Written by John Louie and Michael Chang, with modifications by Nick Troccoli and Lisa Yan

Introduction

Your coworker suggests you use the function below as a "safer" free function that prevents accidentally using a freed pointer.

void free_and_null(void *ptr) {

free(ptr);

ptr = NULL

}

Will this function correctly free the client's pointer? Will it correctly set it to NULL? Explain.

It will free it, but it will not set it to NULL, as it only sets free_and_null's own copy of the pointer to NULL. You would need to pass a pointer to the pointer to NULL it out as well.

Lecture Review

The key goal for lab3 is to get practice working with pointers, arrays and dynamic memory. Here are key concepts relevant to this week's lab:

- when passing parameters, C always passes a copy of whatever parameter is passed.

- to change a value and have its changes persist outside of a function, we must pass a pointer to the value.

- when passing arrays as parameters, we always pass them as a pointer to the first element.

- arrays of pointers are arrays containing pointers to each element (it does not store the elements themselves; e.g. an array of strings stores pointers to their first characters, not the characters themselves)

- pointer arithmetic works in units of the size of the pointee type. E.g. +1 for an

int *means advance one int, so 4 bytes. - the stack is the area of memory where local variables and parameters are stored. Each function call has its own stack frame, which is created when the call starts, and goes away when the function ends. The stack grows downwards and shrinks upwards.

- the heap is a separate area of memory below the stack that stores memory we manually allocate. This is beneficial if we want to store data that persists beyond a single function call. However, we must clean up the memory when we are done, because C no longer knows when we are done with it, as it does with stack memory.

- We use the memory functions

malloc/calloc/etc. to request memory on the heap. We request a number of bytes, and the functions return a pointer to the newly-allocated memory. - To clean up memory when we are done, we use the

freefunction and pass in a pointer to the memory we would like to free. - Heap memory is resizable; we can request a change of size by using

realloc, and passing in the original heap allocation and the new size we would like. - The stack is good because of easy cleanup, fast allocation, and type safety. The heap is good because of its large size, ability to resize allocations, and its persistence beyond 1 function's stack frame.

Solutions

1) GDB: Pointers and Arrays (15 minutes + 10 min all-lab discussion)

a) Arrays vs. Pointers

Q1: For each expression below with local variable arr, what should the result of the expression should be? Evaluate each in gdb to confirm that your understanding is correct.

A1: Answers shown below, to the right of each line:

(gdb) p *arr (0)

(gdb) p arr[1] (10)

(gdb) p &arr[1] (address of index-1 element)

(gdb) p *(arr + 2) (20)

(gdb) p &arr[3] - &arr[1] (2)

(gdb) p sizeof(arr) (24)

(gdb) p arr = arr + 1 (Invalid cast.)

Q2: What is reported for the size of an array? the size of a pointer? The last one is the trickiest to understand. Why is it allowable to assign to ptr but not arr?

A2: The size of the array is 24, but the size of a pointer is 8. We can assign a pointer to point to something else because we can change the address that it stores, but we cannot assign an array to something else because it's not storing an address, but rather the elements themselves. In summary, everything is the same between arrays and pointers except sizeof and assignment. (However, once outside the scope of the declaring function, arrays and pointers behave identically.)

Q3: &arr[0] stores the same address as &ptr[0], but &arr isn't the same address as &ptr. Why not? NOTE: this discrepancy is key - it will almost certainly come up on future assignments!

A3: This discrepancy comes from the fact that you can't get the address of array like that because it is not a pointer, and there is no memory location that stores this address like for a pointer. Instead, it evaluates to the base address of the array. & on a pointer works as expected. (Also, even though gdb prints &arr differently, the & still has no effect).

