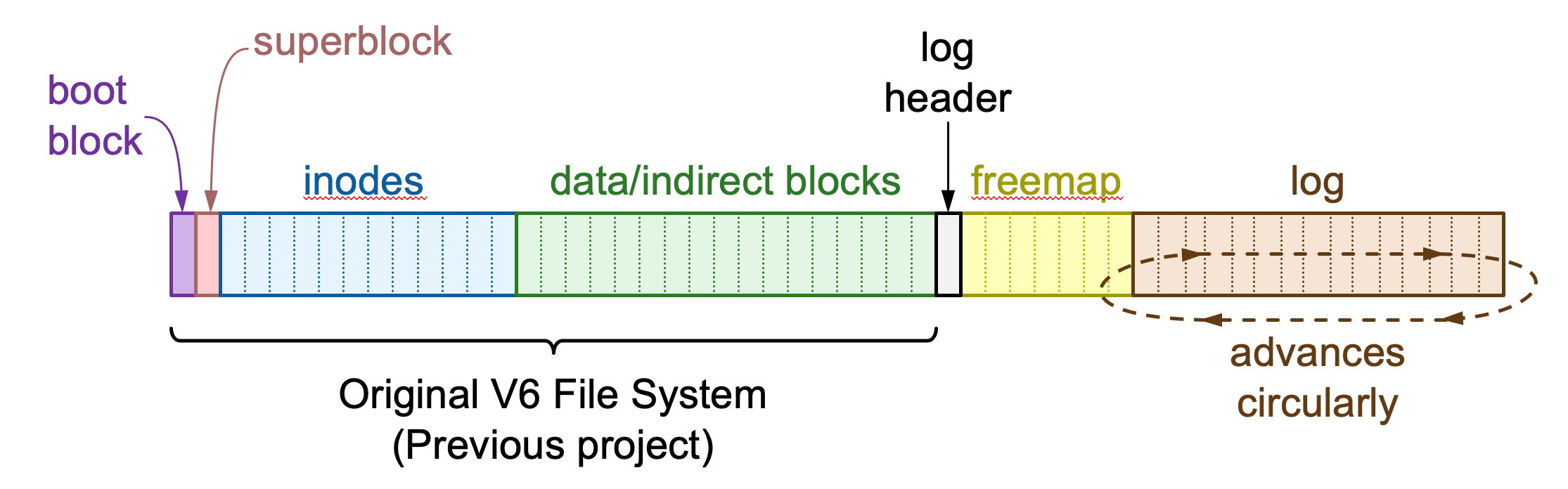

For this assignment, we took the existing design of the Unix V6 filesystem and retrofitted a freemap and log on top of it. The on-disk layout of this new "journaling V6 file system" consists of the following sections:

- The boot block (1 sector)

- The superblock (1 sector)

- Inodes (variable-length)

- Data blocks (variable-length)

- The log header (1 sector)

- The free-block bitmap or freemap (variable-length)

- The log (variable-length)

Diagram by John Ousterhout

Diagram by John Ousterhout

Sections 1-4 are identical or nearly identical to the original V6 file system layout, which you used in the previous project. Their layout is defined by data structures and constants in the header file layout.hh.

Sections 5-7 were added for this project. Their layout is defined by the logentry.hh header file. Since nobody runs the V6 file system on raw hard disks any more---V6 file system images exist only as files on other file systems---we simply extend the file containing a V6 file system image to accommodate the new areas required by journaling.

Filesystem Sections

Boot Block

This block is essentially unused, but the first two bytes must be 4 and 7 or mountv6 will not recognize the disk image.

Superblock

The superblock is essentially the same as in 1975, except that we've coopted two of the unused bytes to add two more fields:

struct filsys {

...

uint8_t s_uselog; // Use log

uint8_t s_dirty; // File system was not cleanly shut down

...

};

The s_uselog byte, when non-zero, indicates that our new

21st-century logging functionality has been enabled for this particular file system volume.

The s_dirty field is set to 1 whenever the file system is opened, and set to 0 when it is closed cleanly. If your file system crashes, s_dirty will be 1, and mountv6 will refuse to mount it again until you have repaired the damage unless you use the --force flag (if you want to see how bad a corrupt file system can be in action).

