Assignment 1: Game of Life

Created/Updated by Julie Zelenski, Jerry Cain, Keith Schwarz, Cynthia Lee, Marty Stepp, and Nick Troccoli.

Due: Friday, October 5, 11AM

Must be done individually

A still image of the Game of Life

For your first assignment... We make the Game of Life!

The purpose of this assignment is to gain familiarity with basic C++ features such as functions, strings, and I/O streams, using provided libraries, and decomposing a large problem into smaller functions. This is an individual assignment. You should write your own solution and not work in a pair on this program.

The Game of Life is a simulation originally conceived by the British mathematician J. H. Conway in 1970 and popularized by Martin Gardner in his Scientific American column. The game models the life cycle of bacteria using a two-dimensional grid of cells. Given an initial pattern, the game simulates the birth and death of future generations of cells using a set of simple rules. In this assignment you will implement a simplified version of Conway's simulation and a basic user interface for watching the bacteria grow over time.

The starter code for this project is available as a ZIP archive:

To run the demo, unzip the Demo folder and right click on the contained JAR file to run it. Your program should exactly match the demo output content (disregard text colors). Note that the demo does not include the Life GUI - it only includes the console portion of the assignment.

Helpful Assignment Resources

- Style Guide

- Diff Tool

- Stanford Library Docs

- CppRef (C++ reference)

- C++.com (C++ reference)