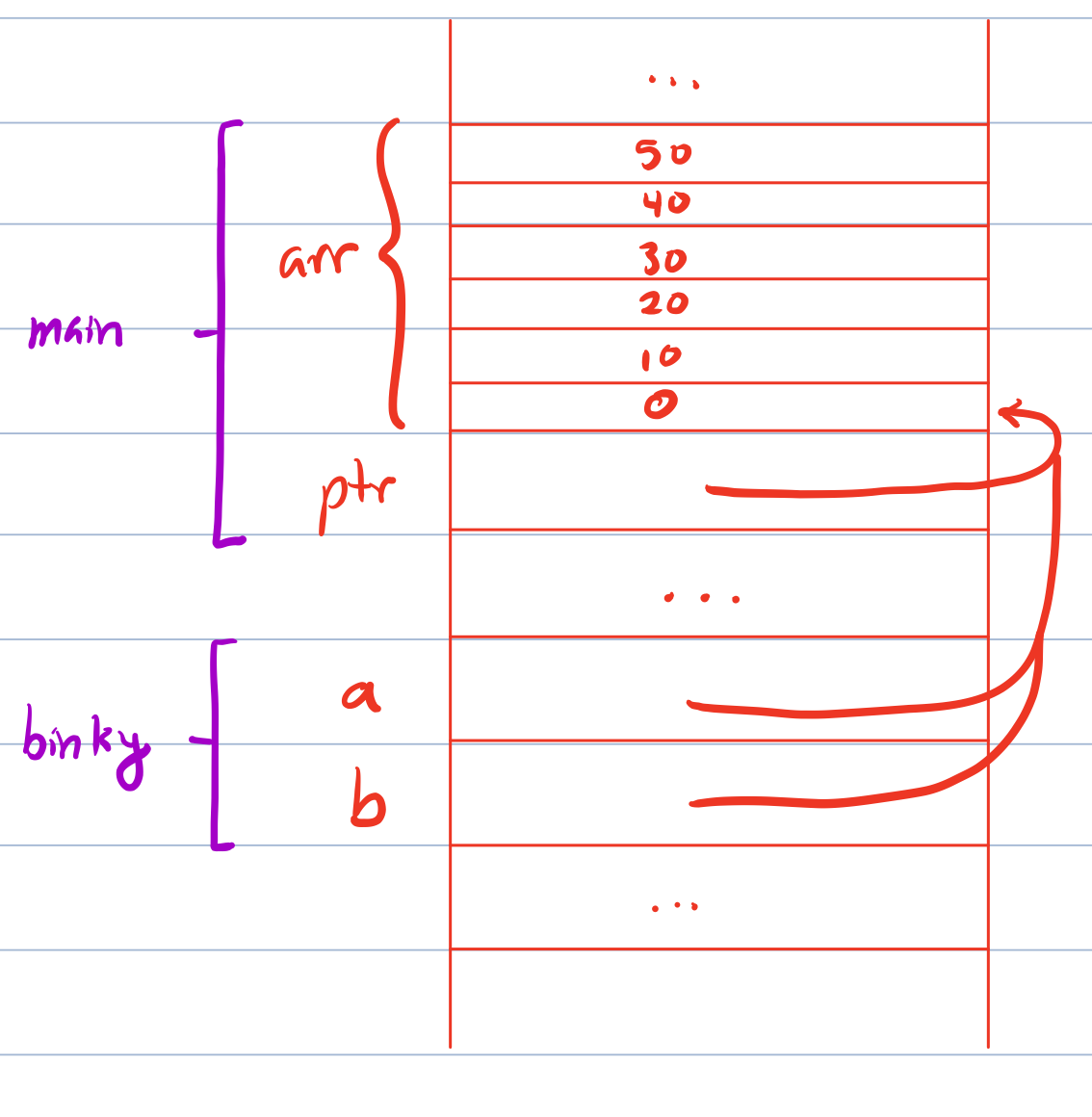

Q4: Use the gdb step command to advance into the call binky(arr, ptr). step is like next, but instead of executing the entire line and moving to the next line, it steps into the execution of the line. Once inside binky, use info args to see the values of the two parameters. They are identical! What happens in parameter passing to make this so?