There's one more change to the superblock. Originally, V6 stored free blocks in a linked list 100-wide. The superblock stored s_nfree free blocks (0--100) in an array s_free, with s_free[0] (if non-zero) pointing to a disk block containing 100 pointers to other free blocks and so on. This format is not convenient for journaling,

so we set s_nfree to zero and instead dedicate a portion of the disk to a bitmap, containing one bit per data block, where 1 indicates the block is free and 0 indicates it is allocated. For brevity, we refer to the "free-block bitmap" as the freemap and store it in a structure field called freemap_.

V6 also stores a vector of up to 100 free inodes in the superblock, called s_inode. Since the superblock is kept in memory during normal operation, this speeds up inode allocation (no need to search the inode array on disk to find a free one, as long as there are free inodes cached in the superblock). The number of valid entries is s_ninode, and when it reaches zero the V6 code simply re-scans the inode area to find 100 unallocated inodes. When repairing an unclean volume, we can avoid inconsistencies in inode allocation by just setting s_ninode to 0. As long as we have properly repaired the inodes and the IALLOC flags are all correct in the i_mode fields, the file system will just re-scan the inode area the next time it needs to allocate an inode.

Inodes

There is no change to the inode section. It's a giant array of inode structures, where the entry 0 of block INODE_START_SECTOR (2) of the file system corresponds to inode number 1.

Data Blocks

There is no change to this section of the file system.

Log Header

The log header is the first block of the log area of disk. Its contents are defined by the loghdr structure in logentry.hh:

struct loghdr {

uint32_t l_magic; // LOG_MAGIC_NUM

uint32_t l_hdrblock; // Block number containing loghdr structure

uint16_t l_logsize; // Total size (in blocks) of loghdr, freemap, and log area

uint16_t l_mapsize; // Number of blocks in freemap

uint32_t l_checkpoint; // Disk offset of log checkpoint

lsn_t l_sequence; // Expected LSN at checkpoint

uint32_t mapstart() const { return l_hdrblock + 1; }

uint32_t logstart() const { return mapstart() + l_mapsize; }

uint32_t logend() const { return logstart() + l_logsize; }

uint32_t logbytes() const {

return SECTOR_SIZE * (l_logsize - l_mapsize - 1);

}

};

The first two fields are sanity checks to ensure you really have a loghdr. The l_magic field contains the constant LOG_MAGIC_NUM (0x474c0636--a randomly-generated value), while l_hdrblock is the actual block number storing the loghdr structure. The first constant is unlikely to appear in random files, since it was randomly generated. The second constant ensures that if you copy a valid loghdr into a file, it still won't look like a valid loghdr since it will be at the wrong disk location.

l_logsize specifies how many blocks have been added to the V6 file system for the new feature set. This size includes sections 5--7 of the file system (the log header, freemap, and journal). With the new feature set enabled, the total number of 512-byte blocks of the disk image should now be s_fsize (from the superblock) plus l_logsize.

l_mapsize specifies how many blocks are used for the freemap. This must be large enough to contain at least 1 bit for each block number from the start of data blocks (at INODE_START_SECTOR+s_isize) to the end of the data blocks (at s_fsize).

Finally, l_checkpoint and l_sequence tell you where to start reading the log and what log sequence number to expect. l_checkpoint is the byte offset of the first log record you should read. (Because it's a byte offset, it should reside somewhere in the half-open interval [logstart()*SECTOR_SIZE, logend()*SECTOR_SIZE).) Each log entry has a consecutively-assigned 32-bit log sequence number or LSN of type lsn_t. l_sequence tells you the LSN of the first log record you should expect to read at offset l_checkpoint. If you see the wrong LSN, even if it appears to be a valid log record, you must stop processing the log as you may be looking at an old log entry.

Freemap (free-block bitmap)

The free-block bitmap has one bit for every block in section 4 of the file system (data blocks). If the bit is 1, the block is free. If the bit is 0, the block is in use.

The freemap is stored in V6Replay::freemap_. The freemap is compact enough to store the entire map in memory. It is read from disk for you in the constructor V6Replay::V6Replay, and written back to disk for you at the end of the V6Replay::replay method.

