Genetic variation within species is the ultimate driver of evolution and

phenotypic variation. Most of our work uses statistical and computational

methods to study aspects of genetic variation in human genetics and in evolutionary biology.

We often work on problems where we need to tackle new kinds of genomic data or new types of questions. Thus, a central part of our work involves developing appropriate statistical and computational approaches that can yield new insights into modern genome-scale data sets. Some of our main research interests are described below, with representative references.

At present much of our work focuses on next-generation approaches to integrating genetic associations with single-cell omics data, especially from perturb-seq and OPS.

GWAS/rare variant association methods provide a unique tool in human biology, as they can provide evidence for causal relationships from variants/genes to traits. However, they are generally difficult to interpret. Meanwhile, new perturbation approaches allow us to measure causal effects of genes in cells (and potentially tissues/organoids) at genome scale, albeit while introducing many analytical challenges. We aim to create the building blocks for new causal models that link together traditional GWAS with new perturbation tools. One main area of application is in T cells/immune traits, with Alex Marson's lab. Recent representative papers include: Ota et al 2025; Spence et al 2024; Zeng et al 2024; Freimer et al 2022.

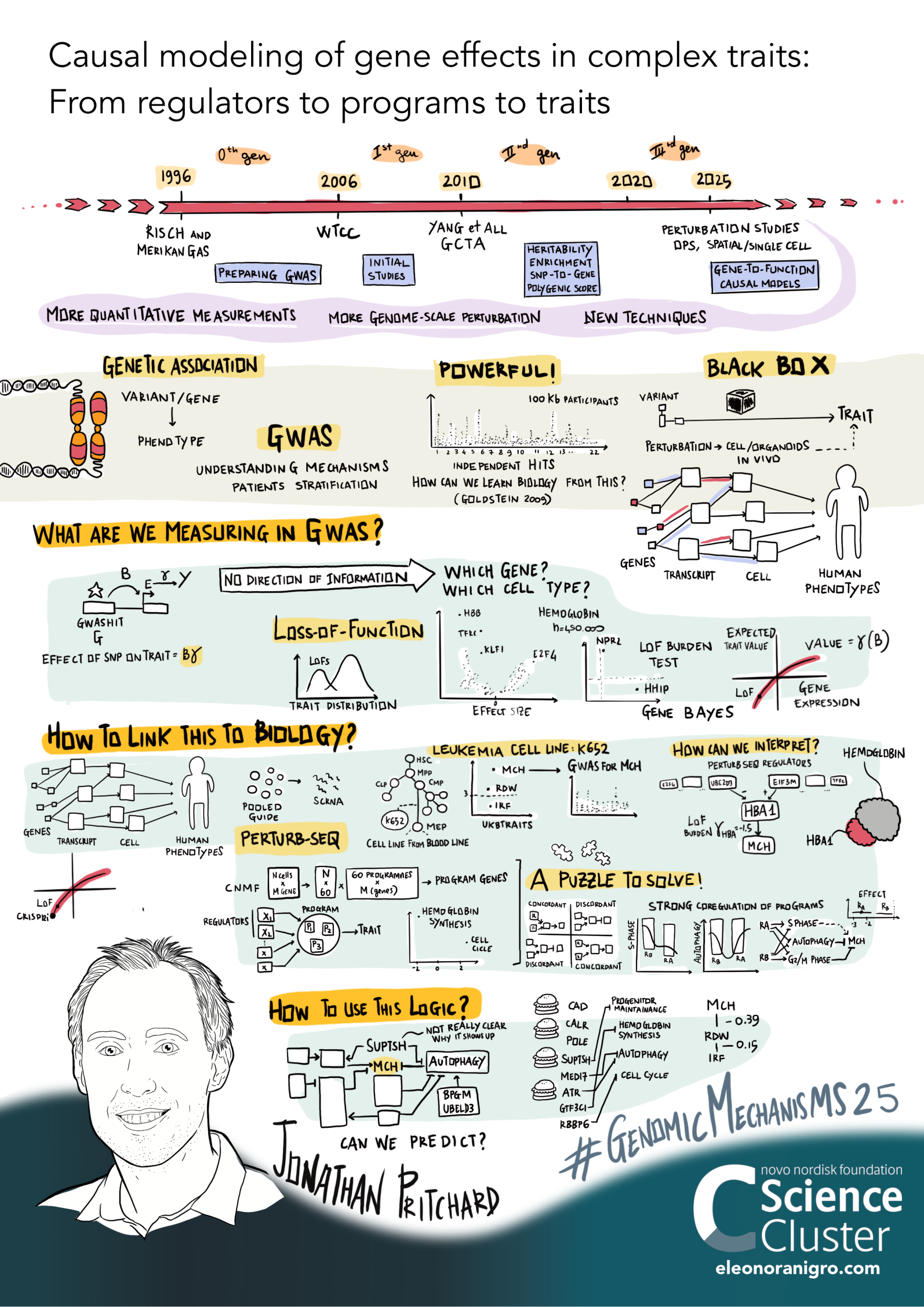

Here's a graphical overview of this work that

Eleanora Nigro drew based on a recent lab talk:

One prediction of the model is that anywhere from 70% to nearly 100% of the heritability for a complex trait (depending on the covariance of core genes) is due to weak trans effects mediated via peripheral genes (Liu et al, 2019).