A4: Once outside the scope of the declaring function, arrays and pointers behave identically because arrays "decay to" pointers. Writing int param[] vs int *param has zero functional effect. Here is a memory diagram of binky to help visualize - drawing memory diagrams are a great way to better understand the behavior of programs, we highly recommend sketching things out to confirm your understanding!

b) Pointers, double pointers, and gdb stack frames in winky()

Q5: Step through change_char and examine the state before and after each line. Use info args to show the inner frame and up and info locals to show what's happening in the outer frame. Carefully observe the effect of each assignment statement. Can you explain the behavior of each line?

A5: *s = 'j'; does change the string from winky because we are going to the memory location passed in and changing what's there, while s = "Leland"; does not change the string from winky because it is changing the function's own copy of s. We could also pass word instead of pw, because because both would be passed as pointers to the first element.

Q6: Step through the call to change_ptr and make the same observations. Which of the assignment statements had a persistent effect in winky, and which did not? Why?

A6: The first two lines both change the data from winky because they are (1) going to the memory location passed in and then dereferencing again to change the character at that location, and (2) going to the memory location passed in and changing what's there. However, the last line does not change the data from winky because it is changing the function's own copy of p_str. We could also not pass in &word instead of &pw because &word deceptively still gives the address of the first array element, and is therefore not a pointer to the pointer to the first array element (& on an array does nothing).

Here are some other tips / notes:

- Remember that when gdb shows a line, it has not yet executed that line.

- Everything in C is passed by value. If you want to change "x", you need to pass "pointer to x". If x is a

char, pass achar *; if x is achar *, pass achar **.

2) Valgrind (20 minutes + 10 min all-lab discussion)

One key takeaway from this exercise; sometimes, valgrind reports show issues within library functions, but library functions rarely (if ever) cause errors. Instead, the problem is most definitely due to invalid arguments. Leaks are also most definitely due to not freeing memory allocated by those functions, rather than an issue with the function itself.

Memory Errors

Error 1: writing past the end of heap-allocated memory

This function allocates 8 bytes on the heap, but allows the caller to specify more than that to copy in. This works fine for a while, even with a little overflow, but eventually it runs into heap manager metadata, and libc error checking will catch it. Here's what the Valgrind report might look like when running ./buggy 1, which tries to copy "Stanford" (total of 9 bytes) in - this correctly detects we are writing 1 byte to a location that is not part of the allocated memory space:

myth$ valgrind ./buggy 1

==3612603== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==3612603== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==3612603== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==3612603== Command: ./buggy 1

==3612603==

--- Making error 1: write past end of heap-allocated memory

Copying string 'Stanford' (9 bytes total) to destination heap-allocated 8 bytes.

==3612603== Invalid write of size 1

==3612603== at 0x483F0BE: strcpy (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==3612603== by 0x109283: make_error_1 (buggy.c:25)

==3612603== by 0x1093E3: main (buggy.c:64)

==3612603== Address 0x4a5f488 is 0 bytes after a block of size 8 alloc'd

==3612603== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==3612603== by 0x1091EA: make_error_1 (buggy.c:17)

==3612603== by 0x1093E3: main (buggy.c:64)

==3612603==

==3612603==

==3612603== HEAP SUMMARY:

==3612603== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==3612603== total heap usage: 3 allocs, 3 frees, 1,040 bytes allocated

==3612603==

==3612603== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==3612603==

==3612603== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==3612603== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

Error 2: accessing freed heap memory

Q7: Review the code to see what the error is. What is the error?

A7: This function allocates memory for a string, frees it, and then tries to print it out, which is a use-after-free error. Valgrind properly detects many invalid reads of freed memory, which no longer belong to the program.

Q8: Run it (e.g. ./buggy 2). Is there an observable result of the error?

A8: Maybe not! The program may run fine, though the string printed out might be empty (perhaps the memory was already reused by the heap to store something else).

Q9: Run it under Valgrind. What is the terminology that the Valgrind report uses and how does it relate back to the root cause? Observe how the behavior of the program when run in Valgrind is different than when run outside - a memory error can result in undefined behavior that may vary!

