the trial model, or to around the ±30% level in extinction and ignition residence time predictions for H2/CO, CH4, CH3OH and CH2O oxidation in a PSR. This may still be too large for reliable combustion simulations. Thus, further constraining of the mechanism by appropriate target experiments will also be required. It remains an open question what chemistry accuracy is required to achieve reliable simulation results under typical combustor conditions, which usually involve turbulent mixing. Regardless, the accurate prediction for hydrogen ignition may prove to be one of the most difficult tasks because of issues surrounding the ultra-sensitivity of combustion response to kinetics at or near the extended second explosion limit (see, section 2) and to impurities.

Table 1. Rate coefficients that require prioritized studies

|

No. |

Reaction |

Current uncertainty |

Desired uncertainty |

|

15 |

H + O2 ⇔ HO2 (k∞) |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

H + O2 +M ⇔ HO2 +M (M=N2) |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

H + O2 +M ⇔ HO2 +M (M=O2) |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

H + O2 +M ⇔ HO2 +M (M=H2O) |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

H + O2 +M ⇔ HO2 +M (M=CO2) |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

H + O2 +M ⇔ HO2 +M (M=H2) |

2 |

1.2 |

|

40 |

HCO + O2 ⇔ HO2 +CO |

2 |

1.2 |

|

35 |

HCO + M ⇔ H + CO + M (N2) |

1.7 |

1.2 |

|

|

HCO + M ⇔ H + CO + M (H2O) |

1.7 |

1.2 |

|

36 |

HCO + H ⇔ CO + H2 |

2.5 |

1.2 |

|

39 |

HCO + OH ⇔ CO + H2O |

2 |

1.2 |

|

16 |

HO2 + H ⇔ H2 + O2 |

2 |

1.2 |

|

17 |

HO2 + H ⇔ OH + OH |

2 |

1.2 |

|

2&3 |

O + H2 ⇔ H + OH |

1.6 |

1.2 |

|

105 |

CH3 + HO2 ⇔ CH3O + OH |

3 |

1.2 |

|

97 |

CH3 + H (+M) ⇔ CH4 (+M) (N2) |

3 |

1.2 |

|

|

CH3 + H (+M) ⇔ CH4 (+M) (H2O) |

3 |

1.2 |

|

|

Ir Ranking for Ignition |

|

|

|

Ir Ranking for Extinction |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Top panels: Monte Carlo sampling of the predicted mole fractions of OH as a function of residence time τ (sec) for H2 oxidation in air in an adiabatic PSR at 1 atm and with an inlet temperature of 920 K. The sample models are generated randomly over the rate coefficient uncertainties. Middle and bottom panels: ranked Ir values of ignition and extinction residence times calculated using Eq. (2). Left panel: trial model sampled over independent, lognormal distributions for individual rate parameters; right panel: optimized model sampled using the covariance matrix. Total sample size is 1000 each.

|

|

Ir Ranking for Ignition |

|

|

|

Ir Ranking for Extinction |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Monte Carlo sampling of the predicted mole fractions of OH as a function of residence time τ (sec) for an isothermal 50%CO/50%H2 syngas-like mixture oxidation in N2 diluted O2 in a PSR at 1 atm and 1200 K. The sample models are generated randomly over the rate coefficient uncertainties. Middle and bottom panels: ranked Ir values of ignition and extinction residence times calculated using Eq. (2). Left panel: trial model sampled over independent, lognormal distributions for individual rate parameters; right panel: optimized model sampled using the covariance matrix. Total sample size is 1000 each.

|

|

Ir Ranking for Ignition |

|

|

|

Ir Ranking for Extinction |

|

|

|

Figure 6. Monte Carlo sampling of the predicted mole fractions of OH as a function of residence time τ (sec) for isothermal CH2O oxidation in air in a PSR at 1 atm and 1300 K. The sample models are generated randomly over the rate coefficient uncertainties. Middle and bottom panels: ranked Ir values of ignition and extinction residence times calculated using Eq. (2). Left panel: trial model sampled over independent, lognormal distributions for individual rate parameters; right panel: optimized model sampled using the covariance matrix. Total sample size is 1000 each.

