Written by Nick Troccoli and Lisa Yan, based on walkthroughs by Ryan Noon, Nate Hardison and John Louie

Lecture Review

Here are key concepts relevant to this week's lab:

-

condition codes are special flags that are automatically updated by the result of the most recent arithmetic or logical operation.

-

instructions like conditional jumps, conditional moves, and

setcan behave based on the state represented by the condition codes. -

The special

%ripregister stores the address of the next instruction to execute. If we jump to another instruction,%ripis updated. -

ifstatements are usually implemented by testing the inverse of the if statement check, and jumping past the if statement body if the test succeeds. -

whileloops are usually implemented by jumping to the test, and then jumping back to the body if the condition holds. -

for loops are built on top of while loops, using the same format but adding an initialization and update step.

-

The special

%ripregister stores the address of the next instruction to execute. If we jump to another instruction or call another function,%ripis updated. In particular, when we call another function, we must save the caller's next instruction to execute so that we can resume there when the callee finishes. Thecallinstruction does this for us automatically by storing it on the stack, and theretinstruction pops the value off into%rip. -

The special

%rspregister stores the address of the current top of the stack. Instructions adjust%rspeither be explicitly incrementing or decrementing it to make more or less space, or by pushing or popping things on/off the stack using thepushandpopinstructions. -

If we call a function, we must put parameters we want to pass into the correct special registers to store the 1st - 6th parameters. Parameters after the 6th (if any) are pushed onto the stack.

-

If we call a function, when the function finishes we can find its return value (if any) in the special

%raxregister. -

Local variables may sometimes be stored in registers rather than on the stack for optimization purposes, but there are several reasons why a local variable must be on the stack:

- if we have run out of registers

- if the program uses the

&operator on a local variable, we must put it on the stack so that it has an address (registers do not have addresses) - if we have array or struct data, and we need to use address arithmetic (e.g. can't index into a register)

-

Some registers are labeled as callee-owned or caller-owned (see the reference sheet for the full list!).

- Callee-owned means that a function can feel free to use that register without worrying about what was previously put there by its caller. However, if it calls a function itself, it should probably save the register's contents somewhere else first, as its callee may use that register as well!

- Caller-owned means that a function must save and put back later the existing value of the register if it wants to use it. However, if it calls a function itself, it does not need to worry about that register's contents being overwritten, as this distinction guarantees that a callee will ensure the register is ultimately the same as before it was called.

Solutions

1) GDB and Stack Mechanics

Q1: What is the significance of this 8 byte value at the top of the stack right when kermit is called? (Hint: what does the call instruction put there?). Try disassemble main to see if this value pops up anywhere.

A1: This is the return address - the address of the caller instruction that the program should resume at when this function is done. Here, it should be the address of the instruction in main immediately following the call kermit instruction.

Q2: Why must kermit push these registers onto the stack before it uses them? (Hint: are they caller owned? Or callee-owned?)

A2: %rbp and %rbx are caller-owned registers, so the caller assumes they will look the same before and after we execute. Therefore, if we wish to use them, it is our responsibility to preserve the existing value and put it back later when we are done.

Q3: To where does kermit copy binky's return value to use it later? Step through to confirm your understanding.

A3: kermit saves the return value from binky into %ebx - the other of the caller-owned registers it uses.

Q4: What pointer type should we cast $rdi to in order to complete this expression? (Hint: what pointer type is arr really?) Try out your idea to see if it prints the array!

A4: It should be an int *, since it is a pointer to the first element of the array. Thus, the expression in GDB should be print ((int *)$rdi)[0]@$rsi.

Q5: How does this instruction that is modifying arr[1] connect back to the C code?

A5: The instruction is mov %edx,(%rcx). This is moving the incremented value (in %edx) into the memory location for the ith array element.

2) Stack Misuses

This problem is a crucial introduction to examining stack behavior and vulnerabilities. It is very useful (hint hint) for part of assign5! Our goal is to help you feel more comfortable drawing stack diagrams and using them to understand program behavior.