A9: See below for what the valgrind report might look like when running ./buggy 2. Valgrind outputs "invalid read of size X" errors if our code reads from memory that we shouldn't be reading from. It shows us where that invalid read is happening in our code (here, inside of printf - though it is not due to an issue with printf's implementation, but rather an issue with what we are printing out) and where that accessed memory is ("address X is X bytes inside a block of size 14 free'd"). This means it is the first byte of a 14-byte block we have freed. It also shows us where it was previously freed. Neat! Valgrind properly detects many invalid reads of freed memory, which no longer belong to the program.

myth$ valgrind ./buggy 2

==898626== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==898626== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==898626== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==898626== Command: ./buggy 2

==898626==

--- Making error 2: access heap memory that has been freed

==898626== Invalid read of size 1

==898626== at 0x483EF46: strlen (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x48E5E94: __vfprintf_internal (vfprintf-internal.c:1688)

==898626== by 0x48CEEBE: printf (printf.c:33)

==898626== by 0x1092CC: make_error_2 (buggy.c:34)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Address 0x4a5f480 is 0 bytes inside a block of size 14 free'd

==898626== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x1092B4: make_error_2 (buggy.c:31)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Block was alloc'd at

==898626== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==898626== by 0x10927E: make_error_2 (buggy.c:29)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626==

==898626== Invalid read of size 1

==898626== at 0x483EF54: strlen (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x48E5E94: __vfprintf_internal (vfprintf-internal.c:1688)

==898626== by 0x48CEEBE: printf (printf.c:33)

==898626== by 0x1092CC: make_error_2 (buggy.c:34)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Address 0x4a5f481 is 1 bytes inside a block of size 14 free'd

==898626== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x1092B4: make_error_2 (buggy.c:31)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Block was alloc'd at

==898626== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==898626== by 0x10927E: make_error_2 (buggy.c:29)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626==

==898626== Invalid read of size 1

==898626== at 0x48FC88C: _IO_new_file_xsputn (fileops.c:1219)

==898626== by 0x48FC88C: _IO_file_xsputn@@GLIBC_2.2.5 (fileops.c:1197)

==898626== by 0x48E427B: __vfprintf_internal (vfprintf-internal.c:1688)

==898626== by 0x48CEEBE: printf (printf.c:33)

==898626== by 0x1092CC: make_error_2 (buggy.c:34)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Address 0x4a5f48c is 12 bytes inside a block of size 14 free'd

==898626== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x1092B4: make_error_2 (buggy.c:31)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Block was alloc'd at

==898626== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==898626== by 0x10927E: make_error_2 (buggy.c:29)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626==

==898626== Invalid read of size 1

==898626== at 0x48436E0: mempcpy (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x48FC7B1: _IO_new_file_xsputn (fileops.c:1236)

==898626== by 0x48FC7B1: _IO_file_xsputn@@GLIBC_2.2.5 (fileops.c:1197)

==898626== by 0x48E427B: __vfprintf_internal (vfprintf-internal.c:1688)

==898626== by 0x48CEEBE: printf (printf.c:33)

==898626== by 0x1092CC: make_error_2 (buggy.c:34)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Address 0x4a5f480 is 0 bytes inside a block of size 14 free'd

==898626== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x1092B4: make_error_2 (buggy.c:31)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Block was alloc'd at

==898626== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==898626== by 0x10927E: make_error_2 (buggy.c:29)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626==

==898626== Invalid read of size 1

==898626== at 0x48436EE: mempcpy (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x48FC7B1: _IO_new_file_xsputn (fileops.c:1236)

==898626== by 0x48FC7B1: _IO_file_xsputn@@GLIBC_2.2.5 (fileops.c:1197)

==898626== by 0x48E427B: __vfprintf_internal (vfprintf-internal.c:1688)

==898626== by 0x48CEEBE: printf (printf.c:33)

==898626== by 0x1092CC: make_error_2 (buggy.c:34)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Address 0x4a5f482 is 2 bytes inside a block of size 14 free'd

==898626== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x1092B4: make_error_2 (buggy.c:31)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626== Block was alloc'd at

==898626== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898626== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==898626== by 0x10927E: make_error_2 (buggy.c:29)

==898626== by 0x1093B5: main (buggy.c:61)