- C++ Handout

- Debugging Handout

Overview

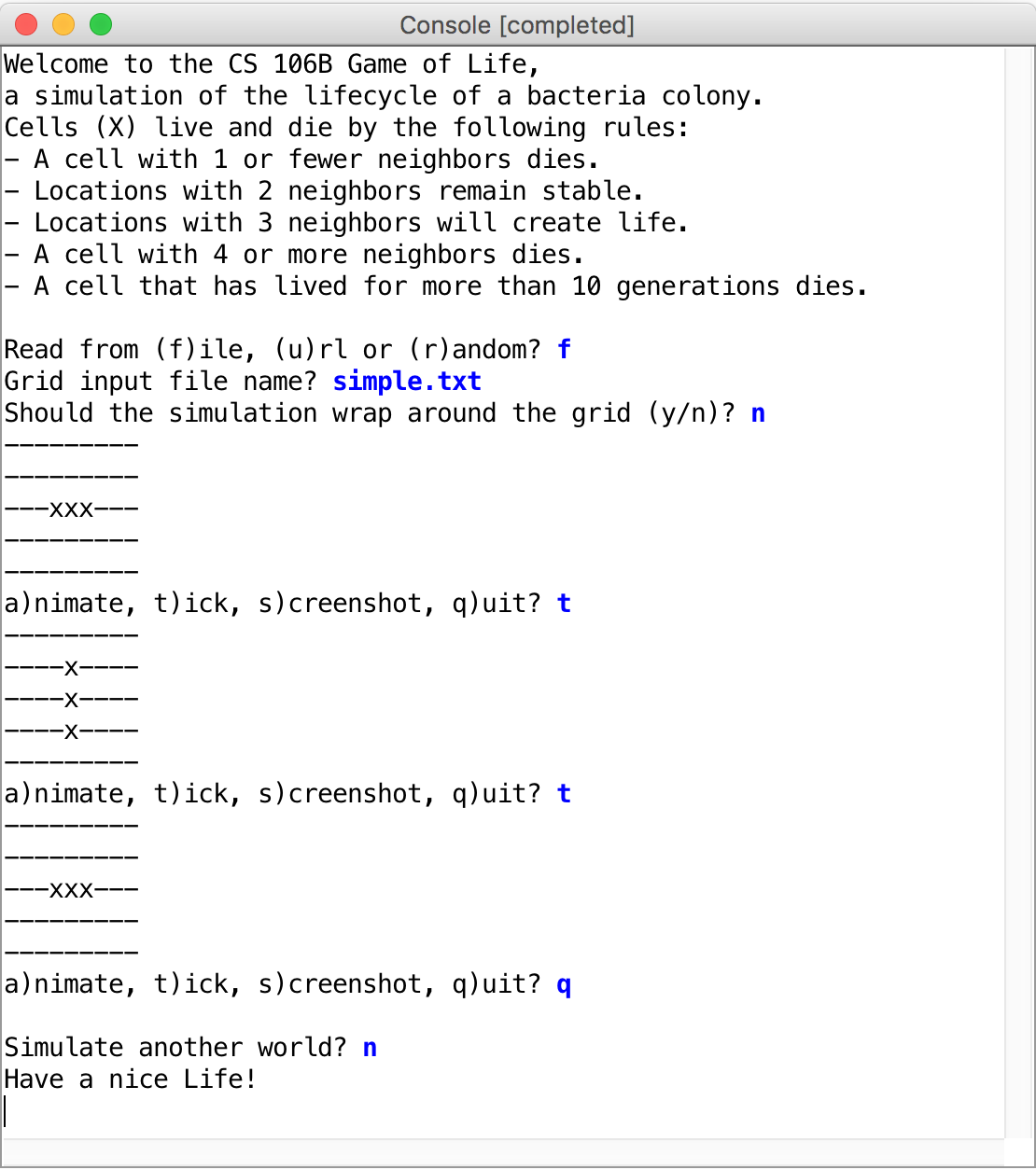

Your Game of Life program should begin by prompting the user for a filename, url, or random grid option and use that to set the initial state of your bacterial colony grid. Then, it should ask if the simulation should wrap around the grid (see below for the details of wrapping). Then the program will allow the user to advance the colony through generations of growth. The user can type t to "tick" forward the bacteria simulation by one generation, or a to begin an animation loop that ticks forward the simulation by several generations, once every 50 milliseconds; or q to quit. They can choose to take a screenshot as well with s. Your menu should be case-insensitive; for example, an uppercase or lowercase A, T, or Q should work. Once the user finishes a simulation, the program should ask them whether they would like to run another simulation.

Simple Example:

Here is an example log of the interaction between your program and the user (with console input in blue).

Many Examples:

Of course there are many other interactions you could have. Here is a bunch more examples. They show what to do in many cases, for example bad input filenames or URLs.

Example Diff Tool

Files

You will turn in only the following files:

life.cpp, the C++ code for the Game of Life simulationdebugging.txt, a file detailing a bug you encountered in this assignment and how you approached debugging it

The ZIP archive contains other files and libraries; you should not modify these. When grading/testing your code, we will run your life.cpp with our own original versions of the support files, so your code must work with them.

Game of Life Simulation Rules

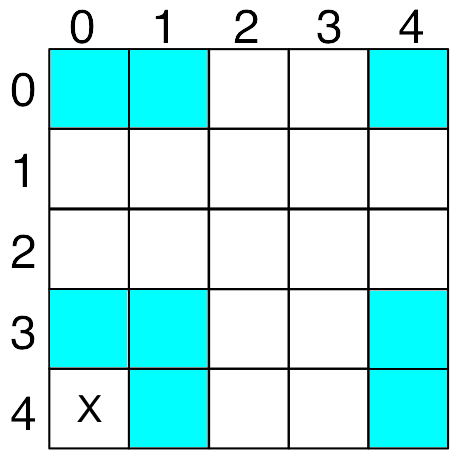

Each grid location is either empty or occupied by a single living cell (X). A location's neighbors are any cells in the surrounding eight adjacent locations. In the example at right, the shaded middle location has three neighbors containing living cells. A square that is on the border of the grid has fewer than eight neighbors in the non-wrapping version of the simulation (see below for the wrapping version). For example, the top-right X square in the example at right has only three neighboring squares, and only one of them contains a living cell (the shaded square), so it has one living neighbor.

The simulation starts with an initial pattern of cells on the grid and computes successive generations of cells according to the following rules:

- A location that has zero or one neighbors will be empty in the next generation. If a cell was there, it dies.