Trans Effects on Gene Expression Can Drive Omnigenic Inheritance. Liu et al. 2019 Cell 177(40):1022-1034 [PDF]

In follow-up work we are exploring the architecture of a variety of model traits that can illustrate general principles of trait architecture. The first of these papers focuses on studying the nature of core genes, and how much these contribute to heritability. Meanwhile, important work from other groups has shown that in at least some cases polygenic risk is mediated via core genes: [link], [link].

GWAS of three molecular traits highlights core genes and pathways alongside a highly polygenic background. Sinnott-Armstrong et al. 2021 eLife. 10:e58615 [PDF]

And an important new focus relates to experimental measurement, inference, and theoretical modeling of gene regulatory networks, motivated by the prediction that most trait heritability flows through trans effects. Stay tuned in this space.

Starting in 2008 our lab initiated a primary focus to understand the primary mechanisms by which variation impacts expression, and to predict which variants have regulatory activity. Working with Yoav Gilad's lab, our main approach was to perform QTL mapping of a large number of functional genomics phenotypes in the same panel of cell lines with known genomes (75 Yoruba lymphoblastoid cell lines).

More recently, our main focus has turned to understanding trans-regulation through gene regulatory networks. This is motivated in part by the inference that most heritability for complex traits is mediated via trans-regulation. At present, methods for studying trans-regulation lag far behind the methods for studying and interpreting cis-regulation; however this is an area where modern CRISPR-based perturbations are starting to make key contributions.

Systematic discovery and perturbation of regulatory genes in human T cells reveals the architecture of immune networks. Freimer et al 2021. bioRxiv [PDF]

Landscape of stimulation-responsive chromatin across diverse human immune cells. Calderon et al 2019. Nature Genetics 51(10):1494-1505 [PDF]

Annotation-free quantification of RNA splicing using LeafCutter. Li et al 2018. Nature Genetics 50(1):151-158. [PDF]

RNA splicing is a primary link between genetic variation and disease. Li et al 2016. Science. 352:600-4. [PDF]

WASP: allele-specific software for robust molecular quantitative trait locus discovery. van de Geijn et al 2015. Nature Methods. 12:1061-3. [PDF]

Impact of regulatory variation from RNA to protein. Battle et al 2015. Science 347:664-7. [PDF]

Identification of Genetic Variants That Affect Histone Modifications in Human Cells. McVicker et al 2013. Science 342:747-9. [PDF]

Primate Transcript and Protein Expression Levels Evolve under Compensatory Selection Pressures. Khan et al 2013. Science 342:1100-4. [PDF]

DNaseI sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Degner et al 2012. Nature 482:390-4. [PDF]

Dissecting the regulatory architecture of gene expression QTLs. Gaffney et al 2012. Genome Biology 13(1):R7. [PDF]

Understanding mechanisms underlying human gene expression variation with RNA sequencing. Pickrell et al 2010. Nature 464:768-72. [PDF]

One class of methods that we have developed makes use of data from SNPs or other markers to study population structure and ancestry of a species. The Pritchard-Stephens-Donnelly algorithm was implemented in the program Structure algorithm. Structure views a sample of individuals as (potentially) representing a mixture from different genetic populations. It uses the marker data to infer both the overall genetic structure and the ancestry of individuals.

This model has been very widely used in a wide variety of contexts, and the original paper has been highly cited [historical perspective by John Novembre 2016]. The Structure ancestry model underlies the ancestry reports used by 23andMe and Ancestry.com. The software is also widely used for applications in conservation biology and ecology. Closely related models - developed a couple of years later by David Blei and colleagues - have been very influential in the topic modeling literature.

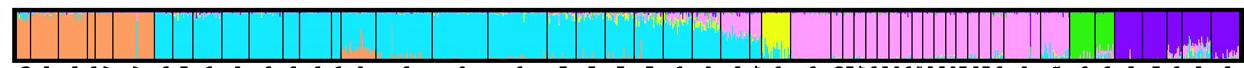

The image below is the first Structure ancestry plot, made by Noah Rosenberg and Jonathan in 2002. This shows clustering results for 1056 humans from 52 globally distributed populations.