The freemap is implemented by the Bitmap structure defined in bitmap.hh, which is similar to a std::vector<bool>. Unlike std::vector<bool>, however, Bitmap offers a feature in which valid indices start at an arbitrary number. Since the first data block is INODE_START_SECTOR + s_isize (a.k.a. datastart()) rather than block zero, the first bit physically on disk in the freemap area corresponds to this "datastart" block. The Bitmap structure handles the translation because we construct it with a min_index. What this means in practice is that to mark block bn free, you just say freemap_.at(bn) = true; to mark it allocated, you say freemap_.at(bn) = false. Bitmap itself will do the work of translating bn to the appropriate bit.

If you have time, take a look through the implementation of Bitmap in bitmap.hh. It's interesting to see how the class allows you to address individual bits in the bitmap.

Log

The log consists of a series of log entries, each of which begins with a log-entry header, followed by a payload, and then a footer. Conceptually, the three fields look like this:

struct Header {

lsn_t sequence; // First copy of the LSN

uint8_t type; // What type this is (entry_type index)

} header;

entry_type payload;

struct Footer {

uint32_t checksum; // CRC-32 of header and payload

lsn_t sequence; // Another copy of the LSN

} footer;

Diagram by John Ousterhout

It's important to note that, while the beginning of the log will generally be valid, there isn't a clean end. The log just turns to garbage at some point after the last write, which might not even be for a full log record if the file system crashed.

To help identify the end of the log, the header contains a log sequence number, or LSN. This is a consecutively assigned counter that is unique for each log entry. LSNs are very important because the log area is repeatedly recycled. Hence, whatever bytes are left over from the last iteration may be old log entries or may look like valid log entries. These old entries must not be applied to the file system; doing so could actually damage the file system. Even a valid old entry might overwrite file data in a current file data block that was previously a directory or indirect block.

The header also contains a type integer, which specifies the type of log entry, and hence how to parse the payload. The payload section depends on type, and is one one of the structures defined in the main assignment spec. The payload immediately follows the type.

Finally, the log entry ends with a footer. The footer contains another copy of the sequence number. The second copy helps detect situations in which a log entry spans a sector boundary, and hence a seemingly valid entry could actually consist of the first half of a new log entry followed by the second half of an old one. There's still the possibility that the "right" log sequence number for the footer could appear in arbitrary payload data from an older log record. Hence, as an additional check, the footer also includes a checksum over the header and payload. The check reduces the probability of interpreting garbage as a log record by an additional factor of 2-32.

It's possible that the log wraps around and the next entry is put back at the beginning of the log area. (An alternative is always to write to the very last byte of the log before wrapping around, but this would result in log entries that are not contiguous on disk. Contiguous entries facilitate debugging: you can always start examining the log from the beginning of the log area and see some valid operations that happened, whether before or after the latest checkpoint.) To facilitate this, there is a log entry type LogRewind that indicates this has occurred.

FUSE

In addition to this updated (and backward compatible) design, the assignment also leverages FUSE (file system in userspace) to allow you to interact with a Unix v6 filesystem image as though it were a real filesystem on your computer. You can create an empty directory and run the provided mountv6 tool to mount a Unix v6 disk image in that folder. What this means is that while mountv6 is running, the root of the file system image will appear at this directory location, and you can traverse it, view/edit files, etc. as if it were a real filesystem on your computer. Pretty cool!

FUSE makes this possible - FUSE is a kernel feature allowing developers to implement file systems in ordinary user processes known as fuse drivers, without modifying the kernel. Normally, file systems are part of the operating system. But with FUSE, we can implement an operating system in user programs - when applications make file system calls, the kernel passes the system calls through as messages to the user-level fuse driver, which then passes the results back to the kernel. Though this architecture incurs a bit of performance overhead, it is used by production file systems such as NTFS-3G and the exFAT implementation commonly used on linux. The result is a fully functional file system that you can use just like the system's built-in file system to store files.