- A location with two neighbors is stable. If it had a cell, it still contains a cell. If it was empty, it's still empty.

- A location with three neighbors will contain a cell in the next generation. If it was unoccupied before, a new cell is born. If it currently contains a cell, the cell remains.

- A location with four or more neighbors will be empty in the next generation. If there was a cell in that location, it dies of overcrowding.

- A cell that ages more than 10 generations dies, and will be empty the next generation, regardless of how many neighbors it has.

The births and deaths that transform one generation to the next all take effect simultaneously. When you are computing a new generation, new births/deaths in that generation don't impact other cells in that generation. Any changes (births or deaths) in a given generation k start to have effect on other neighboring cells in generation k+1.

Check your understanding of the game rules by looking at the following example. The first generation, at the left, turns into the second generation, at the right, following the above rules (assuming each cell is young):

Here is a second example. The pattern at right does not change on each iteration, and will eventually die, because each cell has exactly three living neighbors. This is called a "stable" pattern or a "still life".

Input Grid Data Files:

The grid of bacteria in your program gets its initial state from one of a set of provided input text files, which follow a particular format. When your program reads the grid file, you should re-prompt the user if the file specified does not exist. If it does exist, you may assume that all of its contents are valid. You do not need to write any code to handle a misformatted file. The behavior of your program in such a case is not defined in this spec; it can crash, it can terminate, etc. You may also assume that the input file name typed by the user does not contain any spaces.

You must also support allowing the user to enter a URL instead of a filename to download a life text file. When your program reads the URL, you should also re-prompt the user if the URL specified does not exist. If it does exist, you may assume that all of its contents are valid. You may also assume that the input URL typed by the user does not contain any spaces.

NOTE: we have put the same colony .txt files that come with the starter code on the course website, for you to test loading from a URL. For example, to load glider.txt from a URL, input the URL http://cs106x.stanford.edu/resources/life/files/glider.txt, or modify this URL for any other colony file you would like to test via URL.

You should finally support the ability to generate random grids. If the user selects this option, you should prompt them for a number of rows and columns, and then generate a random grid with a 50% chance of each cell being empty, and 50% chance of a cell having life in it with age 1. Take a look at the Stanford Libraries for random number functions, which may come in handy.

In each input file, the first two lines will contain integers r and c representing the number of rows and columns in the grid, respectively. The next lines of the file will contain the grid itself, a set of characters of size r x c with a line break (\n) after each row. Each grid character will be either a '-' (minus sign) for an empty dead cell, or an 'X' (uppercase X) for a living cell of age 1. The input file might contain additional lines of information after the grid lines, such as comments by its author or even junk/garbage data; any such content should be ignored by your program.

The input files will exist in the same working directory as your program. For example, the following text might be the contents of a file simple.txt, a 5x9 grid with 3 initially live cells (the arrow notes are not part of the actual file):

5 ← number of rows tall 9 ← number of columns wide --------- --------- ← - is a dead cell ---XXX--- ← X is a living cell --------- ---------

Implementation Details

Grid: The grid of bacterial cells could be stored in a 2-dimensional array, but arrays in C++ lack some features and are generally difficult to use. They do not know their own length, they cause strange bugs if you try to index out of the bounds of the array, and they require understanding C++ topics such as pointers and memory allocation. So instead of using an array to represent your grid, you should use an object of the Grid class, which is part of the provided Stanford C++ library and comes with several handy methods and features (see the course lecture slides and/or section 5.1 of the textbook as well).

In particular, you can use the = assignment operator to copy the state of one Grid object to another. Since you don't know the size of the grid until you read the input file, you can call resize on the Grid object once you know the proper size.

Checking for valid input: Your program needs to check for valid user input in a few places:

- When the user selects how they wish to load in a grid and they type anything other than the three predefined commands of

f,uorr(case insensitively) you should re-prompt the user to enter a new command. - When the user types the grid input file name or URL, you must ensure that the file or URL exists, and if not, you must re-prompt the user to enter a new one.