In other early work, we built on key papers from Simon Tavare and Gunther Weiss to develop the first application of Approximate Bayesian Computation, in this case to estimate human demography from Y chromosome data [PDF].

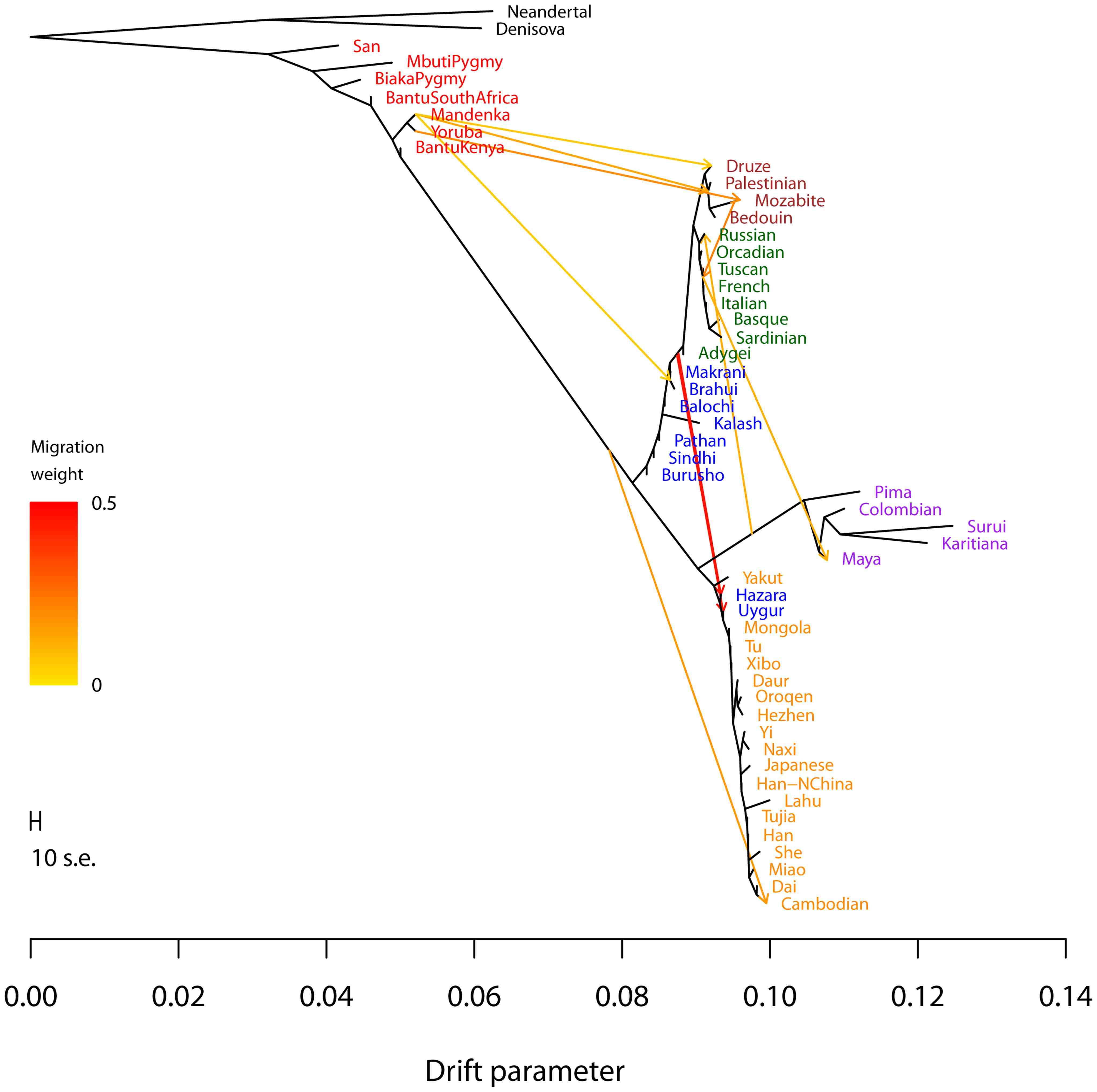

With Joe Pickrell, we developed the TreeMix algorithm for inferring the relationships among modern populations, while allowing for pulses of gene flow between different clades in the tree (as illustrated at right).

Our current work in this area has moved into using ancient DNA approaches to study changes in population ancestry over time, as well as adaptive shifts. In collaboration with Ron Pinhasi (Vienna) and Alfredo Coppa (Rome) we are conducting studies of ancient DNA in Rome and other regions of the Mediterranean. We are also interested in methods development for studying population genetics in temporal and spatial data.

Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean. Antonio et al 2019. Science. 366:708-714. [PDF] [Short Video] [Science news]

fastSTRUCTURE: variational inference of population structure in large SNP data sets. Raj et al 2014. Genetics 197:573-89. [PDF]

Inference of population splits and mixtures from genome-wide allele frequency data. Pickrell and Pritchard 2012. PLoS Genetics 8:e1002967 [PDF] [Software]

Sequencing and Analysis of Neanderthal Genomic DNA. Noonan et al 2006. Science 314:1113-1118. [PDF]

The genetic structure of human populations. Rosenberg et al 2002. Science 298: 2381-2385. [PDF]

Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Pritchard et al 2000. Genetics 155: 945-959. [PDF], [Software]

Population growth of human Y chromosomes: a study of Y chromosome microsatellites. Pritchard et al 1999. Mol. Biol. Evol., 16:1791-1798. [PDF],

In our early work on this problem our goal was to identify the strongest signals of selective sweeps in the genome (Voight et al 2006).

Instead we have proposed that most adaptation likely occurs through a process of "polygenic adapation" in which small allele frequencies at large numbers of quantitative trait loci allow very rapid phenotypic adaptation but are difficult to detect by standard tests. Consequently we are very interested in approaches for studying polygenic adaptation from modern and ancient DNA data. One example of this work was presented in Yair Field's 2016 paper using our SDS statistic to infer recent changes in allele frequencies. However, this work remains challenging due to concerns about subtle population structure confounding in GWAS.

In other ongoing work we are also studying models of stabilizing selection in complex trait, as well as balancing selection in MHC.

Reduced signal for polygenic adaptation of height in UK Biobank. Berg et al 2019. Elife. 8:e39725 [PDF]

Evidence of weak selective constraint on human gene expression. Glassberg et al 2019. Genetics. 211(2):757-772 [PDF]

Detection of human adaptation during the past 2000 years. Field et al 2016. Science 354:760-764. [PDF]

The deleterious mutation load is insensitive to recent population history. Simons et al 2014. Nature Genetics 46:220-4. [PDF]

The genetics of human adaptation: hard sweeps, soft sweeps, and polygenic adaptation. Pritchard et al 2010 Current Biology. 20:R208-15. [PDF]

How we are evolving. Pritchard 2010 Scientific American. 301(10):41-47. [link]

The role of geography in human adaptation. Coop et al 2009 PLoS Genetics 5:e1000500. [PDF]

A Map of Recent Positive Selection in the Human Genome. Voight, et al 2006. PLoS Biol 4(3): e72 [PDF] [2013 Perspective on this work]

One area of interest has been in understanding linkage disequilibrium and recombination (much of this in collaboration with Molly Przeworski and Graham Coop), including providing evidence for variation in hotspot usage across individuals (now known to be due to variation at PRDM9).

When Don Conrad was in the lab he provided one of the early genome-wide surveys of deletion polymormisms, when it was first becoming clear that copy number variation is an important aspect of genome variation (see figure at right).

We also helped to introduce the idea of using genotype data to detect and controlling for the confounding effects of population structure in association mapping. More broadly we have been interested in population genetic models of complex traits, including work on the role of rare variants in disease.

A wild-derived antimutator drives germline mutation spectrum differences in a genetically diverse murine family. Sasani et al 2021. bioRxiv 2021.03.12.435196 [PDF]

Rapid evolution of the human mutation spectrum. Harris and Pritchard 2017. Elife. 6: e24284 [PDF]

Coregulation of tandem duplicate genes slows evolution of subfunctionalization in mammals. Lan and Pritchard 2016 Science. 352:1009-13. [PDF]

Genetic variation in MHC proteins is associated with T cell receptor expression biases. Sharon et al 2016. Nature Genetics. 48:995-1002 [PDF]

High-Resolution Mapping of Crossovers Reveals Extensive Variation in Fine-Scale Recombination Patterns Among Humans. Coop et al 2008. Science 319: 1395-1398. [PDF]

A high-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Conrad et al 2006. Nature Genetics 38:75-81. [PDF]

Clonal origin and evolution of a transmissible cancer. Murgia, et al 2006. Cell 126:477-87. [PDF]

Linkage disequilibrium in humans: models and data. Pritchard and Przeworski 2001. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69:1-14 [PDF]

Use of unlinked genetic markers to detect population stratification in association studies. Pritchard and Rosenberg 1999. Am. J. of Hum. Gen. 65: 220-228. [PDF]