==898626==

Freed memory contains 'Jane Stanford'

==898626==

==898626== HEAP SUMMARY:

==898626== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==898626== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 2 frees, 1,038 bytes allocated

==898626==

==898626== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==898626==

==898626== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==898626== ERROR SUMMARY: 40 errors from 5 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

(Optional) Error 3: freeing allocated memory twice

This function allocates memory on the heap for a string, creates another pointer to the same memory, and then frees both pointers. This is a common issue; even though you may have multiple pointers to the memory, you should only free it once, because there is still only one block of memory allocated. This error will crash the program with a cryptic error message. Here's what the valgrind report might look like when running ./buggy 3:

myth$ valgrind ./buggy 3

==898688== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==898688== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==898688== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==898688== Command: ./buggy 3

==898688==

--- Making error 3: double free heap memory

==898688== Invalid free() / delete / delete[] / realloc()

==898688== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898688== by 0x109341: make_error_3 (buggy.c:51)

==898688== by 0x1093C7: main (buggy.c:63)

==898688== Address 0x4a5f480 is 0 bytes inside a block of size 19 free'd

==898688== at 0x483CA3F: free (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898688== by 0x10932D: make_error_3 (buggy.c:47)

==898688== by 0x1093C7: main (buggy.c:63)

==898688== Block was alloc'd at

==898688== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898688== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==898688== by 0x1092EF: make_error_3 (buggy.c:41)

==898688== by 0x1093C7: main (buggy.c:63)

==898688==

==898688==

==898688== HEAP SUMMARY:

==898688== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==898688== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 3 frees, 1,043 bytes allocated

==898688==

==898688== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==898688==

==898688== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==898688== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

Valgrind properly detects the invalid free!

Memory Leaks

Note that none of these leaks impact the execution of the program, but should be fixed regardless. All the valgrind reports below are run with --leak-check=full and --show-leak-kinds=all; make sure you include these flags when you run valgrind to get as much information as possible about leaks.

Leak 1: function returning without freeing memory

This function allocates 8 bytes, and then returns without freeing it. Here's what a valgrind report might look like:

myth$ valgrind --leak-check=full --show-leak-kinds=all ./leaks 1

==898956== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==898956== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==898956== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==898956== Command: ./leaks 1

==898956==

--- Leaking memory 1: allocating memory and then function finishes

==898956==

==898956== HEAP SUMMARY:

==898956== in use at exit: 8 bytes in 1 blocks

==898956== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 1 frees, 1,032 bytes allocated

==898956==

==898956== 8 bytes in 1 blocks are definitely lost in loss record 1 of 1

==898956== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==898956== by 0x109196: make_leak_1 (leaks.c:15)

==898956== by 0x10923B: main (leaks.c:38)

==898956==

==898956== LEAK SUMMARY:

==898956== definitely lost: 8 bytes in 1 blocks

==898956== indirectly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==898956== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==898956== still reachable: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==898956== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==898956==

==898956== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==898956== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

You can see the 8 bytes that is "definitely lost", as well as an indicator of where that memory was originally allocated from. Helpful! For a summary of what the different terms in the LEAK SUMMARY mean, check out the Valgrind guide.

Leak 2: function allocates memory but then reassigns pointer

Q10: Review the code to see what the leak is, and then run it (e.g. ./leaks 2). Notice how the program always runs fine. What is the issue with the code?

A10: This function leaks memory by allocating memory, but then reassigning the pointer and thus losing access to the allocated memory.

Q11: Run it under Valgrind. What is the terminology that the Valgrind report uses and how does it relate back to the root cause?