- If the user is prompted to enter an action such as

tfor tick orafor animate, if the user types anything other than the predefined commands ofa,t,s,q(case-insensitively), you should re-prompt the user to enter a new command. - If the user is prompted to enter an integer such as the number of frames of animation for the animate command, or the size of their random grid, your code should re-prompt the user if they type a non-integer token of input. (If they do type an integer, you may assume that it is a valid value greater than 0; you don't need to explicitly test or check its value.)

- If the user is prompted to enter whether or not they want wrapping, or whether they would like to run the program again, and types anything other than something starting with

yorn(case insensitive), you should re-prompt the user to enter a new answer.

getInteger and getYesOrNo. These functions come from Stanford library files "filelib.h" (documentation) and "simpio.h" (documentation).

Animation: When the user selects the animation option, the console output should look like the following:

a)nimate, t)ick, s)creenshot, q)uit? a How many frames? xyz Illegal integer format. Try again. How many frames? 5 (five new generations are shown, with screen clear and 50ms pause before each)

The screen is supposed to clear between each generation of cells, leading to what looks like a smooth animation effect. See the demo JAR for what this looks like.

To help you perform animation, use the following global functions from the Stanford C++ library:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

pause(ms);

|

Causes the program to halt execution for the given number of milliseconds |

clearConsole();

|

Erases all currently visible text from the output console (call this between frames) |

I/O:

Your program has a console-based user interface. You should pop up the Stanford graphical console by including "console.h" (documentation) in your program. Produce console output using cout and read console input using simpio (documentation). You should not use cin.

When printing out a colony to the console as text, dead cells should be printed as '-'. Living cells should be printed with a lowercase 'x' if they are ages 1-4, and an uppercase 'X' if they are older than 4.

You will also write code for reading input files. See ifstream (documentation) and iurlstream (documentation) examples from the lecture slides. Make sure to close your input file streams when done reading. Also note that, for saving screenshots, you do not need to get a valid filename (that already exists) before saving the screenshot - the filename may exist, or may not.

A non-trivial part of the program involves string manipulation. You may want to look up members of the C++ string class (documentation) such as find, length, substr, and so on and the Stanford Library strlib functions (documentation).