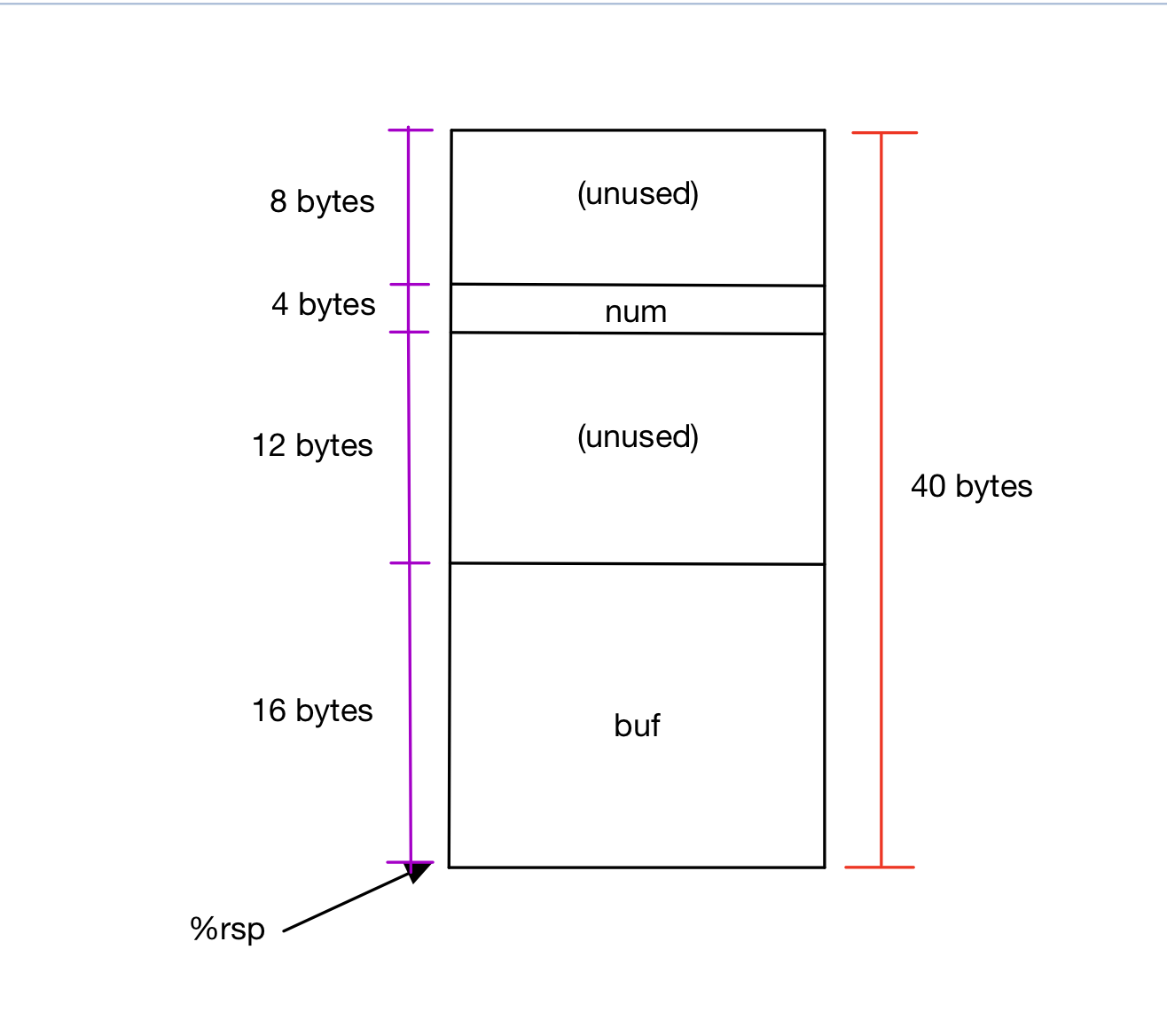

The core idea for this problem is that gets will write past the end of buf if the user enters a sufficiently long input. It turns out that num lives above buf on the stack, so if we write far enough we will overwrite num. Then, when the function returns it, it will return the value we wrote instead of 2.