|

|

Ir Ranking for Ignition |

|

|

|

Ir Ranking for Extinction |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Monte Carlo sampling of the predicted mole fractions of OH as a function of residence time τ (sec) for isothermal CH4 oxidation in air in a PSR at 1 atm and 1500 K. The sample models are generated randomly over the rate coefficient uncertainties. Middle and bottom panels: ranked Ir values of ignition and extinction residence times calculated using Eq. (2). Left panel: trial model sampled over independent, lognormal distributions for individual rate parameters; right panel: optimized model sampled using the covariance matrix. Total sample size is 1000 each.

|

|

Ir Ranking for Ignition |

|

|

|

Ir Ranking for Extinction |

|

|

|

Figure 8. Monte Carlo sampling of the predicted mole fractions of OH as a function of residence time τ (sec) for isothermal CH3OH oxidation in air in a PSR at 1 atm and 1400 K. The sample models are generated randomly over the rate coefficient uncertainties. Middle and bottom panels: ranked Ir values of ignition and extinction residence times calculated using Eq. (2). Left panel: trial model sampled over independent, lognormal distributions for individual rate parameters; right panel: optimized model sampled using the covariance matrix. Total sample size is 1000 each.

Figure 9. Fuel-averaged reaction uncertainty impact factor Ir computed for the ignition of fuel oxidation in PSR (see, Figs. 4-8) using the optimized FFCM-1.

Figure 10. Fuel-averaged reaction uncertainty impact factor Ir computed for the extinction of fuel oxidation in PSR (see, Figs. 4-8) using the optimized FFCM-1.

3 Kinetics and experiments nearly the second explosion regime of hydrogen

As we discussed in the target data evaluation page, a significant number of literature ignition delay data can be impacted by trace impurities. Many of the Davis et al.'s [18] targets were removed from the current target set because of our computational evaluation of this effect. It is appropriate to comment on these removed targets. Figure 11 shows the (p5, T5) conditions of selected shock-tube hydrogen ignition delay measurements superimposed on the extended second explosion limit of hydrogen. Not surprisingly, those experiments with significant initial impurity effects tend to cluster around the second explosion limit. The exclusion of these targets leads to the problem that the reaction kinetics at or near the ever-important second explosion limit remain largely unconstrained by the remaining less-sensitive targets. This knowledge gap has thus led to the exceedingly large uncertainty in the ignition prediction of hydrogen oxidation in a PSR, as seen in Fig. 4. The pressure and temperature condition (1 atm and 920 K) of that PSR calculation also lies closely to the extended second explosion limit. Clearly, the underlying problem is, the more a kinetic experiment is sensitive to kinetics, the more unreliable that experiment can be or the less useful information it can provide. So the new targets needed to constrain the kinetics mentioned in the last section are difficult to investigate accurately. (It is also implied that one must also know trace concentrations for any model device simulations near the second limit.)

Clever shock-tube experiments that can circumvent the impurity effect is critically needed. We also strongly recommend that future shock tube experiments, whether they are species time history or ignition delay measurements, must consider and quantify the effect of initial impurity as well as the accuracy of the temperature behind reflected shock waves. Around 1000 K, the accuracy needed for the temperature is preferably ± 15 K or smaller.

Figure 11. Conditions of H2 ignition delay targets that are sensitive to initial impurities in comparison with the extended 2nd explosion limit of H2. Color scheme represents the logarithm of the ratio of 2k(H+O2=OH+O)/k(H+O2+Ar=HO2+Ar)]; symbols: target (p5, T5) conditions with the symbol size representing the sensitivity to initial impurity; solid line: 2k(H+O2=OH+O)/k(H+O2+M=HO2+M) = 1.

4 High-pressure syngas combustion

The accuracy of the FFCM-1 remains poor or uncertain for prediction of high-pressure syngas combustion. The consideration of a limited number of high-pressure syngas combustion targets led to the identification of two reactions that have been largely overlooked over the past several decades, as discussed before. They are

| CO + O (+M) = CO2 (+M) | (R30) |

| CO + O2 = CO2 + O | (R31) |

Currently, reliable experimental information on the rate parameters of these reactions is largely unavailable. For R30, direct measurements of high-pressure CO2 thermal decomposition would be useful. For R31, species time history measurements under conditions similar to ign_3a and ign_3b along with a substantially reduced uncertainty span in reaction

| O + H2 = H + OH | (R3) |

would allow substantially improved predictions for the flame speed and ignition delay of high-pressure syngas combustion.