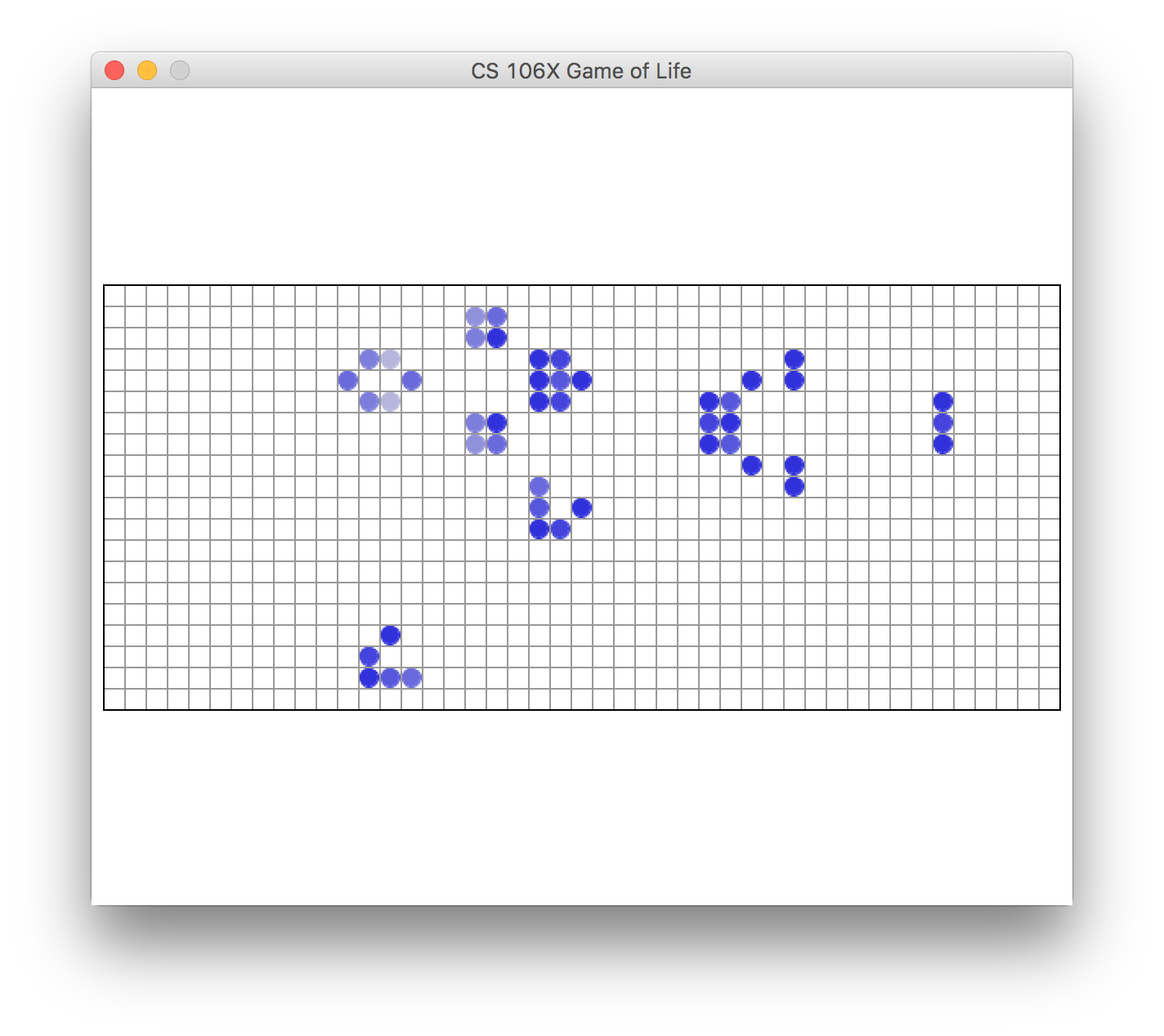

Graphical Display

As a required part of this assignment, you must also add code to use an instructor-provided graphical user interface (GUI) with your program. The GUI does not replace the console UI; it can't be clicked on to play the game, for example. It just shows a display of the current game state. The GUI should first appear once the user has loaded a valid file and selected their wrapping preference, and it should draw the colony state for each generation. To use the GUI, call the functions below:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

LifeGUI::clear();

|

Erases any filled circles for cells in the grid. |

LifeGUI::fillCell(row, col, age);

|

Draws a circle for the cell at the specific row and column, with the given age. The cell will not immediately appear on the screen; the client must also call repaint to see any newly drawn cells. The idea is that on each generation of your simulation, you should call fillCell on all living cell locations, and then call repaint once to see all of the changes. If the location given is not in bounds, or if the age is higher than 10, an error is thrown.

|

LifeGUI::initialize();

|

Sets up the state of the GUI and pops up the GUI window on the screen. This needs to be called only once by the client. |

LifeGUI::repaint();

|

Redraws the GUI window, showing any newly drawn cells that have been drawn using fillCell since the window was last repainted.

|

LifeGUI::resize(rows, cols);

|

Informs the GUI about the given number of total rows and columns in the simulation. Calling this will erase the graphics window completely, draw a black border around the simulation rectangle which is centered in the window, and draw light gray grid lines around each cell. This function can be used at the beginning of a simulation or between generations to clear the window before drawing the next generation. |

LifeGUI::screenshot(filename);

|

Saves the current GUI to an image file (filename should end in .png). If this file does not exist, it is created. |

These are static methods. What this means is that, to call them, you must write exactly the syntax above, including the LifeGUI:: preceding the function name. For instance, if I wanted to put a cell with age 2 at location (3, 4) I would write LifeGUI::fillCell(3, 4, 2);.