Part 1: Stack Diagram

Here is the annotated assembly for the start of greet:

sub $0x28,%rsp # 40 bytes

movl $0x2,0x1c(%rsp) # num = 2

mov $0x402008,%rdi # printf string

mov $0x0,%eax # printf 0 param

callq 0x401050 <printf@plt>

mov %rsp,%rax # buf start

mov %rax,%rdi # buf start

callq 0x401060 <gets@plt>

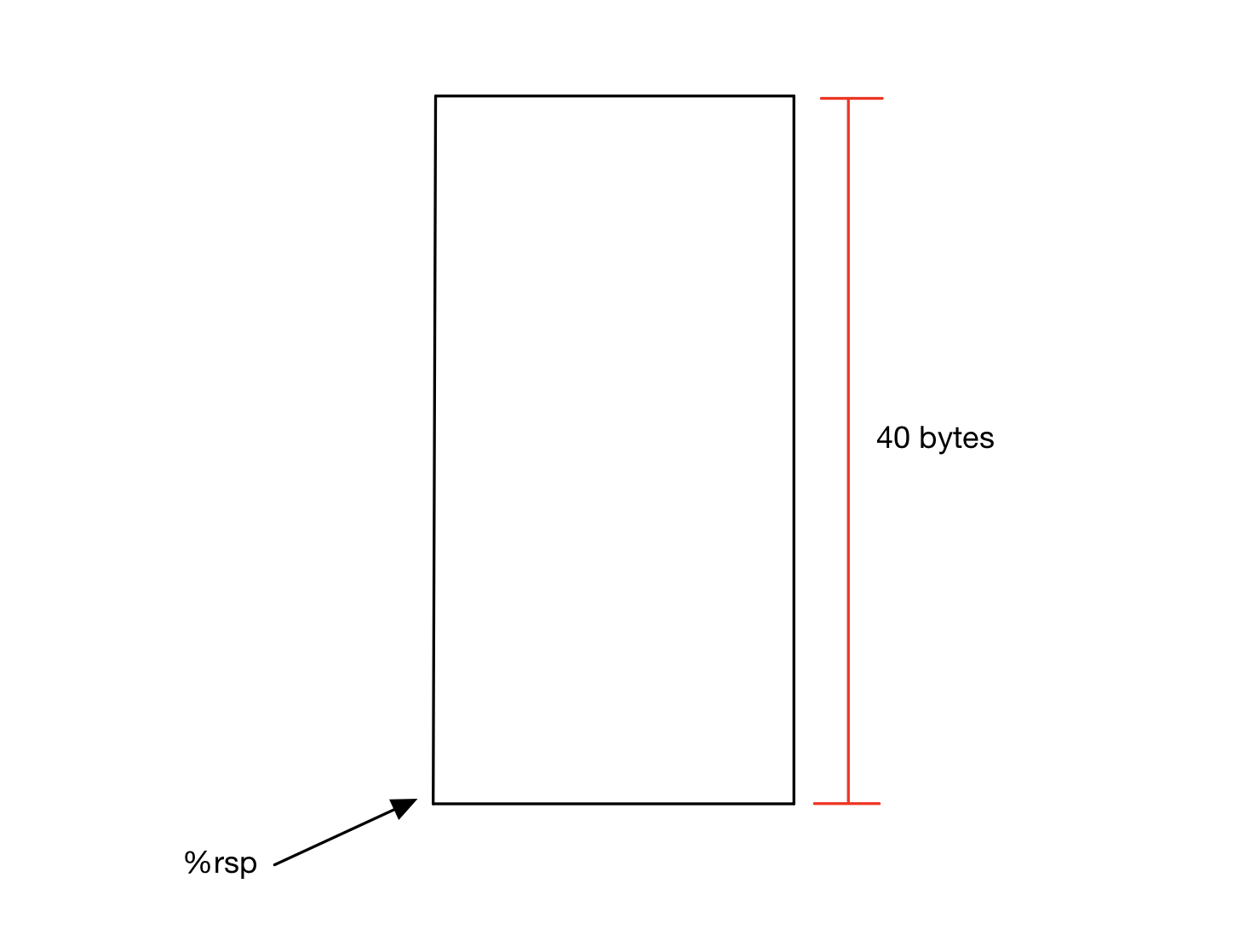

Q1: In the first instruction, how much stack space is initially reserved for greet? This is the initial size of our stack frame. %rsp points to the "top" of the stack (likely the bottom in your diagram).