Creating Custom Disk Images

While not required on this assignment, the assignment tools allow you to create your own Journaling V6 file system images to play around with. To do this, use the ./mkfsv6 command and specify the name of the new empty image to create:

./mkfsv6 myimage.img

Then make an empty directory where you will mount it (any name works):

mkdir mnt

Finally, run ./mountv6 with the -j flag to mount the filesystem with journaling enabled. You can optionally include a CRASH_AT setting to cause the disk to crash abruptly at a certain block-write operation. For instance, to mount it but have it crash at the 1000th block-write operation, do the following:

CRASH_AT=1000 ./mountv6 -j myimage.img mnt &

Now you can interact with your filesystem within the mnt folder, including copying files in, moving files, editing files, etc. If your filesystem crashes, the terminal may struggle to navigate out of the mount directory, so you may need to cd to go back to your root directory and re-enter your assignment folder.

To terminate your filesystem cleanly and save all changes to the image, navigate out of your mount folder and run

fusermount -u mnt

The next time you re-mount this image, it will be in the same state you left it!

Another, more brutal, way to stop the file system is with

pkill -9 mountv6

This will kill the file system without giving it a chance to clean up, so the disk image may be inconsistent.

Lastly, if you have already written your apply program, if you would like

mountv6 to apply the log automatically when given the -j flag, you can uncomment the line flags |= V6FS::V6_REPLAY; in the main function of mountv6.cc. This will integrate the code you developed for your standalone apply program into the file system. Many journaling file systems automatically replay the log on mount with no need to run an external fsck program unless you had media failure or catastrophic software bugs. Integrating your replay code in the file system is optional, but a cool way to see your code in action!

Tools Reference

Here is a full list of tools included in this assignment's starter code. Not all are required to be used for this project, but they are cool ways to explore logging filesystems!

-

mkfsv6image-file [num-blocks [num-inodes [num-journalblocks]]] -- This tool creates a new file system. It uses the maximum size of 65,535 blocks (~32 MiB) and one inode per 2KiB by default, but you can specify different parameters if you prefer. By default it does not create a log area, expecting you to do this separately withmountv6 -j. However, you can specify a number of journal blocks, and it will create the journal area. If you specify 0, it will use a default size for the journal. -

dumplogimage-file [offset |c] -- Pretty-prints the log from the beginning, or from a specified numeric file offset. If you use the lettercinstead of a numeric offset, prints from the checkpoint. -

v6- A tool with various subcommands for examining the file system state. It expects your disk image to be calledv6.img. You can change this with theV6IMGenvironment variable (e.g.,V6IMG=test.img ./v6 ls /for a single invocation orexport V6IMG=test.imgfor all future invocations). Some useful subcommands:-

v6 dump-- look at the superblock and log header. -

v6 stat{path |#i-number}... -- shows the contents of particular inodes. You can specify inodes as pathnames or as#prefixed to the i-number. Be aware that#is a comment character for most shells, so you may need to quote it. (Example:./v6 stat /or./v6 stat '#1'to see the root directory inode.) -

v6 ls[-a] path... -- lists a file or directory in a format similar tols -alni. With the-aflag, shows time of last access instead of modification (similar tols -alniu). -

v6 catpath... -- look at the contents of a file. -

v6 iblockblock-number... -- dumps the contents of one or more indirect blocks, showing the non-zero block pointers. -

v6 blockblock-number ... -- dumps the raw contents of one or more file system blocks in a side-by-size hex and ASCII format with 16 bytes per line. This is convenient for directories because thedirentv6structure is exactly 16 bytes. (If you find this format generally useful, you can achieve something similar with the unix shell commandod --endian=big -t x4z -N 512 -jblock-numberb. However,v6 blockreplaces unprintable characters with space instead of dot, making it easier to identify the.and..entries in directories.) -

v6 usedblocks-- lists all allocated block numbers. If you are leaking blocks, this can help you identify which blocks you are failing to mark free. -

v6 usedinodes-- likeusedblocks, but lists all allocated inodes. Useful if you are leaking inodes.

-

-

fsckv6[-y] image-file - Reports what's wrong with the file system. If you use the-yflag, it will bring the file system back to a consistent state. However, it doesn't have any support for logging and will disable the log. (You can always recreate the log by supplying the-jflag tomountv6.)