Wrapping:

The non-wrapping version of the assignment treats the edges of the grid as the end of the game world. Cells on the border do not always have eight neighbors. In the wrapping version, all cells will have eight neighbors, as follows: the right-most squares are considered to be "neighbors" of the left-most, and the top-most are considered to be "neighbors" of the bottom-most. In order to provide wrapping functionality, modify your game logic so that these rules are followed. This will allow moving patterns such as "gliders" to wrap around indefinitely.

The logic for this is not too difficult, and you may want to

use the remainder operator (%) to perform part of

this task. The remainder function works as follows:

(a % b) returns the remainder of a / b

For positive values, the operator returns the value of the remainder,

which "wraps" around to the value. E.g., 6 % 5 is

1, which would

be correctly wrapped on a grid from 0-4 (which has 5 values).

For negative values, the remainder function does not wrap in C++, but wrapping can be accomplished by simply adding the number of rows or columns in the grid to the negative value. In fact, to wrap properly in all cases, simply add the number of rows or columns to the location, and then apply the remainder operator.

For example, let's say you were checking the bottom left corner of a 5x5 grid (with indexes 0-4 for both the rows and columns), at location (4,0), as shown in the diagram below.

The blue squares show the neighbors with wrapping, and going clockwise from the top-left corner of the neigbors, would be at locations (3,-1), (3,0), (3,1), (4,-1), (4,1), (5,-1), (5,0), and (5,1). But, both the negative values and the values above 4 are out of bounds. If we apply the remainder operator as detailed above, we will get a proper wrapping of the values. If we add the corresponding number of rows or columns (5 in this case, for both), and then apply the remainder operator with the same value to each of the coordinate pairs, we will get a proper wrap. Using coordinate (5, -1) as an example, this would become:

((5 + 5) % 5, (-1 + 5) % 5) = (10 % 5, 4 % 5) = (0, 4)

and that coordinate is properly wrapped to the top right corner.

Many of the provided colonies will behave differently with and without wrapping. For instance, without wrapping, the glider colony will move to the bottom of the screen in a straight line and stop. With wrapping, the glider colony will move to the bottom of the screen and continue wrapping around and moving forever in a straight line.

Debugging Aspect, debugging.txt

Along with your code, you should also submit debugging.txt. In this file, you should write 1-2 paragraphs describing a bug you encountered and how you debugged it. If you got help in LaIR or office hours, explain how the help unblocked you. Please read the debugging handout for ideas on the sorts of questions you should be answering.

Development Strategy and Hints:

Development strategy: It is tempting to try to write your entire program and then try to compile and run it; we do not recommend that strategy. Instead, you should develop your program incrementally: Write a small piece of functionality, then test/debug it until it works, then move on to another small piece. This way you are always making small consistent improvements to a base of working code. Here is a possible list of steps to develop a solution:

- Intro: Get your basic project running, and write code to print the introductory welcome message.

- File input: Write code to prompt for a filename, and open and print that file's lines to the console. Once this works, try reading the individual grid cells and turning them into a

Gridobject. Print theGrid's state on the console usingtoStringjust to see if it has the right data in it. Use a simple test case, e.g.simple.txt. - Grid display: Write code to print the current state of the grid, without modifying that state.

- Updating to next generation: Write code to advance the grid from one generation to the next.This is one of the hardest parts of the assignment, so you will probably need lots of testing and debugging before it works perfectly. Insert cout statements to print important values as you go through your loops and code. Try printing out what indexes your code is examining, along with your count of how many neighbors each cell has, to make sure you are counting them properly.

- Overall menu and animation: Implement the program's main menu and the animation feature. If all of the preceding steps are finished and work properly, this should not be as difficult to get working.

- Complete the rest of the features: including the GUI

Updating from one generation to the next: When you are trying to advance the bacteria from one generation to the next, you cannot do this "in place" by modifying your grid as you loop over it. Doing so will change the cells and their neighbors and break the neighbor counts for nearby cells. Think about how you can solve this.