A1: 40 bytes.

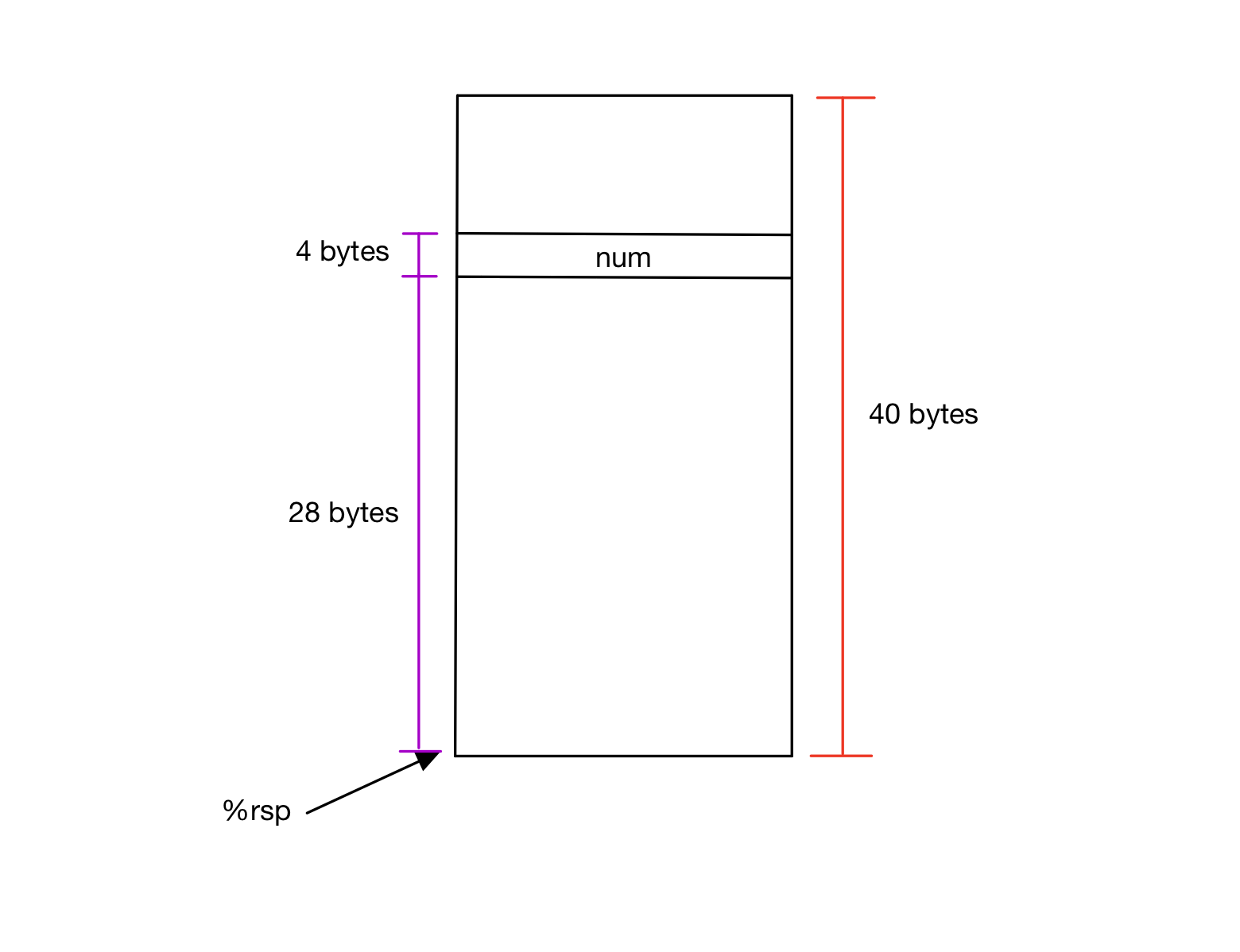

Q2: In the second instruction, we copy 2, presumably into num. Where is num stored, relative to %rsp? Add that to your diagram.