A11: Valgrind says "X bytes in X blocks are definitely lost", and shows a trace to where the lost memory was initially allocated (in this case, malloc, which was called from strdup, which was called from make_leak_2). It shows us 14 bytes were lost, which is the size of the space requested to store the string "Hello, world!" plus a null terminator. See below for what a valgrind report might look like. Valgrind catches the leak and points to its original allocation in strdup.

myth$ valgrind --leak-check=full --show-leak-kinds=all ./leaks 2

==899011== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==899011== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==899011== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==899011== Command: ./leaks 2

==899011==

--- Leaking memory 2: allocating memory, but then losing pointer to it

Stack string

==899011==

==899011== HEAP SUMMARY:

==899011== in use at exit: 14 bytes in 1 blocks

==899011== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 1 frees, 1,038 bytes allocated

==899011==

==899011== 14 bytes in 1 blocks are definitely lost in loss record 1 of 1

==899011== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==899011== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==899011== by 0x1091BD: make_leak_2 (leaks.c:21)

==899011== by 0x10924D: main (leaks.c:40)

==899011==

==899011== LEAK SUMMARY:

==899011== definitely lost: 14 bytes in 1 blocks

==899011== indirectly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899011== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899011== still reachable: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899011== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899011==

==899011== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==899011== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

(Optional) Leak 3: function allocates memory and returns its address, but caller does not free

This function itself does not leak memory, but its caller fails to free it, and thus the memory is still leaked. Here's what a valgrind report might look like:

myth$ valgrind --leak-check=full --show-leak-kinds=all ./leaks 3

==899054== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==899054== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==899054== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==899054== Command: ./leaks 3

==899054==

--- Leaking memory 3: allocating memory, returning address, but caller doesn't free

==899054==

==899054== HEAP SUMMARY:

==899054== in use at exit: 14 bytes in 1 blocks

==899054== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 1 frees, 1,038 bytes allocated

==899054==

==899054== 14 bytes in 1 blocks are definitely lost in loss record 1 of 1

==899054== at 0x483B7F3: malloc (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/valgrind/vgpreload_memcheck-amd64-linux.so)

==899054== by 0x490C50E: strdup (strdup.c:42)

==899054== by 0x1091F7: make_leak_3 (leaks.c:31)

==899054== by 0x10925F: main (leaks.c:42)

==899054==

==899054== LEAK SUMMARY:

==899054== definitely lost: 14 bytes in 1 blocks

==899054== indirectly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899054== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899054== still reachable: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899054== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==899054==

==899054== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==899054== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

Again, the leak is caught, and it reports the trace all the way from main, where it was ultimately lost.

Note: the total heap usage includes more than just your explicit allocations. For example, other functions, like strdup, may allocate/free memory internally as well!

3) Debugging (20 minutes + 5 min all-lab discussion)

The goal for this problem is to work through and ultimately hone in on the bug, with a process like the following: "I replicated with test case X, I used GDB to narrow down the crash to line X or function X, and then poked around to find that the bug was X". Here's how we can use the debugging checklist to do this:

- Observe the bug. Run

tools/sanitycheck custom_teststo see the provided buggy test case. - Create a reproducible input. There are many different possible approaches; ideally the test case will be two words, the second of which starts with e.g. a number.

- Narrow the search space. GDB should report that the program crashes on line 95 inside of

pig_cat.backtracecan give us more information about where exactly in our program execution it happened. - Analyze. A segmentation fault means we are accessing memory that doesn't belong to us. If a segfault occurs on a line of code, we can try inspecting parameter values to any functions called there, or the values of any pointers being dereferenced. Here, from printing out values, it seems the issue is that

pig_wordisNULL, which isn't a valid parameter value tostrlen, sincestrlenwill go to that memory location to count up characters. It seems that the programmer assumed it might be the empty string, but notNULL. If we breakpoint at the start ofpig_catand step through the function from the start, printing out values shows thatpig_latinreturnsNULLfor invalid strings, and the first time on line 83 we check correctly, but the second time we do not. - Devise and run experiments. One approach is to try another test case and step through to confirm our suspicions about why it doesn't work.

- Modify code to squash the bug. The fix is to change the statement to instead check if

pig_wordisNULL.