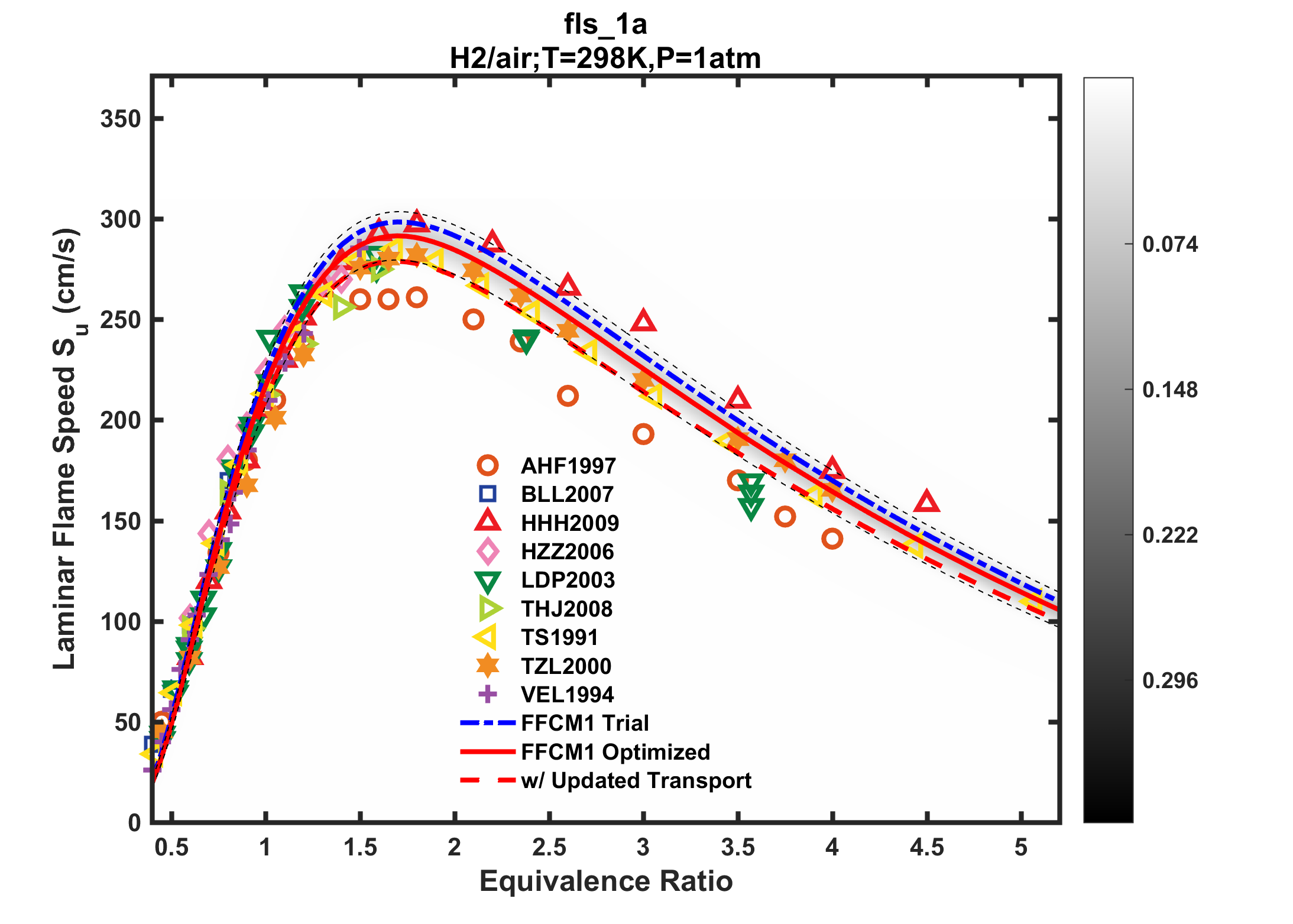

5 Transport parameters

Uncertainties in the transport parameters impact primarily the laminar flame speed of hydrogen through the molecular diffusivity of H and H2. In the current FFCM-1 release, we used the mutual diffusion coefficients of H atom in He, Ar, H2, O2, and N2 and of H2 in He, H2 and N2 from the quantum scattering calculations of Stallcop et al. [19-22] and Middha et al. [23,24] (see Transport Database description). The use of the earlier Sandia compilation produces a smaller diffusion coefficient for these light species because the Lennard-Jones inverse 12th power repulsive component is too stiff, and this gives smaller laminar flame speed values. The sensitivity coefficients of the flame speed with respect to the diffusion coefficient are generally positive [23,24]. Very recently, Dagdigian [25] proposed an even wider range of binary diffusion coefficients, including pairs that can have large effects on the molecular diffusivities of H and H2, including H-H2, H-O2, H-N2, H-H2O, H2-H2 and H2-N2, based on quantum scattering calculations [26-28]. An assessment of the impact of Dagdigian's revision shows lowered H2-air flame speed values, as shown in Fig. 12. Future FFCM efforts will be directed at incorporating these updates, and perhaps also consider transport parameter uncertainty in model optimization and uncertainty minimization.

Figure 12. Impact of updated transport coefficients based on Dagdigian's revised diffusion coefficients on the calculated laminar flame speed of hydrogen-air mixtures at 298 K and 1 atm.

6 Combustion targets

FFCM-1 used 146 fundamental combustion target data points. The constraints offered by the targets provide us with joint-probability information for the rate parameters that reduce the model prediction uncertainties. Yet each type of experimental target has its limitations or problems. Though they are carefully selected and evaluated, and appear to be self-consistent within the framework of the reaction model, data accuracy remains a key challenge to achieving predictive model accuracy.