A2: it is at $rsp + 0x1c, or $rsp + 28.

Q3: In the last 3 instructions, we set up the call to gets. In the C code, we pass in buf (a 16-byte buffer) as the parameter to gets. Looking at the assembly, what does that tell us about where buf is stored relative to %rsp? Add that to your diagram.

A3: it is at $rsp.

Part 2: Stack Smash

Q4: What is the shortest input (remember the null terminator!) that we can specify that will overwrite part of num? What is it overwritten to?

A4: If we enter 28 characters, the null terminator (29th character) will overwrite the first byte of num and make num 0.

Q5: The ASCII character with numeric value 107 is k. How can we craft an input that overwrites the first byte of num with the letter k, and the second byte with the null terminator?

A5: If we enter 29 characters, and the last one is k, we will overwrite the first byte of num with k, and the second byte of num with a null terminator. Thus, num will become 107!

Checkoff Answers

- Kermit. What is the significance of the 8 byte value at the top of the stack right when

kermit(or any other function) is called? This is the return address - the address of the caller instruction that the program should resume at when this function is done. Here, it should be the address of the instruction inmainimmediately following thecall kermitinstruction. - Printing in GDB. Assume we are working with another program and we know that

%rbxrepresents an array of strings (in other words, it is a pointer to the first element, which is achar *). What GDB expression could we print to see the element at index 2 in this array?print ((char **)$rbx)[2]orprint *((char **)$rbx + 2). - Watchpoints. In the

clydefunction, what assembly instruction is responsible for modifyingarr[1]? The instruction ismov %edx,(%rcx). This is moving the incremented value (in%edx) into the memory location for the ith array element. - Stack Diagrams. In the

greetfunction, how much space is there on the stack between the end ofbufand the start ofnum?12 bytes. - Doing the impossible. How is it possible that

greetcan return 107?bufis a fixed size, but the user could enter a string of any length. Therefore, the string could be written beyond the bounds ofbufand into memory next to it on the stack.numis stored 12 bytes afterbufon the stack, so if we write a sufficiently long string, it will overwrite the memory fornum. Specifically, if we enter 29 characters, and the last one isk, we will overwrite the first byte ofnumwithk, and the second byte of num with a null terminator. Thus,numwill become 107!

Additional Thought Questions

- Why are the registers used for function parameters completely fixed, yet no conventions apply to where locals are stored? Even though a local variable can be stored at any address on the stack, we can specify its location via its address. However, without assigned registers for parameters, we would not be able to tell another function which register stores its parameters since registers do not have addresses.

- Explain the rules for caller-owned versus callee-owned register use. What is the advantage of this arrangement relative to a simpler scheme such treating all registers as caller-owned or callee-owned? Caller owned registers must be restored by the callee before returning. This means callees must preserve their existing values, but callers may assume that their values will be preserved across function calls. Callee owned registers do not have to be restored by the callee before returning. This means callees do not have to preserve their existing values, but callers cannot assume that their values will be preserved across function calls. Having both provides flexibility to use what's most appropriate in each situation (e.g. if all were callee-owned, we'd have to store values on the stack to preserve them; if all were caller-owned, we'd always have to save existing register values, even if that function isn't calling any other functions)

- Explain how you might go about sketching a stack diagram for a function given its assembly. Look at assembly instructions that modify the stack pointer (e.g.

push,pop,sub, etc.) and track changes over time. Match up the assembly to the C code to see where different variables live.