Output: We want your output to match ours exactly. This includes identical spacing, such as the extra spaces after the phrase, "Grid input file name? " Some students get deductions for minor output formatting errors. Please run the web Output Comparison Tool on several test cases to make sure it matches without any differences.

Hints: Here are some other miscellaneous tips that may help you:

- A common bug when counting neighbors of a given cell is to count that cell itself. Don't do that.

- Reading a grid file line by line may be easier than reading it character by character.

- If your editor is unable to compile your program, complaining about "cannot open output file ...: Permission denied", you need to close/terminate all windows from previous runs of the program.

- You can declare a constant in your program at the top of your file by declaring the variable with the

constkeyword before the type. E.g.const int CONSTANT_VAL = 0;. You should name constants using all-caps to indicate they will not change. Constants can then be referenced anywhere in your program. See the style guide for more about using constants in your program.

Style Guidelines

To achieve a high style score, submit a program with high code quality that conforms to the guidelines presented in our course (see the Assignments dropdown). There are many general C++ coding styles that you should follow, such as naming, indentation, commenting, avoiding redundancy, etc. While there are many valid programming styles in various contexts, the most important overall stylistic trait a programmer can have is the ability to be given a set of style guidelines and follow them rigorously and consistently. In general, limit yourself to the material that was taught in class so far.

Before getting started, you should read our Style Guide for information about expected coding style. You are expected to follow the Style Guide on all homework code. The following are some points of emphasis and style constraints specific to this problem:

C++ idioms: For full credit, you must use C++ facilities (cout, ifstream, string) instead of C equivalents (printf, fopen, char*).

Procedural decomposition: Your main function should represent a concise summary of the overall program. It is okay for main to contain some code, such as calls to other functions or brief console output statements to cout. But main should not perform too large a share of the overall work itself directly, such as reading the lines of the input file or performing the calculations to update the grid from one generation to the next. Instead, it should make calls to other functions to help it achieve the overall goal. You should declare function prototypes (each function's header followed by a semicolon) near the top of your file for all functions besides main.

Each function should perform a single clear and coherent task. No one function should do too large a share of the overall work. As a rough estimate, a function whose body (excluding the header and closing brace) has more than 30 lines is likely too large. You should avoid "chaining" long sequences of function calls together without coming back to main, as described in lecture. Your functions should also be used to help you avoid redundant code. If you are performing identical or very similar commands repeatedly, factor out the common code and logic into a helper function, or otherwise remove the redundancy.

Parameters, Returns, Values, References: Since your program will have several functions and those functions will want to share information, you will need to appropriately pass parameters and/or return values between the functions. Each function's parameters and return values should be well chosen. Do not declare unnecessary parameters that are not needed by your function. A particular point of emphasis on this assignment is that you should demonstrate that you understand when it is proper to pass by reference, and when it is proper for a parameter to be declared const. You should also demonstrate that you understand when it is better to return a result and when it is better to store a result into an 'output' reference parameter.

Variables and types: Use descriptive variable and function names. Use appropriate data types for each variable and parameter; for example, do not use a double if the variable is intended to hold an integer, and do not use an int if the variable is storing a true/false state that would be better suited to a bool. When manipulating strings, favor talking to string objects over individual char values when possible, and use the string object's built-in methods as opposed to rewriting similar behavior yourself. Do not declare any global variables or static variables; every variable in your program must be declared inside one of your functions and must exist in only that scope. No single variable's scope should extend beyond a single invocation of a single function.

Commenting: Your code should have adequate commenting. The top of your file should have a descriptive comment header with your name, a description of the assignment, and a citation of all sources you used to help you write your program. Each function should have a comment header describing that function's behavior, any parameters it accepts and any values it returns, and any assumptions the function makes about how it will be used. For larger functions, you should also place a brief inline comment on any complex sections of code to explain what the code is doing. See the programs written in lecture or the Course Style Guide for examples of proper commenting.

Possible Extra Features:

Thats all! You are done. Consider adding extra features.