In general, all individual laminar flame speeds measurements appear to have underestimated uncertainties; this is clear when we compare measurements and stated error bars from different facilities (see the data evaluation page). Many of the flame speed data rely on theory-based extrapolations to remove the flame stretch effect. In some cases, experimental data cannot be reconciled with the model within its uncertainty. It remains an open question how much useful guidance laminar flame speed measurements can provide to reaction model development, beyond proving that the model is not wrong. The recent advances of high-pressure flame speed measurement technique may prove to be critical to future development, as such experiments amplify kinetic sensitivity.

There are also uncertainties inherent in the model-based properties themselves that can have large effects on potential target values. Unavoidable, undeterminable impurity levels, and temperature or uniformity uncertainties are prime examples. Of course, as we have seen, conditions sensitive for ignition and extinction will likely also be sensitive to such factors. Developing targets sensitive mostly to the kinetics is a clear experimental design issue. Other more novel conditions could also lead to additional constraints on the combustion kinetics.

7 References

| [1] | Goldsmith CF, Harding LB, Georgievskii Y, Miller JA, Klippenstein SJ. Temperature and pressure-dependent rate coefficients for the reaction of vinyl radical with molecular oxygen. J Phys Chem A. 2015;119:7766-79. |

| [2] | Labbe, NJ, Sivaramakrishnan, R, Goldsmith, CF, Georgievskii, Y, Miller, JA, Klippenstein, SJ. Weakly bound free radicals in combustion: 'Prompt' dissociation of formyl radicals and its effect on laminar flame speeds. J Phys Chem Lett 2016;7:85-9. |

| [3] | Labbe, NJ, Sivaramakrishnan, R, Goldsmith, CF, Georgievskii, Y, Miller, JA, Klippenstein, SJ. Ramifications of including non-equilibrium effects for HCO in flame chemistry. Proc Combust Inst (2016) 36. in press (DOI: 10.1016/j.proci.2016.06.038). |

| [4] | Troe J. Thermal dissociation and recombination of polyatomic molecules. Symp (Int) Combust. 1975;15:667-80. |

| [5] | Jasper AW, Dawes R. Non-Born–Oppenheimer molecular dynamics of the spin-forbidden reaction O(3P) + CO(X 1Σ+)→ CO2(X̃1Σg+). J Chem Phys. 2013;139:154313. |

| [6] | Sun H, Yang SI, Jomaas G, Law CK. High–pressure laminar flame speeds and kinetic modeling of carbon monoxide/hydrogen combustion. Proc Combust Inst. 2007;31:439–46. |

| [7] | Burke MP, Chaos M, Ju Y, Dryer FL, Klippenstein SJ. Comprehensive H2/O2 kinetic model for high-pressure combustion. Int J Chem Kinet. 2012;44:444-74. |