Checkoff Answers

- If

arris a stack array, and pointer variableptr = arr,&arr[0]stores the same address as&ptr[0], but&arrisn't the same address as&ptr. Why not? You can't get the address of array like that because it is not a pointer, and there is no memory location that stores this address like for a pointer. Instead, it evaluates to the base address of the array. - Often the backtrace for a Valgrind-reported error or leak will show a trace to somewhere within a library function such as

strcpyorstrdup. It may be tempting to conclude that the problem is in the library, and is not yours to fix. Explain why this is reasoning is false. Library functions rarely (if ever) cause errors; instead, the problem is most definitely due to invalid arguments. Leaks are also most definitely due to not freeing memory allocated by those functions, rather than an issue with the function itself. - Briefly explain your process for debugging the Pig Latin program and how you followed the provided checklist. Depends on the approach! For instance, something like "I replicated with test case X, I used GDB to narrow down the crash to line X or function X, and then poked around to find that the bug was X".

Additional Thought Questions

- If

ptris declared as anchar *, what is the effect ofptr++? What ifptris declared as aint *? Incrementing increments by the size of the pointee - so for achar *it increments by 1 byte, but for anint *4 bytes. - Although

&applied to the name of a stack-allocated array (e.g.&buffer) is a legal expression and has a defined meaning, it isn't really sensible. Explain why such use may indicate an error/misunderstanding on the part of the programmer. & on arrays is a no-op - it evaluates to the address of the first element of the array, which is what the array evaluates to already by default in pointer expressions. - The argument to malloc is

size_t(unsigned). Consider the erroneous callmalloc(-1), which seems to make no sense at all. The call compiles with nary a complaint -- why is it "ok"? What happens when it executes? The value is casted to a size_t and treated as a very large number! Running this shows that malloc returns NULL. - What is the purpose of the

reallocfunction? What happens if you attempt to realloc a non-malloc-ed pointer, such as a string constant? realloc lets us resize memory allocations. It is undefined behavior if we realloc an invalid value. - What is the difference between a memory error and a memory leak? The core cause of a memory error is accessing (reading or writing) memory that does not belong to you. For instance, if you create a string that is not null-terminated and call strlen() on it, this causes a memory error because it will cause strlen to search through memory that doesn’t belong to that string in search of a null terminator. The core cause of a memory leak is not freeing memory you have allocated on the heap. For instance, if you call malloc() or strdup(), you must free the return value of that function when you are done with it.

- Your coworker suggests you use the function below as a "safer" free function that prevents accidentally using a freed pointer. It will free it, but it will not set it to NULL, as it only sets

free_and_null's own copy of the pointer to NULL. You would need to pass a pointer to the pointer to NULL it out as well.

[Optional] Extra Problems

Heap Use Code Study: join

Q1: Is the size argument to realloc the number of additional bytes to add to the memory block, or the total number of bytes including any previously allocated part?

A1: It's the total number of bytes, including any previously-allocated part.

Q2: The variable result is initialized to strdup(strings[0]). Why does it make a copy instead of just assigning result = strings[0]?

A2: We are building up a new heap-allocated string, so we can't build on an existing string pointer - it may not be heap-allocated, for instance, and we need our own copy in memory.

Q3: What error is that warning trying to caution you against? A realloc call that doesn't catch its return value is never the right call.

A3: The compiler warns against an unused return value - this is bad for realloc because it may cause an immediate memory leak if the memory has been moved to a new location!

Heap Use Code Study: remove_first_occurrence

This function returns a heap-allocated copy of the provided string with the first instance of pattern (if any) removed.

Q1: What is the purpose of the library function strstr? What does it return?

A1: strstr searches for the first occurrence of pattern in text, and returns a pointer to the start of the match, or NULL if no match was found. It is used to locate the found match to remove, if any.

Q2: Lines 6-8 handle the case where there is no occurrence of pattern in text, i.e. nothing to remove. Why does the function return strdup(text) rather than just returning text?

A2: The function must always return a heap-allocated string, so it must use strdup to create a copy and return it. Otherwise, the client wouldn't know whether it needed to be freed later or not!

Q3: Line 10 subtracts two pointers. What is the result of subtracting two pointers? Here's a hint: if q = p + 3, then q - p => 3. How does the sizeof(pointee) affect the result of a subtraction?