[Optional] Extra Problems

1) Recursion

Q1: How is an invalid number causing a memory problem? Run factorial under gdb on argument -1. Use backtrace to find out where the program was executing at the time of the crash. Does this shed some light on what has gone wrong?

A1: The program should crash with -1 because of a stack overflow - there were too many stack frames, and so the program ran out of stack memory. This is because the parameter is an unsigned int, so a negative number is cast to a positive one, and bypasses the initial check!

- Get into

gdband figure out how big eachfactorialstack frame is. Here are two different strategies; try both! Both approaches should give a stack frame size of 16 bytes. There is onepushand onecallinstruction, for example. And the difference between two frame addresses should be 16 bytes (0x10).

Q2: In the OS on myth, the stack segment is configured at program start to a particular fixed limit and cannot grow beyond that. The bash shell built-in ulimit -a (or limit for csh shells) displays various process limits. What does it report is the process limit for stack size?

A2: 8192KB

Q3: How close is that depth to the maximum you estimated?

A3: The math should say 8192KB / 16B = 8192 * 1024 / 16 = 524,288 frames. This is pretty close to the topmost stack number, 524190!

Q4: Woah! What happened? Did the compiler "fix" the infinite recursion? Disassemble the optimized factorial to see what the compiler did with the code.

A4: It's subtle, but the recursion was replaced by a loop! It removes any need for stack space at all (no more push or call) so the function can run as long as needed to compute an answer - in this case, for a negative number it will be cast to a large positive number and continue executing - it overflows from the multiplication and thus eventually evaluates to 0.

2) "Channeling" Information Between Functions

This problem shows an example of the consequences of stack memory not actually being cleared out when it is no longer used - instead, the stack "pops" elements off simply by adjusting %rsp. This means previous memory is still there until it's overwritten in the future by another function's stack frame that is put on top of it!

Q1: Review the code in channel.c. The init_array and sum_array function each declare a stack array. The init function sets the array values, the sum function adds the array values. Neither init nor sum takes any arguments. There is a warning from the compiler about sum_array, what is it?

A1:

channel.c: In function ‘sum_array’:

channel.c:38:20: warning: ‘nums[i]’ may be used uninitialized in this function

sum += nums[i];

^

Q2: The program calls init_array() then sum_array(). Despite no explicit pass/return between the two calls, the array seems to be magically passed as intended. How are these functions communicating? The term for this is "channeling". (Hint: when data is popped off the stack, it isn't cleared out - it just increments %rsp to indicate that memory area can be reused).

A2: sum_array is able to read the contents of the stack frame that init_array left behind because sum_array is called immediately afterwards by the same caller, so both functions' stack frames are put at the same place in memory. Additionally, they have the exact same local variable nums, that overlays right on top of nums from init_array, so even though sum_array doesn't have any parameters, it "sees" the array that init_array just left behind and is able to read it as though it were a parameter.

Q3: The program's second attempt to channel the array from init to sum fails. What is different about this case?

A3: printf is called in between init_array and sum_array. This means that printf uses that stack space before sum_array, and so it may overwrite or change the memory contents there to no longer be what init_array left behind.

3) Clobbering Memory

Q1: When i changes from 2 to 3, execute disassemble in GDB to see exactly what assembly instruction is responsible for changing i at that point. As a tip, the => will point to the instruction that is about to be executed, so the one that changed i comes before this. Where does this instruction come from in the C code?

A1: The instruction is addq $0x1,0x28(%rsp), which comes from the i++ in the code.

Q2: When i changes from 5 to 0, execute disassemble again in GDB to see exactly what assembly instruction is responsible for changing i at that point. It looks like it's a different instruction from the one changing i before. What is that instruction? Where does it come from in the C code? What code is thus responsible for clobbering i?

A2: The instruction is movq $0x0,(%rsp,%rax,8), which comes from the arr[i] = 0 in the code. Thus, the code responsible for clobbering i is the assignment to arr[i] = 0, since i gives an address too far when we do the pointer arithmetic and then we assign zero to the value of i and start the loop all over again as a result!