| [8] | Verdicchio M, Jasper AW, Pelzer KM, Georgievskii Y, Klippenstein SJ High-level pressure-dependent kinetics for the H + O2 (+M) → HO2 (+M) reaction. A priori solution of the two-dimensional master equation. 9th U. S. National Combustion Meeting, the Combustion Institute, May 17-20, 2015, Cincinnati, Ohio. |

| [9] | Petersen EL, Davidson DF, Röhrig M, Hanson R. High-pressure shock-tube measurements of ignition times in stoichiometric H2/O2/AR mixtures. In: Sturtevant B, Shepherd JE, Hornung HG, editors. Proceedings of the 20th international symposium on shock waves; 1996; Pasadena, California. p. 941-6. |

| [10] | Urzay J, Kseib N, Davidson DF, Iaccarino G, Hanson RK. Uncertainty-quantification analysis of the effects of residual impurities on hydrogen–oxygen ignition in shock tubes. Combust Flame. 2014;161:1-15. |

| [11] | Dean AM, Steiner DC, Wang EE. A shock tube study of the H2/O2/CO/Ar and H2/N2O/CO/Ar systems: Measurement of the rate constant for H+ N2O= N2+ OH. Combust Flame. 1978;32:73–83. |

| [12] | Golden DM. Yet another look at the reaction CH3+ H+ M= CH4+ M. Int J Chem Kinet. 2008;40:310-9. |

| [13] | Troe J, Ushakov VG. The dissociation/recombination reaction CH4(+M)⇔ CH3+H (+M): A case study for unimolecular rate theory. J Chem Phys. 2012;136:214309. |

| [14] | Golden DM. What, methane again?!." Int J Chem Kinet. 2013; 45:213-20. |

| [15] | Sheen DA, Wang H. The method of uncertainty quantification and minimization using polynomial chaos expansions. Combust Flame. 2011;158:2358-74. |

| [16] | Lam KY, Davidson DF, Hanson RK. A shock tube study of H2+ OH → H2O+ H using OH laser absorption. Int J Chem Kinet. 2013;45:363-73. |

| [17] | Hong Z, Davidson DF, Barbour EA, Hanson RK. A new shock tube study of the H+ O2→ OH+ O reaction rate using tunable diode laser absorption of H2O near 2.5 μm. Proc Combust Inst. 2011;33:309-16. |

| [18] | Davis SG, Joshi AV, Wang H, Egolfopoulos F. An optimized kinetic model of H2/CO combustion. Proc Combust Inst. 2005;30:1283-92. |

| [19] | Stallcop JR, Partridge H, Levin E. Effective potential energies and transport cross sections for atom-molecule interactions of nitrogen and oxygen. Phys Rev A. 2001;64:042722. |

| [20] | Stallcop JR, Partridge H, Walch SP, Levin E. H–N2 interaction energies, transport cross sections, and collision integrals. J Chem Phys. 1992;97:3431-6. |

| [21] | Stallcop JR, Partridge H, Levin E. Effective potential energies and transport cross sections for interactions of hydrogen and nitrogen. Phys Rev A. 2000;62:062709. |

| [22] | Stallcop JR, Levin E, Partridge H. Transport properties of hydrogen. J Thermophys Heat Transfer. 1998;12:514-9. |

| [23] | Middha P, Yang B, Wang H. A first-principle calculation of the binary diffusion coefficients pertinent to kinetic modeling of hydrogen/oxygen/helium flames. Proc Combust Inst. 2002;29:1361-9. |

| [24] | Middha P, Wang H. First-principle calculation for the high-temperature diffusion coefficients of small pairs: The H-Ar case. Combust Theor Model. 2005;9:353-63. |

| [25] | Dagdigian, PJ. Combustion simulations with accurate transport properties for reactive intermediates. Combust Flame 2015; 162:2480-6. |

| [26] | Dagdigian PJ, Alexander MH. Exact quantum scattering calculation of transport properties for free radicals: OH(X2π–helium. J Chem Phys 2012; 137:09430. |

| [27] | Dagdigian PJ, Alexander MH. Exact quantum scattering calculation of transport properties for the H2O–H system. J Chem Phys 2013;139:19430. |

| [28] | Dagdigian PJ, Alexander MH. Transport properties for systems with deep potential wells: H+O2. J Phys Chem A 2014;118: 11935-42. |