A3: Pointer subtraction returns the number of places that differ between the two pointers, where a "place" is the size of a single element that the pointers point to. In this instance, subtracting on line 10 returns the number of characters difference between the pointers.

Q4: assert terminates the program if the passed-in expression is false. What is the check on line 13?

A4: This check is an important check to see if malloc returned NULL, indicating that there is no more heap memory. We assert here to crash the program if this occurs.

Q5: After line 17 executes, is the result string null-terminated? Why or why not?

A5: The string is not null terminated, because strncpy does not add a null-terminator if it is not explicitly copied over. This is ok, however, because the following line's call to strcpy does add a null terminator.

Q6: Your colleague proposes changing line 18 to instead: strcat(result, found + nremoved) claiming it will operate equivalently. You try it and it even seems to work. Is it equivalent? No, not quite... The code is just "getting lucky". In what way does it (wrongly) depend on the initial contents of newly allocated heap memory? How will the function break when that wrong assumption is not true?

A6: strcat assumes the string to concatenate to is null-terminated, so if it's not it may continue to walk the string until it finds one! However, heap memory here is likely initially zero, but may not be after the program has run for a while, so it may work, or it may not!

Code Study: calloc

Q1: What are lines 2-4 of the function doing? What would be the effect on the function's operation if these were removed?

A1: These functions check for overflow in the total amount of memory requested.

Q2: A colleague objects to the use of division on line 2 because division is more expensive than multiplication and it requires an extra check for a zero divisor. They propose changing it to if (nelems * elemsz > SIZE_MAX), claiming it will operate equivalently and more efficiently. Why won't this plan work?

A2: This approach may overflow, which is exactly the overflow we are trying to check for!

Q3: What is the purpose of line 7? What would be the effect on the function's operation if that test were removed and it always proceeded into the loop?

A3: This check sees if memory was in fact allocated. The loop would crash if the check was omitted, because the loop would try to dereference the NULL pointer.

Q4: This calculation is making an assumption about how many bytes malloc will actually reserve for a given requested size. What is that assumption? (This behavior is not a documented public feature and no client that was a true outsider should assume this, but calloc and malloc were authored by the same programmer, and thus calloc is being written by someone with firsthand knowledge of the malloc internals and acting as a privileged insider.)

A4: The assumption is that malloc actually reserves a multiple of 8 bytes. So if the requested amount is not a multiple of 8, malloc will round it up to the nearest multiple. Because of this, while it technically appears that the loop might run up to 7 bytes off at the end (e.g. if the requested size is 9), it's actually safe.

Q5: The initialization of the for loop on line 10 assigns wp = p, yet wp and p are not of the same declared type. Why is no typecast required here? Would the function behave any differently if you added the typecast wp = (long *)p?

A5: You can assign to/from a void * without casting. The cast here is optional and doesn't have any effect if included.

Q6: Imagine if line 8 instead declared char *wp with no other changes to the code. How would this change the function's behavior? What if the declaration was int *wp? What if the declaration were void *wp? For each, consider how the pointee type affects the operations wp++ and *wp = 0. What do you think is the motivation for the author's choice of long *?

A6: Changing the type will not impact correctness, but it will require more loop iterations because of the smaller type size; all the mathematical operations would change underlying behavior depending on the type. Filling memory in larger chunks is best, which is why long is the best choice here. However, void * would not work, because then you couldn't dereference wp.

Calloc Challenge

A good way to do this is to write a function to make a long containing copies of the desired pattern. This can be built up using bit operations by copying in the pattern, shifting by the width of the pattern, and then continuing until the entire long is filled in with copies of the pattern. Then, change the line that fills in 0s in calloc to fill in with the specified pattern instead. This could look something like this:

unsigned long create_fill_value(unsigned long pattern, int width) {

if (width == 0) {

return 0;

}

unsigned long fill_value = 0;

unsigned long only_pattern = pattern;

if (width < sizeof(long)) {

only_pattern &= ~(-1L << width);

}

for (int i = 0; i < sizeof(long) * 8 / width; i++) {

fill_value = (fill_value << width) | only_pattern;

}

return fill_value;

}